Metalsmith ’86 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

29 Minute Read

This article showcases the various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1986 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features the Arline Fisch, Carolyn Morris Bach, Herman Hermsen, Marie Zimmerman, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

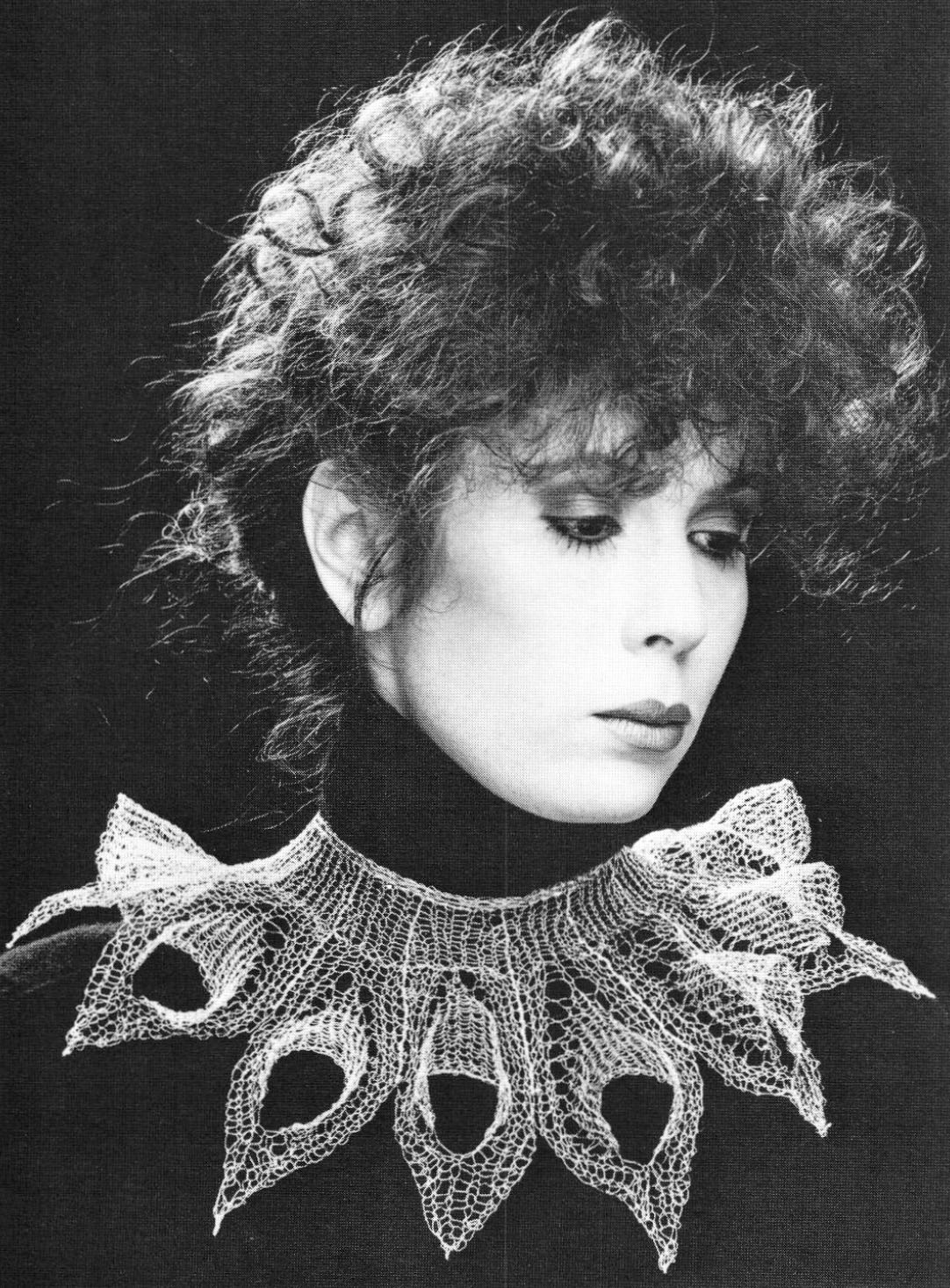

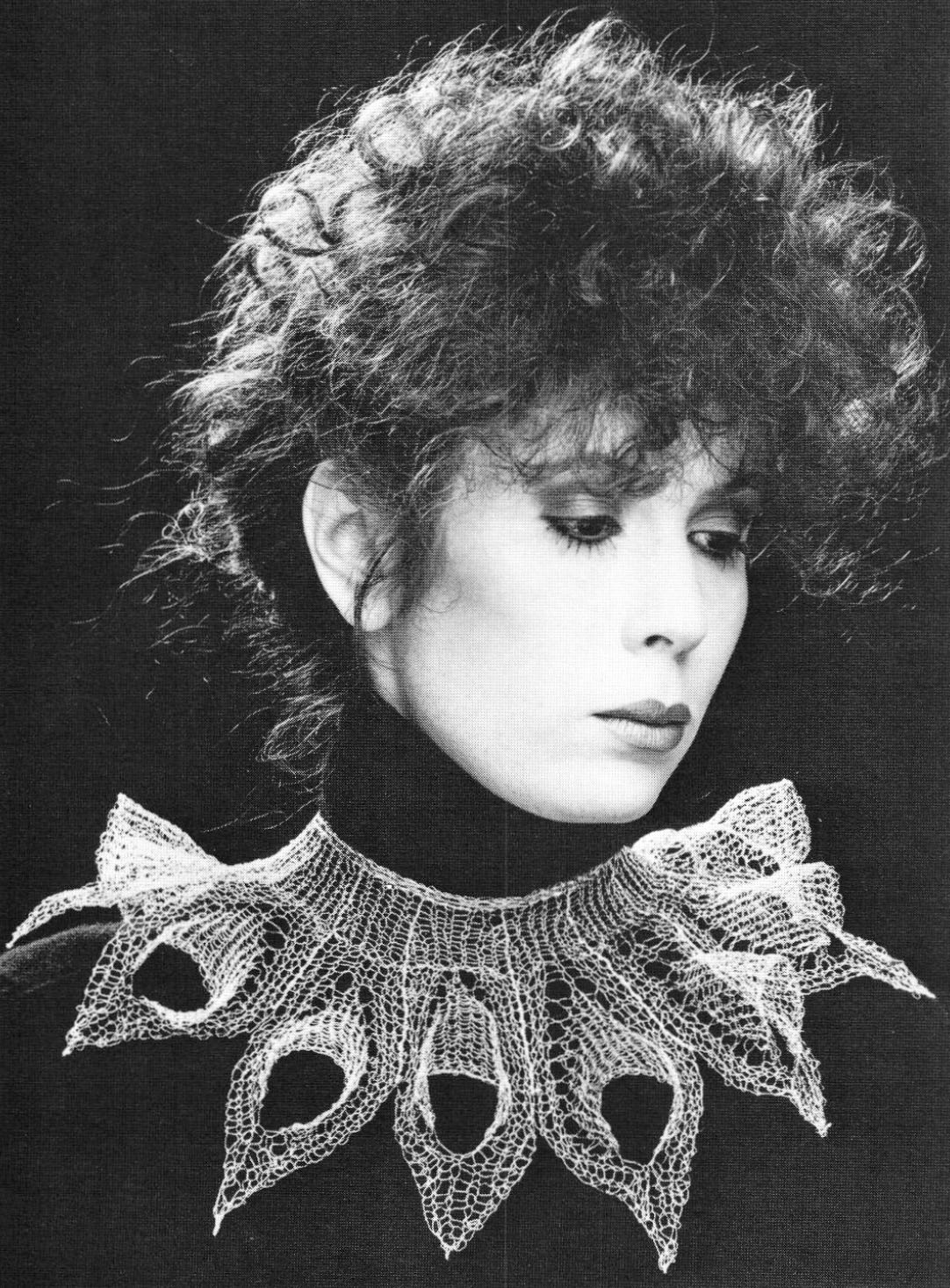

Arline Fisch

Helen Drutt Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

June 8-July 12, 1985

by Sharon Church

There is a sense of drama here. The gallery is dark, the room recedes, the cases glow. The work is colorful, large, suggestive of the body form and poised for the animation that adornment will bring. This is Arline Fisch's knitted-wire jewelry at the Helen Drutt Gallery, a group of work that is mature and highly resolved.

Though these knitted metal pieces refer to clothing, they extend beyond the process itself. The artist's knowledge of fiber structure and fabric has played an important role in the development of her jewelry forms. A neckpiece can be large and mantlelike, regal in domination of the upper torso; a bracelet can hug the body like a sock; and though the material is metal, it is also lacelike, flowing, supple and pliable. In definition, each piece seems to fall somewhere between jewelry and clothing. It is ornament that pays homage to the body light in weight, comfortable in fit, striking in color and form.

Fisch creates with wire a material that is at once metal and fabric. Using hand knit, spool-knit or machine-knit techniques, the artist produces a woven metal cloth that she can treat almost like thin-gauge sheet. She pushes and pulls and coaxes the fabric into various forms, a kind of extended metalworking. And while these forms will maintain their newly acquired shape, they will also retain the softness and responsiveness of cloth.

The structure and stretch of the knitted wire gives the work remarkable qualities. There is rarely a need for mechanism. The ornaments—belts, hats, necklaces, bracelets—pull on, stretching slightly, then relaxing to conform to the body or returning to shape. Often, the orientation of the piece is determined by its placement on the human form. Further, the structure of the knitted wire allows the artist to play with color. Through the use of coated copper wire, Fisch has found a sympathetic palette in bright orange and red, rich purple and green. By knitting two different color wires together as one strand, she creates a shimmering, iridescent effect. The rhythmic, repetitive nature of the knit pattern contributes to stripes and overlays. Close inspection reveals the artist's pleasure in manipulating these subtle rhythms through placement and detail.

Fisch uses one of three different knitting techniques in the production of each piece: hand, spool or machine. The choice of process contributes directly to the esthetics of the finished work. The machine-knit pieces seem to maintain greatest allegiance to a geometric configuration. Even though distorted through stretching and recombination, the rhythm and regularity of this material maintains predominance and lends overwhelming flavor to these single, strong pieces. In comparison, the hand-knit work is far more organic Frothy and foamy, the irregularities contribute to a more lacelike feeling through softer, more plantlike forms. Spool knitting seems to provide the artist with regularity in the overall form, though inconsistencies from stitch to stitch give these pieces a singular life. The three spool knit tubular necklaces are compelling in their simplicity. Silver and gold wires are knitted into hollow, transparent tubes that have an amazing strength in compression. The enlarged 18k section seems engorged with the richness of the material. In these neckpieces, aspects of machine- and hand-knit processes begin to converge. The simple tubes are obviously geometric in shape, yet they share in the organic quality of a Hawaiian floral lei.

The most recent work, and that pointing in new directions, evidences a pushing of the machine knit fabric even further. Fisch's manipulation of the material off the machine is opening up new possibilities Elizabethan ruffs and snakelike tendrils anticipate a more baroque feeling. Recognizing that this body of knitwear is but one aspect of Arline Flsch's total oeuvre, one is struck with the continued productive output of this artist in her ongoing search for innovative process and personal growth.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carolyn Morris Bach

Swan Galleries, Chestnut Hill, PA

May 4-31, 1985

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

September 16-October 21, 1985

by Jan Yager

There is something about metal that can really slow you down. It makes a casual, spontaneous approach just about impossible . . . unless you happen to be Carolyn Morris Bach. I am beginning to believe that she has found some metal the rest of us can't find, with a hardness on the Mohs' scale of paper pulp or clay. Her work consistently appears fresh, intuitive and malleable.

If you are familiar with Bach's work, it is likely to be her cosmetic brushes, they are beautiful, functional and irresistably appealing. What I know her best for is a fearless and prolific search for new forms, new challenges and unpredictable combinations. She may delve into the possibilities of large copper baskets casually formed and lead soldered, or gold and silver enro containers or brushes of all manner. Next she will be making tiny little bird nests or powerful fetishes, then long rambling necklaces sprinkled with nonmetal items. All breathe a facile control of the metal in what she terms a "natural, pre-industrial look."

Bach's latest body of work is a case in point. There is a full range of work: earrings, brushes, beaded and fetish necklaces and, the latest, vessels on stands all with a compelling sense of magic and mystery. She seems to have wholly absorbed and synthesized the essence and imperfect beauty of the primitive cultures she so deftly draws inspiration from.

Her necklaces are a variety of tiny and big, skinny and fat beads ending in clusters of coral, antique amber or fetish dolls which are often skirted or wrapped. All have the subtle layering and rich surfaces that define her mark. Often the pieces have or refer to actual or ritual uses. Gathering, containing, rites of fire are all suggested by her new vessels, which are seemingly meant to hold things, but perhaps secretly or with reverence. They are hung or set on three- and four-legged stands, much like twigs lashed together for a campfire. Some imply stories of horses, or have faint traces of horses inlaid in the surfaces. On one piece a little beast is frozen in motion above slashes of lines joining a middle sash to the rest of the piece. Twiglike handles jut out the sides, allowing the piece to rest on its stand or tilt open on a table independently.

She enjoys ornamenting her ornaments. A basket may have a belt of tiny clay beads and slivers of metal, a fetish necklace may have its own necklace or at least earrings. One motion adds to another. A shape or line is inlaid then repeated with chasing and overlay, or may simply be outlined with a colored pencil. If a piece should bend in an unexpected way she may leave it, should it tear she may patch it as though it were a pair of jeans. There is no attempt to hide process, no apologies, no hesitation. What is revealed is an urgency to get ideas out fast and flowing, confident that the message is there, the right answer, the first time.

Bach speaks of nourishment from many sources, including American Indian, Eskimo and African works. It is an eclectic yet very selective grouping, leading to a personal and original style.

I am always on a search for artists who surpass the medium the endless techniques and processes, the restraints of function, wearability, marketability, tradition. And when I catch myself hunting for that magic metal, I remind myself that what Carolyn Morris Bach really uses is an alchemy of intuition and the forge.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fifth Annual Selected University Metalsmiths

Norman R. Eppink Art Gallery, Emporia State University, KS

April 1-19, 1985

by Marjorie K. Schick

Seldom do audiences outside the locale of the university get to see both the work of professor and student, which together illuminates the strengths of the teacher as educator and as artist and the imagination and skill of upcoming metalsmiths. This idea provided the inspiration for the "Fifth Annual Selected University Metalsmiths Exhibition."

Following the precedent established by Gary Marsh, formerly teacher of Metals at ESU, this year's show featured the work of San Diego State University Professors Arline Fisch and Helen Shirk and their students, along with that of Associate Professor Marilyn Griewank da Silva and her students at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. The work of the faculty and that of the students was professional, inventive and varied. Yet the show was more than simply educational. The exhibition held the viewer's attention not only for the beauty and well-crafted nature of the work, but more importantly for the ideas and the individuality of the artists represented.

The show, consisting of 32 pieces, featured holloware, flatware, jewelry, and sculpture, done in materials ranging from silver and copper to anodized aluminum and titanium and combining plexiglass and Colorcore formica with various metals. There was also an obvious interest in heat-coloring metal and in chemical patination of metals. The variety of form and technique was dazzling. Each piece invited study and contemplation.

The works ranged from the elegant, hard-edged, angular Conical Neckpiece of silver and patinaed copper by Gina Westergard, SDSU, to the whimsical Ritual Dance of the Great Potato God by Lynn Johnson, BGSU. The latter, an assemblage of small figures holding chairs and a life-sized potato stuck with toothpicks, all painted an intense fuchsia and placed upon a boxlike base, painted aqua with freely sketched lines of hot pink and white, was a pleasant surprise in a metals show not only because of its playful nature, but also because of its color and juxtaposition of images.

The faculty contribution to this exhibition was outstanding, both for the drama of the work as well as its sensitivity of form. Professor Arline Fisch, well-known for her success in employing textile techniques, offered a red, machine-knitted necklace with a violet knitted overlay, which was beautiful not only for its form but also for its color relationship. Her Double Tube bracelet, sculpted of ridges of wide and narrow bands of knitted red wire, seemed much grander in scale than its actual size. Professor Helen Shirk's work also had a presence that made the form seem monumental. In her Vessel CVQ, overlapping planes of patinated copper rose elegantly from a small base and thrust themselves into space. The colors and patterns achieved through patination were rich in their contrasts, and Shirk's understanding of form is unparalleled.

Object l, a piece created of raised and fabricated copper, brass and sterling, by Professor Marilyn Griewank da Silva is so rich in details: notched edges, evenly spaced posts and a surprise of coiled red wires under an arched marriage of metals which forms the lid, that the viewer returns again and again to study it. The work, with its handsome proportion between the detailed lid and the fullness of the raised container, is also worth contemplation for its combination of colors, directional movement and contrast of detail played against large, smooth surfaces. The piece has a ritualistic quality, which is perhaps a reflection of Marilyn's recent stay in Korea as artist-in-residence at Kookmin University.

Inventiveness of form characterizes the entire show but most notable was SDSU student Thomas Seabury Brown's Cocktail Table for One. The anodized aluminum cup and grid were balanced so precariously near the edge of the marbleized "tabletop" that they gave a sense of visual tension to a piece alive with contrasting surfaces and patterns, Kristin Diener of BGSU offered in Winter Weeds: Five Hair/Sweater Pins and/or Tator Tot Spears a series of stickpins growing out of a plexiglass and wood base that were as playful to look at as the name implied. SDSU's Donna Stoner had a unique idea for her Participation Box/Neckpiece. She grouped magnetized elements that could be changed and rearranged to suit the wearer's fancy. Even the box with a fabricated sculpture on the lid could become a base for the display of the necklace or could serve to store the necklace parts.

Strong contrasts were evident in the works of other artists. Isabell Hund of SDSU played taut, arched steel wires over colorful textured, anodized aluminum oval shapes in a series of three bracelets. BGSU student Durelle Pefferman gave copper a surprising softness in her New Beginning, a raised copper bowl beautiful in its play of a soft rolled edge against the crisp formed contours in the body of the piece. By concentrating on the malleability of metal, Pefferman was able to give the rolled metal edge the appearance of leather or a substance of similar softness. At the other extreme, subtle coloring and measured lines gave BGSU student Nam-Woo Cho's enameled wall plaque, Changes, a highly controlled appearance.

The show as a whole was very impressive. The technical ability demonstrated by these students was excellent, and, more importantly, their ideas, ranging from SDSU student Asako Fuller's Epaulette Military Procession of silver combined with multiple foot and boot images cut from Colorcore formica to the pert liveliness of BGSU student Anya Firszt's sterling Cocoa Pot, were varied and imaginative. In all it was a professional and stimulating exhibition, valuable because of the diversity of ideas presented as well as the high quality of the craftsmanship.

Not only should the teachers and students of the two schools represented be applauded for the skill and imagination shown by the work sent, Emporia State University should also be complimented for continuing to provide this opportunity for students and faculty from institutions across the country to exhibit together. The beneficiaries of an exhibition like this are not only the viewers but also the participants. I look forward to seeing next year's show.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Three German Jewelers

Elaine Potter Gallery, San Francisco, CA

July 2-27, 1985

by Carrie Adell

Reviewers often make broad generalizations. My aim is to use as few second-hand references as possible in discussing the jewelry at The Elaine Potter Gallery in San Francisco. Once again, we must thank Ann Grundler for facilitating this exhibition, bringing to the United States the work of Wilhelm Buchert, Bernd Munsteiner and Klaus Ullrich.

Cultural prejudice (a form of pre-judging) is difficult to avoid. There is a temptation to compare the efforts of these three individuals on the basis of some common attributes: of origin, of content or imagery, of technique, of intention. Another approach might place the art works in a historical perspective, comparing them with work of another time or place. Does the experience of art (or other labeled esthetic event) need a historical perspective? Isn't the experiencing of an object about intrinsic qualities and not accumulated lore? I can experience the individual piece (its heft, texture, design) or I can experience accumulated lore about the piece (values, beliefs, myths, judgments). Better still, I can have both, provided I don't allow the "lore" to influence my own gut-level feelings.

The jewelry of Klaus Ullrich embodies the processes, both mental and physical, of its creation. Three chokers, among the rings, brooches, earrings and bracelets, were most appealing to me. In each choker I could follow (infer) Ullrich's problem-solving activity. Each of these chokers is composed of small geometric modules, repeated regularly their full length, each terminating in a clasp of the same apparent module, so well concealed, it was difficult to find which unit was the clasp. A link-on-link chain has each lump ring of 18k wire enclose a spindle shape of oxydized silver, like two coolie hats, point to point, and perpendicular to the jump ring's plane. The rings also join each other perpendicularly. The chain thus exhibits the spindle shape as a full circle from head on and as a very skinny H-shape from the edge, as well as all the variations in between when the wearer moves. A denser look is achieved in a choker of wedge-folded rectangular units of oxidized silver sheet. Each wedge points into the open end of the preceding wedge. The folded end is tipped on each corner by a tiny gold ball, restrained by each circle of flattened 18k wire attached to the flared end of the wedge. The resulting choker is supple and snakey, an almost elastic configuration. The story of Ullrich's concept and process is embodied within. Most of Ullrich's work communicates to me his awareness of structure, of motion, his processes of creation and fabrication. His visual statements are strong and confident. His forms are analytical yet playful, inventive in concept, crisp yet gentle in execution.

Both Klaus Ullrich and Wilhelm Buchert employ geometric forms to express their ideas: Ullrich's are statements about articulation and movement, Buchert celebrates the relationship between linear and planar surfaces. Several of Buchert's necklaces were constructed with chains of burnished platinum wire in linked lengths, clad in shorter lengths of softly textured 22k gold tubing. The alternation of these metals creates an interrupted line of reflected lights and glints in the chain. In some the surface pattern of the pendant is itself made of a laminated sheet of alternating gold and platinum stripes, domed and sandblasted, and set as round cabochon beneath a sapphire cabochon. The center line of three parallel wires is composed of alternating bands of gold and platinum. These lines lead the eye downward from the point where the chain meets the drop, at a grouping of three diamonds. The triangular center diamond is an arrow directing the viewer to the pendant. Buchert's work is largely symmetrical, or almost so. The visual message is one of serenity, of calmness, of repose. There are no unresolved diagonals to leave the eye's mind incomplete, in a state of tension. Even Buchert's use of gemstones contributes to the sense of order. They are elements of the total design and not focal points per se.

In marked contrast to the sense of repose generated in viewing Buchert's work, I found the works of Bernd Munsteiner to be like tightly condensed packets of energy Munsteiner is a gem cutter and goldsmith whose skills are mutually enhancing. His gems are not cut and polished in traditional cabochons or standard facets. They are individually sculptured to the fancy of the designer and integrated with the various metal environments. Especially in his rings, perhaps because of their compactness, Munsteiner achieves a wonderful integration of gemstone and metal. He cuts opposing, stepped, parallel grooves on facing surfaces of a tourmaline crystal and continues the grooves into the body of the ring, in a contrasting metal, platinum, inset in 18k gold. Transparent and polished surfaces are juxtaposed with opaque. Subtle transitions of color tones develop inside the gem and in the metals beneath and around it. The recurrence of the parallel step cuts the gem and metal of many of the jewels suggests wrappings, or even restraints, visually imposed on Munsteiner's designs. These cuts occur on the transparent material: citrine, aquamarine, amethyst, indicating to me Munsteiner's (unconscious?) caution and restraint in handling such traditionally precious materials. It is in the jewels with "semiprecious" agates that he really lets go. A brooch, ring and two pairs of earrings incorporate carved and sandblasted agate as their major visual statement. The metal settings are reiterations of the natural and enhanced patterns in the agate. Working within these patterns, Munsteiner terraces into the agate, revealing the variations in hue and echoing in reverse the process of its generation. Through these pieces I got the sense of the human behind the objects, assessing, making decisions, transforming a concept into a visual and tactile experience.

I have attempted to bring the reader something of my experience of this exhibit. Ten other reviewers would give you 10 different viewpoints, equally valid. I know some things about art, and yet I also know what I like.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Herman Hermsen

V.O. Galerie, Washington, D.C.

June, 1985

by Gretchen Raber

At this show, Herman Hermsen, from the Netherlands, laid out the images of a jewelry philosophy. It was marvelous to behold stacks of brightly lacquered strips or wire shapes that folded and angled in complex variations. All are based on the geometry of circles and squares. The concept of measured divisions of circumferences used tangent lines to form bends and implied planes. Hermsen is very concerned with the development of concepts of simple form to create what he calls "High Expression."

The resultant objects are also made for wearability in the manner which he as an industrial designer might view the human form. That is, if one were to see the body as a mannequin of simplified geometric volumes. Hermsen moves from this premise to contrast body form with the geometry of decoration. His work is constructivist in the sense that he seeks to integrate simple technological solutions with abstracted autonomous forms. His work falls into groups of logically, continuously metamorphosed perimeters. Whether in gold or aluminum, they retain the premise: all designs are minimalist.

One particularly interesting group of brooches caught small amounts of fabric in the center bow of wire, just as camping tents hold a volume of fabric stretched inside the external frames.

Other series of neckpieces, bracelets, brooches and rings, all based on sections and planes of a circle, are elegant forms when seen as groups. It is then that the relationships of the variations are most evident. Primary colors accent the curved strips adding a playful and humorous quality.

Most provocative are Hermsen's headpieces. Essentially wire rectangles, they break stiffly across the ears and create a bar in front of the face. Herman demo-ed it for me (Definitely, not for the meek.) In fact, those pieces and several others generated some fairly candid comments from Egon Kuhn, a reviewer in the 1984 catalogue, "Werk Herman Hermsen."

". . . (T)he problem of wearability arises . . . Indeed there are people on whom such a necklace looks harmonically. But on others it looks like an inflexible apparatus. Whoever tries to put the blame of this on appearances loses sight of the fact that the harmonical or disturbing effect is not due to the necklace itself. It is much more the physical and psychological condition which comes to light here. . . . The head jewellery pieces have the same effect but much more extreme . . . (They are) immediately regarded as aggressive and unpleasant when being worn." That viewpoint certainly demands a great deal from the wearer.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Reflections: A Tribute to Alma Eikerman

A Retrospective Exhibition of the Jewelry and Metalsmithing of Alma Eikerman and Forty Indiana University Alumni Metal-Artists

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN

July 10-October 6, 1985

by Gail Farris-Larson

Vital, large in scale and aggressive in design are adjectives that would describe the immediate visual impact of the retrospective of Alma Eikerman and 40 of her past students from Indiana University. The Indiana University Art Museum opened this premier exhibition with hundreds in attendance, among them alumni from all over the world.

The exhibition dealt explicitly with the title, a "tribute" to Alma Eikerman and was a reflection of three decades of metalsmithing at I.U. The retrospective span offered the viewer a unique and distinctive insight into the brilliant sense of design and strong understanding of form reflected in the sensibilities of both Eikerman and her students. This visually commanding collection of metalwork was historically significant within the overall context of metalsmithing in that it recorded the distinguished contributions of one artist and the impact of her work, life and teaching.

Alma Eikerman has not only the inventiveness to continue her search for new forms but also the courage to reexamine the refinement of her earlier experiments. From her first piece done in 1940 to her current work, the 99 pieces shown traced the strong currents of her esthetic. The development of energetic lines and planes, contrast in textures and the use of bulbous forms all combine to make bold, sculptural constructions for which she is well-known.

The alumni participants were invited to send their older as well as newer pieces. making a total exhibit of 300 works. The large number of older pieces had a curious and surprising effect: they dominated the entire exhibit with their presence and large scale. The exhibition induced both a nostalgia for old influences and associations and a feeling of renewed stimulation.

I have heard frequently the curious comment among metalsmiths that "smithing is dead." This exhibit was an affirmation to the contrary; smithing is decidedly alive and vital. Evidence of this appeared in the number and size of pieces throughout the show that utilized smithing techniques, the frequent incorporation of smithed parts in a piece and the diversity and range of concepts explored. To experience these pieces was really to perceive the unique understanding of form that these artists possess as a result of their strong smithing background.

Indiana University is synonymous with smithing, especially experimental smithed forms. Coffee Server with Lid by Susan Ewing and Coffee and Tea Service by Lynda LaRoche were two outstanding examples of exceptional design fused with appropriate functional objectives. Marjorie Schick's Container with Rubber Hose was breathtaking with its clean, sweeping lines and dynamic sculptural and spatial considerations, coupled with an inquisitive use of rubber hose as a contrasting element. Richard Bauer's Double Bowl embodied the concept "less is more" by seducing the viewer to explore the edges of the bowl, rather than the interior. Sibylle Ulsamer's Bottle Form with Square Opening was an appealing combination of the sphere and the cube.

The newer work revealed the diverse directions and multi-levels of development of each artist represented. A lively interest in experimental forms prevailed not only in metal, but in the use of nontraditional materials A particularly outstanding example of invention and freshness was the linear wooden stick form Necklace by Marjorie Schick Series Arquitectonia ll: Tile Ring; Screen Ring; Frame Ring by Susan Ewing and Not a Word Spoken—Too Old by Kathy Buszkiewicz presented fascinating combinations of metals with other materials. The bracelet and brooch forms of Helen Shirk were exquisite.

If there was a disappointment in the show, it was that some of the "premier" pieces by alumni were not presented, such as Marjorie Schick's highly experimental smithed piece made under Eikerman's Carnegie Grant, Helen Shirk's early smithed pieces, the work of Leslie Leupp, who chose not to participate, or a more complete representation of Jacqueline Fossée's work. Perhaps in a moment of nostalgia, only fellow participants would know or care. But despite this, the exhibition was a timely and judicious survey, particularly for metalsmiths of all generations. One was keenly aware of the thread of continuity that exists in the design sensibilities the group presented as a whole. This is clearly attributed to our association with a dedicated and loving professor whose experimental approach to technique and design was the inspiration that directed our inquiries to bold new heights and enthusiasm.

A fully illustrated black-and-white catalog is available from Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN 47405.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Reactive Metals

Brookfield Craft Center Gallery, Brookfield, CT

June 2-August 4, 1985

Brookfield/SoNo Craft Complex,

South Norwalk, CT

August 15-October 13, 1985

by Harriet Brisson

At first, when entering the Brookfield Craft Center in South Norwalk, the "Reactive Metals" show curated by Ivy Ross looked dazzling, stunning in its rich display of colored metals. But it quickly became too flashy in the application of high-tech processes to trivial ideas. Much of the work was an ostentacious display of technical finesse. Color had not been used to advantage. Technique was dominant.

The color possibilities of reactive metals can be very exciting, but most of the exhibitors used it in the same way, without subtlety or purpose. The successful pieces were good because of cohesive ideas, not seductive color. An excellent example of this was Candace Beardslee's Black Hat, broad-brimmed with holes punched through it, displayed on a mannequin head with a black stocking stretched over it. Unfortunately, it was placed on such a low base that one had to get down on ones knees to see it. Her work ranged from a brightly colored little pin to a silver and black Tie to the Black Hat. The Tie was Dada in concept with hinges that allowed it to bend into three planes as though it were draped cloth. Was she poking fun at all the other serious works in reactive metal?

Perhaps the best piece in the show was a bracelet by Brigid O'Hanrahan. This ½" thick and ¾" wide circle of gold-colored metal was understated in its use of color yet strong in its delicate tracery of silver on the outer surface. Her nine pins, arranged in three rows of three to form a square functioned best as a single piece of small sculpture, rather than individual pins, due to the interrelationship of abstract patterns.

The small pin by Ivy Ross, composed of subtle color on horizontal and vertical rods in a dull, gold-colored frame, approximately 2″ x 2″, stood out among the other work in its showcase as a little gem. David Tisdale's pair of purple earrings were strong in their geometric design, so well integrated with their evocative color. His pin shown with the earrings did not have the same presence due to its awkward relationship of forms and its scale.

Dean Smith's pins were compelling in their minimalism. Each was a single tightly twisted wire, like an electric element curving three dimensionally, that straightened out to turn into a fastener. They are the product of a truly creative approach to reactive metal in their design and monochromatic utility. However, in being hung from a string, freely floating in space against the confusing background of the gallery, they easily could have been overlooked by the casual viewer.

Vernon Reed used the potential of color produced by reactive metals to make images on his work. Two pins, You Win and The Wall were strong social and political statements. Their color was critical to the portrayal of the concept expressed by graphic means on a metal surface, According to his resume, Reed is a self-taught artist with a bachelor's degree in psychology. Perhaps this accounts for his not being seduced by the technical process and thus able to use it to its fullest advantage.

The metalworker remains a craftsman as long as media and technique dictate the resulting work. Those artists discussed here transcended process and produced pieces that well qualified them to be called art. Unfortunately, they were in the minority in this exhibit. Equally unfortunate was the low-budget hanging.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Marie Zimmerman: Art and Craft in Metal

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

July 2-September 8, 1985

by Kathleen Nugent Mangan

American design in the early years of the 20th century was characterized by a multiplicity of styles, among them an eclectic revivalism inspired by a vast spectrum of sources. Styles from Europe, the Orient and the American Colonial past were well known, and the work of leading designers reflected these diverse points of inspiration. Rarely were such pieces accurate duplications of the historical works which had inspired their creation. Instead, their assimilation of disparate styles and techniques produced something uniquely American and contemporary.

With "Marie Zimmerman: Art and Craft in Metal," the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented the work of a notable exponent of this revivalism. Widely exhibited and recognized in her own time, Marie Zimmerman is largely unfamiliar to contemporary audiences. This exhibition of 16 objects demonstrated her skilled use of varied materials and techniques and confirmed her contribution to American design.

Marie Zimmerman was born in Brooklyn in 1879. She studied metalwork, painting and sculpture at the Art Students League (1897-1901) and Pratt Institute (1901-1903). In 1901 , she became a member of the National Arts Club, Gramercy Park, where she later opened a studio. Zimmerman pursued an active career into the 1930s, producing a range of objects from jewelry, flatware and tea sets to furniture and architectural ornaments. Her works were exhibited nationally, and one of her pieces was acquired by the Metropolitan in 1922.

In the recent exhibition, primary focus was on the container form. Zimmerman was shown working with copper, silver, gold, iron, brass, ivory and precious stones; her designs drew inspiration from nature and from sources as diverse as Chinese, Celtic and Persian traditions. A covered box of Chinese style represented refined simplicity in its classic, timeless form. Only a carved jade finial decorated its richly patinated copper surface. A bowl of hammered silver illustrated Celtic influence skillfully abstracted horses recalling the fantastic animals of Celtic art formed its base. A "Persian" box combined ivory, gilt silver, semiprecious stones and pearls. Its cover of floral petals, pearls and stones lifted to reveal four delicate miniatures framed in ornate doorways between columns.

Naturalistic elements were also reflected in Zimmerman's designs. A silver "leaf" bowl with fine, delicate ivy "growing" across its surface represented this direction in her work. A silver tureen on an organically inspired iron base further illustrated Zimmerman's close observations of nature and her absorption of Oriental traditions in its repoussé decoration. The Metropolitan's piece, a silver flask with a lade top and crystal finial, was decorated in elegant restraint by garlands of gold and rubies.

This small collection of work was enough to reaffirm Marie Zimmerman's place as an important American metalsmith. Clearly, she was both a masterful technician and an artist very much of her time. Her works provide a significant illustration of a major direction in early 20th century American design. I left the exhibition only wishing to see more by this long overlooked artist.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Colored Gemstone Jewelry Design and Repair

The Enamelware of Sean Alton

Bladed Sargasso Server by Andy Cooperman

Naum Slutzky Jewelry at the Bauhaus

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.