Metalsmith ’85 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

37 Minute Read

This article showcases the various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1985 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Christophe Burger, Stanley Lechtzin, Vernon Reed, the Mitchell Museum and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Christophe Burger

Elaine Pottery Gallery, San Francisco, CA

August 21—September 15, 1984

by Carrie Adell

Christophe Burger came to California from France to produce a collection of jewelry for exhibit at the Elaine Potter Gallery. He wished to avoid the hassles of customs, and he was interested in the challenge of creating a collection in another country, in another goldsmith's studio, in a very limited time—less than a month.

I first viewed the work when it was delivered to the gallery. It was laid out on a table. I could pick up each piece, try it on. (All were wearable, all carefully made.) As my eyes wandered over the pieces, I looked for the creative process, the sequence of experiences, the begetting of new images from new ideas.

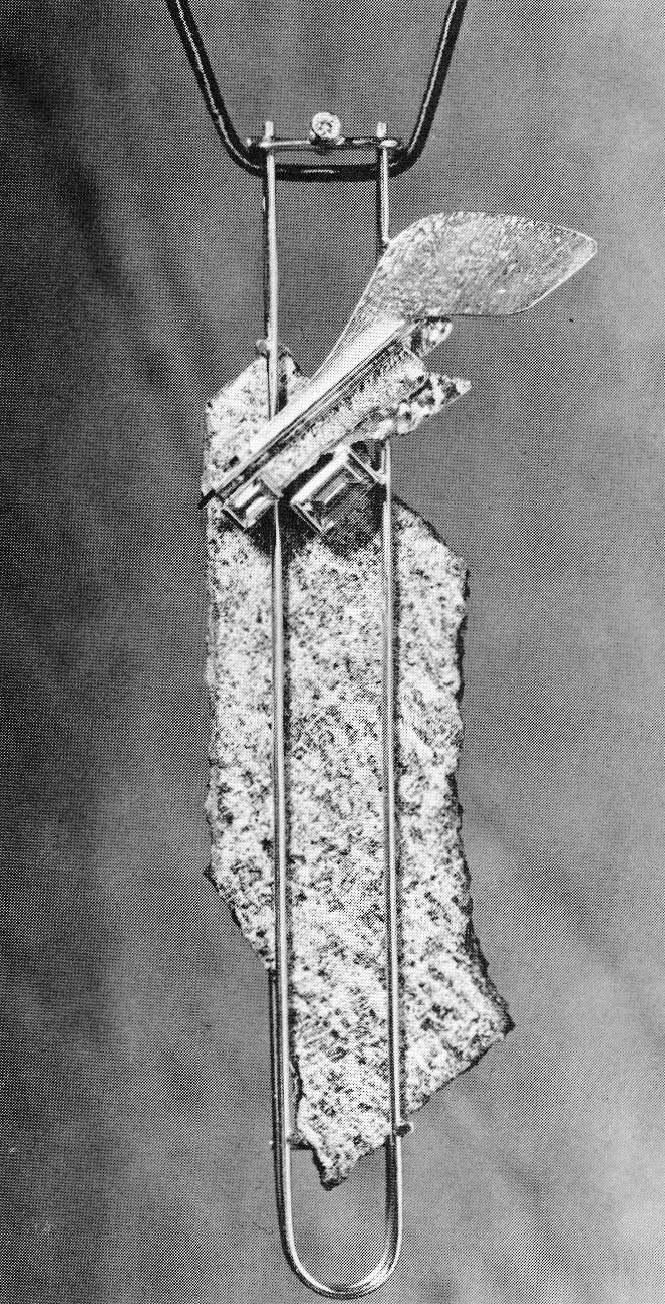

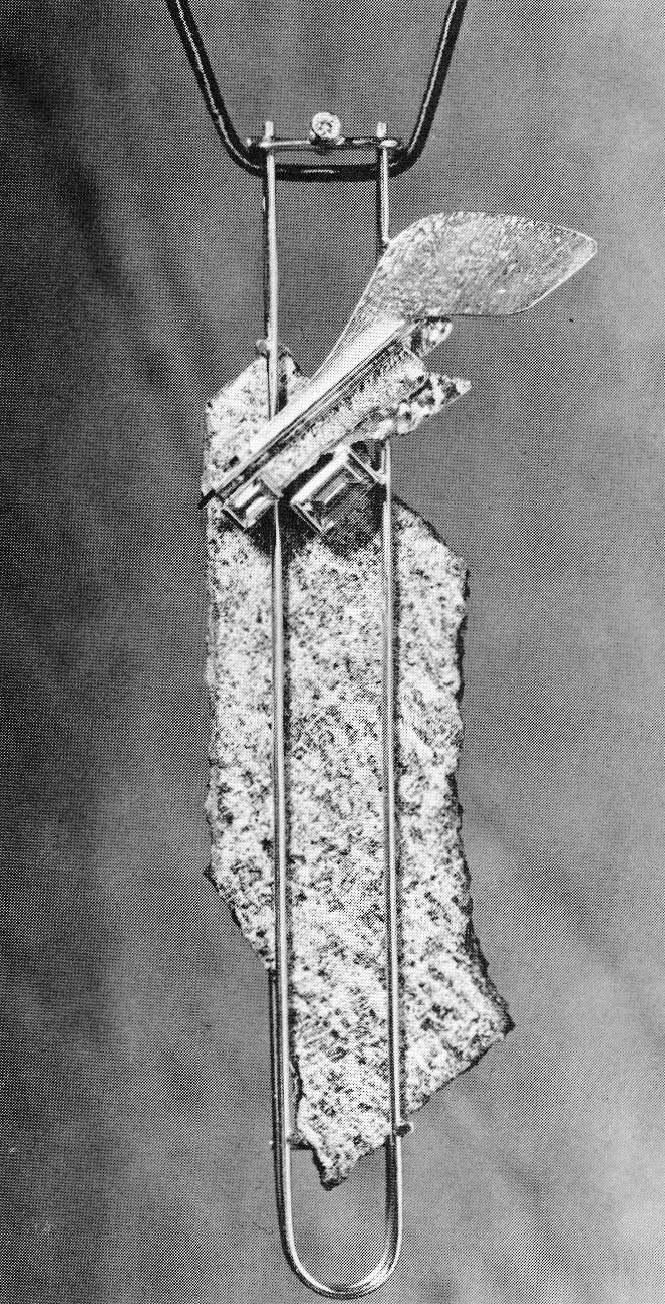

My attention was drawn to one pendant in a group of related pieces, each with a bannerlike form. This must be the first in the series, I concluded. The pendant tapered from left to right. My eyes sought the connection between the freely composed tip of the banner form, undulating on the right, and the rest of the banner, tightly constrained by the framing bars of a strong 90″ angle on the lower left. It appeared that the piece grew from the right side, yet I was reading it from left to right. The first process in its design must have been Christophe Burger picking up some triangular and curved, roller-printed scraps of silver left by the studio's owner. I could imagine him fooling around with these scraps, arranging and rearranging them to find an interesting image, a point of departure. I remembered pushing around geometric paper shapes in my first experience of collage in high school. I got the feeling from the work that Burger would be a playful person, open-ended in his explorations, yet disciplined.

One clue was his ability to complete the collection. There were 18 pieces of jewelry produced in 14 days. The second clue was the skill with which Burger brought together the disparate elements of the aforementioned pendant into an organized yet lively miniature collage. Here the layered assemblies were of soldered and riveted precious metals and other hard materials, rather than of paper, fabric or fibers. Here, too, I found the sense of adventure, of spontaneity, of painterliness and, mostly, the evidences of process, which makes collage so appealing esthetically.

The image the artist developed in that first pendant was elegantly refined in several succeeding variations, using other "found" elements, as well as those of his own fabrication. Each of the roughly triangular pieces is organized within two hard-edged sides, opened to the right or upward. The third side is freely expressed by a ragged edge, a softly organic fold, a series of saw-cut striations, an unexpected material. Here and there within the order and discipline of the various triangles appears a whisper of disorder, a hint of disruption, a discontinuity in a highly structured field (I wonder if he takes time to kick up his heels during periods of intense productivity?)

Beyond the expected 18k gold, silver, diamonds and other gemstones, Burger uses carved granite, zinc and screen-masked and flame-patterned titanium. The softly-colored blues and grays of these materials echo the range of gray values produced by the many screen-patterned silver surfaces.

I found that Christophe Burger likes to use certain visual elements in almost every piece, whether as another point of departure, a constraint in which to design or for a sense of completion. All the pieces contained two strong linear elements, often a kind of frame. In each jewel the eye moved from left to right and the composition was stabilized by a circular, or nearly circular, gemstone. Those pieces without gemstones had round rivets or circles that were roller-printed or flame-colored through a circular grid.

Christophe Burger is a dedicated "do-er." He enjoys surprising the viewer with the unexpected use of unusual materials His juxtapositions of rough and refined surfaces are mutually enhancing. Reviewing the installation of Burger's work brought yet another surprise. In addition to the well-arranged vertical cases full of jewelry were six small sculptures that he had made in the two days between our last meeting and the opening of his show Two boulders, fist- and head-sized, their cord wrappings with residues of raised lines of sandblasting process on their surfaces recalled spare Japanese images. The other four objects were related in materials and in their generally high-tech look, each varied from the others in nuance and visual direction, all demonstrating once again the virtuosity with which Christophe Burger celebrates living, his economy of organization, clarity of image, crispness of style and his process of creativity.

Stanley Lechtzin, Vernon Reed

The Works Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

May 2-June 3 1984

by Vickie Sedman

Recently The Works Gallery held concurrent exhibitions featuring new work by Stanley Lechtzin and Vernon Reed. Although scheduling the two together was coincidental it provided an exciting and interesting exhibition Lechtzin and Reed are both pioneers who have tailored technology to meet their conceptual needs. The fact that their work is so different, both in esthetic and conceptual concerns, is the very reason that simultaneous viewing proved stimulating and thought-provoking.

In recent years Stanley Lechtzin has continued to grow and evolve as an artist, although the basic format of his work has not radically changed. What I find most significant about this man and his work is that he has made a whole generation of goldsmiths conscious of the artistic possibilities of 20th-century technology. Our technological society has given artists incredible freedom to express themselves. Lechtzin has fused the electrochemical process of electroforming with organically conceived forms that are bold, dramatic and extremely personal. Each and every piece makes a statement which reflects the intensity of his personal vision and says as much about the artist as the person who would wear it. One cannot help but admire work which represents the mark of a real individual.

The pieces, though large in scale, are extremely lightweight and wearable. The work has a sensuous linear arrangement that is reminiscent of Art Nouveau, yet the structural and sculptural aspects seem to be Lechtzin s primary concern. In many of the pieces he does not enclose the entire form, thus exposing the internal structure of the piece. The interiors of these pieces are matte in finish and emphasize the sculptural quality of the work.

Lechtzin uses semiprecious stones, crystals and pearls as either accents or focal points in the work. Sometimes they are used to draw attention to an opening or an interior form in his structures. For example, in Torque #70E, a crystal is suspended in a concave form, reminiscent of a stalagmite in a cave. Pearls are used on a ridge to highlight a slight opening.

Lechtzin's pieces are grown in an electrolytic solution. The process is analogous to numerous growth processes observed in nature and is a source of stimulation which has great meaning for him. His pieces directly reflect and suggest growth processes as they direct your eye through space, flowing, tapering and changing direction. His use of texture also resembles growth patterns; in many of the pieces the surfaces are smooth and passive, contrasted by very active and organic sections. The surfaces flow, twist and turn, establishing an integral relationship between surface and form. In the most recent work Lechtzin utilizes both black nickel and 24k gold finishes. The combination of these two metals adds contrast and additional drama to the work.

The overall impression is that Lechtzin's work represents an artistic integration of process and concept, form and function l think Lechtzin has been and will remain an important contributor to the field.

Vernon Reed, also a pioneer in his use of 20th-century technology, is exploring the visual capabilities of microelectronics in jewelry. His use of liquid crystal displays as a design element adds a sense of time, movement and rhythm to the work.

Reed uses photo-anodized and colored titanium to create bold and powerful graphic images. His work continues to speak to the issues of man's isolation in an era of sophisticated technology. Another common theme in his work is man's inhumanity toward man, which is usually depicted by juxtaposing images of people and war machines. Reed's images move and pulse, changing position as they appear and disappear. In exploring the question of humanism in an age of technology he uses bright colors, suggesting the triumph of the human spirit. The work's prophetic nature seems to be warning us of man's possibly disastrous future.

In Reed's most recent work he seems to be having more fun, drawing on fantasy as a source of inspiration. His piece Battle of Pobillo XIK-Dawn is reminiscent of a primitive cave painting, possibly from another planet. It is a wall piece depicting two warriors from a fantasy world facing each other holding spears. A liquid crystal display resembling a radiating sun separates the two figures.

Reed's work is concerned with the impact of a graphic image. The artist tries to minimize mechanisms and devices for attaching his pieces to the body whenever possible so that nothing interferes or competes with his imagery. His images are constantly moving, powered by one-year batteries. The latest work comes with an acrylic stand. This was a logical direction for Reed because these pieces can now be displayed when they are not being worn.

Vernon Reed was not trained as a jeweler or metalsmith. He is as interested in science as he is in art, and because of this he brings a unique perspective to the creation of jewelry and metalwork.

Jewelry and Beyond

Mitchell Museum, Mount Vernon, IL

April 21 - May 30, 1984

Fashion Institute of Technology, NYC

June 7 - 17, 1984

by David Prince, Curator, Mitchell Museum

The purpose of "Jewelry and Beyond" was to examine recent examples of metalwork and jewelry in an effort to identify significant new trends in esthetics and technical experimentation. Requests were mailed to distinguished members of the Society of North American Goldsmiths asking for an example of their most current work. Eighty-seven artists responded and the resulting group of objects was almost overwhelming in its diversity. Gradually, however out of this eclectic group came the message that, in general, metalwork is moving out of the realm of crafts and into the main stream of contemporary art. Clearly, the strongest works in the show were those attempting to assimilate the formal concerns of contemporary art into the size and scale of traditional metalwork.

What makes this evolution so interesting is the central problem faced by metalsmiths of developing and maintaining a distinct identity both individually and as a group. Historically, metalsmiths have been perceived as artisans whose purpose was to make objects of functional and/or decorative merit. Their pieces were usually small in size and meticulously crafted from fine metals and other rare materials. Contemporary metalsmiths have become frustrated by the restrictions imposed by this legacy and have begun to experiment with new techniques and materials in a search for an esthetic alternative. Jewelry and Beyond exhibited several new approaches to the field.

Most clearly seen in the exhibition was a strong movement towards creating pieces addressing purely sculptural concerns Gary Griffin's large , freestanding steel construction defiantly challenges the historical definition of metalwork in its use of common material and boldly constructivist composition. Richard Helzer uses a variety of materials to form a tablelike structure on top of which is a surrealistic landscape made up of independent metal elements. The tabletop itself is a piece of white acrylic overlaid with a blue acrylic grid pattern. This grid unifies successfully the diverse elements of this very personal composition.

These examples stand in sharp contrast to John Marshalls Wing Bowl and Ron Wyancko's Silver Subterranean. Marshall and Wyancko perpetuate a style popularized by Scandinavian artists in the 1940s. Their pieces are straight forward and emphasize a cleanness of form and a smooth, fluid line. Unfortunately, both fall to inject new life or meaning into this now dated stylistic lexicon.

Between these two poles there are a group of artists who have integrated successfully the concepts of historic metalwork into a personalized format that asks to be judged solely on contemporary esthetic merits.

A fine example of this work is inner Stability by Thelma Coles Using sheets of copper and stainless steel rods, Coles creates an open, domestic looking structure. The house rests on a series of stilts that pierce the floor and extend up into the interior. They then split apart and fill the structure like reeds waving in a marsh. The subtle tension created by these interwining rods is harmoniously juxtaposed by the clean line and carefully proportioned size of the surrounding house.

A similar sense of harmony is established in Barbara Minor's Flight from Water to Water. Like Coles, Minor is able to create a work that is refined and elegant. The true success of the work, however lies in her ability to inject a personal attitude and stylization that distinguishes the work from other pieces fashioned in the more aloof International Style. She achieves this through a deft and marvelous use of enamel coupled with a sense of form and composition that binds the various elements of the piece into a tightly knit whole.

In the exhibition's examples of jewelry there could also be found artists breaking free of past traditions.

One of the most ambitious is Enid Kaplan whose Figures in a Landscape integrates a pair of earrings into a similarly scaled, highly expressionistic three-dimensional landscape Kaplan adds further excitement and visual movement to her sculpture by making vivid use of the color potentials of the various titanium and niobium elements.

Kim Bass stays strictly within the bounds of jewelry and, nevertheless, manages to create a piece of wonderful freshness and humor. Her two-pin set Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs presents the major characters of the fable as tiny cloissonnéd enamel pins. The figures are near to being caricatures, each having his or her own identifying symbol. One pin combines the wicked witch, the sleeping princess and the attending prince while the other portrays the seven dwarfs. Through this strongly personalized concept, Bass transcends the historic parameters of jewelry and moves into the wider ring of fine art.

Artists such as Bass, Coles and Minor succeed in lifting themselves out of the role of craftsman into the role of artist because they initiate their work from an intense point of view, creating work which is completely self-sustaining.

Peggy Johnson—Housewearables: Jewelry

The Works Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

June 10-July 3, 1984

by Alida Becker

It's small wonder that Peggy Johnson credits Lewis Carroll with inspiring at least one of the cunning assemblages in her tiny household of wearable art. In fact, there's a delightfully other-end-of-the-looking-glass quality about all this work, which features small-scale utensils doing double duty as earrings, a toaster or a radio plugged in as pins and a necklace that dangles sterling silver pots and a frying pan of 14k gold.

There's enough careful detail here to satisfy the miniaturist with a flair for 50s nostalgia, but at the same time a slightly fantastical whimsy intervenes. For while Johnson does produce the occasional single piece, she seems to have much more fun concocting clever little mix-and-match sets. Thus her sterling silver soup tureen opens to reveal a sterling and pearl necklace, which can be further adorned by a gold ladle that easily hooks into place. The necklace, by the way, spells out "beautiful soup" —with a bow to Carroll's "The Mock Turtle's Song."

Peggy Johnson, Housewearables, oxydized sterling silver, 14k gold, cake—1 x ½".

In a similar fashion, a sterling silver bowl (whose parts are adaptable as earrings) is stamped with the phrase "life is just a bowl of cherries." And, sure enough, right there inside is a string of carnelian beads. Even more elaborate is Johnson's version of the all-purpose department store wok set: an eight-piece, made-to-scale collection including a copper-lined wok with a cooking stand and various racks, a string of 14k goldfish on a silver chain and a pair of 14k gold chopstick earrings.

One can easily imagine Carroll's heroine Alice delightedly choosing between all these tiny surprise packages. Will it be the copper casserole with a necklace of stamped copper carrots? Or the "fine kettle" of sterling silver fish? A vegetable soup pot in which earrings masquerade as tomatoes, onions and the like? A silver trout necklace in its own poacher? Or baby peas in jade. simmering in a silver container?

Perhaps the piece that best sums up the appealing good spirits of the whole collection is Johnson's five-piece birthday cake set: a silver pendant in the shape of a cake, with a chain coiled inside its own stand, decorated with two pearls that detach to become earrings. It's the perfect celebration of the pleasure this artist obviously takes in her meticulous craftsmanship, a pleasure that's almost impossible to resist.

Jan Yager

Swan Galleries, Philadelphia, PA

May 23-June 23, 1984

by Barbara Satterfield

Jan Yager's work is like a Japanese Haiku. It is spare in format but rich in metaphor. The work comes from a contemplative spirit, one that gently enjoins the viewer to participate in the maker's meditations.

The Oriental flavor of Yager's work permeated the 63 pins, necklaces and earrings recently on display. Not surprisingly, Yager says that while working at the museum at the Rhode Island School of Design as a graduate student she was influenced by the textile patterns found in Japanese kimonos and in the shapes of mid-Eastern cuneiform tablets. Texture and form are probably the most pervasive features of her work.

During graduate school Yager began to explore the potentials of the tablet form in making what she calls "precious little objects to hold " These objects, with puffed ridges, metal feathers, appliqued apple slices, or "stone spots," beg to be handled and fondled She thus encourages an intimacy between the viewer and the object. The reference to the kimono is clearly present in the earlier, more formal, raised patterns Yager stamps onto her forms.

In 1980, while at RISD, Yager began research for her thesis. Working in Providence, in close proximity to the jewelry industry, she was inspired to use technology for production purposes. Using a hobbing, or coining, press she first stamps her texture onto the metal (usually sterling silver) and then uses a small hydraulic press to push out the forms Yager is particularly adept at using these techniques to best advantage. Each piece is then cut out and fabricated by hand. Although she is willing to use technology, she finds the "machine esthetic" unappealing, and does not want it to dominate her work. She developed her "Whomp and Puff" series as the ultimate antithesis of the machine. Even though she uses almost exclusively pure, geometric forms, corners of her pieces are rounded and each form is pillowed. In most cases a layer of fine silver is built up on the surface, which is then left with a soft white finish. These soft and rounded pillow forms have a particularly feminine and sensuous quality.

A recent move to Philadelphia and the advent of the Swan show prompted Yager to develop her work a step further. She started by creating some new, more organic textures which she applied to her familiar forms. Instead of using the forms singly, as she had done in the past, she began to combine them, stringing them on thick chains, leaving the elements free to move and be moved. They now invite the wearer to participate in the piece by deciding the positions of the various components. The mobility of the units, the inclusion of different shapes and the potential variety of compositions make these necklaces more interesting and more playful than single units hung from a chain. There is the added auditory bonus of the pleasant sounds these units make as they clink against each other.

Yager's work evolved even further with the addition of odd little stones deftly juxtaposed with the handmade metal forms. She has collected these stones over the years for their simple shape, color and texture. Most of the stones are Petrosky, the state stone of Michigan, her home state. These unpolished stones, smoothed only by the ravages of nature, evoke a sense of mysticism and magic. Because they are primal, their juxtaposition with objects that are clearly of the here and now is at first disquieting. Upon further reflection, however, we see that each stone provides a subtle counterpoint to the man, made forms in metal. These new pieces seem to evoke a sense of Yin and Yang, man and nature, old and new, a harmony of disparate parts. They are a step beyond the purely decorative because they ask us to question and to think about relationships.

Yagers work is not exciting in the sense that it dazzles us with technical mastery, or with its innovative use of new materials, or with the creation of new forms. Her work has not developed in leaps and bounds. Rather, the work is a progression of little steps, a slowly evolving process of thought and feelings. The work is like the artist: calm, contemplative and serene. It speaks softly, encouraging us to leave the chaos of our everyday lives and take the time to listen, to feel, to get in touch with what the work has to say. The necklaces have the quality of worry beads, and one can visualize these pieces generations from now, passed down through families who have loved them and handled them to the point where all the texture is simply worn away.

Paul A. Lobel 1900-1983, Memorial Exhibit

Hudson River Museum, Yonkers NY

June-July, 1984

by Cynthia Cetlin

Paul A. Lobel, a Rumanian, studied at the Art Students League in New York, becoming a designer, sculptor, silversmith and craftsman in many materials. In 1925, in a one-man show in Paris, he exhibited drawing, painting, etching and metalwork.

Lobel was a well-known artist in Greenwich Village during the 40s and 50s. His beautiful and popular jewelry was widely influential to a generation who learned from his skills and innovations. He is best remembered for his abstract sculpture first celebrated in an exhibition called "Shining Birds and Silver Beasts" at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

This memorial exhibition of 26 sterling silver sculptures of people and animals done by Paul Lobel reflected that artist's awareness of popular trends in 50s design. The influences of Picasso, of African art and of the biomorphic abstractions of Gorky and other painters had affected craft design. Lobel's small sculptures, particularly Bison. Charging Bull and Toreador are reminiscent of Picasso's bullfights and of the work done at Antibes; many of the human and animal faces in Lobel's work recall African tribal masks; and the sleek, organic abstractions of both animate and inanimate objects are distinctive of 50s art and design. In this group of sculptures a recurring mood of whimsy, liveliness and naiveté reflects the optimism and innocence of the time. Many of the sculptures, such as Cat on a Stick, Together, Fiddler on a Cello and Adam and Eve are narrative, humorous, sometimes cartoonlike.

The technically simple construction of the sculptures is appropriate to their naive, primitive quality. The structures are very well made and sturdy, constructed from heavy sterling sheet and wire. These works, although executed with a mature facility, display a limited technical range consisting of forging and tapering, soldering, piercing and a limited amount of forming. As sculpture, they are quite frontal and need only be viewed from one angle, a fact which reinforces the impression that Lobel was primarily influenced by two-dimensional art.

VII Biennale International l'Art de l'Email

Chapelle du Lycee Gay-Lussac, Limoges, France

July-September, 1984

by Kathryn R. Gough

Of the 1000 pieces submitted to this biennial enamel exhibit, 300 pieces from 25 countries were chosen to be shown. This year for the first time there were enamels from the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union The invitation was extended to these countries with the understanding that all pieces sent would be exhibited without being submitted to judging.

The Chinese sent a four-man delegation with an interpreter. The men represented small factories (their business-card stated: Arts and Craft Corp of Ministry of Light Industry) which produce the traditional Chinese cloisonné that we see in the United States and consequently was the work on display at this year's exhibition.

The real excitement and surprise was the Russian enamels. A number of the enamels portrayed political and human-rights issues. A member of the Biennale staff told me, We couldn't believe our eyes when we opened the boxes. The Russian authorities must consider enameling such a minor art that they didn't censor the shipment " The stark simplicity of Fenetre I and II conveyed much meaning. Fenetre I was a photoetched metal sheet of a stone wall through which a window had been cut. Behind the window was mounted an enamel treetop. Fenetre II was a photoetched brick wall, and behind the two cut-out windows was a brick wall, beautifully enameled in various shades of red and orange. The wall piece Kremlin was a constructed venetian blind, on the slats of which was a silhouette of the Kremlin. The wall piece Man and Environment portrayed human figures with raised and grasping arms. There were other Russian enamels (38 in number) showing peasant scenes of men shearing sheep and other activities. No Russians attended the conference, but two older women came from the satellite countries of Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

The VII Biennale was an excellent enamel show The French have invested much time and effort in making it a successful international view of enamels. Five awards were given this year: Marianne Duntze, Germany, received an award for her cloisonné wall plaques; Valsis-Capelleja, Spain, for his mixed media eternal female portraits; S. Klopsch, Germany, for abstract wall murals; C. Christel, France, for his sculptured enamel goblets, and Kathryn Gough, USA for jewelry.

The Aquarellist and The Smith

Art Center, San Luis Obispo, CA

May 26-June 17, 1984

by Barbara Young

The strong shift of focus that has occurred over the past decade in metalsmithing, from art form to designer piece, is well reflected in Crissa Hewitt's work. Within this period, economic forces, really global macroeconomics, and our own evolving social trends have had profound effects on the world of metalsmithing, as every smith well knows. With a net profit of 5% on a wholesale gross of $100,000 sales yielding only a national average income, the scramble to learn production methods is clearly the only race worth entering.

However, some smiths have not opted for the money game and still prefer to work as traditional craftsmen, not production designers, and Crissa Hewitt is one such person. The very nature of this exhibition tells you that much.

This exhibit was a collaborative effort between Hewitt, professor of metalsmithing at Cal Poly, and Fred Lauritzen, professor at Cal State University in Northridge. Hewitt was Lauritzen's student before going on to Cranbrook. Both exhibited metalwork and Lauritzen exhibited watercolors and prints, making a very pleasant combination that, in a sense, took one back in time when art and craft were good words to use. Design, designer and designerly were yet to come.

The primary sensibility that motivates Hewitt is touch, and the container is a favorite form; hence, many of her pieces have to be handled to be appreciated. They are heavy and solid with nice, snappy, clicky closures, well engineered. Crissa says she has no desire to make lightweight pieces. "Maybe this is a luxury because I am not trying to make the last dollar on every piece." Remember?

Several factors combine to make one feel to have stepped back in time in viewing this exhibition: some of the materials used and their treatment, the intimacy of the esthetic and the high touchability rather than an anonymous high-tech look. These are friendly pieces.

Perhaps the most personal example of work was the little sculpture Homage to Mine Eyes which contained Hewitt's eye-glass lenses in use before 1982 when she underwent double cataract surgery. It was only post-surgery that she was able to realize how much vision she had lost, gradually, over a period of several years. Today she wears contact lenses and glasses and, quite rightly, has gained a renewed confidence in herself, partly due to an increased physical mobility. The past two years she has begun studying large-scale bronze casting learning the traditional methods, as are many sculpture students today an interesting trend in itself.

For whatever reasons, Hewitt pursues the traditional craftsman's path, responding to material, loving the way it feels and searching for ways to transform it by her own vision and pass it forward as a finished product to be enjoyed by others.

Some analysts are predicting a still different configuration to the art-craft-design triad for the 1990s, with the high-touch need only increasing in parallel with the evolution of our high-tech society. One well-known source of this idea is Naisbitt's Megatrends, but others are saying it too, including government sources. I cannot see how it will work economically, but then the first antique piece of jewelry to crack £1,000,000 in a London auction house only happened two years ago.

Fundamental traditions just don't go away forever.

Linda Weiss-Edwards and John Edwards: Jewelry

Running Ridge Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

August 3-22, 1984

by Lane Coulter

For this exhibition the Edwards, a California couple who have been working collaboratively since 1979, created an elegant group (21 pieces) of wearable jewelry, primarily in 14k yellow gold with additions of pearls, diamonds and colored gemstones. The emphasis of the jewelry is on forms reminiscent of sand dunes. In keeping with this theme, their major work for the past three years, and for this exhibition, has utilized large fresh-water Biwa pearls carefully selected for their rectangular shapes. Many designers would allow the strong forms and seductive surfaces of the pearls essentially to become the piece, to dictate the design and to allow the metal to be used as hardware or to be diminished in its emphasis. The Edwards meet the challenge of these incredible pearls head-on, inventing gold shapes equaling both the strength of the forms and the sensuousness of the surfaces.

The gold forms in the work are strengthened by the use of sequential shapes with a change in size of the repeated units. The soft volumes create edges of a smaller scale, while the glowing texture of the finely sandblasted surfaces replicates the delicate qualities of the pearls. This interplay of the manmade and the natural creates a variety of visual complexities for the viewer. Additional jewelry in the exhibition combined formed and cast gold elements with very complex forms in translucent stone.

Multiplicity in Clay, Metal, Fiber

Skidmore College Art Center, Saratoga Springs, NY

July 7-September 23, 1984

by Cynthia Cetlin

According to its curator, Regis Brodie, the "Skidmore Craft Invitational" was designed to bring together a stylistic range of some of the best and most innovative of contemporary work. Having achieved this aim, the resulting exhibition was informative and exciting. The "metal" section of the exhibition, the largest of the three disciplines represented, contained 92 works by 25 artists, with work ranging from earrings to large, steel sculptures Artists with strong, established styles were sought for the exhibition; the result of this search was a selection of well-known metalsmiths whose work has been nationally exhibited.

Among the group of metal sculptures, Angry Warrior Under a Cloud of Knives and Meaned UP Man and Woman by Bruce Metcalf were stunning, dynamic examples of Metcalf's style Often the transition from jewelry, with its perfection and fine detail, to sculpture is an awkward one. Metcalf finds a way to make highly successful sculptures which still retain something of the goldsmith's orientation to media, technique, detail and surface texture. In these sculptures, the scale is still small enough, and the forms sufficiently complex, to justify the rich detail and often precious or preciously treated materials. The viewer is drawn by the drama and complexity of the forms. While the mood of Metcalf's sculptures is often angry and violent, there is also a joyous and Youthful exuberance.

Construction and I Wish I Had Known Herbert by Gary Griffin were tall, welded-steel sculptures, representing an almost complete departure from the small, polished world of goldsmithing. These powerful pieces, both about nine-feet high, still conveyed a certain feeling of fragility, with their very long, slightly tilting and graceful verticals. Appropriate to an artist with the training of a jeweler. Griffin has added to these works some very small objects, such as a hat, an arrow, a tiny fence, which are arranged upon a "landscape" within the sculpture. To someone outside the field of metalsmithing, however, the addition of these details might seem decorative or out-of-scale.

Louis Mueller's Rude Host and Venetian Mathematician, while relatively small in scale, belong to the category of contemporary sculpture, as opposed to metalsmithing Mueller's references to other works of art and to stylistic trends were thoughtful and abstract.

Triskelion and Mixed Metaphor, both by Carol Kumata, revealed yet another path taken by a metalsmith/sculptor. Both sculptures had a metaphorical subject, and in each the primary element was a pleasing, rather architectural metal (copper or bronze) form. In these particular works, the addition of paint and materials, such as wood or plastic—elements so often welcomed in contemporary metalsmithing—detracted rather than added to the finished sculpture. These somewhat garish and literal elements lessened the air of ambiguity and subtlety present in some of Kumata's other works.

Another departure from the traditional subject matter of jewelry or holloware were the more two dimensional works, or wall pieces. Wall Object by Robert Ebendorf was actually the result of a collaboration with photographer Francois Deschamps. Consisting of a three-dimensional object within a collage of photography and other materials, this work deals with photography, trompe-l'oeil and actual objects. The square object within Wall Object reflects unmistakably Ebendorf's style and his jewelry and is remarkable in its integration with the surrounding photographic elements. It is interesting that Ebendorf chose not to turn the small, three-dimensional object into a pin to be removed from the wall piece, a by now popular solution. Another mixed-media wall piece was Tale of Ise by Eugene and Hiroko Pijanowski. Within the work were actual pins which could be removed and worn. While this was a complex and subtle work with an intimate, participatory quality, it was not as cohesive as Wall Object.

Jamie Bennett's work was strikingly represented by both wall pieces and brooches, all involving framed enamels. The enamels, done in a restrained and expressionistic style with subdued palettes and matte surfaces were severely framed and reflected Bennett's deliberate choice to participate in this field as a primarily two-dimensional, painterly artist. One sensed in this very personal style a thoughful rejection of the decorative and of references to function or to preciousness. In contrast to Bennett's enamels, Martha Banyas's Terpsichore reveled in the brilliance and complexity of traditional Limoges enameling, while presenting her dynamic, representational imagery.

Holloware, that exacting discipline, was exhibited by a few very innovative artists. Helen Shirk's early holloware consisted of beautiful containers, full of complex sculptural juxtapositions, which may have seemed belabored, if only in the making. These recent containers were fresh, more simply constructed, with a focus on strong directional forms, combined with color obtained through rich patinas. Holloware Construction #4 by Susan Hamlet, a goblet shaped like an inverted cone, standing on angular legs, contained tiny geometric objects scattered along the cone's inner wall. There was a machined, impersonal quality to this work, and at the same time a mysterious intimacy in the small, contained objects which obscured the goblet's function. Robin Quigley's pewter Figurative Bowls I—III revealed abstracted faces reminiscent of Paul Klee's work and of tribal masks. The nails (hair) protruding from each bowl (which was actually a shallow platter) reinforced their primitive quality.

The greatest part of the "metal" exhibition consisted, appropriately, of jewelry, which ranged from the traditional to the innovative. Some works represented a continuation of an artist's established style (Reinhardt, Mawdsley, Harper, Lechtzin, Woell, Arentzen); others revealed new directions in the artist's oeuvre (Fisch Hu, Shirk).

William Harper's Archangel pendants and a series of brooches entitled Savage l—V gave breathtaking evidence of a personal style which is unaffected by current fashions and trends. Harper's work incorporated with assurance qualities which many artist/metalsmiths eschew: brilliantly rich enamels, highly precious materials, a certain decorative aspect, an extravagance, a thoughful attention to function. Encompassing these qualities is a powerful esthetic, laden with spiritual and fetish references.

A new direction was evident in three brooches by Eleanor Moty. These sculptural pieces incorporate tourmalinated-quartz, crystals and silver in small, effective, geometric objects. There is no separation between stone, setting and the rest of the piece, each brooch is a completely unified, abstract image. Bracelets by Mary Lee Hu also revealed stylistic changes in an established artist's work. Forms have been simplified and restrained, enabling the viewer to appreciate the flawless craftsmanship and pleasing combination of finely woven metal structures with smooth surfaces of silver and gold.

David Tisdale's anodized aluminum jewelry, characterized by solid masses of color and the layering of planes fastened together by simple, mechanical connections, had an immaculate, geometric grace. Whitney Boin's collection of gold earrings represented a different category of jewelry than the other work in the exhibition. Much more commercially oriented, it did not seem in keeping with the spirit of the exhibition. Edward de Large's Banana Torc, Banana Earrings and Classical Earrings, also production jewelry, were simply made, witty and artful. The Classical Earrings, an obvious yet delicately rendered pun, reminded one of an 18th-century architectural drawing.

The artists in the "Clay, Metal, Fiber" exhibition contributed, on the whole, work of a very high caliber. While certain stylistic connections were revealed among the three crafts, one was made aware of styles, trends and issues peculiar to each. In the fiber exhibit, one felt the strong influence of other two-dimensional disciplines, such as printmaking and painting. In the clay exhibit, I was struck by the diverse schools of thought that are the history of contemporary clay. Metalsmiths, often looked upon as the more tradition-bound group among the crafts, the group which was slower to change and innovate, slower to stretch the parameters of the craft, can no longer be classified in this manner. Just as the clay and fiber exhibitions showed great creative energy and diversity, so did the metal section. Since metalsmiths have more recently broken with more traditional concerns, such as the development of and preoccupation with technique, and with the conventions of jewelry and holloware, this display of such superior work was all the more exciting.

Stephen J. Albair: 9 LIVES and OTHER LIES . . . 1984

80 Washington Square East Galleries, New York City

July 5-20, 1984

by Pat Maggio

"Contextual sculpture" is Stephen Albair's way of describing his current work. Although a rather vague description, it is strikingly apropos when viewing the strange, story-telling scenes depicted in his sculpture/jewelry. In his latest show Albair moved beyond his early preoccupation with the "fashion" aspect of jewelry into a more serious genre that surpasses the implied obsolescence and disposability of fashion.

Not to worry—the work has taken on new complexity in fully developed ideas that were once only hinted at, but Albair has lost none of his sense of the absurd, and every new piece is sure to evoke at least a smile as he jokes with us and pokes fun at life.

Starting with a single image he layers ideas and information onto it, from xerographic drawings and photographs through to the final intricate sculpture/jewelry. When the wearer of a piece of Albair's jewelry reaches into the sculpture to remove it for wear, an entire history unfolds. The strong narrative quality of the image along with the supporting prints and sculpture give this history to the piece. In making the viewer aware of what jewelry can be, Albair successfully redefines the whole nature of jewelry.

9 LIVES and OTHER LIES . . . 1984, the title piece, is a small sculpture atop a 48″ base. The viewer's curiosity is aroused by a gold-plated brass screen that a cat (an engraved-brass found object) has just leaped from under. When the screen is removed all questions about the unusual imagery, created in part by another found object—a postcard, are answered, and once again Albair succeeds in amusing and teasing his audience. The woman standing behind the screen holds a removable tie tack/lapel pin in her hand and the gentleman in what seemed a questionable pose is found to be innocently repairing a sofa.

The piece was crafted of etched mirror plexiglass, to reflect the image back to the viewer, so the viewer becomes part of the image. The use of clear plexiglass allows the piece to be translucent eliminating any distinction between front and back. The gold-plated brass fixtures lend a jagged, fragmented textural element to the slickness of the rest of the piece. The incredible attention to detail shows evidence of the compulsive, bordering on the neurotic, but this only adds dimension as Albair simultaneously layers ideas and materials in ways never seen before.

The ambiguity of each piece leads one to the conclusion that the subject doesn't matter much. It could be this or that, depending on the viewer's experiences and prejudices. What matters is the freshness and candor of the vision. Albair has the unique ability to make us see the strange and the familiar at one time in his work and makes them complement and belong together—a very special talent.

The European Watch, Clock and Jewelry Exposition

Basel, Switzerland

April, 1984

by Etienne Perret

The European Watch, Clock and Jewelry Exposition is the world's largest and most sophisticated jewelry show. It is held in Basel, Switzerland every April, with 1,100 exhibitors showing their finest designs.

Both the quality of the jewelry and the types of display are far beyond the best of the American shows. Instead of flea-market-like open booths, the jewelers in Basel use rooms with a door that closes and display cases on the aisle. This makes the boothes like little stores or offices where one can conduct business more privately. Many of the exhibitors go to great lengths to make their displays more extravagant than those of their neighbors.

The method of doing business is also different from that of U.S. shows. In America buyers are always looking for new designs and something different. The buyers in Europe are more careful. Change happens more slowly, with buyers often waiting many years before going into a new line or look. But, on the other hand, when they do, they are willing to make a commitment to it and will probably stay with it longer.

Currently, there are only 12 American firms that exhibit at the show. Two firms are multinational companies with European offices and the other 10 participate in the U.S. Pavillion, organized by the Manufacturing Jewelers and Silversmiths of America (M.J.S.A.). The show administration has limited American participation to the space allocated to M.J.S.A., who chooses the exhibitors based on their quality and likelihood to succeed in the European market.

As a whole, the European Watch, Clock and Jewelry Exposition is not a place to go looking for innovative ideas. Instead, it is the sophistication and refinement of years of experience that makes the show so special.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Czech Jewelry Artistry: A Melting Pot of Art

Fourth Annual Selected University Metalsmiths

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Elisabeth Treskow: Pave Maker of Modernity

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.