The Metal Art of Robert Ebendorf

11 Minute Read

Crushed tin foil, marred tintypes, rusted cans—some must have thought it looked like garbage. In 1967, this detritus of our collective consumption found its way onto the walls of the Art Gallery of the University of Georgia. The artist responsible for this conglomeration was Robert Ebendorf, then Assistant Professor of Art, who mounted 10 assemblages for his first one-person show.

However, this work was hardly "off-the-wall" in the art community or even in the jewelry community, to which Ebendorf belonged. Here, questions concerning the nature of the medium and the viability of alternative concepts and materials were beginning to be asked on both sides of the Atlantic. And although Ebendorf received his training both in the United States and abroad in highly disciplined metalsmithing skills, his bold wall works of recycled metal marked an irreversible escape both physically and psychologically, from his traditional roots.

Ebendorf's work has found its core in contradiction—in a dialogue between tradition and change which he has gone on to embroider and embellish, and, ultimately, to use to influence two generations of American metalsmiths. Ebendorf is both a product of his training and of his age—he was among the first links in a long transitional chain of jewelers who challenged and then redefined jewelry for a new age and a new culture.

In contrast to the artist investigating a particular esthetic notion, or evolving a private code or visual language which serves him as a means to probe formal concerns, Ebendorf used the choices he made in his art as both the subject and object of his esthetic investigation. The dialogue may alternate between internal and external, but it is never allowed to stop.

While this approach has opened his work up to being criticized as hodge-podge or the "kitchen-sink-school-of-jewelry," as one peer called it, diversity can be seen as both its unifying element and is esthetic strength. Ebendorf's work has a manic, jumpy, frenetic energy of something evolving "as we speak." The vitality present in the best of Ebendorf's work is a result of the immediacy of this quest—a search that itself became his methodology. Thus, the work provides a record of the struggle of that inquiry, as he continuously ask, "what more? what else?" his art might be.

And he is not uncomfortable asking it of himself or anyone else who might be in earshot. Posing probing questions to himself and his peers transforms the process into an ongoing conversation. The rich range of elements that he allowed to enter this dialogue make up is working vocabulary. The defiant act of 1967, against the homogeneity of the Scandinavian Modern esthetic in which he was trained, may be seen as the opening argument to a career of tireless debate.

Ebendorf relies on visual and verbal interchange to accumulate and reorganize the information that flows through his mind and his work. Through his example, the clarity of the artmaking process as a way of storing, ordering and reprocessing information becomes dramatically focused. Where one aspect of Ebendorf's development was inadvertently hampered, his intelligence prevailed, providing him with the means to harness his esthetic inclination and devise a highly sensitive and creative system to interact with the abstract and often abstruse world.

The seemingly disjunctive nature of Ebendorf's creative development, then, is really a very controlled and deliberate investigation, which found its first embodiment in the cumulative detritus of the 60s work and was later to be couched within the process of collage. The term collage in art has been variously seen as the combination of elements belonging to separate intellectual or perceptual categories, as a shift in perception of objects beyond their familiar representation and as impersonal workings of pictorial form as rhetorical devices.

With collage providing the important investigative syntax, there are several threads of intention and motif that weave through the body of Ebendorf's work. One that recurs is that of the artist as correspondent, an almost obsessive need that derives not only from the artist's own struggle with mastering the written word (due to dyslexia), but also from his reaction to the omnipresence of the written word in our culture. Ebendorf's private conversations often take the spontaneous form of mail art, where metallic confetti or crayon scribbles in a child's hand (often collaborations with his three-year-old daughter) tumble out of a hastily scrawled envelope. The letters themselves are exciting pastiches of Xeroxed images or line drawings, mixed with oddly placed boxes filled with half-printed, half-cursive hand, full of misspellings and malapropisms. The time spent in deciphering is time spent with the excited thoughts of the artist, thoughts that convey a meaning beyond the content of the words and that, like his collages, draw the recipient into his personal world.

In his work, Ebendorf's first breakthrough was the shedding of the idea of raising form, the three-dimensional manifestation of metal in holloware, so important to the Scandinavian Modern esthetic of his training. Instead, as seen in the 1967 wall assemblages, his work has been overwhelmingly flat, organized to be "read" as if it was a printed page. His predominantly rectilinear formats are covered with layers and multiplicities of material, like the texture of an illuminated manuscript. To further the analogy, Ebendorf frequently uses paper in his amalgams, from old journal pages to gold foil to Oriental newsprint.

Pop Art was a great releasing mechanism, not only for painters and sculptors but also for metalsmiths like Fred Woell, Ramona Solberg and Ken Cory. The recycled, collaged sensibility of Pop also appealed to Ebendorf, who combined old tintype photos, metal scraps and found metal relics with cold connections to fashion his discourse. At the time, it seemed that this collaging had more to do with the sociopolitical climate of the day than with a truly personal statement about the meaning of these objects. On the other hand, the impulse to decorate, to personalize through surface embellishment, was also a strong draw for the energetic artist. Ebendorf turned out many pieces with repetitious, scribing notations, weaving together these seemingly disparate images and materials to form the substance of his visual texts. It is as if these markings, these personal gestures, etched into the anonymous and unrelated fragments, provided the transformational ingredient to turn junk into jewel. Most often this embellishment is an organic scrolling of repeated forms that makes a delicate tracery on a section of a metal "page."

It was in his Portable Souls series of the late 60s that Ebendorf took the "page" metaphor one step further. In this series, he totally refit and reprogrammed worn, prefabricated daguerreotype cases. Hinged at the spine, these leather bindings containing his esthetic jottings seem more like diminutive books. For their secret, their soul, is found on the interior. It is inside that Ebendorf uses his personal handwriting to unite an unlikely juxtaposition of found Christian icons, jewels and recycled bits. Evocative of private altars, the embellished surfaces themselves are reminiscent of the gem-encrusted covers that protected priceless Byzantine manuscripts.

The fascination and involvement with dialogue is explored in the 1973-74 series called Colored Smoke Machines. During this time, Ebendorf began building a close relationship with Claus Bury. It was this German jewelry artist who introduced him to the European practice of exhibiting working drawings beside finished pieces. This had enormous appeal to Ebendorf, who wanted to give his viewers as much information about his thought process as possible, to develop a rich dialogue. He momentarily left his flat arena in favor of impeccably crafted, constructed or hammered enclosures of gold and silver, plexiglass tubing, bonded acrylic sheets and pearls. But he refused to abandon the page. He began incorporating a large, elaborately finished "working drawing" into many of these presentations, placing the finished piece judiciously atop the drawing as the three-dimensional conclusion to its backdrop. He played extensively with these sheets, sometimes suggesting they were an architectural plan and elevation, and with others going to great lengths to collage bits of drawings as though done at different points in time. They are finely rendered blueprints for the viewer and a means for the artist to reach out and directly speak to his audience.

Some of the most successful assemblages that Ebendorf created were done for an exhibition at the Heller Gallery in New York in 1982. The diversity of his experiments - flat, graphic presentation; nonprecious jewels; constructed containers; illusion, transformation; dialogue—were orchestrated into serial compositions of poetic clarity. One powerful metaphoric refrain was once again of the artist as scribe.

The heart of this collection was a series of two-inch-square brooches, many of which were presented as collage/paintings. This effect derived from the closure provided by a mitered wood frame. A diverse array of materials, including mother-of-pearl, Formica, gold foil, wood marquetry strips and colored and engraved papers were worked into the frequently violated framed format. For many of the pieces, an intricate, trompe-l'oeil photographic tableau was created with collaborator Francois Deschamps. The multiple layering of texture and image gained by means of the photograph formed a vibrant backdrop for the theatrical presentation of the brooch. This conceptual play of dimensionality and illusion formed an internal dialogue within the piece that was quintessential Ebendorf. For, as the viewer explored the imagery, it became clear that the "jewel" itself was faux, just a "semi-precious" bauble, that from a distance had seemed to shimmer. Yet even with all this visual trickery, the theme of this work leads back to the book, this time a child's pop-up album that itself plays on the confusion of three-dimensional versus two-dimensional space.

The numerous references to the written medium in this group make a cohesive statement. Most dominant is the repeated inclusion of a series of anonymous pages from an aged and yellowed journal. A large and flowing cursive script, produced with a fountain nib, graces the blue-lined sheets in faded sepia ink. Ebendorf no longer remembers from where the notebook comes, but a powerful romantic presence attaches to this old testimony of a once-sure hand. Torn from is binding and used unaltered, a leaf becomes an explanatory page. In truth, its words have nothing to do with the "pictures." Or, carefully sliced and reassembled as a brooch/collage component, the pen marks are made totally gestural and rendered illegible. Either way, these random pages allow the artist to take charge of the words and manipulate them in a way he is free to do nowhere else.

Other references to the power of the written page in this collection are equally compelling. Many of the square brooches have their frames visually broken by a thin, diagonally placed form, intruding from a lower corner. Sometimes pointed, it has the effect of a writing implement poised over a page. In one large tableau, a well-sharpened pencil hovers over the gridded leaf of a contemporary notebook. Ironically, it is painted white, rendering this communication tool as mute as a George Segal figure.

Throughout his prolific career, Ebendorf has sought the challenge of collaboration with peers Jamie Bennett, Ivy Ross, Richard Mafong, Bruce Baker and photographers Jerry Uelsman and Francois Deschamps. In each case, collaboration becomes the most effective way for Ebendorf to "converse" with artists he greatly respects. Collaboration short circuits the difficulties that would arise by attempting only to verbally communicate abstract ideas about the nature of art and vision. In place of such verbal or written exchanges, he thrives on the immediacy of shared action. Collaboration offers a means of gaining "hands-on" knowledge of the work of peers and offers both collaborators the chance to engage in what is, finally, most important—an ongoing dialogue.

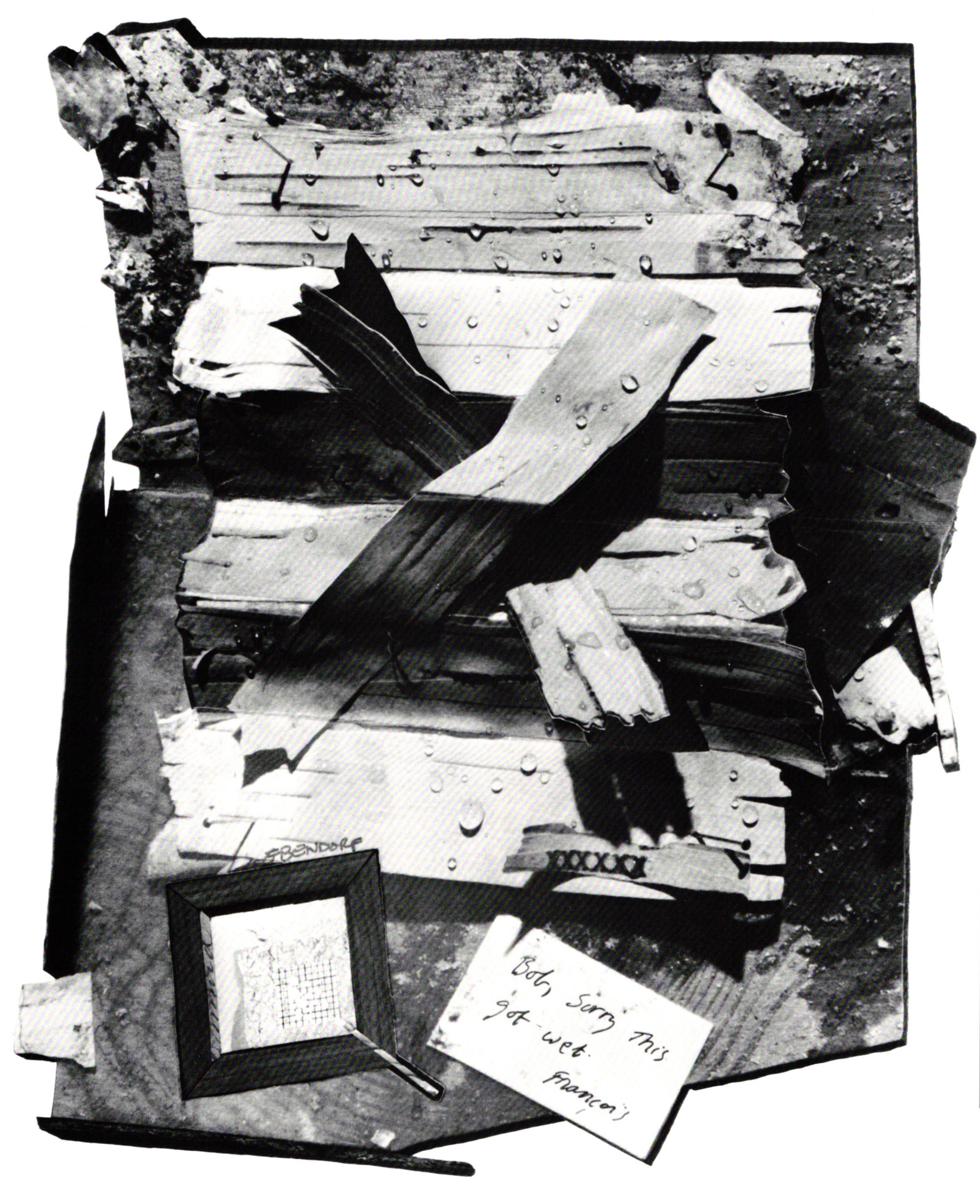

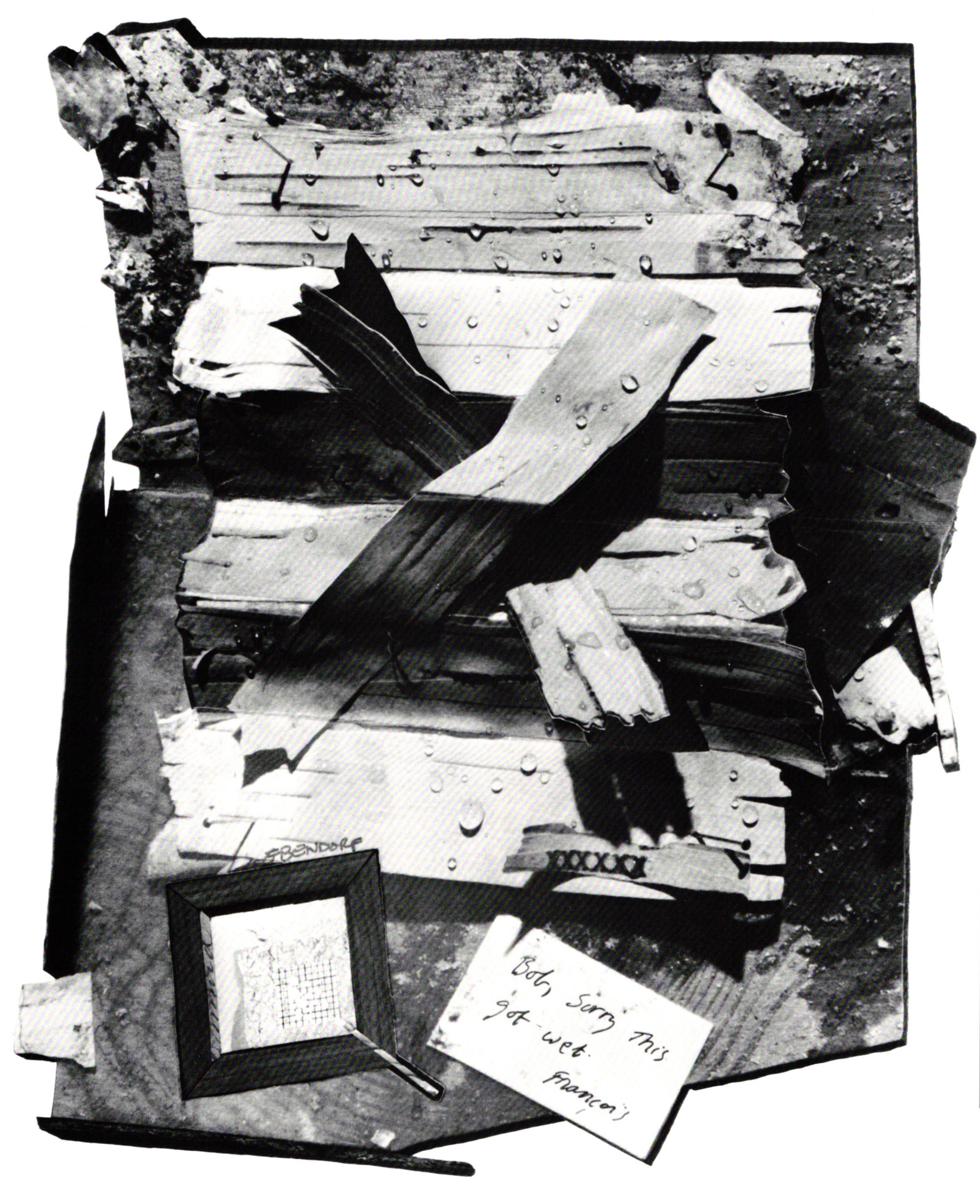

This point is rendered with humorous clarity by one of the 1982 collaborations with Deschamps. A trompe-l'oeil collage simulating richly textured shavings of wood and paper appears to tumble toward the viewer. Startlingly realistic beads of water shimmer on the faux surfaces. At the lower right edge of this photographic composition is a white card on which the photographer cunningly leaves a handwritten note for his friend, "Bob, sorry this got wet. Francois." Here, the communication, so critical to the process and the product, has wittily been acknowledged and incorporated into the final piece.

Often, it is the most elusive talents or skills that become the most relentless taskmasters. The drive to overcome provides the impetus for unprecedented accomplishment. Robert Ebendorf was given the soul of a poet, but the words didn't come. Undaunted, he took his considerable gifts and developed a means to speak eloquently through the art-making process. Claiming his own structure and vocabulary, he fashioned a richly tactile means of ordering a world of fragments into a poetry uniquely his own.

See Rosalind E. Krauss, "In the Name of Picasso," in her The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), p. 38.

A retrospective exhibition of the work of Robert Ebendorf was held from April 4-26 at the College Art Gallery, State University of New York, The College at New Paltz. It will travel to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI in the summer of 1989. An 80-page color catalog with essay by Vanessa Lynn is available from: Robert Ebendorf, RR1, Box 187x, Highland, NY 12528 for $25, including shipping.

Vanessa S. Lynn is a writer living in New York, who frequently contributes to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Jewelry of Patsy Croft

Betty Helen Longhi Exhibition

Erik Stewart – Inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge

The Invisible Setting Process

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.