Metalsmith ’87 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

45 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1987 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features the American Craft Museum, Yurakucho Seibu Art Forum, Plum Gallery, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

American Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical

American Craft Museum, NYC

October 26, 1986-March 22, 1987

by Michael Dunas

To speak of craft today is to open a Pandora's Box of conflicting ideologies. Entranced with art versus craft, craft versus design, craft versus decorative art, our critical eye rarely focuses on the institutions and organizations that define the craft community and codify its official image.

For the past 25 years, the public persona of craft has been synonymous with the American Craft Council and its armatures the American Craft Museum and American Craft Enterprises. In its uncontested position as spokesman for craft, the Council has been able to meander through history, complacently assuming the support of craftsman and collector alike without need to defend its leadership role.

With all the ballyhoo over the new museum space and the colorful panorama of its inaugural show, it might appear niggardly to scrutinize the Council's intentions. But for a museum to remain a trustworthy representative of its nominal constituency, it must remain relevant to the goals of that community in both its educational and curatorial efforts.

Much has been written about this year's craft extravaganza, and the attentive reader can pick his way through a journalistic muddle of praise, bewilderment and befuddlement in the writings of Neal Benezra and Grace Glueck in The New York Times or John Perrault in the Village Voice. I have chosen rather to read the accompanying catalog and official press releases, since they lend considerable insight into a philosophy and ideology that heralds the "poetry of the physical."

Paul Smith, director of the museum, opens his prefatory essay forthrightly by telling us that craft by its very nature represents a unity of hand and spirit that reaffirms the human element in daily life. In the modern world it is our master craftsmen who achieve beauty which speaks for the creative spirit undimmed by the machine or mass media. Smith's idea of craft in society seems not to have evolved beyond Morris and Ruskin's socialist reformation, the last hope of a dying humanism guarding against the cold clinical machine age, an intractable idea that has been languishing for more than a century now. But why poetry of the physical? Smith in an interview that accompanied the show's press release claims that "we wanted to honor the process of creating craft objects. I am talking about the intrinsic physical qualities of the various media and the process by which the artist works with them." With the spotlight on craft as humanistic materialism, can religious revivalism be far behind? A society born again of craft?

But it is the "today" in the title that anticipates the new, that has us eager to relive the memories of "Objects USA," the 1969 survey upon whose glories and critical praise the current exhibit hopes to capitalize. The 300 objects chosen for the "Poetry of the Physical" were made in the 1980s and thus must be viewed as representative of our times. Smith, in his essay, paints a background for these works that evinces the curatorial perspective of their selection: "The 1980s represent a period of refinement rather than of experimentation for its own sake. While tied to its rich historical roots of function, craft today is distinguished by the sophistication level of its aesthetic. The aesthetic which evolves from the process of making and the artist's spiritual involvement with the material enables the contemporary craftsman to transcend traditional forms and techniques, creating works of genuinely new significance . . . With technique resolved, the central concern is to make an object as beautifully and as well as possible but also to develop its expressive possibilities . . . Beauty is not always associated with contemporary art, yet it continues to be honored in the crafts." I feel compelled to quote Smith here to dispel any charges of incredulity in my claims that his "idea of craft" is at best sophomoric. His claims about refinement, function, process, spiritual involvement with material and the delusions of beauty are belied by the works in the show. Either Smith had found that the diverse nature of the work needed a binding context or there lurks an ulterior motive behind the superstructure of his illusionary perspective.

When Smith looks back, and he must look back to 1969 and "Objects USA" as the last major survey mounted by the ACM, he struggles to find recognizable features that have altered the look of the craft community over the last 15 years. He comes up with seven: flexibility and growth of educational programs, careerism, expanded market resources, plurality of purpose, diversity of American culture, rapid technical evolution and the influence of design in manufacture. As we listen to Smith, it becomes increasingly clear that the "idea of craft" is bound by the goals of the Council, that craft history must be used to validate the existence of the Council and that the ulterior motive is the aggrandizement of the Council's long history of market dominance.

Now, what's good for craft is good for the Council is a safe bet, but what's good for the Council might not be what's good for craft. Considering the early endeavors of Aileen Webb and America House to establish a market for well-made handcrafts and the subsequent education of rural practitioners in appropriate methods and practices, the current enterprise would appear consistent. The ACE has glorified and effectively capitalized on the craft fair, American Craft magazine has become a glossy promotional vehicle and the new museum's lam-packed showcase would make America House proud. The ACC has come a long way towards fulfilling the vision of Aileen Webb in making the handmade good a valued commodity. It is no surprise then that Paul Smith continues to propagate the notion that craft moves along the changing lines of the market, that careerism, technical innovation, the spiritual involvement in making, the beautiful object, all contribute to what Aileen Webb envisioned as the efficient, productive, innovative laborer whose products are eminently salable to an insatiable American consumer.

In support of Smith's and the Council's positron, Edward Lucie-Smith contributes to the catalog a hackneyed narrative of craft history in the United States. In his essay, we are treated to the customary allegories of folk artists, the Arts and Crafts revival (the golden age) the Bauhaus and Wiener Werkstäate influences and then WWII, the seminal break that confounds the neat package of history. Lucie-Smith tries to cover as many bases as possible in his segment on current history, but, like many British commentators before him, he is uncomfortable with the pluralism and apparent freedom that art and craft enjoy in the post-war period. But before he ends, he is faithful to his appointed task in support of Smith's market history when in distinguishing art from craft he notes that the craftsman preoccupied with skill views himself as primarily a maker, a craftsman rather than an artist; that technical skills are objective knowledge passed on from one craftsman to another; that technique has evolved as the official language of crafts; and that crafts is a socialized community willing to share knowledge and experience.

The Smiths' position is untenable. Whether looking at the current period from a perspective of art history or craft history, the rise of the "new professional," a new class of skilled labor is an anachronism that has been obliterated from most critical discussion, even though remaining a stolid canon of the ACC.

The point of this argument is that we expect more from a museum than just self-serving commodity promotion. The concerns for scholarship, education and preservation cannot tolerate ideology that wears blinders to history and that seeks to influence commercial value directly. Suspicions must be raised as to the intentions of the ACC, the museum and "Poetry of the Physical" when ACE is a major source of income for the Council and a major force in the marketing of crafts. The separation of selling and scholarship is an issue that the ACC has failed to address. Only when this distinction is preserved can the museum maintain its standing of credibility within its community.

The catalog portfolio is divided into four thematic sections that correspond to the museum installation: the object as statement; the object made for use; the object as vessel; and the object for personal adornment. Paul Smith comments about the basis for these categories: "The categories do not separate works in any final definitive way. The categories were conceived primarily as a means of clarifying the complex variety of craft activity today and to aid the viewer in understanding its dynamic diversity," Clarify these categories, they do not. They are opaque and strategically ambiguous in terms of morphology, esthetic intention and stylistic analysis. Their mutual inclusivity affords the most tortuous semantics: the object as statement—l guess means art, an object that speaks with content; the object for use—obvious referral to utility, but does this necessarily exclude statement?; the vessel probably refers to the recently coined meaning by Wayne Higby that a vessel is a statement about a pot; then why doesn't it qualify it for the "statement" category?; the object for personal adornment is obviously things of beauty to beautify beautiful people. Further, the choice of objects in any category, when they are appropriate to a category, as many are not (for example, Fred Woell's commemorative spoon in "objects for use") is mediocre, at best representative of the maker's reputation and dependent upon it. It is interesting to see how these categories are weighted by number of pieces exhibited: statement (110), use (45), vessel (90) and adornment (60). The two seemingly art categories "vessel" and "statement" overwhelm the crafty categories by almost 2 to 1, and, with Paul Smith expounding the virtues of the "new professionalism," "the sophisticated mature approach to craftmanship," it seems that these convoluted categories are meant to obstruct rather than instruct.

Notwithstanding the above criticism, the strategy of the ACC is successful. They have seduced a good number of major artists to showcase their work, validating the museum's enterprise and lending their reputation to the promotion of the Council's "idea of craft." The ACC, as Aileen Webb had hoped, rightfully claims the mantle of the spokesman for craft. In keeping with the custom of the Council, I respectfully acknowledge the patronage and support of their fellows who have contributed to this success: Kington, Bonner, Mueller, Griffin, Paley, Litsios, Woell, Simpson, Prip, Pearson, Baldwin, Theide, Flynn, Long, Shirk, Tisdale, Quigley, Hamlet, Underhill, Fisch, Hu, Eikerman, Miller, Saunders, Pijanowski, Friedlich, Ebendorf, Moty, Threadgill, Aguado, Holder, Thiewes, Lechtzin, Loloma, Loeber, Jerry, Ross, Opocensky, Leupp, Raber, Reed, Schick, MacNeil, Harper, Rapoport, Banyas, Scherr, Church, Metcalf, Laskin, Bennett, Colette, Rezac, Chase, Choo, Herbst, Klein, Schwarcz.

Note: Since this piece was written, notice has been extended by the ACC that Paul Smith will be retiring as director of the ACM as of September 1987. A nationwide search is now in progress to fill the position.

1986 International Jewelry Art Exhibition

Yurakucho Seibu Art Forum, Tokyo

August 30-September 16, 1986

by Janet Koplos

This is the sixth triennial exhibition of the Japan Jewelry Designers Association, and the second international. The panel of judges included an "overseas" representative—the peripatetic Paul Smith of the American Craft Museum, Jewelry by 81 foreign artists (only eight Americans) nd 46 Japanese was juried in. But then the international balance was seriously undermined by the invitation of an additional 131 Japanese jewelers. The invitees were not specified in the exhibition, although they are set apart in the bilingual catalog.

It's difficult to generalize about a show this large, but the Japanese representation seems to indicate that gold, platinum and precious stones are still held in high esteem (not really surprising when the average Japanese woman on the street wears 50s-style costume jewelry with lots of fake stones). Tokyo is a fashion city yet still rather formal and socially hierarchical. This may explain the emphasis on ostentatious luxury in many of the precious pieces, with the extreme being a gold, ruby and diamond parure so ornate it seems mannerist. A concomitant generalization one might draw from the show is that the now well-established Western trends toward nonfunctional jewelry and nonprecious materials are still quite limited in Japan.

The one possible exception is the use of Japanese paper in a half-dozen or so pieces. But then, although paper may not be precious in Japan it is certainly revered as an artistic material. And perhaps that's why it's believable that the jury would select as the grand prize winner a necklace by Verna Sieber-Fuchs of Switzerland made of torn glossy paper and wire. Considering its material, the piece is surprisingly formal and is reminiscent of a Peruvian or Mono Indian feather cape.

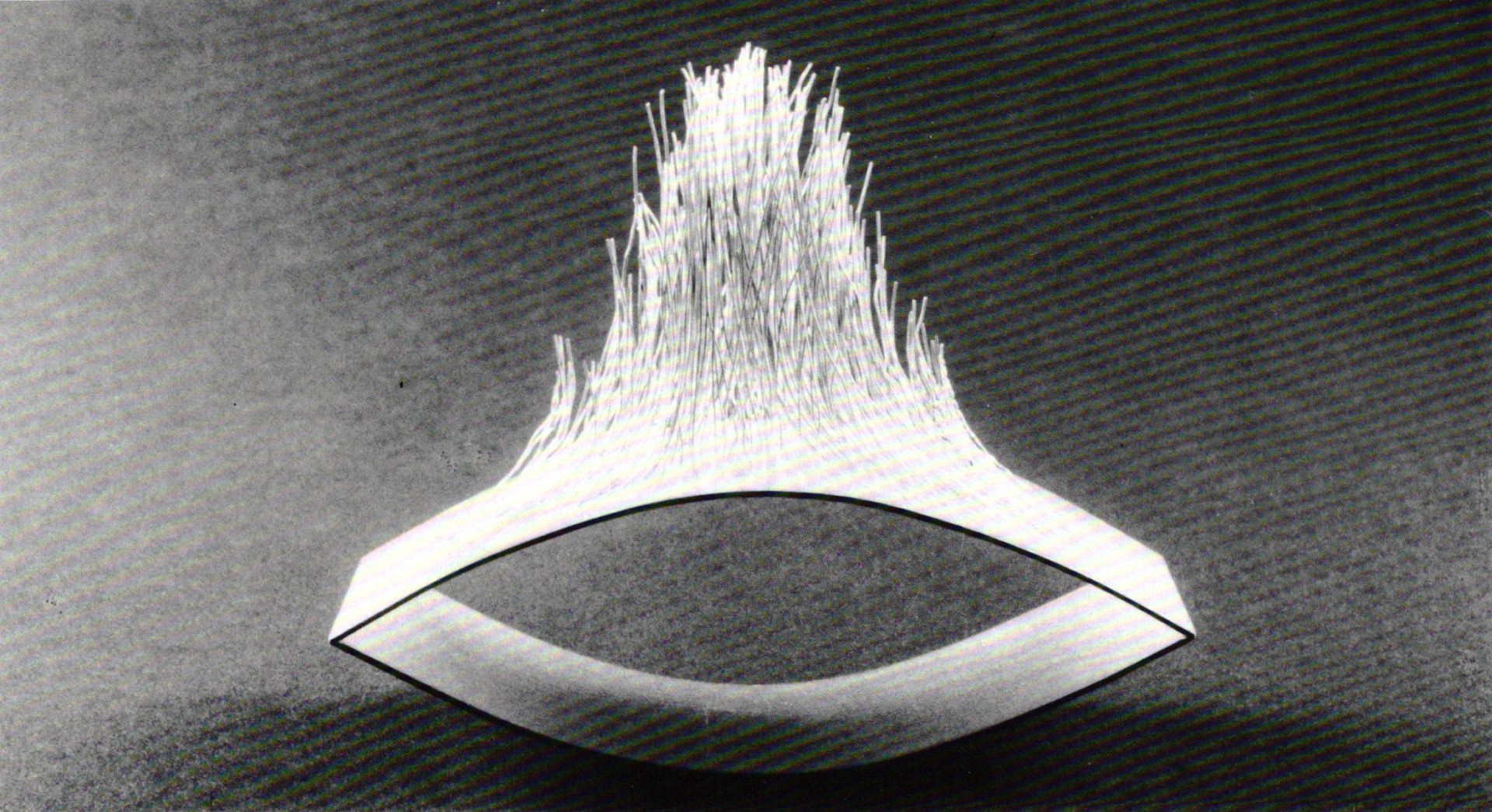

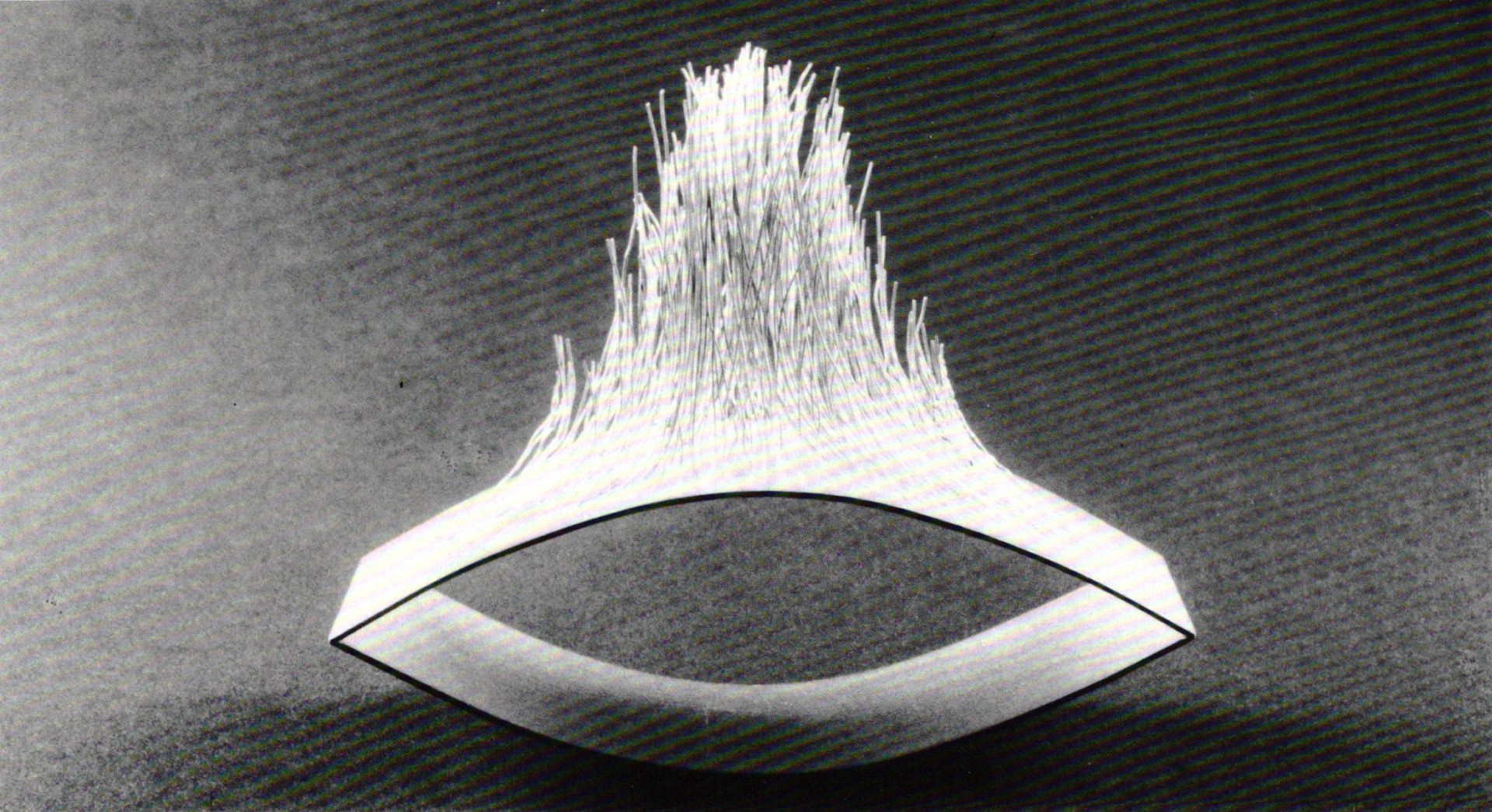

Other prize winners were Francesco Pavan (Italy) for a pair of brooches made of gold which looked like layers of corrugated cardboard; Tone Vigeland (Norway) for bracelets of silver which looked like thread; Orna Cahaner (Israel) for a hair ornament of copper, brass, iron on silver taking the form of an open-wire grid with pieces of scrap metal attached here and there; Donna Stoner (USA) for a pinched oval sterling silver bracelet with a delicate silver-thread fungi "growing" on top; Paul Derrez (Holland) for a necklace made of large smooth ovals of cork connected by thread; Hitoshi Sawada (Japan) for a silver bracelet that looks like a cross section of a pile of silver that had been compressed in a junkyard compactor; and Nobuo Arimoto (Japan) with the only prize-winning piece that includes a cut stone: a rhodium-plated silver brooch with acrylic, metallic-flaked Japanese paper and a cubic zirconia.

In contrast to the exhibition as a whole, the international winners certainly indicate a political nod to innovative works over precious jewelry. Perhaps this is a forced loosening of the Japanese jewelers esthetic?

A 144-page catalog of the show is available for 2000 yen and postage from Japan Jewellery Designers Association, 1-5-13 Horidome-cho, Nihombashi, Chuo- ku, Tokyo 103, Japan.

Report: Guest Student in Germany

by Ann Grundler

Since visiting the Fachhochschule Fuer Gestaltung (College of Design) in Pforzheim in 1980 I have wished I could study there. In October 1986. I fulfilled that wish by entering the school as a guest student (Gasthoerer).

At this time it is not difficult to be admitted as a guest student for either Germans or foreigners. Some German language skills are helpful but there are no specific requirements. Most of the professors and the shop instructors speak some English. The 1986 fall semester started on October 16, and to be admitted as a guest student at least one month attendance is required. There is no charge for instruction, only for some materials. Most hand tools are provided by the student, but students and shop instructors were generous in letting me use some of their tools at times and the school owns a lot of equipment.

The three professors for jewelry/metalsmithing design are Klaus Ullrich, Jens Ruediger Lorenzen and Hermann Stark. They are available for instruction/consultation on Thursdays at a specific time. I studied with Professor Ullrich, concentrating on new ways to set the art glass I cut, as well as catches and findings. For jewelry rendering, the undisputed master is Professor Stark. He is at the school most of Thursday and Friday, constantly helping his students develop their designs on paper.

All the gold- and silversmithing is carried out in the studios, some of which are open one afternoon per week, like stonecutting with Mr. Stapff, to practically all day all week, like the goldsmithing studios under the guidance and technical instruction of Mr. Koenig. Enameling is taught by Mrs. Miller-Durfort, stonesetting by Mr. Ratz and silversmithing by Mr. Rombach (the studio is well equipped with hammers and stakes). The pace is not as pressing as one might expect in Germany. The motivated student will find the full acceptance and cooperation of professors, studio instructors and fellow students.

Despite the low value of the dollar at this time, it is relatively inexpensive to live in Pforzheim as a student. Most furnished rooms start at DM 150 a month. My room, within walking distance of the school and downtown, cost DM 230, including central heat and use of the bath and a hotplate. A hot lunch at the school cafeteria cost me DM 2,40—a bargain.

A stay in the goldsmithing city offers opportunities for cultural enrichment in and outside the field of jewelry and for contact with other goldsmiths. On my first Sunday in town. Reuchlirg Haus, best known for the jewelry museum, had its 25-year celebration. Dr. Fritz Falk, director of the museum, presented and personally interpreted a jewelry and fashion show. Models wore the dress and jewelry of the Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo periods, all original pieces from the museum collection. Others were dressed in the Empire style, in the 60s' style, with the jewelry of Reinhold Reiling, and in today's style to demonstrate the styles of jewelry fashionable over the centuries.

I had the opportunity to meet goldsmiths demonstrating during the celebration, particularly Johann Mueller, Willi Haefele and Norbert Mack. Mack is also a watch designer and was demonstrating how he uses watercolors in the rendering of his watch designs I took advantage of invitations to see their studios and their work. I also visited Wolfgang Zipp, whose jewelry I have admired for a long time. He now teaches design and rendering at the Goldschmiedeschule (Goldsmith School) in Pforzheim.

One afternoon I spent at the Technical Museum in Pforzheim, a showcase of jewelry and watch industry. It collects both outdated machinery, old tools and complete shops of yesterday as well as some of the most contemporary. Several craftsmen demonstrated their trade, soldering, cutting stone, polishing and engraving.

The month in Pforzheim was an enriching experience. I was able to experiment with new design approaches, such as sawcuts, fluted sections and stainless steel wire. I learned to weld 24k onto sterling, make various catches and drill glass I accomplished what I had set out to do.

If you wish to study gold- and silversmithing (Schmuck und Gerate Design in Germany), write to the Fachhochschule fuer Gestaltung Pforzheim, Holzgartenstrasse 36, D-7530 Pforzheim, West Germany. Address the letter to Herrn Mueller, Pruefungs and Praktikantenamt (Room 204). The fall semester lasts from October to February and the spring semester from March to July. After being admitted to the school, you register on the day instruction begins. You must present a resume, proof of previous study/work in the field of jewelry, one passport photo and proof of health insurance (or the means to pay). For foreign students wishing to stay over three months, a visa/permit from the German Consulat or from the office for foreigners (Auslaenderbehoerde) is required.

Ann Grundler is an independent jeweler living and working in Castro Valley, CA.

Chung/Margry/Perito

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

January 11-February 3, 1987

by Desirée Midgett

The exhibit of three Washington-area metalsmiths—Haesun Chung, Eric Margry and Pal Perito—at the Plum Gallery gave viewers an opportunity to study three different styles and approaches to modern jewelry.

As if by magic, Chung's Kite series soars with greens, blues, purples, yellows, bronze tinges, unforeseen forms and unexpected iridescences. Her skillful use of colors and techniques results in captivating pins, pendants and earrings. From her simple geometric shapes and delicate curves, subtle power radiates in harmonious proportions. This new series shows that Chung's creativity is in continuous evolution.

Margry's use of grid patterns with a spot of color has a pleasing effect that is enhanced by clean workmanship. He successfully executes a design for a three-dimensional room object (a clock) and translates it into a design for earrings and brooch. His vocabulary of flatness and simplicity is clearly articulated in geometric forms that show his admiration for the De Stijl movement.

Perito's jewelry designs derive, for the most part, from shapes and textures seen in nature and in man's manipulation of nature's bounty. Her Nacho series is reminiscent of the sandscapes that one encounters in the arid West. The forms she chooses for her pieces are full of optimism and pleasurable excitement, but stable and controlled; they are sure to capture the interest of strong personalities. Her work has character and vitality.

James Barker

Jewelry Room, Gallery Fair, Mendocino, CA

August 30-September 28, 1986

by Ann Grundler

With infinite patience, Barker fabricates necklaces, pendants, brooches, rings and earrings, both singly and in pairs. His work is inspired by primitive and ancient folk jewelry. The fine lines or scratches on the back as well as on the front of the jewelry are evidence of his understanding of the primitive. The whole field of archeology influences his designs. The circular floor plan of a pit house was the starting point for several pendants, and the street plan of Cruzca, Peru was the basis for some of his long earrings. He loves older Navajo jewelry and rarely looks at contemporary work. Yet his necklaces are fashionable; they wrap softly around the neck, they are fluid, with all their links giving flexibility to the units.

In 1983, Barker received the Grand Prize Award at Intergold's Jewelry Design Competition for a necklace with diamonds, pearls and a moonstone. The small pieces of 18k sheet and formed wire are textured on several sides and soldered to form interesting compositions. These units are joined to comprise the necklaces in a balanced asymmetry.

A pair of earrings is a good example of his application of hundreds of tiny granules and triangles, stripes and squares of gold sheet. Not only the front, but also, the back is subtly enriched with these tiny bits of gold and chasing and engraving. Barker loves the byzantine and the opulent that sparkle and glitter. His work is visible from afar but invites close inspection. The back has two or three tiny plaques: one carries his initials, one the Aztec glyph for gold and one the karat stamps.

To bring color into his miniature world, Barker uses opal, diamond, zircon, turquoise, emerald and ruby. One of his favorites, and very effective with the rich color of the 18k gold, is gem chrysocolla. To Barker the whole piece is the jewel and not just a mounting for gems. He is not afraid to use a piece of bottle glass from the Nevada desert or a rod of synthetic ruby actually made for use in a laser. In a pair of earrings he set haliotis (abalone shell) with gold granules floating on top and held in place by rivets.

To James Barker, his jewelry represents talismans and fetishes. He creates in his own small world without TV or newspaper, just listening to the radio He is a multifaceted artist. Several of his pastels were in the same show.

Contemporary American Metals

Adair Margo Gallery, El Paso, TX

October 29-November 21, 1986

by Beverly Penn

"Contemporary American Metals" was cocurated by gallery owner Adair Margo and artist Rachelle Thiewes. The result of Thiewes's sensitive curatorial imput was a meaningful variety of jewelry, holloware and sculpture that dealt with many significant concerns in the field of metalsmithing. Issues of both form and content were subjects of inquiry by the eight artists represented. While the majority of the work in the show articulated these concerns eloquently, there seemed, in some pieces, to be a disparity between scale and content. By scale, I mean the size and weight relationships between forms.

Scale as a general consideration for jewelry is necessarily associated with the issue of wearability. The particular format that an artist chooses is critical to content. Most of the jewelry pieces in this exhibition are brooches. Worn on the upper torso, brooches and broochlike objects have various historical contexts and functions, each of which suggests specific materials and dimensions. A breastplate exploits far different content, materials and scale than does a corsage, though both relate to the concept of brooch.

Artists in this exhibition most sensitive to the issue of content in form are Kate Wagle and William Harper. Wagle creates metaphorical "corsages" of sterling that are patinated with the thick white luster of fine silver. The opacity and density of these surfaces seem to mimic succulent plant forms that reinforce the floral references. The scale of her brooches is perfectly resolved, and the complex and varied iconography that associates flowers with ceremony, celebration, sexuality and vanity is eloquently stated.

Harper's emblematic brooches explore medieval fascinations with heraldic symbolism and talismanic function. A "horror vacui" sensibility weaves together the charmingly disparate cells of enamel, plastic and stones with precious metal cloisons into a cohesive whole that glows enigmatically like an intricately detailed illuminated manuscript. Their badgelike scale suggests the power of preciousness and is absolutely correct.

Relationships of form and content are also resolved in the jewelry of Susan Hamlet and Leslie Leupp. Both artists wield high-tech industrial materials into structured yet whimsical compositions. Leupp refers to the frenetic pace of contemporary American culture by combining highly incongruous materials and colors. His work seems a microcosmic comment on Post Modern architecture yet, at other times, has a provocative toylike character. It plays with our sensibility of intimacy and remoteness, dependence and independence.

Functional scale as a restriction on purely sculptural or painterly expression is a critical issue in the work of Rachelle Thiewes and Jamie Bennett. Thiewes's art is at once sophisticated and primordial, luxurious and defiant. The whole is a sensitive organization of toothy or beadlike parts that are profoundly black or white. Often she introduces accents of gold, slate or coarsely variegated forms that imitate furlike membranes stretched tautly over threateningly pointed armatures. Her bracelet functions clearly as both wearable art and as sculpture that explores primitive traditions of stringing magic charms or beads. Her large-scale brooches are defiant flirtations with the limitations of wearability and function. These pieces, however, have superseded their own parameters as wearable art. They seem, rather, to be provocative investigations of handheld function, perhaps weapons, ceremonial rattles or tools, that could activate a larger, purely sculptural scale.

Brooches are traditionally two-dimensional in emphasis and therefore logical formats for the painterly concerns of artist Jamie Bennett. Substantially framed with thick gold boundaries, the color in Bennett's work functions more as noun than as adjective. Gestural and expressive, the enameled marks bear resemblance to Abstract Expressionism, which critic Harold Rosenberg viewed as a record of activity—not as a picture but as an event. With a strong formal similarity. Bennett's gestures tempt one to wonder what activity they record or herald. Salubrious in character, his boldness seems restricted, almost enervated, by a four-inch scale. As sublime as these pieces are, it is not clear whether they are about jewelry or painting, intimacy or grandeur.

Though Susan Hamlet and Helen Shirk identify two very different sensibilities in American holloware, both explore the idea of the vessel metaphorically, as a vehicle for expression rather than as a utilitarian object. In their conceptual inquiries, scale and its accompanying implications are strategic areas of concern. Hamlet's austere and powerful vessels make strong reference to Classical aspects of Post Modern architecture. They are pristine and authoritative in intention, but the reach towards monumentality is thwarted by a timidity in scale. Shirk's holloware forms of cut, jagged planes activate rather than displace the space they occupy. An allusion to desert flora is achieved through the alliance of seductive color with aggressive forms that are of a size familiar to the arid landscape. The metaphor of the desert succulent as vessel or container (the cactus is literally a preserver of water in the arid environment) is insightful and inspired.

The sole representative of the sculptural format in the exhibition is Bruce Metcalf. While sculpture is not restricted by preconceptions, of scale due to requirements of function Metcalf's work seems bound to, not enhanced by a jewelry sensibility. He purports to offer "tentative solutions to the puzzles of life" (artist's quote) but the maquettelike scale and illustrative quality of his work distance us from the content. Though technically remarkable, the diminutive scale can reduce the integrity of his narratives to cuteness.

Smaller scale is a choice, not a requirement, of using metal as a medium. There are important psychological implications of working greater or lesser than human scale that inform both the content and form of three-dimensional expression. As artists creating in real rather than implied space, it is essential that metalsmiths acknowledge these effects.

American Figurative Jewelry: Gatherine Butler, Enid Kaplan, Stewart Wilson, Bruce Metcalf

VO Galerie, Washington, D.C.

by Komelia H. Okim

The dominant elements of this exhibit were the different approaches and variety of techniques using the human figure. As gallery owner Joke van Ommen stated in her introduction to the show, "Above all this group of artists uses the medium as a means to communicate—ranging from very personal feelings to political statements."

Twilight Zoned, No Way, Jose, The Connection, Why do you Ask?, Always Something, Hold the Line, Inner Spirits, Energy and etc . . . are Enid Kaplan's titles that show strong emotional responses about everyday mundane rituals. Her comments on different social, spiritual and psychological responses transform her jewelry. Kaplan's special interest in Brazilian, Peruvian, Assyrian and Egyptian religion and mythology are evoked by her unusual color combinations of browns, blacks, reds, purples lavenders and greens painted on the copper and brass or produced by anodizing niobium and titanium. Her figures are dangling or glancing through geometrical framework, as if conveying a certain message to the viewer. They are theatrical, stylized sketchings of male and female relationships, long phone conversations and other types of human interaction. These topics are definitely contemporary, intended to draw the viewer to the issues as well as to provide a catharsis for the artist.

"I like to use the body as a stage for an idea—such as earrings that have some kind of interaction going on through the wearer's head, or a set of pins which relate to each other and can be arranged by the wearer," states Catherine Butler. This philosophical bent is clearly seen in her pin series Catch and her earring series Sleepwalk. Her pieces are executed in a minimal fashion—resembling flat paper cut-outs.

Though not dimensional in construction, the gestural movements of the bodies, the facial expressions, the hint of colors on the metal and mobile elements together create an illusion of vitality and humor. Her figures reflect a personal conviction that humor is a vital part of her approach to the work. She wants to give the wearer the toy of laughter. Catherine Butler's pieces are not static or prearranged by the artist—they permit the wearer to arrange them according to the mood of the moment—to catch or to be caught.

Over the years Stewart Wilson has created over 7,000 fetishes of warriors and chargers, which he calls "personas," obsessions of his mind and soul. He creates his personas by wrapping a framework in cloth and decorative accents of feathers, leather, straw, fur, colored paper, wire and threads. Each figure is unique in its movement and expression. The warriors measure one to two inches and the chargers two to three inches in height. Superficially, the figures resemble voodoo dolls; but, because of their playful postures and bright costuming, they become talismans. They invite you to laugh and smile with them and to enjoy the luck they will surely bring. The banding copper wires with the ends left free at the waist become a support when the warriors are stood upright. These tiny body personas are part of a street carnival in which they are both the entertainers and the entertained. For the buyer, they become a precious object that is ornamental and mystical in nature.

As Stewart Wilson states, "The personas are wrapped representatives from another dimension, definitely here for peaceful purposes. I am honored to consider them my friends. May they be for you a personal guardian and charm. Inside this personal home (a plastic box) you will find a color xerox "portrait" which is handsigned and numbered. The magnifying square is included to enable closer inspection. . . ."

What a change Bruce Metcalf has made in his recent work. His earlier work Lady in a Basket, Catching the Bomb I and II, Bird in Flight contrast with his most recent work, a series of wood pins, Series One through Eight, of female figures. These figures are voluptuously floating, waltzing, running, walking and sailing through the air of carefully carved oak and maple, some accentuated with ebony hairdos and legs, others done in simplified copper and brass. While his earlier drawings on mylar, constructed three-dimensionally, offered female and male expressions of fright or apprehension, the recent female facial expressions and body structures are silhouettes of organically soft curves and are gilded with 22k gold leaf. Beneath the gilt bright green, red and black colors appear in a crackle effect. These colors activate the figures with emotion. His later imagery contrasts sharply with earlier work that is angular, textural and disconsonant. The figures now are less obsessed with feelings and are more freely floating in space, benign in their orientation, and at peace.

Individually and collectively, the work of the four artists in this exhibition provokes some thoughtful soul-searching in the viewer. Though outwardly decorative, they are strong personal statements of the artists' social convictions.

Contemporary Metals USA

Downey Museum of Art, Downey, CA

December 4, 1986-January 16, 1987

by Carolyn Novin

"Contemporary Metals USA" presented jewelry, holloware/vessels, sculpture and relief: it was comprehensive in its inclusion of materials and processes, eclectic in its 168 examples of the personal expression of the 145 contributors, including work by juror Arline M. Fisch and invited artists Leslie Leupp, Linda Threadgill, Michael Tom, Stephen Bondi and Christina Smith.

Some artists demonstrated interest in architectonic forms and images. Michael Jerry's pewter coffee pot was a construct of linear and cylindrical units; Cynthia Cetlin's brooch was an orthogonal facade of rectangles and tubes of sterling, aluminum, brass, tantalum and niobium with tourmaline crystal. Other artists, such as Jan Craft, preferred naturalistic sources; her Landscape #6 circular brooch counterbalanced curvilinear patterned damascus steel elements with gestural gold wires. Susan Kingsley's wall sculpture Hidden Fruition, with copper leaves shielding a fecund pod of carved and colored acrylic, was representational. Skate by Ronald Wyancko suggested, in sterling silver, the graceful sea-creature. Pamela Lins, Munya Avigail Upin and J Fred Woell—to name just three of many—composed with found objects, miniaturizations and written commentary to create objects rich in narrative connotation.

Metal was often used as strips, threads or spikes to be woven, wrapped or aggressively protected. Nora Vest's Silver Figure Series, a nine-foot tall, crocheted copper sculpture, soared like an abstracted gossamer Nike. Threshold-Passage #2 sculpture by Ellen Phillips, of steel wire with bits of impaled and indecipherable film transparencies, made poignant reference to the pain of growth. Molly Hart's Window Cells relief, woven of narrow copper strips, was a symmetrical matrix from which iridescent mylar "crystals" glowed and invited closer inspection.

Humor relieved the expressions of pain, anxiety and uncertainty. For example, Sarah Perkins' Sandwich Toothpicks 11 of fine silver with red, blue and white cloisonné enamel, took a light-hearted jab at the form-function-theme game. Also noteworthy was Marjorie Simon's picaresque Rectangular Dancing Boxes, a colorfully painted brass trio on inverted cone legs with whimsical appliqués and irregularly edged open tops.

Numerous objects referred to spiritual and primitive themes. Shari Mendelson's Quiet Blues vessel, its volume pierced by golden-edged slits, its impact heightened by interplay of dark inner and subtly blued outer copper surfaces, was redolent of ancient ceremony. In contrast, Leslie Hawk evoked tension by the contradiction of apparent formal delicacy and the weight of implied ritualistic significance in her sculpture, Elevated Vessel, of blown glass and forged steel, painted a vibrant blue, purple and pink. By juxtaposing a contemporary material with a haunting cephalic form and mysterious pattern of piercing, Randall Gunther' stitanium brooch, Dream Spiral, stimulated awareness of time and history.

In general, the work in "Contemporary Metals USA" reflected preference for detail and interrelation of small elements over monumentality to build effect. Although emphasis on meaningful content brought some pieces to the brink of overresolution, it was refreshing to see a metal show where metal, as the most frequently used material, displayed its versatility in objects that provoked thought, celebrated beauty and raised a smile.

Komelia Hongja Okim

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

October 19-November 11, 1986

by Dalene Barry

Komelia Hongja Okim recently came to know another part of the United States and her work is richer from the experience. Okim spent a year teaching at the University of Wisconsin, observing the city of Madison and the surrounding countryside. In her jewelry, shown at Plum Gallery, Okim interprets this environment in metalworking techniques adopted from her native Korea.

Poe-mock Saang-gaam is a Korean Damascene technique borrowed from the fiber tradition of cloth inlay. Thin foil or threadlike wires of pure gold, silver and copper are inlaid on textured mild steel without soldering. Okim chisels the steel surface in four directional lines, positioned as closely together as threads in woven cloth Wires or foil, as thin as 32-36 gauge, are then hammered into the textured surface. In most pieces the steel was heat-colored black before the inlay work began.

Using the steel base as a sketch pad, Okim employs Poe-mock Saang-gaam to create graphic images and gestural lines. Shades of silver, gold and copper, patterned to offset one another, create a three-dimensional composition on the flat two-dimensional form.

Winter in Madison No. 7, a square pin/pendant, was the finest example of this cloth inlay technique. Delicate whisps of silver and gold played against a backdrop of gold and copper shapes, giving the flat surface vitality and depth. Geometric shapes in sterling silver, juxtaposed around the bezeled frame, embellished the dimensional effect of the work.

Winter in Madison No. 9, another example of Poe-mock Saang-gaam in a pin, featured a fanciful beaklike shape perched atop the inlaid design of gold and silver. In the pin Fall Sunset, Okim has left the top half of the steel base its natural silver color, offering a vivid contrast to the blackened lower portion. A droplet of silver resembling a pearllike moon is set into the top section, confirming this piece as an easily readable landscape.

Keum-boo, a Korean technique of gold overlay seen previously in Okim's work, was refined in some cases to a serenely controlled method of highlighting rather than simple, decorative surface embellishment. Pure gold foil is applied to either a smooth or textured sterling silver surface. This technique is also accomplished without soldering. The artist uses a torch or hot plate to attain the right temperature and presses the foil onto the silver with a burnisher.

Zebra City, a pin/pendant, combines Keum-boo with zebra wood. The wood forms a richly colored earthy foundation for the intricate design in sterling silver, suggesting a futuristic cityscape. Slivers of gold highlight areas of the silver, focusing the viewer's eye within this architectural landscape, which could easily be imagined on a much larger, grander scale. It is the earth in miniature—seen from the ground up, celebrating flash and line and the brilliance of the city.

Okim's new collection, particularly the Poemock Saang-gaam pieces, reflects a command of metalworking technique and concept that pays tribute to her bicultural world. She celebrates the best of each heritage in a composite approach that is uniquely her own. Each new series of works shows a more subtle mastery of design.

New Jersey Arts Annual: Fiber, Metal and Wood

New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ

November 1, 1986-January 11, 1987

by Katharine S. Wood

The "Annual," which is cosponsored by the New Jersey Stale Council on the Arts and four host museums, has been divided into four categories, each presented every two years. The most recent Arts Annual, which showed at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, was entitled "Fiber, Metal and Wood." The distinguished jury consisted of Glenda Arentzen (metal), David Ellsworth (wood) and Lewis Knauss (fiber).

Under such circumstances, one would have expected a knock-out show. It was not. Several of the entries, some from well-known New Jersey artists, were of high caliber, while other caused this viewer lo wonder how they could have been juried in.

This paradox was especially true of the metals section. Why was there so much banal work alongside pieces that were truly museum quality? The technical expertise on the whole was on a high level. But where was the vision?

Not having been privy to the deliberations of the jury, I can't know whether the jurors were too narow in their selections or whether they simply did not have enough quality material to choose from. One might suspect the latter, as apparently there were only 371 entries from 148 artists. This was narrowed down to 81 entries from 54 artists (in the metals division, only 24 entries from 13 artists were shown). A number of artists might have been deterred by the single juror system. With only one person specializing in each category, those who felt their style did not fit that juror's viewpoint may not have bothered to enter. This possibility was actually noted by juror David Ellsworth when he wrote in the catalog: "l wondered. . . if l, as a vessel maker, might not have discouraged many of New Jersey's fine furniture makers from applying. Clearly, there is exceptional woodwork being produced which was just not seen."

The exhibit emphasized abstract and nonrepresentational styles. In many of the more interesting pieces, there was the appearance of understatement and simplicity together with a mastery of difficult techniques. It was good to see a certain purity of design instead of the proliferation of technical gimmicks that so often substitute for artistic content in craftwork.

Among pieces that deserve special mention was Aniello Schettino's tactile and elegant Rosary, in fused and forged silver. An interesting juxtaposition of elongated rods and small round discs created a flowing unity, punctuated at one end with a small flat cross.

Charles Kumnick displayed two of his futuristic- ritualistic constructions, elaborate inventions using a variety of contrasting forms and emphasizing a combination of metal with acrylic.

Margorie Simon's humorous entry Dog Daze was an inventive mix of several metals, feathers, paint and wood that effectively combined a sharp angularity and aggressiveness with an endearing playfulness and self-mockery.

Peg Miller's enamel entry, a plate entitled Earth, used a brilliant transparent enamel on copper, fused alongside sections of bare oxidized (firescale) metal and opaque white, an image of simple strength and beauty.

And finally, of note were Susan Kriegman's attractive mokume brooches. The shapes were elegant and the cut-out areas, echoing the patterns of the mokume, gave the pieces an unusual sculptural quality.

Metalsmiths of the Midwest

The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA

January 12-February 1, 1987

by Albert A. Anderson, Jr.

The works of 22 Midwest jewelers and metalsmiths were assembled for this exhibition at Pennsylvania State University. Chuck Evans, professor of jewelry and metalsmithing at the Iowa State University and author of Jewelry: Contemporary Design and Technique, was guest curator. The show spanned a wide range of contemporary metals production from decorative jewelry to expressive sculptural objects.

A number of artists presented purely sculptural work, which contrasted delightfully to the more decoratively and functionally oriented objects. Among these were several untitled polychrome pieces by John Ready and a number of Totems by Rachna Wallach in pewter, paint and wood. To some extent, Komelia Okim's pieces in sterling and other materials also had strong sculptural intent even though each possessed some functional containment aspect as well. The most impressive of these was Seoul Bridge in sterling, bronze and anodized titanium.

Among the participants contributing jewelry to the show, Lisa D'Agostino and Sam Farmer both provided strong and complex pieces employing married-metals techniques. Farmer had a number of examples reflecting great technical precision and control, with some exhibiting expressive content as well. D'Agostino's works, while also clearly reflecting a mastery of the materials and processes, appeared to be more spontaneous in quality as well as fun to look at.

Among the other excellent artists represented were Jon Havener, Lynn Hull, Mark Knuth, Joe Muench, Thomas Muir, Susan Noland, Jean Sampel, Olli Valanne and Ann Wright. Each of the exhibitors made a strong contribution to this wonderful exhibition and left no doubt that the quality of metalsmithing and jewelry production in the Midwest is high indeed.

Several of the exhibitors are prominent metal artists who have shaped the field of jewelry and metalsmithing. In addition to Evans, artists Fred Fenster, Eleanor Moty and Heikki Seppa offered exemplary work that provided a context within which the work of many of the younger or lesser known exhibitors could be viewed and appreciated.

Of the group, only Evans's objects, a series of anodized-aluminum wall pieces, represented a major departure from earlier work. Exquisite in color and form, these pieces exhibited a wonderful sense of spirit and fun. On the other hand, Fred Fenster's elegant functional works in pewter, that included a sugar bowl, creamer, vase and wine cup, represented the continuation of a long personal tradition of graceful, raised forms and beautiful surfaces.

Eleanor Moty's spare, angular brooches in silver and gold with rutilated quartz, like Fenster's work, reflected continued exploration of a concept developed several years ago. However, one never tires of these works as each incorporates new ideas and details.

Heikki Seppa's sculptural objects in iron, sterling, brass and other base metals appeared to transcend the technical limitations of forming in metal. These pieces, seven in all, maintained a dominating physical presence when viewed together, while I questioned whether individual works were resolved sculptural statements beyond their visual impact and technical complexity.

In addition to the artists who represent the metalsmithing "establishment." a number of other artists made a strong showing. William Fiorini's wonderful damascus Smoothbore Black Powder Pistol Barrel, Tanto and Tsuba were show stoppers along with his mokumegane and damascus jewelry. Fiorini is clearly a master metalsmith with particular strength in creating forged objects.

Among the largest works in the show were several closed forms of steel and copper by Dale Wedig. These elegant green-patinated, covered, bowl-like objects each had small openings at the top from which mokumegane forms projected. Beautifully crafted, the most successful of these was a piece entitled Triangular Void.

Included among some of my personal favorites were two three-dimensional still lifes by Lynn Whitford. One of these was comprised of two raised and patinated bottle forms in copper entitled Assymetrical Pair [sic]. Highly fluid and graceful, these bluishgreen patinated objects related beautifully to each other. The other, entitled Owed to Morandi, was a series of five patinated container forms in brass and copper arranged on a board.

Kenneth Schmidt s work demonstrated his continuing concern with refractory metals in combination with other materials. It consisted of a number of brass, copper, gold-plated and titanium containers and bow forms. These vessels, both constructed and raised, combined both symbolic and purely formal elements in a carefully composed spatial arrangement. His very sparing incorporation of anodized titanium as accents in his pieces resulted in some of the most effective uses of this material that I have seen.

Sei Mobiletti: Mendini/Sinya

Gallery 91, New York, NY

February 5-April 25, 1987

by Steven Holt

"Sei Mobiletti" was an exhibition of two stories and six pieces. Of the two stories, one revolved around the design process and the other centered on the designed artifact. Of the six pieces, all were domestic objects, and all were flawlessly executed in polished stainless steel. The show—straightforwardly entitled sei mobiletti, which is an Italian phrase meaning six little pieces of furniture-featured a cabinet, a coat rack, a lamp, a stool, a table and a vase.

These six pieces of furniture first made for a rich design process story Each piece was jointly designed by Allesandro Mendini and Sinya Okayama. What made the story more than the usual vignette of collaboration was the fact that Mendini, a reknowned Italian furniture and product designer, worked out of Milan the entire time, while Okayama, a gifted Japanese designer of objects and spaces, worked out of his studio in Osaka Mendini, the initiator of the project, drew hall of each object, and after drawing a dotted line, sent his sketch to Okayama to complete. Okayama finished the drawing and then turned it over to the Daichi Company (of Tokyo) and they worked together to fabricate 33 of each design.

As it turns out, cast stainless steel was chosen over chrome because it presented an unusual challenge, and the quantity of 33 was selected because it was felt that after that point the mold might begin to show signs of fatigue. Happily, the original letters and drawings leading up to this point are preserved in the exhibition's catalog, and this added immeasurably to personal contemplation of the show. We learn, for example, that representative specimens were sent to shows in Milan, New York. Tokyo and Osaka, and that this fill-in-the-blank, connect-the-dotted-lines design approach has roots with the Surrealists who often participated in pass-along-painting exercises.

The appropriation of the Surrealist technique was only an opening gambit by Mendini, a process-based gimmick (in the best sense of the term) that he renamed "reciprocal surprise." It's the objects, then, that must still face critical scrutiny, and here (just as with the design process) "Sei Mobiletti" offers a vivid story. It's not insignificant, for example, that critical scrutiny is figuratively rebuffed by the unlikely forms that the objects have taken, nor is it insignificant that critical scrutiny is literally rebuffed by the high polish that graces each object's surface. The fact that Mendini's and Okayama's works of gesture and imagination were executed in such a permanent material as stainless steel also conspired against a close look.

When the attempt is made to look closely, it is the room that we see, not the actual furniture. Looking at the objects, then, was like seeing the mirages of six products suddenly achieve three-dimensionality; the forms shimmered in the light, the shapes dematerialized and the object simultaneously seemed ephemeral and substantial. In the end, these objects simply weren't like anything else I've seen, not even like the experiments in furniture that have been coming from Ettore Sottsass's Memphis group and Mendini's own Alchymia studio since the late 70s. These objects are much more precious, and far more curious, Mendini has used the term "virtual" to describe this "neo-Modern" work, and in this case the label sticks, for he has taken a quintessential industrial material and transformed it into a half-dozen objects of high esthetic regard.

In the letter proposing the project, Mendini asks of Okayama, "Shall we, for once, treat our design as a game?" Without diminishing the seriousness of the quest, Okayama answers affirmatively, and goes on in his letter in the catalog to talk about how each of the objects will be linked to harmonize or repel each other. Each object, in fact, did both, just as each piece encouraged the onlooker to peer more closely, even as it denied any coherence of image; the sensation was somewhat like that of looking at a new building encased totally in reflective glass. Perhaps these pieces—elegant, untitled and brilliant—were the logical product of a designer such as Mendini who has been so cerebrally quixotic over the years.

The two pieces that stood out the most—the stool and the small cabinet—clearly showed the collision between each designer's gesture; it's almost as if Mendini's famous dotted line was doted upon by Okayama, even as he struggled to bring his own ideas to bear upon the unfinished object. One could guess where one designer stopped and the other started, but that was part of the attraction of these pieces, part of the game. If the dotted line remained, it did so fluidly, for these pieces were crafted more than produced, and sculpted as much as designed. Technically seamless, the objects of "Sei Mobiletti" presented an infinity of perfectly mirrored surfaces to the world, and their success has prompted Mendini and Okayama to issue a statement indicating their interest in designing everything from jewels to urban sculpture "all, only and completely in stainless steel," which is something, obviously, for all of us to reflect upon.

A 32-page catalog, including the finished pieces as well as initial correspondence between the designers and sketches, is available for $5.50 from gallery 91, 91 Grand Street, New York, NY 10013.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Design Material Alternatives

Production Jewelers: Marketing Production

Mary Lee Hu: The Purpose and Persistence of Wire

Japanese Designers in New York Exhibition

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.