Metalsmith ’87 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

37 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1987 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Charles Lewton-Brain, ASF Gallery, Wichita Art Association, Jewelry Design Resource, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Charles Lewton-Brain: Recent Work

Anna Leonowens Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia

July 15-26, 1986

by Stephanie Menard

Charles Lewton-Brain's show, a selection of 56 pieces executed over the last two years is an exploration of "preciousness" in the modern technological world.

Lewton-Brain works in layers, layers of surface bursting through or scraped away, unfolding or receding. Layers of thought unfold as one moves through the show: pieces refer back to other pieces, enhancing various aspects of his vision. It is the violence of a seed pushing up through the ground that counterbalances the packaged propaganda of consumerist violence. This is our heritage and our tradition: the ancient and the new, the sterile and the unearthed humanity and machine. Lewton-Brain exploits solid yet interchangeable elements, pushing and exploring dimensions. As the formal elements change in the pieces, the ideas behind them serve to launch the imagination onto other tangents and a new wealth of ideas.

The focal point of one sculpture s four folded copper discs, which can be programmed" to respond with a great deal of control while remaining organic. Lewton-Brain turns these discs, shaped with basic tools. into ancient amulets, precious for their age and mystery, removed from the value of newness and function. The piece is reminiscent of an early telescope, its lenses hanging from machined bolts, that can be shifted along a girder. It becomes a structure for focusing on human nature, but one which is myopic, rendering the humanistic side of life as an artifact of technology.

This sense of technology as a culminating effect of the machine-age esthetic and its accompanying loss of humanness also manifests itself in a series of brooches that are supported by an intricate network of girders lifting the center of interest off the body. For Lewton-Brain, our allegiance to the new lakes us further away from the body, the symbol of humanism. In the Radar pieces, as in the brooches, this dilemma is communicated through fabrication techniques. The back structure is based on strong images of 19th-century engineering. The front with its dish form can be manipulated to change direction and sits elevated off the base, making the piece appear to float, no longer a part of the body. Nature has been interrupted by technology, the engineering, while intriguing and intricate, serves as wedge and support between body and object. As we have distanced ourselves from the precious object, so, too, we have moved closer to the alien machine.

It is not just a grim vision of the world that Lewton-Brain offers but the ability to gain a new perspective from continually referring back to humanist foundations—the first tool, the artifact of our own creative ability, the source of preciousness. His show further examines another social view—that we live in a society that will do anything for a buck. And this buck has no regard for humanity beyond turning it into manipulated statistics.

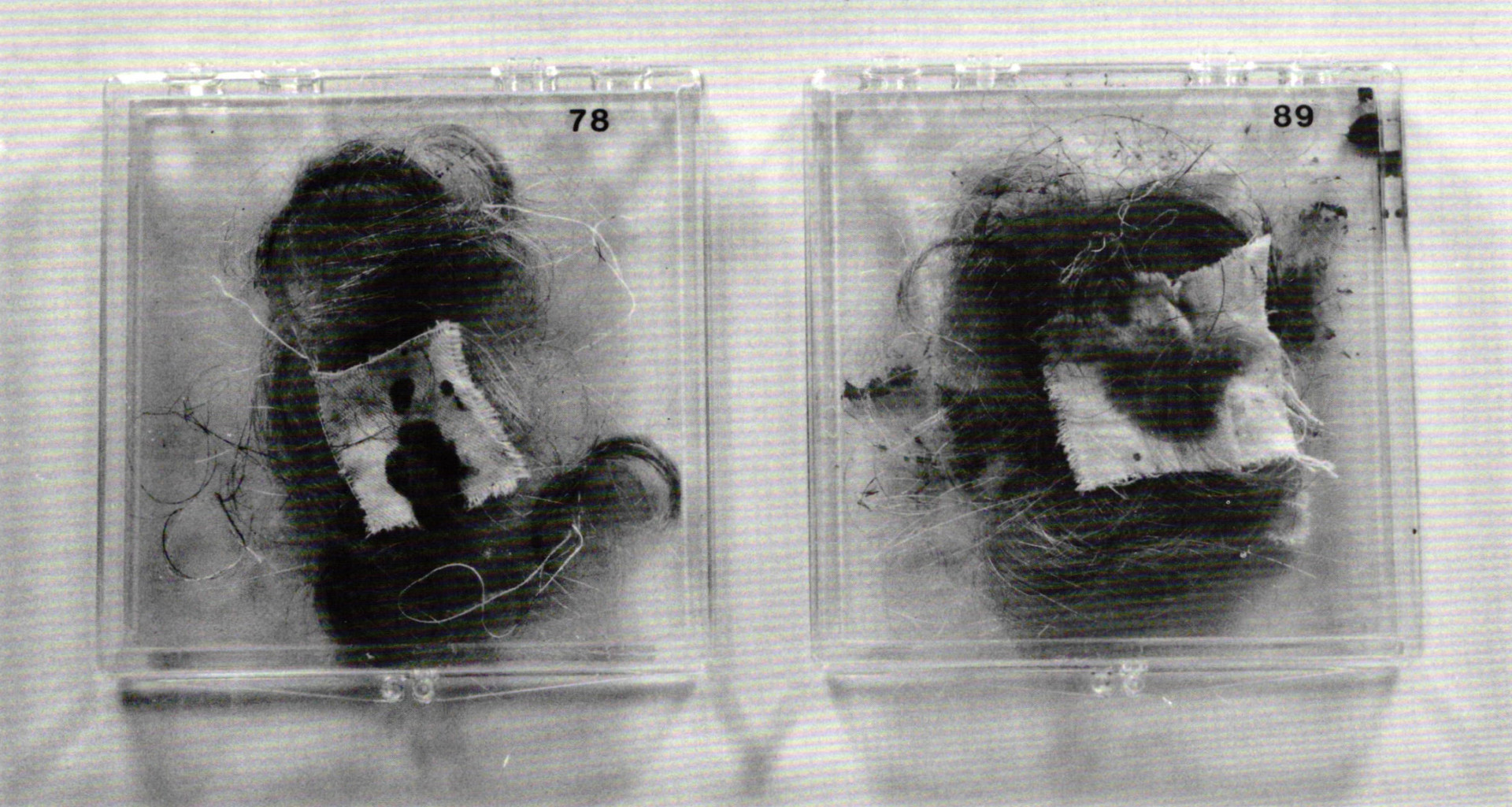

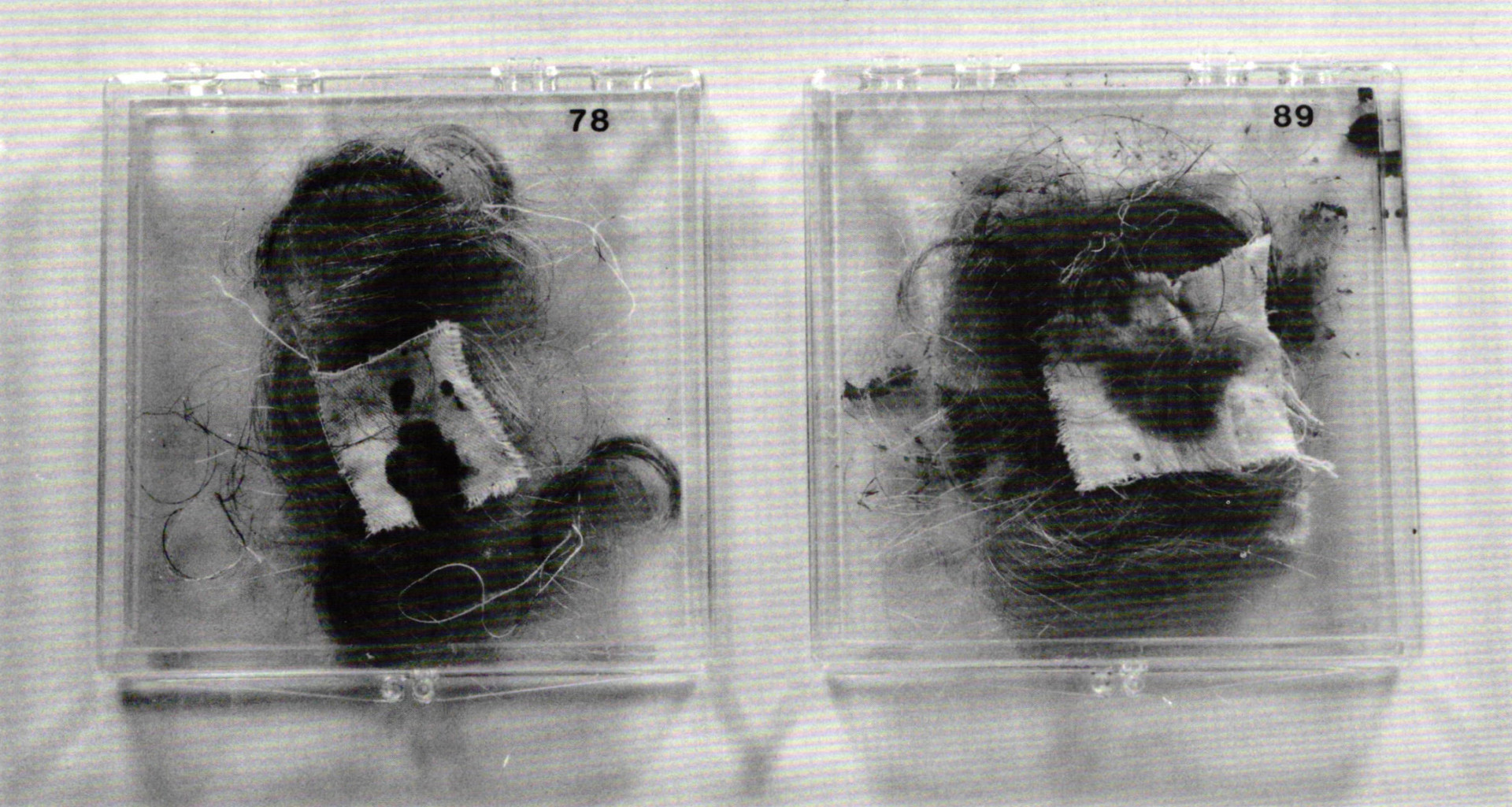

This view is expounded in Selling the Culture, two wall pieces or culture boxes filled with gauze, red paint, hair and blood. It is confrontational jewelry, designed to lure the viewer then shock him into examining the ideas inherent in the pieces. The painted pins are graphically more interesting than those done with blood, but their real strength lies in their connection with Icarus 6, a drawing that portrays Icarus pitched against the horizon line, the red paint like accidental smears across the paper. Icarus dared to tempt a fate chosen for him, although the endeavor to fly on wings of wax was doomed. His destiny did not lie in that direction, even though he sought to change it. The futility of his gesture lay in his death. The link to the Culture pieces seems to be that despite the Western notion that we control technology, technology controls us.

The grid in these pieces is representative of Western culture, predicated upon control and prediction of natural statistics. The gauze is a parody of the grid. Manipulated within the culture boxes, it symbolizes our self-manipulation within the culture. This is not finger pointing, since Lewton-Brain includes himself in this vision—his hair, his blood. He is playing with context and meaning, cultural acceptance of commercialized violence is accepted culture. And the culture that we, like Icarus, tend to cultivate becomes the propaganda of consumerism. lf it can be sold, it can be justified. The joke is on us. It is a participatory piece, with artist as producer, viewer as consumer.

Lewton-Brain often injects a note of serendipity into his work. He does not control the nature of the piece from the outset but allows it to change as it develops. The decision to use real blood in Selling the Culture: The Real Thing stemmed from accidentally cutting his hand.

He is interested in letting the nature of his work, his brand of humanism counteract the transforming powers of the machine culture so prevalent in today's society. It is the surface aged with patina and scraped away to reveal hidden surfaces that is the link, however tenuous, to the ancient humanist mode. He is true to the ancient goldsmith tradition of excellent technique. He believes in tradition.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Designs for the Body: New Norwegian Jewelry

ASF Gallery, The American-Scandinavian Foundation, New York City

September 23-November 21, 1986

by Vanessa S. Lynn

Why should an exhibition of young Norwegian jewelers be heralded and shown at the American Scandinavian Gallery in New York City? Why should this reviewer be spending time thinking and writing about the work exhibited, and why should Metalsmith be taking up limited review space with those ruminations? The answer is exposure; not for the artists but for the viewers.

The show in question was put together by Heidi Sand, a former student of SUNY New Paltz professor Robert Ebendorf. She and 12 other young jewelers received enough funding to concurrently show bodies of work at the Clodagh, Ross and Williams space in New York City's East Village and Washington's VO Galerie, in addition to the above. There was a press kit, a press opening and a mini-catalog. Ten of the 12 artists made the trip over here. To lend weight to the venture, Tone Vigeland and her work turned up in New York at the ASF show. But, while Vigeland's work is wonderful, it is too mature, too advanced to be shown with the work of these younger artists. She has been neither mentor nor inspiration to the others; she simply shares their homeland. Her work was out of context, a context that in this case was one of development and formulation—these artists have mastered their craft but, for the most part, are still looking for their individual voices.

The participating artists and a sketch of their dominant methods: Tove Becken: crisp, graceful curves of black PVC with silver, niobium steel and titanium fastening accents; Millie Behrens: smooth, circular strands of colored nylon with silver structural supports for neckpieces and an armring; Liv Blavarp: laminated patterned blocks of wood, carved and sanded into simple forms, Christine Bongard: spare, circular arm rings and neckpieces in aluminum with linear black on black surface embellishment; Sigurd Bronger: a variety of materials (brass, steel, paper, gold, silver, ping-pong balls), which balance light, geometric, closed forms on linear supports; Gry Eide: colored cane, newspaper and wood in circular forms (bangles and neckpieces); Ingjerd Hanevold: mesh collars, and pleated niobium sheets formed into earrings and bracelets; Morten Kleppan: black, acrylic incised sheets fabricated into smooth, ameboid shapes with colored, geometric additions; Ingrid Larsen: long, linear bamboo pins with horizontal fiber accents: Laila Irene Olsen: sharp-edged, perforated metallic pillow forms as beads for necklaces and earrings; Heidi Sand: a variety of functions (armpieces, earrings, ear pins) and materials (silver, copper, aluminum, formica, ebony, rubber) utilizing the triangle (or cone) in suspension; Ann-Rita Bryghaug Wold: chiseled, organically shaped marble forms on thin, black, steel structures.

If this abbreviated description serves any purpose, it is to allow the reader to glean certain common points. Clearly, these artists share an interest in exploring nonprecious materials in an overwhelmingly geometric format. There was no interest in the narrative as subject. When the writer adds that for the most part these artists took much pride in refined workmanship, one can surmise, given that the group is European, that these works as a whole had the unmistakeable hallmarks of Bauhaus-influenced training.

That is the case. In fact, with one exception, all attended the National School of Art and Design in Oslo in the late 70s. Sigurd Bronger was educated at Schoonhoven in the Netherlands. Hence, it is not surprising to feel the influence of such artists as Caroline Broadhead (UK), Gijs Bakker (Holland), Paul Derrez (Holland), Therese Hilbert (West Germany) or Herman Hermsen (Holland). Theirs is a valued and visible tradition.

Several artists deserve special mention. Morten Kleppan's four-inch black ameboid brooches were refreshingly original. By incising the black acrylic surfaces and including primary color accents on the interior of the adjoined forms, he successfully manages to humanize his inherently cool material and evolve a form that is simultaneously playful and serious.

Gry Eide's use of vibrantly colored cane to create bangles and neckpieces was also a successful utilization of material. She draws her ideas from a combination of primitive adornment and urban imagery. Her threatening, spiked bangles are connotatively diffused by the fact that those daggers are made of shocking pink, yellow, orange and apple green toothpicks.

Heidi Sand continues the pointed formal vocabulary she explored while studying and working in this country (1984-85). She, too, investigates the "jewelry as weapon" esthetic. She has lived in New York City.

So, the work provided little in the way of revelation. It showed young Norwegians, who set up studios following their formal educations in the late 70s and early 80s, working in the mode of what we have come to call the International Style. For anyone following the field, it was well worth experiencing. Views of current international work are too few and far between. We tend to get the opportunity to see the work of the Tone Vigelands of our discipline presented at a mature point in their development. We are left to piece together through the dearth of information, where they came from and how they arrived. Being given the opportunity to viewer younger work, allows us to evaluate the work of artists, both European and North American trained, from a broadened base of experience.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

20th Century Design

Jewelry Design Resource, FlT, New York City

November 15, 1986

by Tim McCreight

The Jewelry Design Resource of the Fashion Institute of Technology held its fourth symposium "20th Century Design" at the school's Manhattan campus and drew an estimated 650 to 700 people. Speakers included Peter Hinks, Graham Hughes, Fritz Falk, Paloma Picasso, John Loring, Evelyne Posseme, Robert Lee Morris and Wendy Ramshaw.

Though precise demographics are not available, the audience appeared to be a broad spectrum of jewelry professionals and enthusiasts. This diverse mix poses a challenge for a one-day symposium, just as it is a challenge to the success of organizations such as the Society of North American Goldsmiths, the Manufacturing Jewelers and Silversmiths Association and others.

Peter Hinks of Great Britain did a fine job at maneuvering this tricky slalom, providing an enlightening and entertaining overview of major trends in jewelry over the past 80 years. Graham Hughes, another British jewelry critic and author, spoke on "Intrinsic Versus Artistic Values in Modern Jewels." This is a vital concern of contemporary jewelry and could have been a highlight of the day. Hughes's many years of involvement with designers, museum curators and jewelry manufacturers place him in a unique position to discuss the issue, but unfortunately we did not hear his thoughts on this topic.

This intrinsic/artistic dilemma is a phenomenon inherent to jewelry. The materials of other disciplines—clay, marble, canvas, paint and so on—might have been scarce in the past, but I don't think they ever had what we would call intrinsic value. Maybe there are lessons in history that can inform us today; I was disappointed that Hughes did not focus his remarks more precisely in this direction.

Perhaps it is exactly the intrinsic value of our materials that is our problem. It is nothing novel to point out that a painting gains in value as it is praised by critics and collectors. Each of the major art fields (painting, sculpture, printmaking, etc.) has developed a substructure of criticism and connoisseurship. In the field of jewelry, this role has been usurped by the pawnbroker, weighing a piece and assessing its value.

On one level this has accounted for the proletarian growth of jewelry. Even small towns have a jewelry store, while many cities cannot sustain an art gallery. The fortifying belief has always been that "gold lasts." lf the going gets rough, you can always cash in Grandma's silver, and of course that continues to be true. Unfortunately, the point that has gotton lost over the years is that design also "lasts." Without the stamp of approval by museums and auction houses, art jewelry has little hope of finding the audience it deserves.

The designer and entrepreneur Robert Lee Morris spoke, as it were, from the trenches. He described his personal history and the evolution that has created three galleries in New York City, three in Japan and one in Europe. His enthusiasm and apparent success speak for themselves. Feeling a need for an unusual fashion-conscious presentation of art jewelry, Morris engineered a one-person campaign, and thus has made an important mark on the jewelry scene. His efforts at identifying and fostering designers rather than materials set an important precedent, creating a model for other gallery owners to follow.

The English jeweler Wendy Ramshaw has also set a standard, in her own way. By marketing herself and her work in the United States through exhibitions and speaking engagements, she exemplifies the artist as advocate. Like many other contemporary jewelers, such as Bob Ebendorf, Mary Lee Hu, Michael Good, William Harper, she asserts her right to be evaluated as any other artist. These people and many others like them are bringing their work to the attention of the fine art community.

If Robert Lee Morris and Wendy Ramshaw may be described as generals in the field, at this symposium we also heard from the high command. Dr. Fritz Falk of the Pforzheim Museum, along with Graham Hughes, former director of Goldsmith's Hall, represent important leaders in the fine arts world. Both are active supporters of jewelry and the enthusiasm of each man is beyond question. I look to these people and their colleagues around the world to help build the scholarly foundation needed in the crafts. It would seem that a symposium such as this one would be an ideal place to forge a manifesto of contemporary jewelry esthetics. It was disappointing, then, that little of substance came from this camp.

The Jewelry Design Resource and FIT are to be congratulated on continued efforts in this direction, I hope that each subsequent symposium builds on the last, establishing a mature and supportive audience. Just as SNAG has enlarged its embrace to include European and Oriental influences, I hope that future symposia will give American talent their due and possibly encourage a new generation of jewelry critics and writers.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Twice Gifted

The Gallery at Workbench

November 13-December 22, 1986

by Akiko Busch

In recognition of the fertile exchange between art, design and craft mediums, the Gallery at Workbench sponsored an exhibit to promote collaborations between woodworkers and metalsmiths. Such collaborations are, of course, nothing new. Woodworkers have traditionally looked to metalsmiths for fixtures, decorative accents, sculptural drawer pulls, etc. Predictably, several pieces in the exhibit acknowledged and continued this tradition; a glass-top table by Jim Fawcett and Rob Sperber with brass and steel fixtures was a conventional exercise in which the one was "applied" to the other.

The exhibit became more noteworthy, however, when craftsmen went beyond such traditions, in pieces that integrated more fully the two materials and mediums. Materials were disguised: a hat rack by Bob Ebendorf and Jerry Kott offered provocative play with surface treatment. The dark stain on the wood structure suggested that it might actually be wrought iron; affixed to the rack were beads wrapped in Japanese newspaper, glitter, glass and stones. Two pieces by Judy Kensley McKie and Jonathan Bonner also focused on surface and texture. The mahogany body of Arizona had been painted and polished in a milk paint to coppery sheen, while the base of Chive Head was stained a deep green to evoke a surface patina. Wood and metal playfully impersonated one another.

But it was not simply material impersonation that distinguished the most successful pieces. The strongest pieces in the exhibit were those in which materials were fully integrated. Such was the case in White Bottle and Black Bottle by Jamie Bennett and Alphonse Mattia. A precious quality emanated from the small shelf carved in each vessel. One contained a small cup; the other, a tiny, anthropomorphic chair. Bennett's fragile gold foil and enamelwork rendered Mattia's vessels receptacles of a different sort, midget altars for eccentric treasures, But the pieces were themselves delicate landscapes; it was not simply the application of fine enameling that made them so. Mattia's wood tiles are as precious as Bennett's enamel work. Here, material does not dictate value.

The collaborations were most successful when the integration of two materials was achieved, when metal and wood were fused in a single object with a single idea rather than being materials applied to one another in prescribed functions. This show suggests how the confines of traditional collaboration might be removed, to be replaced by a more unified esthetic, which is, of course, the whole point of collaboration.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Belle and Roger Kuhn

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

September, 1986

by Gretchen Raber

Collaboration at its best s a seamless application of esthetic and technical considerations. The permutations of these endeavors, whether intramedia or intermedia, should result in harmonic counterpoint. As in a marriage, to which artistic collaboration surely can be compared, the partners to be successful must find commonality. Vastly divergent esthetics premise a conflict that only strength of ego and physical fortitude can overcome in hope of a creative discovery.

The new jewelry of Belle and Roger Kuhn at Plum Gallery was categorically collaboration at its best. Ironically, among the factors that contributed to this success was the Kuhns' accommodation of media constraints. Belle and Roger split the execution not the esthetic. They have no set work pattern. Initially, Belle did the enamel, predetermining the final form. This evolved into prior design consultation with Roger.

The recent open metal-frame pieces are examples of designing metal and enamel before initiating work. This more collaborative effort parallels Roger's solo explorations in metal.

In the Kuhn's newest work, geometric shapes are truncated. The implied sections are realized by Roger's metal lines or Belle's planar enamel. Thus negative space expands the design field to fabric color and texture as the brooch or necklace is worn. This also makes for lighter wearability for larger brooches a serious consideration in enamels.

Apart from their intellectual approach, the Kuhns have a carefully researched understanding of technique. Enamel has physical contraints imposed by its chemistry. This is especially critical with Belle's stripe patterning. Keeping the designs simple allows greater focus on color. One series was the illusion of folded paper. These "windows" of metal and enamel are derived from design studies based on paper folded back on itself so that the image appears to be floating.

The most intense work in the show was a stunning group of brooches incorporating pattern on pattern. Belle introduces microscopic, black and white, check shapes reminiscent of Japanese fabric. This pushes the technical limits of Belle's thin-milled, steel-wire, roller-embossed silver foil. The layering of this foil causes problems with adhesion and warpage. A thin, contoured, linear design creates the additional problem of a greater silver area surrounding the enamel troughs. This results in an increased possibility of a chemical reation between the metal and the physical properties of the colors. This complication is further affected by the color range when working with silver. Reds, oranges and pure yellow become muddy in transparent application. The Kuhns, however push the color parameters of the blues and greens, which evolve into combinations of transparencies and opaques of vibrancy. Pattern on pattern is keyed to color pick up, which, unfortunately, black-and white photographs negate in large measure.

In all their series, Belle and Roger evidence their consummate mastery in an interchange based on excellence and respect.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Spectrum

October 3-31, 1986

Lubbock Fine Arts Center, Lubbock, TX

Christina Smith

Department of Art, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX

by Elizabeth Skidmore Sasser

Like the marriage of metals, "Spectrum," an exhibition of the work of five metalsmiths, was neatly bonded with the guest appearance of metalworker/jewelry designer Christina Smith as lecturer and critic at Texas Tech's Art Department. The invitational show sponsored by the Fine Arts Center displayed metal pieces by Martha Glowacki (Madison, WI), Leslie Leupp (Lubbock, TX), Mac McCall (Oakland, CA), Tom Muir (Detroit, Ml), and Robin Quigley (Providence, RI). Abstraction, western regionalism laced with humor and elements of ceremonialism produced variety and vitality in the jewelry designs and in the sculptures, which ranged from miniature pieces to the thrust of a theatrically scaled torch constructed by Glowacki.

Labeled Untitled Sculpture, the torch had a core of carved wood with the surface plated with textured and patinated copper. A chalice at the top of the handle was circled by grasslike wires. Looking into the heart of the cup, the viewer discovered carved and gilded terraces descending to a small herm, or omphalos, planted in the midst of wiry flames. Unfortunately, the piece suffered from its relation to a dull brown display unit. In positioning it, there was a call for action, even the radical gesture of tossing the flambeau into a corner as one would a discarded firebrand. Glowacki's jewelry also contained hints of magic. A red baton dropped on the brooch called Grass Dance invoked energies which might have been released in a prehistoric ritual.

In marked contrast to the Dionysian fervor of Glowacki's metal constructions, Robin Quigley drew upon a restrained historicism. Quigley has described her brooches and necklaces as "classical pieces" with origins that may be "traced far back in history." A particularly satisfying necklace by the artist was fashioned with elongated pewter beads lightly marked on the surface with a delicate calligraphy that appeared to have been rubbed with graphite.

A linear emphasis was dominant in Tom Muir's Three Figures. Spare as a trio of praying mantis, the multimedia sculptures brought together brass, nickel, steel, aluminum and sterling silver. The geometry of positive parts defined negative space in the way in which Japanese brushwork embraces the paper. Lamps designed by Muir illustrated the multifaceted fields open to metalsmiths; however, the constructions posed an unresolved conflict between form and function. One bare light bulb demanded "shades" for the eyes; in the case of another lamp, a puzzle revolved around the process for removing a burned-out light bulb and replacing it without dismantling the whole structure.

The problem of disengaging wearable items from tableaux, each called Window Rock, was the challenge offered by Mac McCall. In Seduced by Clichés, a technical tour de force, a scenic romp in a world of Lilliputian billboard art was assembled. On the billboard, a mirage of the Painted Desert with a cowboy planted in the foreground shimmered in holographic realism. A favorite symbol of the artist, a zigzag signifying snake or water, slithered across the top of the sign. Placed in front of the hologram, a table supported an array of diminutive objects including an arrow-shaped rock pierced by a spear, while a tiny bronze deer stared at the cowhand—the hunted haunting the hunter. The table legs and the supports for the billboard with its scorching landscape were anchored on a metal surface painted to resemble water from which shark's fins ominously projected. Seduced by the artist into his world of miniaturization, the spectator was left clinging to that final cliché, "between the 'hot place' and the deep blue sea," while the only means of escape was a precarious arrangement of l-beams reaching toward uncertainty.

Leslie Leupp's bracelets offered "life savers"—stunning circles and combinations of squares in bold colors and amusing textures. If Kandinsky in his Bauhaus years had turned to jewelry design, he might have created a similar geometry of precision and joy. In stating his aims, Leupp noted that his work was "about color, its intellectual and emotional provocation. . . about dimension . . . about spirit." A rewarding aspect of Leupp's designs was the attention given to the mounting made to add a new dimension to each bracelet when it was removed and left on the dressing table. The interconnection between the wrist piece and its base resulted in a sculptural presence that is usually only associated with three-dimensional art of monumental size.

The jewelry of Christina Smith exhibited at the Texas Tech University Art Department presented a different aspect of the subject matter interesting some metalsmiths. Her bracelets and brooches with attachments of missiles, satellites, submarines and bombshelter signs would place the wearer at the center of cocktail parties, art openings or political demonstrations. The serenely designed weaponry was awesome in technical finesse, amusing in its unexpected context and guaranteed to initiate dialogues on the controversial subjects plaguing Planet Earth. Smith explained that her work "is autobiographical . . . the places I have lived, my friends . . . . My pieces are also often political and reflect the 'evening news.'"

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Earl Pardon

November 6-29, 1986

Aaron Faber Gallery, New York City

by Anlonia H. Schwed

Earl Pardon's solo exhibit consisted of about a hundred pieces of jewelry, installed in a handsome display by Angela Conty. It was an important exhibit, since Pardon is a master American goldsmith, heralded as such for the past 35 years. In addition to his jewelry, his teaching activities have had a broad influence in the world of metalsmithing. He is currently Professor of Art at Skidmore College.

On entering Aaron Faber's upstairs gallery, I was struck by the aura of elegant, controlled design that seemed to radiate from the collection as a whole. There was a sophisticated, gleaming array of bracelets, necklaces, rings, brooches and earrings, most decorated with intricate designs involving small circles, stripes, triangles. In each case, the varied shapes were disciplined into a beautifully balanced relationship. The delicate, small abstract decorations on the jewelry, frequently combined with bezel-set gems and small geometric areas of colorful enamel made me think of Piet Mondrian.

As I began to examine the work, item by item and close up, I was able to admire the tremendous skill involved in each piece. Indeed, I think the dramatic impact of the work derives from Pardon's execution. I felt no emotional involvement with the actual designs. They are completely intellectual, yet there is feeling in the work, and I think this comes from the superb execution. I could almost sense the concerned relationship Pardon has with each small part, each technical difficulty, each flash of color and gleaming piece of gold.

I particularly noted a brooch of silver and purpleheart wood, inlaid with gold circles and set with a beautiful amethyst. It was a wonderful mixture of media. I was also drawn to a silver bracelet in which some sections were inlaid with tiny stripes of ivory and ebony, others with enamels, some with bezel-set gems and still others with small geometric gold forms soldered on. All of these differing elements combined to form a lovely, unified work. A domed enamel ring, departing somewhat from the rest of the work because of the free-flowing cloisonné design, contrasted pleasingly with the surrounding pieces. There were several pieces with background metal surfaces that had been exquisitely textured with gold and silver dust.

A fantastic silver necklace formed of sections decorated alternately with gold, enamel, paua shell, rubies, sapphires, aqua, amethyst and garnet, all so cleverly interrelated was a richly harmonious work. I might observe here that the gallery refers to his work as "intricate collages in precious metal and gemstones that can be worn."

A gold brooch was delightful to the eye. I looked upon it as a "pick-up-sticks" masterpiece, an astutely arranged, soldered, random little heap of tiny golden sticks, each one knobbed at both ends. Another brooch, one of Pardon's newest creations, was not only a splendid design but of special interest because it involved his unusual technique for bringing out the pure metal in the karat gold and sterling silver—his way of burning out every impurity so that the resultant metal looks wonderfully precious and tarnish free.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fine Art Jewelry in America

Cross Creek Gallery, Malibu, CA

November 1-30, 1986

by Carolyn Novin

Jewelry exerts its greatest power when the maker objectifies an idea and communicates it to the wearer. This personal element, often sacrificed to the rules of the commercial fine jewelry esthetic, is an ingredient of more worth than gemstones or metals. Commercial concerns did not compromise Cross Creek Gallery's elegant show. With 168 works of one-of-a-kind and limited-production jewelry, it demonstrated that precious materials and sensitivity to personal design can coexist.

Caroline Strieb's care for surface detail and use of direct techniques encouraged a spontaneous, intuitive response to her Pod and Crystals bracelet. The combined units of sterling silver with reticulated globular areas, strips of gold overlay and bezel-set tourmalines suggested volume and depth. In contrast, Line Logic bracelet by Daniel Jocz was assembled with cubes and pyramids constructed of married sterling silver and 18-karat gold. While volumetric, it exuded an almost machined coolness. Lynda La Roche and Tony Papp also showed work in married metals.

Though most of the color in this exhibition came from the presence of gemstones, the use of other materials was noteworthy. Earl Pardon's necklace of 19 individually constructed "jewels" was a complex of glowing enamels with ebony, ivory, shell, gemstones, gold and silver; its impact was heightened by an appreciation for Pardon's personal selection of elements and his skill and inventiveness in assembling them. Rebekah Laskin's muted enamel palette and subtle explorations of depth were shown in several brooches and pins. Cheri Epstein's enamels extended her Iceberg necklace visually and structurally, enhancing the intricacies of the tourmalated quartz.

Wit and humor, while not abundant, were present in Charlie Buck's Parade necklace/- bracelet of onyx beads with whimsical sterling silver forms. Harold O'Connor made playful reference to fiber techniques, currently popular in jewelry, with rings featuring a large moonstone held by fabricated gold "twine." Christina Smith's bracelets, bold in size and powerful because of their direct narrative elements, were the most figurative works in the show and unique in their frequent combination of sterling silver and acrylic. Claudia Kuehnl was one of several artists to use architectural form as a basis for design. Her necklace. The Rialto was a miniature facade, meticulously fabricated in 18-karat gold and onyx, jeweled with a paradoxical coupling of cubic zirconium and diamonds.

There was no undercutting of the value of gems in James Barker's work. Earrings gleamed with richness of textured 18-karat gold sprinkled with sapphires, a ruby, an emerald or sometimes a turquoise, but always with a diamond. Barker, along with Eric Russell and Michael Norman Bayes, showed asymmetrical earrings, a welcome departure from traditional compositions.

Diamonds were used in a third of the pieces in this show. A cluster of them seemed to extrude from Yves Kamioner's 18-karat gold ring. Pat Flynn joined a single diamond with an opal, steel, gold and sterling silver in a small, wonderfully complex brooch. The visual qualities and connotative values of each element were amplified as each was viewed in the context of the others: questions of preciousness, fragility, permanence, industry and luxury came to mind. Flynn's brooch was an outstanding realization of jewelry's potential to stretch thought beyond the stimulus of an esthetically pleasing object.

Other contributors to this huge show were Bruce Anderson, Zbigniew Chojnacki, Kris Clark, Robert Ebendorf, Vicki Eisenfeld, Arlyn Fishkin, Nelson Giesecke, Michael Heintz, Mary Lee Hu, Kyle Leister, Randy Long, Barbara Mail, Pepi, Jan Sigrid Peterson, Ann Quisty, lvy Ross, Larry Seegars and Jan Yager. The varied work was colorful, beautiful and wearable. Within a conservative framework of forms and components, the assertive individuality of each artist provoked thoughtful comparison of contrasting personal expression.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Peter Skubic,

VO Galerie, Washington D.C.

June 6-July 4, 1986

by Nick Ward

"Halfway" is the title of this first U.S. exhibition of Yugoslav-born, now West German-based metalsmith, Peter Skubic. Originating in Vienna at the Galerie Graben this exhibition had toured several European countries, before coming to the VO Galerie. The show celebrates the artist's 50th birthday, hence the title, a personal note of optimism for his future.

The thing that strikes you about Skubic's work is that it encourages speculation on its form, content and purpose. The majority of works are stainless steel pieces, rigorously precise in their rectangular or cubic design. Although his work is wearable, it cannot be considered solely in the context of jewelry as body decoration. Few concessions to the traditional concept of small, precious objects as personal adornment are made in these works. They do have a spare, sleek and technological beauty, a stark contrast to the body, that can enhance the relationship between wearer and object. Catalog and documentary photographs attest to this fact. However, their primary intention is not to flatter the wearer or display technical bravado. Skubic's work must be approached as one would consider any good nonrepresentational sculpture; with an inquiring and open mind.

Technique, while ingenious and highly skilled, is subtly downplayed. His constructions, bisymmetrically arranged, generally open in form, and cagelike, are held together by pins, springs and other nonsoldered devices. This tension/compression system is not at first obvious, mainly because of the visual balance achieved in each piece. On close inspection slight variations of alignment between separate parts reveal the physical forces at work within the sculptures.

Skubic's three-dimensional source material appears to come from the visible effects of our late-20th century industrialized environment. Their forms allude to electric-wire pylons, high-line cables, power stations, coalmine winding gear, pit-shaft structures and cages, most of which employ principles of real or hidden tension in their operation. He does not literally copy these forms but borrows the essence of what orders and defines them as structures. Scale, too, is effectively translated, as the proportions of the work's individual component parts related to the whole makes even the smallest piece appear imposing.

Certain questions do arise. Is his work a strict acceptance of the industrialized environment? Is it a condemnation of our blighted landscape that causes the angularity, and austerely precise machine look, of these pieces to have a somewhat menacing quality about them?

Other works in this exhibition did not display such cool aggressiveness in their design. Long stainless steel pins, bowed under tension, had a rather organic, sinuous quality. A functionless, clockworklike piece, about 6″ high with steel pulleys and brass wheels, appeared to mock its own mechanical inefficiency.

In much of his work he is testing the spectator's view of what formally constitutes jewelry. A quite mysterious ring has large chariot wheels on either side, each missing a quarter segment from its rim. When worn or turned on a surface the entire ring gyrates freely. Most intriguing, though, is the ring's center piece, not a stone or crystal, but a miniature brass treasure chest containing a sealed object. The wearer/spectator is asked to imagine a fantasy piece of jewelry within this casket.

An illustrated catalog is available from VO Galerie, 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington D.C. 20006.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A Show of Vessels: Duncan Miller, Claire Sanford

Pacchetto Gallery of American Artistry, Newton Centre, MA

September, 1986

by Jill Slosburg

Duncan Miller appears at ease with traditional metalsmithing techniques—especially raising, inlay and construction—and equally well-versed in design, most noticeably post modern architecture. His precisely crafted, colored bowls are the right size for use, but they don't suggest function. In one untitled bowl, the outside form is defined by a linear framework with menacing funnel shapes that flow into the center, joining inside and outside. Many bowls seem to be inflated, testifying to the magical process of raising. Although the motifs are hard-edged and geometric, Miller's series is surprisingly sensuous. The bowls' round, taut skins are often perforated, exposing dark interior spaces. The geometric openings on these soft forms produce a curiously ordered violation of the bowls' surfaces. Unfortunately, the perforations reveal a wall so thin that it reminds one of how the vessel was made, destroying some of the mystery of the interior.

Claire Sanford's tall, patinated, cylindrical vases have a fragile, airy presence, almost intuitive in execution. Only the edges indicate that these green, powdery, opaque vessels are made from metal. Sanford approaches her work from a Cubist perspective, working in a planar way, often fracturing her cylinders and decorating them abstractly. Fin, nearly two-feet tall, is a poetic, volumetric collage. The work is spacious and meditative, inviting the viewer to ponder its meaning. Individual pieces are elegant, but the series offers little variation from one piece to another. Although the vase form lends itself to a variety of interpretations, ultimately it seems gratuitous. These pieces, which are too large and top-heavy to be used, have the last vestiges of functionality in the form of meager openings that appear at the top. I find them unnecessary, as the work is decidedly sculptural.

Miller and Sanford are bringing sculptural issues to metalsmithing. Their work is a celebration of personal vision and craft, but in some ways, it is flawed by a derivative form-building. Traditional ceramic vases and bowls seem to be their primary sources. I accept these forms in clay, knowing that they are at least partially generated by throwing and hand-building processes, but in metal the borrowed forms are less successful. In both artists' pieces, the thinness of the stock used to create the vessel betrays the apparent mass and scale of the work. I suspect, too, that the size of both Sanford's and Miller's works would be different if they weren't thinking about bowls and vases. I also question the reason for the intimation-yet-denial of functionality. There is a conflict between pure sculpture and functionality in their pieces, and in a profound way, the meaning of the work is diluted by this collision. Miller and Sanford raise once again old questions about form and function.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Wichita National All Media Crafts Exhibit

Wichita Art Association, Wichita, KS

September 7-October 5, 1986

by Christine F. Paulsen

The Wichita Art Association opened its galleries to the prestigious national juried craft exhibition of 250 works by artists and craftsmen front 40 states. Juror Helen W. Drutt English, Professor of Art at Moore College of Art, stated that the exhibition serves as a continuing force for the artists and encourages the study and exhibition of crafts. Works ranged in size from 1½-inch fabricated brooch to a powerful 10-foot, totemic, welded-steel and copper structure. In between was wide variety of shapes, materials and media.

Two of the three "Best of Show in All Categories" were awarded to works in metal, while second place went to Joan Ward Summers' tapestry T42, with its strong colors and bold surrealistic designs. First place awarded to Cycladic Figure with His Hair in a Roller by Thomas Muir. His stylized silver coffee pot with anodized aluminum squares reflects concern with craftsmanship and an interest in smooth, sleek, reflective metals. Third place was awarded for a group of three brooches created by Susan Mahlstedt. All three are fabricated holloware shadowboxes, one in copper and two in sterling silver. The small architectonic brooches have tiny recessed areas of painted enamel, which create an element of surprise and delight.

Jewelry, as always, commands a lot of interest by patrons and exhibitors alike, and there were many fine examples. Another example was the beautiful classical piece created in 18k gold by Ann Garrett. The spiculum-constructed Pavé Diamond Necklace is highly polished and hinged in sections so that it is flexible and conforms to the shape of the neck. The smooth, flowing lines of this necklace are in sharp contrast to the chunky, square, although smooth, brushed-silver necklace by Daniel Jocz. The hollow links with gold inlay are also hinged to allow for contouring of the neck, and both works demonstrate a meticulous concern with construction.

Richard Mawdsley, another artist working in 18k gold, created an exotic necklace resembling a ceremonial headdress. An elongated tantilium post, topped by a repoussé gold face with fabricated conical links and curved wires, forms the intricate and flexible necklace. This is an exciting work, requiring an infinite knowledge and understanding of the properties of the material.

Earl Krentzin's Robot Box and Monkey box also made a strong statement, even though his fabricated pieces are only four-inches high. These brushed-silver forms have numerous shapes and designs fused and riveted to the surface. To these whimsical pieces, he added semiprecious stones and placed his little characters on bases of malachite and onyx.

The swing from the small-scale objects to large-scale work allows for a focus on a variety of art-oriented approaches. One such approach is that of Richard L. Stauffer's innovative 10-foot-high sculpture Peasant Revolution, constructed of steel and found objects, wrapped with copper wire and copper tubing. At the base are round, painted, shieldlike objects, which add to the mystical quality and reflect a strong, primitive, totemic imagery.

Another impressive piece was Thomas Crossnoe's pewter Bottle, which won a Purchase Award for the Permanent Collection. In this large vessel, 24 inches in diameter and 18 inches high, the indentations of the hammermarks give an elegant shimmering effect to the surface skin. An inverted shell completes the lid and small cabochons of turquoise catch the eye.

David Luck exhibited two pieces Spire 2 and Spire 3. The constructed copper and brass pyramidal shapes are tightly controlled. Repetitive textural effects were created with wires, rivets, repoussé, dye-formed convex shapes and punched areas that looked like strainers. On the other hand, Helen Shirk's Vessel CV285 was elegant in its simplicity of design and form. Strips of copper painted black and carefully placed at slight angles were interwoven with colorful triangular areas to form a graceful oval bowl shape. This strong work is accentuated by simplicity of form and flat black color.

A flawless ability and thorough understanding of the materials are strong proponents in the functional forms of Memory Container by M. Avigail Upin and the Tea Service by Michael and Maureen Banner. Upin's brushed silver with gold inlays is a tightly controlled abstract design, The curvilinear shape is juxtaposed with sharp geometric forms, creating an asymmetrical design. The Banners' tea service is elegant and stylized. The graceful shape of the pieces as well as the sleek, highly polished surfaces create a sensuousness in sharp contrast with the dark wooden handles. With the increasing cost of precious metals, it is impressive to see large pieces created in silver.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Made in the USA 2017

Stuart Devlin Retrospective Exhibition

Metalsmith ’94 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

Master Metalsmith Svetozar Radakovich

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.