Metalsmith ’85 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

39 Minute Read

This article showcases the various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1985 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Image as Metaphor

Beaver College, Glenside, PA

March 29-30, 1985

by Dana Standish

Sponsored by the Pennsylvania Society of Goldsmiths, with the support of the metals departments of Beaver College, Philadelphia College of Art, Moore College of Art, Tyler School of Art and Millersville State University, the "Image as Metaphor" symposium featured the works of artist/metalsmiths Harriete Estel Berman, J. Fred Woell and Bruce Metcalf. The symposium centered on an exhibit of the three artists' work, complemented by a day-long slide presentation and panel discussion during which the artists were asked questions pertaining to the sources and meanings of the metaphors each of them use in their very personal imagery.

Harriete Estel Berman is a West Coast artist whose work is titled collectively The Family of Appliances You Can Believe In. Berman makes meticulously created household appliances that are designed to show the allure of consumerism while at the same time making sardonic references to women's role in modern society. Many of her references seem obscure enough as to be a sort of "in" joke, but most of her works are so filled with images that they are bound to make an impact on one level or another. Idols of Generations, Illusions to Prophesy (1983) is a work whose perhaps unnecessarily obscure title does much to undermine the directness of the imagery. The piece is a common, household "Never Lift" steam iron, about one-third life size. However, the front surface of this "normal" steam iron opens to reveal the repousséd faces of many women and girls, all shielding the bottom half of their faces with large flat discs (dinner plates?). Holding these discs are hands cut out of Ivory Soap magazine ads. The women are anonymous, covering up most of their faces. But Berman's message is clear: women are trapped by housework and trapped by advertising into thinking that modern appliances will somehow make life easier.

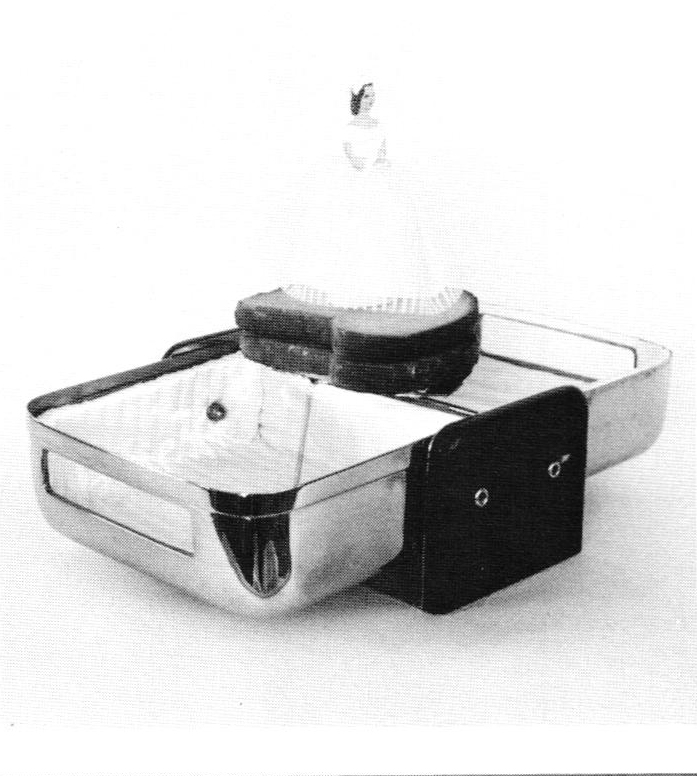

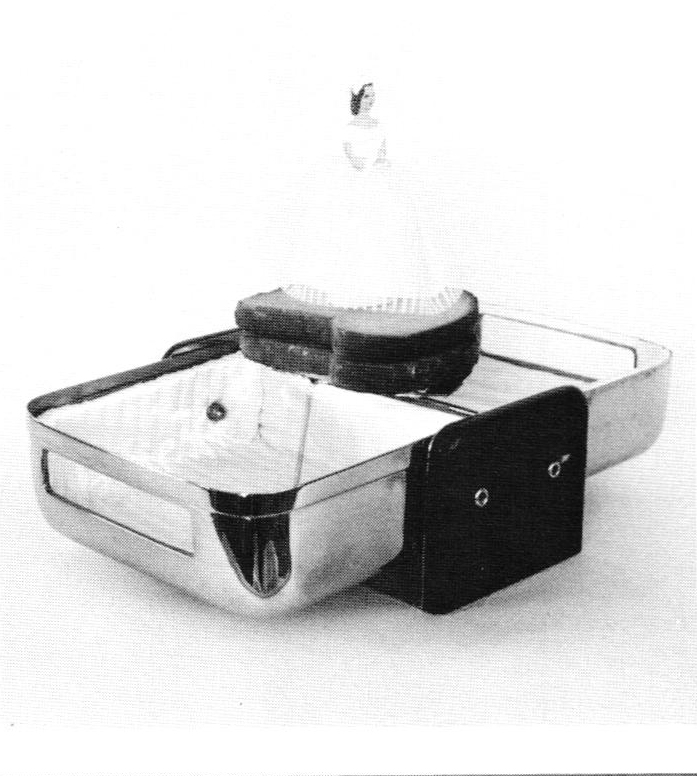

Other Berman pieces are equally sardonic if more humorous about "women's place." Toast to the Bide shows a shiny new toaster that opens to reveal a bride doll on resin-saturated slices of Wonder Bread rising out of her quilted toaster-coffin. Eveready Working Woman is an electric drill-cum-egg beater, which also includes a compartment with six shades of eye shadow and one with a lipstick, as well as a blow dryer, all the necessities for the woman who really wants to compete in a man's world.

J. Fred Woell's images are equally as direct, if on a different theme. Woell's theme is that of aging: specifically the feelings of the male at mid-life. The images in this show were as pointed as previous Woell works, but this time they seem to be pointed inward. Instead of at society. The Male Mid-Life One-Step is a cast likeness of a man stepping blithely, full-speed-ahead, hat over his heart, off the end of a trivet and into the Great Unknown. The trivet is of standard-issue 50s household variety, inscribed "Good Luck," which is just what this hapless fellow is going to need as he moves into late middle age.

Boy Scout Gets Old is another Woell piece on this same subject. It is a wooden music box with a cast boy scout standing at attention on top of what appears to be a two-tiered wedding cake. The boy scout holds the mask of an old man in front of his lace. As the music box plays, a small sports car turns inexorably around and around.

Both Berman and Woell have found ways to translate their artistic metaphors into images that are accessible to the viewer. Bruce Metcalf, the third member of this show, seems to have an equally strong sense of purpose in his work, but his images are so muddled and self-conscious as to render any question of metaphor moot. If the viewer cannot grasp the meaning of the metaphor, meaning may as well not be there at all. And so his works must be seen merely in terms of design and craftsmanship. This surely puts Metcalf out of his league in a show titled "Image as Metaphor" with images as clear as those of Berman and Woell.

Metcalf's preoccupation seems to be with exorcising the frustrations he feels about life. To this end he has constructed a huge tower of metal joined helter-skelter, titled Got an Ulcer. This piece, with its lagged, violent forms, is more likely to cause an ulcer than it is to convey what he felt like when he "got an ulcer." Other works, like Natchos and Net and Two Figures Breaking Away, are conglomerations of jagged forms, some being torn limb from limb, decorated with wild zigzag shapes and twisted wire. Many of his works are plopped on enormous pieces of plexiglass that have been splattered for some reason with purple paint. Metcalf achieves a sort of wild tension in his works—partly because of the violence of his imagery and partly because this violence is contrasted with the fact that he really is a very fine craftsman. He has a showy way of arranging shapes, but he doesn't appear to have much to say. Many of his solutions are too pat and depend too much on the viewer's gullibility in being convinced that if there's this much smoke. there must be at least some fire.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Metalwork '85

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

February 3-26, 1985

Holtzman Art Gallery, Towson, MD

March 15-April 12, 1985

by Joke van Ommen

This was the third exhibition organized by the Washington Guild of Goldsmiths to show the work of its members. Curated by New York jewelry designer Glenda Arentzen and Renwick Gallery curator Michael Monroe, the exhibit included 93 pieces by 43 metalsmiths, most of whom work in jewelry.

Part of the success of the WGG as an organization is its democratic structure and openness: There are no membership requirements; anyone working in metal or interested in jewelry may join. The guild's purpose is educational and informative. Its strength lies in the happy cooperation and exchange of ideas, both technical and artistic, within this varied group. Because of this openness, a membership show reflects a wide diversity in style and technical perfection. Work of relative newcomers to the field can be seen next to that of accomplished international artists. To review the show as a whole is, therefore, quite impossible. Instead I will concentrate on developments in style that I observed in comparing this show with the guild's last one, held in 1982, and discuss a few of the pieces that illustrate these developments.

In the past three years a shift seems to be noticeable, from an emphasis on ornamentation and intricate designs towards a more structural and architectural approach in jewelry design. In general, the forms are simpler, paying less attention to beautifying, with its inherent danger of overloading a piece and losing one's self in details. We see, therefore, stronger statements, more mature and deliberate designs. One could also see that the workshops organized by the guild in the past three years were reflected in the pieces presented in the show, and this technical knowledge was used by the individual jewelers in many interesting and personal ways.

Of note in the show were the following: Lisa Vershbow's bracelet, conceived as an entity and equally interesting from all sides, had a strong sculptural quality. The contrast between the matt and shiny surfaces made the highly polished diagonals seem to protrude more strongly. In Christine Thrower's pin the simple lines of the metal were beautifully integrated and matched with the shape of the centrally set stone. In concept and execution the pin was a unity. Janet Peters' pin was more complex. Because she restricted the lines to a few angles, there was a logic and balance in design and composition. The color was strong: the blue of the lapis lazuli combined perfectly with the niobium blues. Tina Chisena gave her pin movement and force through aggressive repetition of lines and sharp angles.

Some other examples of the many beautiful pieces on display were: Judy Frosh's pendant Kyoto's Forbidden Gate—subtle mystery and beautiful use of several oriental techniques. Yvonne Arritt's collar Space Wing N—very strong and clean in design. Although the piece was bold in shape and size, it suited the human body very well. Wilma Lehman's pin Puffin—flowing lines reminiscent of Art Nouveau. The same Art Nouveau inspiration was found in Betty Helen Longhi's Necklace/Sculpture, where the two separate parts seen together formed a sculpture in one flowing line. When the necklace is removed, the remaining form holds its own.

This show was an ambitious undertaking for an organization that must rely totally on volunteer labor, and its success is a tribute to the guild's vitality.

A 20-page black-and-white catalog documenting one piece by each of the 43 exhibitors, is available for $2 from: Washington Guild of Goldsmiths, 8532 West Howell Street, Bethesda , MD 20817.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

David Freda/Stephen Walker

Contemporary Metalsmiths Gallery, Chapel Hill, NC

October 26 November 17, 1984

by Jane Kessler

Though technical wizardry is a common bond between the two artists in this exhibit, the objects were nearly antithetical, both visually and philosophically Stephen Walker works in the tradition of object-making object for object's sake. His allegiance is to the seductiveness of the metal, to form, to visual enticement. His bowls, goblets and other functional objects in this show were primarily of married metals.

His interest in tesselation, defined by Walker as "a shape such as a checkerboard square or a honeycomb hexagon that, where repeated, covers a continuous surface," has presented extraordinary technical challenge. Some of the earlier pieces in this exhibition show evidence of Walker's technical battles, with less than smooth joining of the metals detracting from what should by nature of intent be a nearly perfect form. His later, more masterfully resolved bowl forms are begun as a soccer ball shape that is raised to a smooth sphere. In these he establishes an ambiguous visual pattern wherein background and foreground vie for dominance. Backs and fronts, insides and outsides of the vessels and platters are similarly competitive. His sense of and love for strong geometric patterns is rooted in a lifelong interest in Celtic art, and he uses some of these ancient patterns and symbols as sources. Since Walker's sources are often historical and symbolic, content must lie somewhere beneath the surface of these opulent works. Its significance to his audience, however, is Negligible. These works are to be marveled at as beautiful objects.

For Freda, the metal is more a means to an end, its natural qualities often obscured. In direct contrast to Walker, Freda's work is pictorial and literal and he places integrity of object below integrity of statement or subject. Freda is obsessed by nature, reverent of it and critical of man's common irreverence for it. His love for the snakes, toads and creatures that he so faithfully depicts often infuses the work with an unfortunate preciosity. Several of Freda's pieces in this exhibition were mason jars with his exacting replicas of captured inhabitants convincingly clinging to sticks or wire mesh. Freda brings these works back around to jewelry by making the toads, lizards and other natural objects function as pins or neckpieces. As jewelry, the works are very successful but once again distract us from what I believe to be Freda's prime purpose, which is more evident in pieces such as Crack of Bizarre Delights, where a delicate hummingbird is caught in a deathly gauze. This comes closer to stating Freda's concerns about the fragility of life forms beyond humans and their dependence on our sensitivity to them.

Guardian, the most awesome of Freda's pieces, is, in function, a jewelry box. An exquisite snake guards the geometric box containing her eggs, which Freda has made of silver and finished in a pearlescent white surface. The combination of beauty and threat make this ambitious work very powerful. Within this collection of works, Freda seems clearly to ask that we look beyond the object and the metal, whereas Walker asks us to appreciate craft and the inherent beauty of the material.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Great West Metal Show and Symposium

Northern Arizona University Art Gallery, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ

February 20 March 15, 1985

by Betsy Douglas

For the past four years The Great West Metal Show and Symposium has been held annually at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona Hosted by Joe Cornett, head of the Jewelry/Metalsmithing Department at N.A.U., this special event has averaged each year over 100 participants from the United States and Canada. Distinguished artists invited to past shows and symposia, have included Lynda Watson-Abbott, Harlan Butt, Lane Coulter, Michael Croft, Bob Ebendorf, Mary Lee Hu, Irene Mori, Eleanor Moty, Gary Noffke, David Pimentel, Gene Pijanowski, Heikki Seppä, Helen Shirk, Don Williams, Kay Yee and Sandra Zilker. The 1985 event featured Hans Appenzeller, Arline Fisch, Christine Smith, Jay Burnham-Kidwell and Peter Jagoda in an exhibition, slide lectures and a workshop. The exhibition evidenced a broad range of individual statements including jewelry, objects and knives.

The elegant work of Hans Appenzeller of Holland, shown in an overview of the years 1973-1984 in 28 pieces, contributed his international approach to jewelry design. Appenzeller's designs reveal the Dutch desire that jewelry emphasize concept. Appenzeller works in series or collections, each investigating a particular theme, problem or special material. Two bracelets from the 1973 collection featured aluminum tubing and rubber straps to make the closing at the wrist or to act as a hinge to join the two part band. Four bracelets from 1981 combined marblelike synthetic discs of corian inlaid with black pvc strands, some of which extended like black tentacles that bounce and bend when worn. A large, handsome cuff of women stainless steel exemplified Appenzeller's interest in textiles and principals of industrial design and engineering. More organic in character were the 1984 structured cuffs and woven matt earrings, cast in precious metals from filed woven strands of wax. These recent works continue Appenzeller's design sensitivity in creating elegant jewelry, dramatic when worn.

Arline Fisch also explores the use of textile techniques in metal to create bold, dramatic wearable forms. Her necklace brooch of platinum and 18k gold, entitled Woven View, incorporated a skillfully woven neckband accented with a detachable chevron-shaped woven brooch with gold and platinum triangles. Of particular interest were new works by Fisch in which she combined stainless steel mesh with gold leaf and precious metals. A large, triangular pendant Steel and Silver #4 featured layered mesh and gold leaf combined with a silver triangle that had been subtly roller printed with the mesh texture and hung from a 14k gold neckring. The layers of mesh created a moiré pattern that gave an illusion of depth. The gold leaf glued into the mesh added a subtle color accent and a rich painterly quality to the work. Equally striking was Double Brooch, a metal collage of mesh, gold leaf, fire-gilding and silver, inlaid with nickel and copper. Fisch's 14 works demonstrated her continued interest in the wearability of jewelry and her desire to stretch the limits of what people will wear.

A contrasting approach was projected in the metalwork by Christine Smith. Not concerned with wearability, she uses the brooch format to create impeccably crafted, colorful and often humorous comments on her experiences and places she has lived. An especially cold winter produced Frostbites, a miniature window with shade set against a fragmented wall of silver pierced with tear-drop-shaped patterns. Outside this tiny environment were three colorful "frostbites" of turquoise, coral and purple acrylic. Mounted on tiny stands, they had rectangular heads with eyes and open mouths full of sharp teeth.

Humor was also evident in Window Grille by Jay Burnham-Kidwell. Made of forged steel and titanium, this 5′ by 2′ construction included images of a palm tree and flamingos. Kidwell is skillful in his forging, chiseling and joining. Characterized by classic simplicity was Kidwell's Sardines Bowl, a 12″ vessel of raised mild steel with a tiny chased sardine near the edge.

Peter Jagoda's recent works demonstrate his skill as a knifemaker. His graceful 4″ Thumblade and whimsical 3″ Thumblade were made of 01 steel and brass with handles of white micarta in which he has inlaid tiny shapes, dots and dashes of colored epoxy. Jagoda's knife forms were sensitively shaped and often detailed with grooved file work as an individual accent. Good examples were his handsome Drop Point Skinners with black micarta inlaid epoxy handles. Jagoda's knives are works of art that succeed functionally as well.

As in the past, this year's successful Great West Metal Show and Symposium enabled the enthusiastic participants to view a large body of well displayed jewelry and metalwork by each of the talented invited artists. Of particular value was the opportunity to hear the artists talk about their development. Fisch's hands-on workshop introduced various weaving techniques in metal. The slide lectures and informal discussions enabled students and professionals to share a stimulating and productive exchange of ideas and technical information. Allocades to Joe Cornett for his important contribution to the growing field of metal arts by continuing to host the Great West Metal Show and Symposium.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Learning and Earning

Jewelry Students Co-op, Kent State University, Kent, OH

Spring, 1985

by Bruce Metcalf

Every semester, the Jewelry Students Co-op at Kent State University sponsors a five-day jewelry sale I organized the first sale in 1981 when I carne to teach at Kent State. and it has since become an ongoing tradition Advanced students are typically given assignments related to production techniques before the sale takes place. Second-semester students learn rubber mold-making and wax injection and are asked to make half-a-dozen pieces. On one occasion, the advanced class was divided into groups, who worked collaboratively on designing and producing a line of jewelry. But most often, students work on their own Pieces, using their own priorities.

As in any grouping of jewelry, earrings and rings seem to sell best. Students also produce pins, bracelets, pendants and neckpieces. Prices are most often below $5, but sterling earrings and rings sell quite well above $15 Most students use the sale as an opportunity to let go and have fun, using all sorts of found materials in a collage oriented approach. Local hobby stores and hardware stores contribute much of the raw material for this.

Each piece must be mounted on a square of cardboard, or in a plastic bag, because all the work is presented on large pegboard panels. As a result, many students make a coordinated presentation of the jewelry and its packaging. Others use the opportunity to make exotic juxtapositions: a fashion design major made earrings of inner-tube rubber packaged in clear plastic disposable gloves; another student placed colored-Xerox pins in ziplok plastic bags.

The sale nets; about $1500 in five days, 15% of which is donated to the Jewelry Studio and 10% is paid to the organizers of the sale. A coordinator is elected by the advanced class each semester, and he or she takes care of reserving space, inventories, advertising and setting up monitor schedules. It's a fairly involved job, and the 10% commission is a fair compensation for so much work.

The Jewelry Sale turns out to be educationally rewarding as well as profitable. During the week of the sale, most students are madly producing new pieces to replace depleted inventories, and a sense of shared goals emerges in the class. This cohesiveness helps motivate people year-round. Students also get a taste of the business aspect of jewelry making: the necessity for working rapidly and efficiently, the difficulties of deciding on a retail price and the desirability of accommodating public taste in order to sell a volume of work. Those students who are interested in becoming production jewelers use the sale as a low-risk environment in which to test new designs and techniques. Other students, less interested in economics, use the sale to experiment with fresh and energetic approaches to their work. Everybody learns something and everybody benefits.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Two Sensibilities

Art Department Gallery, Montgomery College, Rockville, MD

January 20-February 8, 1985

by Fred Fenster

This exhibition marked an unusual juxtaposition of different styles and attitudes. While both artists had studied with Stanley Lechtzin at Tyler in Philadelphia, Yoo now teaches metals at the university in Seoul, Korea and Metcalf teaches in the art department at Kent State in Ohio.

The impressive array of work was strong in content and individuality. Yoo's pieces have softly flowing, gentle lines with subtle inlays and combinations of sterling, copper and nickel silver. Though smaller in scale than Metcalf's, they have a feeling of quiet power and timelessness. They glow with a soft, lustrous quality.

Both artists work with a great deal of emotional content, but Metcalf's pieces seem cathartic. Pointy, jagged elements float on thin rods and move restlessly in space. The surface of much of the metal is painted, and there is a sense of whimsy and humor in the treatment of form and surface.

The exhibition was beautifully mounted, enabling one to experience the quiet power of Yoo's work and explore the sense of play and adventure in Metcalf's. It was a fine example of the mature expressiveness of the two artists.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Martha Glenny: Souvenirs — le souvenir

Anna Leonowens Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia

November 6 - 10, 1984

by Joanne Poirier and Paul Leathers

"Souvenirs le souvenir" was a collection of 11 pieces dealing with a dichotomy in the interpretation of the word souvenir. Martha Glenny states, "There is a subtle, but quite distinct difference between the English and French definitions . . . of the word souvenir. This body of work plays with this difference of meaning and it suggests alternative sources for souvenir imagery." This duality exists within each piece and is reinforced by the presentation in the gallery, "The poverty of conventional souvenir imagery lies in its failure to express anything about the nature of the thing or place it depicts beyond the superficial."

Glenny's personal relationship with the Niagra area provides her with a source of alternate souvenir imagery, which is juxtaposed with a conventional souvenir format. The decal, shield and pennant shapes function as a point of reference for the viewer.

In Rainbow Decal Pin a photograph of the falls is overlayed, by means of a transparency, with a hand-drawn rainbow. Here we see a physical reality embellished by the artist's intent presented together with a traditional souvenir.

The two pennant forms challenge our definition of jewellery. Are these hand-held objects to be considered jewelry? Despite having no conventional means of attachment, these pieces are nonetheless body referential and therefore function within the criteria of personal adornment. The imagery for these two pieces draws on Glenny's interest in the geological history of the site and conveys "something of the physical reality of, what is after all, an extraordinary natural phenomena." In this way Glenny offers a facet rarely seen by the casual observer.

In Topographical Map Badge the artist plays on the duality between the cartoonlike imagery of the map and the physical reality it signifies. The two-dimensional graphics are bisected and made three dimensional and reference is made to inherent structural qualities.

One might well ask whether these pieces continue to be successful when removed from the context of the exhibition. Seen in conjunction with their visual sources, they project a stong and coherent presence. Outside of the gallery, they remain fragments of a larger whole — each a souvenir of the event. Glenny's work should be viewed from the standpoint of being an installation piece. This was not a jewelry show but rather a show of work by a jeweler. While all the pieces were wearable, they dealt more with jewellery as art than with jewelry as precious object. This collection of work illustrated a new and exciting direction in Glenny's development as an artist.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Betsy Douglas: MFA Thesis Exhibition

Harry Wood Art Gallery, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ

October 15-19, 1984

by Anne Krohn Graham

Does our environment really have an impact on what we produce? If it does, then Betsy Douglas must find it comfortable working in the Southwest. Her work seems to echo the sensual forms of the mountains, which appear to fold in and out of the earth. Or perhaps she is inspired by the curves of the human body itself. One of her strongest works was an earpiece designed to cover the entire ear and which complimented the natural folds of the ear.

The same care, consideration and craftsmanship is to be seen on all surfaces of the pieces. She gives special attention to detail, such as how the pieces are terminated. Contrast in her pieces derives not from patina but from a subtle variation of white texture given the silver through scratchbrushing and hand polishing. Douglas's work displays a sensitivity to angles, curves and proportion, as well as; an awareness of how the pieces will be worn on the body. For this show, the culmination of her MFA degree from Arizona State University, she executed both wearable pieces and functional objects, including neckpieces and collars, bracelets, ear ornaments, rings and a pair of candlesticks. Although she involved herself with many techniques during her last five years at A.S.U., here she chose to focus on folding thin-gauge sterling silver to create a volume of form.

The quality of the work was matched by the originality of presentation. Douglas's professional background as a graphic artist and theatrical set designer contributed to her unique presentation of her work on opening night. A dance performance by the Desert Dance Theatre Troup of Phoenix gave the audience a dramatic introduction to the pieces. Each of four stylized mannequins was draped differently in teal blue fabric, representing four different ethnic looks. These soft black mannequins became the stage setting for the dance troup to adorn these figures with pieces of jewelry. The dancers, who were themselves dressed like mannequins, echoed the undulating flow of the folded metal pieces as they performed their interpretive modern dance. The choice of dance presentation added to the consistency of the show, as the dance movements and the metal movements complimented each other. The dancers were able to move with ease, indicating the comfort of the jewelry on the body.

In addition to the 16 pieces on display, the artist arranged for 10 other pieces to be worn by guests on opening night. These pieces were Douglas's constructed landscape series from which the folded forms evolved.

Although the previous series was done with integrity, the new work is more naturally flowing Douglas has emphasized the crispness of the metal along with its sensuous qualities. She has chosen lightweight gauges to express this larger scale jewelry. The boldness of form carried well, although intrigue was created by her attention to detail. The work had a dramatic elegance, with concern for proportion.

Betsy Douglas has made reference to inspiration received from past and present Mary Ann Scherr, Eleanor Moty, Mary Lee Hu and David Pimentel. However, her work has a distinctive singularity that comes both from maturity and feeling comfortable with materials. Her achievements can set an example for anyone working for this professional degree.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Kristin Moore Retrospective

Artwear, New York City

March 7 16, 1985

by Vanessa Lynn

The word "retrospective" always sends a tingle of anticipation down the spine. For, at the very least, the viewing of an expansive, historical cross-section of an artist's oeuvre promises new insights into the complexities of the human creative process. At most, we have the opportunity to gather new ideas about an artist whose work we have only casually known, as well as about art itself and its function in a larger context. Applause, then, to Robert Lee Morris and Artwear, for offering the public such an opportunity with a retrospective of the work of Kristin Moore.

Moore is an anomaly within the Artwear stable. In a galley where resins, rubber and the unexpected dominate, Moore creates primarily in gold and semiprecious stones. While her designs are consistently innovative, they are rarely startling and always wearable. And while most of these art jewelers rely on their multiple gallery sales and commissions for income, Moore sells an extensive line to major department stores and boutiques nationwide. In short, her talent and hard-won business savvy has allowed her to produce well-made, well-designed jewelry that has broad appeal. Yet, apparently, it meets the rigorous design and quality criteria that are the hallmark of the ground breaking Artwear.

The show, to its credit, included every piece Moore has designed in her 20 years in the field. The 200-odd examples were well displayed in five-year intervals from 1965 to 1985 and sometimes included photos of the artist from the period, as well as working drawings. The result provided a remarkable consistency of esthetic vision that was a delight to study and follow.

Moore designs pins, neckpieces and bracelets, but the backbone of her vitality has always been earrings. An education in sculpture is evident, as is her awareness of the human form. Her earliest necklaces and earrings are explorations of sensual line in space, employing thin gold wires in variations of curls and curves - some spiral, some referring to star formations, some ending in tiny pearls. An early design breakthrough for her was the extension of the actual gold design element to gracefully form the ear wire. These seminal pieces from the 60s clearly have the look of their time, when dangling earrings were in vogue. Yet, one notices in subsequent years her ability to return to the idea of the elongated wire curve, updating it, making it more minimal for one season, bolder for another, yet always, it remains her statement.

The work done in the years 1970-75 heralds a new direction. By using sheets of silver that were essentially folded, scored and cut, Moore begins to explore mass instead of line. Her earrings now gracefully sculpt and include the lobe, instead of using it as a display point. The forms seem to be inspired by nature, yet still have the curvaceous Moore esthetic. She notes that at this time she began to synthesize the lessons learned previously from the fabrication of her first efforts, with the on-going inspiration fine sculpture provides.

Also in these years, Moore made literal reference to a formal element that this viewer sees as quintessential to many of her ideas. This is the idea of a ribbon. Moore often seems to make inspired use of the infinite variety and linear mobility inherent in the casual drape of a single, long strip of fabric. A simple fold of ribbon could easily be the source for the design of a single line of curved and folded gold — a striking pin. In the 70s, the ribbon inspiration became quite literal — a pin took the form of an actual bow in sterling, with the knot accented in gold. Or the arms of a bracelet were the fluttering elements of a ribbon with the bow marking the center. Forms of this type are seen knocked off today; Moore, I believe, started them.

The breadth of ideas explored in these first 10 years are the basis for the later work. But the linear esthetic prevails, as does a willingness to explore new materials such as onyx, lapis, garnet and crystal.

The latest collection, made especially to coincide with the Artwear exhibit, seems like a radical departure at first glance. Large petalled cuffs, bold neckpieces hung on the body without structured closure and broad shield pins, all in silver or vermeil, mark a great change in scale. But the seeds for these successful concave and convex structural interplays, with their mobius strip references, were clearly sown in the collection of the 1970s. It is as if she now had the confidence (well-earned) to take some of the early concepts to their logical and contemporary conclusion. One is reminded here too, that often, Moore's ideas were ahead of their time.

The Kristin Moore retrospective showed the artist's development in a dazzling light. It had many lessons to teach. Other artists should remember the importance of maintaining a reference library of their own work, and other galleries should follow the Artwear lead to allow the public wider access to contemporary jewelry history. By providing such opportunities, we all have much to gain.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Micki Lippe: New York

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

October 21 November 14. 1984

by Betty Helen Longhi

A new look was seen from Micki Lippe in this show. Recognized for her elegantly refined jewelry using fused and reticulated silver, Micki is a master at controlling the subtle nuances of a line or form. In this new group of 25 pins, necklaces and earrings, the control has been released, giving the pieces a spontaneity and freedom. The carefully articulated lines have been replaced by quick slashes and dashes, long single pieces of wire intersecting the form or multiple combinations of wire crisscrossed in a grid work or arranged in parallel patterns. One wonders how much of this change results from her move from conservative Charlottesville, Virginia to Oklahoma. She admits that her isolation and lack of close contact with other jewelers has resulted in a turning into herself and her surroundings for inspiration. The use of long single lines is relative to the open spaces and wide flat horizons that surround her.

A group of brooches appropriately named Fragments was most evocative of this new look. In these, the sense of spontaneity is most evident. They are quick points in time, sketches in metal. These pieces effectively show off her recent inclusion of color, using copper-flashed brass, which is heat oxidized to rich purples, blues and bronzes. Another series of brooches and earrings maintained Lippe's fused and scratch-brushed fine silver surfaces familiar in earlier work. Accentuated with small squares of gold as points of color and richness, these pieces were most effective in their lightness, delicacy and wearability.

In noticeable contrast to her brooches and earrings were the three major neckpieces in the show. The first two Antique Red Beads and Black Onyx Beads employed pillow forms in fused silver and gold as central elements in a multistrand bead necklace. The follow-formed pillows appeared rather heavy and did not relate well to the beads. One felt they were contrived in an effort to participate in the current popularity of beaded necklaces. In marked contrast, the third neckpiece Black Shell Beads was unique for its elegance and simplicity. Composed of a single strand of black shell beads with a central pendant of hollow-formed, heat-treated brass and two simple pieces of forged silver it had a refined but primitive appearance. Strong and direct, one could envision it on the neck of an African priestess. According to Lippe, this necklace was inspired by her interest in African and Oriental art and is a blend of the two esthetics.

A small brooch entitled Picture Frame was notable for combining the best of Lippe's earlier style with the freedom and color of her new work. A scene of sterling silver trees on a background of heat-colored bronze gave the impression of infinite distance. This was enclosed by a frame of fused silver slashed at the bottom and "buttoned" together with tiny gold squares. The constrast of the expanding imagery of the picture and the containment of the frame held by these two points of gold gave a wonderful feeling of tension and excitement.

In her statement, Lippe says her concern is to make her jewelry as vital and interesting as she can and still have it be wearable. She has certainly accomplished that in this exhibition. One can only look forward to more exciting work in the future.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jude Ortiz: Goldsmith

Art Gallery of Algoma, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada

September 18 October 16, 1984

by Jean Burke

One of the North's most outstanding goldsmiths, Jude Ortiz designs clean, uncluttered jewelry, reflecting a spatial quality that is the true essence of northern Canada. Her work in this exhibition included a brooch Celestial Compass, which combined 14k gold and sterling silver with ebony. Of note also was a pendant Whale Life Saver an indication of the artist's intense interest in environmental preservation.

Another outstanding piece was a brooch/fibula of 14k gold, titanium and seed pearls. Ortiz is a graduate of the Jewellery Arts Program at George Brown College in Toronto but has since returned to northern Ontario where she operates her studio near WaWa overlooking Lake Superior.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rick Dingus, Jon Havener, Fred Parker

Gallery Karl Oskar, Westwood Hills, KS

January 4-29, 1985

by Ann E. Erbacher

The metal sculptures of Jon Havener, a metalsmithing professor at the University of Kansas at Lawrence, were exhibited at the Gallery Karl Oskar along with the photographs of Rick Dingus and Fred Parker. Havener's sculptures had a dramatic and powerful presence that overshadowed the two-dimensional work of his coexhibitors. His sculptures are a study in complexity and contrasts.

Havener's pieces here had a menacing quality, due primarily to two factors: their angular and sharply pointed forms, many of which were reminiscent of arms and armor, mostly knives, swords and helmets, and their dark coloration, consisting of varying shades of brown and black. Their aggressive appearance was reinforced by the artist's choice of titles: Guarding, Crusade, Entrap. Guarding was reminiscent of armor in general and of a Spanish conquistador's helmet in particular.

The influence of Cubism is strongly evident in the fragmentation of Havener's forms. The sculptures depicted several aspects of the same object simultaneously in a manner that clearly draws upon the Cubist tradition. The concept of time, so important to the Cubists, was also a concern of Havener's in these pieces. They are contemporary, yet appear to have been transformed over a period of time. The selective use of a green patina to accentuate certain details, in Tri-pod, for example, gave the weathered appearance that copper alloys develop over time. The organic coloration complimented the dynamic forms of the pieces. In this work, time was suggested with the idea that as a form ages and erodes, it breaks down into fragments. The resulting forms did not have the appearance of decay, but rather of growth and life. They were so filled with a sense of captured energy that one could almost imagine that they were undergoing metamorphoses as they were being viewed. The viewer was invited to examine these sculptures from different angles, to explore their every facet. Their mysterious, enigmatic quality was emphasized by one title: Enigma, although this was certainly not the only piece in the exhibition with that quality.

Havener attempted to integrate the sculptures with their bases, and did this well, for the most part. Tri-pod, however, did not achieve this integration as successfully. The abrupt transition between the curvilinear elements in the upper portion and the linear elements of the base was disturbing. Crusade and Enigma were better integrated, due to the inclusion of more linear elements in their upper portions, providing a smoother transition to their bases.

On the whole, Havener's pieces were very strong and worked quite well. It has been interesting to watch his work evolve and to see how the formal concerns of his smaller-scale, functional pieces carry over into his larger-scale, sculptural pieces. This exhibition provided a good, representative sampling of his recent sculptural work.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Collectors & Collections

An International Jewelry Symposium, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York City

March 30, 1985

by Charles Lewton-Brain

Forgery techniques, medieval Jewish wedding rings and Cartier mystery clocks were among the subjects covered at the recent one-day symposium at F.I.T. Organized by Jean Appleton, the symposium brought together speakers from England, France and the United States as well as participants from as far afield as Ireland, Hawaii and Michigan. The broad theme attracted collectors, dealers, museum employees, manufacturers, benchworkers, freelance designers and hobbyists.

Perhaps the one-day format and short presentations contributed the strong sense of vitality and excitement that carried through the day. Coffee breaks and lunch provided people with time to meet, make connections and interrogate the speakers.

Subjects addressed were Classical Jewelry (Jack Ogden) , Castellani and Revivalist Jewelry (Geoffrey Munn), Renaissance Jewels in the Collection of Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza (Anna Somers Cocks), C.D. Fortnum and the Ring Collection at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Diana Scarisbrick) and Art Nouveau and Art Deco (Ralph Esmerian). Lectures were followed by a roundtable discussion and question period, which included Mr. Destino, president of Cartier and Mr. Curiel, vice-president of Christie's.

Presentation styles varied from animated (Ogden) and desiccated (Scarisbrick) to great emotive salesmanship. This last was epitomized by Esmerian describing a face on a Lalique piece with "That pure naiveté of the Bretagne child" and later when speaking of some of Lalique's work "that mystical, depraved sense of the other side of Art Nouveau, that seamier, demonic side of man".

Ogden's presentation offered much anecdotal and technical information. He proposed four areas of consideration in evaluating and understanding the ancient jewelry object: 1) Supply of raw material, mined, alluvial gold, melted works of conquered peoples or obsolete fashion and coin. Political, economic and geographic factors have to be examined to understand a work. 2) Technical knowledge, as revealed by hearsay and pictorial evidence as well as analysis, this last illustrated by a number of intriguing photomicrographs of ancient pieces demonstrating their manufacture in a sheet metal technology (1/100 of an inch diameter wire made by rolling twisted sheet between flat surfaces). The descriptions of forensic analysis in the context of discovering forged ancient works was of special interest. 3) Individual skill and knowledge. The point here is that it is not material value but skill and craftsmanship that "transcend the centuries" to give a work great contemporary value. The assertion that a modern worker using the original techniques to deliberately copy an ancient piece would produce a perceptively different work suggested that work is really of its time in cultural as well as technical terms. 4) The customer—without one there is no jewelry. Evaluating a piece of jewelry in its social and economic role is the last and most important consideration. The customer is in a sense the force that produces the work.

The other presentations were valuable in placing jewelry from about 1400 to 1850 in various art historical and stylistic contexts. The carefully chosen works shown were masterpieces of their times and styles.

Esmerian's presentation on Art Nouveau and Art Deco jewelry and objects was exquisitely illustrated by his own slides and various works brought gasps from the audience, perhaps as many could relate better stylistically to them than to earlier works. It was exciting in part because of his descriptions (mellifluous hucksterism) and was supported by his establishing a good historical and corporate context for the works. Details such as Lalique's use of plastics and mixed materials intrigued participants.

The roundtable with Curiel of Christie's and Destino of Cartier consisted of a question-and-answer session and provided insight into the world of very expensive and historical jewelry sales and markets. A contemporary Parisian jeweler named Jaa was mentioned, whose work is in such demand that one man registered his two-year-old son to have his future wedding rings made. Homage was also paid by Destino to the large number of young jewelers working in nonprecious materials for the fashion market. Finally, Esmerian's comment that an artist's creativity lasts only 15 to 20 years elicited protests from the audience.

This symposium was well organized and presented, the speakers were among the best and the audience animated. The one-day format maintains a pitch of excitement throughout. F.l.T. plans to develop a series of such mini-symposia including one in November 1985 to coincide with the exhibition of the largest group of Lalique works in one collection on loan from the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, Portugal.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Passing Out

John Holden Gallery, Manchester Polylechnic, Manchester, England

November 6-23, 1984

by Peter Gainsbury

Passing Out in 1984 was, for the first time, held outside the City of London and Goldsmiths' Hall. It represented final year work of silversmithing and jewelry design courses at 22 art and design colleges around the British Isles, offering Higher National Diploma and BA(Hons) Degree level courses. The selection of pieces was up to each college. Also represented was post-graduate work from the Royal College of Art.

Each design course has its own character as was visible from the displays, although there were common elements of design and technique. The three-year degree courses in design follow a one-year general art and design course, often taken at a different college. There are also two degree courses in the London area that incorporate an extra "sandwich" year spent in industry, and the Scottish system involves four-year degree courses that incorporate the general first year at the same college. The two-year Higher National Diploma courses follow a two-year course at Ordinary National Diploma level, thus equalling the four years total of the degree courses. These higher diploma courses are new, and the students finishing this summer represented the first "crop," with some exciting results. There is a slightly greater technical emphasis to these courses than in the degree courses, but they have not yet been going long enough for their philosophy to be judged by their results.

Inventiveness was shown to a high degree by many of the designers of the pieces on exhibition, and although the pieces were not always high level, virtuosity was fairly frequently noticeable in the exceptions. Students of three or four years are only beginners after all, and these skills have taken the men who utilize them a lifetime in the trade to acquire. In England the traditional high level of skills involved in both the silversmithing and jewelry industries has been severely depleted by the disappearance of many well-known firms.

The Goldsmiths' Company is most concerned to maintain the high level of design and craftsmanship traditionally associated with the silver and jewellery industries. The so called "alternative" industry, composed largely of individual designer-craftsmen creating original pieces in small workshops, has been set up by the predecessors of these same students, who have found that the only way to get their ideas through to the public is to make and market them themselves. This has been a refreshing, welcome development. The communication gap still needs bridging between the expertise of established people in the trade and the innovative approach of young designers.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Gary Griffith’s Jewelry and Constructions

2 Tips for a Successful Jewelry Collection

Dan Feldman: Allegory of Love

Metalsmith ’95 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.