Metalsmith ’88 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

35 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1988 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Bob Natallini and Rachelle Thiewes, Lynda LaRoche, the Philbrook Museum of Art, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Eloquent Object

Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK

September 20, 1987—January 3, 1988

by Susan Hamlet

"The Eloquent Object is a show of substance assertion and great ambition. Premiering at the Philbrook Museum of Art and curated by Marcia and Tom Manhart, this exhibit on presents more than 200 objects by 139 artists in wood paper metal, leather, fiber, clay and glass. Intended as an overview of work ranging from post World War II to the present, the show demonstrates how works of art in craft media have become eloquent voices for contemporary artistic expression.

An additional objective is to prompt inquiry into the nature of craft, the nature of art and the relationship between the two. The book/catalog published in conjunction with the exhibition provides an outstanding compendium of mages together with 11 essays. It serves as a guide, if not an essential companion, for viewing this show.

To the casual viewer, this exhibition may come across as just another crafts "blockbuster," and from this standpoint the selected work certainly provides satisfaction. Strong attempts, however, have been made to address matters of greater depth. One cannot avoid making comparisons with last year's American Craft Museum's keynote exhibition, "Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical." The difference between these two shows is that the "The Eloquent Object" is considerably more ambitious and clearly academic in nature. For the informed viewer, this is a dense and rather difficult exhibition requiring multiple viewings and the assistance of the book/catalog to elaborate upon the curators' perspective.

The exhibition is organized into six areas of consideration. 1. The Ascendency of Ideas 2. The Rejection of Function 3. Illusion 4. Ritual 5 Social and Political Statement 6. Cross Cultural Influences. Upon entering the show one is greeted by a series of video interviews with artists and critics. Their remarks and insights are a splendid introduction for what follows. Thereafter, there is an attempt to create a sense of historical perspective for the work via a chronology of events over the last 50 years. This effort to sketch a timeframe tor the exhibition is quickly lost by the presence of contemporary work.

Through the device of a darkened labyrinth of viewing spaces, one is able to concentrate upon a select number of pieces exemplifying the show's six-part statement. In most cases, the featured work sits comfortably within such assignation. The delicate, partitioned Ruth Duckworth vessel works well in combination with John Mason's robust Desert Cross to epitomize the rejection of function "Illusion" is represented through prime examples of trompe l'oeil by Wendell Castle and Marilyn Levine. To illustrate "Ritual," William Wyman's Temple 27 glows mysteriously. Robert Arneson's Holy War Head speaks forcibly with political pugnacity.

For "The Ascendency of Ideas," however, the work selected does not clearly represent the message of "ideas ruling material." Mary Lee Hu's Bracelet #37 is a piece that primarily celebrates the lushness of fine materials rather than addressing the dawning of conceptual concerns. Perhaps seminal work from the 40s to 60s would better illustrate this category. On the other hand, "Cross Cultural Influences" offer particularly strong examples of artwork from the Eskimo, Latino and Afro American experience.

Larry Fuente's Oasis achieves great heights in decorative obsession with his encrusted commode throne. Alison Saar's La Rosa Negra is a quiet sacred portrait, rich with reference. These pieces and others from artists of ethnic heritage are a refreshing complement and an important inclusion to the standard fine craft fare.

While the first segment of this show provides the conditions for gentle contemplation and the absorption of message, the second portion is truly overwhelming. Barring the idiosyncrasies of this particular installation, part two strikes with a sudden quantity and variety of work. The cohesion of the six-fold statement begins to break apart as one moves from an articulate linear presentation to a broad, densely packed viewing area.

Here, historical pieces begin to appear, much of them metalwork. One sees and enjoys the work of Sam Kramer, Margaret De Patta, Alexander Calder and Art Smith. The continuum proceeds through the 70s with John Paul Miller, Stanley Lechtzin, Richard Mawdsley and Bill Harper, to name a few. While it is a pleasure to view classic jewelry/metalwork, there is a noticeable dearth of statement by recent generations in this medium. Worthy of special mention, however, is the work of Joyce Scott. Her beaded talismanic neckpiece is vivid, playful, dreamlike. Also, the Double Cross is part of a powerful quartet of beaded objects commemorating the Guyana Jonestown Massacre. She is one who can delight and disturb.

As the show continues to unfold, it becomes evident that this is no ordinary crafts exhibition. One first suspects that something is different with the introduction of Native American pottery. Later, we see work normally ascribed to the realm of fine art through the sculpture of Martin Puryear, Jackie Winsor, James Surls, Deborah Butterfield, Judy Chicago and others.

The initial effect of seeing the combination of works commonly classified outs de of contemporary crafts is quite jarring. One struggles to maintain a sense of affiliation or definition by media and field. When those defenses start to dissolve, one is left with unanswered questions such as: How should one look at Roy Lichtenstein s ceramic cups and saucers in relation to the cups of Ron Nagle? Why is the traditional blackware of Maria Martinez adjacent to a Dale Chihuly? Does Jackie Winsor's rope Double Circle share ground with the bound and stretched silk forms of Francoise Grossen? What similarities and differences exist between art within craft and the fine arts?

In many ways, this show makes clear that it is the material itself, manner of treatment, and formal concerns that can provide strong common denominators for artistic expression. For example, the sleek circular form and refined wood surface of Martin Puryear's sculpture Simple Gilt is akin to Sam Maloof's handling of a settee. There exists for both an attitude embracing clean design and craftsmanship. Another instance of shared sensibility can be seen in Sherry Markovitz's Autumn Buck and Joyce Scott's work. Here, the rich qualities of beadwork, whether on the taxidermist's form or in neckpiece format, project an equal tenor of voice. The medium of clay has surely hastened the breakdown of barriers between the two fields. Charles Simmonds, Stephen DeStaebler and Michele Oka Doner are comfortable in either realm and have contributed to the fusing of the fields.

Another measure of comparison between crafts and fine art is that of content. Since this exhibition is intended as an overview, there exists a great range in the expressive content of work. If one were to look at extreme examples, however, certain distinctions do appear. Ken Little's sculpture Red Bird, an assemblage of shoes in the form of a leaping deer, is in essence conceptually grounded. Its concern is not with shoes, but with the power of image. Material is largely subservient to statement. On the other hand, an Otto and Gertrud Natzler bowl speaks in quintessential terms about clay, glaze and traditional form. Statement is to a great extent in service to material. Both pieces address content and concept in varying degrees, yet from the basis of different identities. They cannot be viewed as speaking from the same source, nor were they made with the same intent.

What about context? Are certain works of art destined to be separated by context? Clearly, the answer is yes. In this exhibition, Lucas Samaras's Book suffers from being taken out of the fine art context. Its cheerful, childlike appearance masks a subversive content, requiring the reference of a different kind of show. Book is an uneasy neighbor to Jack Earl's earthy, humorous and openly erotic "I Met Marsha in a Bowling Alley . . ." and surely strains this show's notion of "eloquent" object.

If the boundaries between line art and art in craft indeed are blurring, then "The Eloquent Object" exhibition is the first to make manifest this claim. In drawing together work from across the borders of art conventions under the rubric of "objects," this show poses the challenge of definition. While this show does not and cannot provide answers at this time, the curators have succeeded in fulfilling their objective—"to prompt inquiry."

This exhibit will be traveling through 1989 to Oakland, CA, Boston, MA, Chicago, IL, Orlando, FL and Richmond, VA. A review of the book/catalog that accompanies the exhibit appears elsewhere in this issue.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bob Natallini and Rachelle Thiewes

Fine Arts Gallery, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX

November 2—24, 1987

by Elizabeth Skidmore Sasser

Bob Natalini's shrinelike constructions and boxes recall the words of John Donne who found in "one little room, an everywhere." The small universes, displayed recently in the gallery of the Art Department at Texas Tech University, contained an assemblage of objects described to me by the artist as "all of the things I love," combined with kinetic action, flashing lights and electronic sounds.

Programmed to heighten the mystery and resonance of each piece, the sound and lights were triggered by the movement of observers, even shadows activated the sensors. Natalini's early auditory ventures and experiments with animation were first introduced in his jewelry designs/sculptures, which the artist regarded as "little worlds which had windows with things inside like tropical beetles from Brazil" or lights that winked constantly until the batteries inside needed to be replaced. Natalini observed, "At some point, my work jumped to a larger scale that enabled me to have more freedom to expand and to do more complex functions with electronics."

In Untitled 1987, the viewer is the activator of a motion detector that releases a musical sequence composed of "manipulated acoustical and natural sounds," including the calls of desert birds, a chorus of voices, water sounds, resonant air sounds and bells. Fusing technology and art, the visual aspect of Untitled 1987 focuses on two balls, like meteorites of planets, which project from a peach tile background; they enter space with a reminder of Magritte's famous engine roaring from a mantlepiece. The lower ball, embedded with fragments of glass, has at its center a circle of LED lights, which blink in patterns around a doll's eye (the lid painted "monster green") that slowly opens and closes as it revolves. The upper sphere is covered with aggregate and colored pebbles, Master of miniaturization, Natalini has opened a small window on the surface. Through this screened opening, a rotating carousel displays a sequence of 30 tiny objects, among these there are a mouse tooth, an infinitesimal baby sea horse, bits of scrimshaw, patches of astroturf, watch parts and a microscopic photograph of the artist with a beetle's head.

For Natalini, a beetle seems to hold a peacock's plumage in the iridescent microchip reduction. With a finely tuned antenna, he reaches out into the world of nature as well as the world of man-made debris and discards. From these sources Natalini fastidiously selects fragments and textures wood covered with cracked and crazed paint or the elegance of rust and layered metals corroding into chasms and craters.

It is from such neglected memorabilia that Untitled 1980 is assembled. The exterior is covered with pear buttons, on either side there are three crucifixes in glass tubes that glow when the electrical current is turned on. The artist hastens to make clear that his work should not be characterized as a religious expression. It is a blend of the sacred and profane, both to Natalini are equally wonderful. He is also influenced by the symbols and mandalas of Tantric art I love things that have a kind of mysticism he says, "I can't necessarily say why, I try to make things that are unusual, things that will thrill me."

Enclosed in the button shrine, there are pieces of Chinese paper, threads, weathered wood, the metallic glint of a silver chain and a bicycle reflector. These unlock the viewer's sense of the uncanny and the surreal, releasing the imagination to find its own figurative associations. A sudden jolt may occur with the discovery of a child's plastic ray gun behind the fabrications. The back of the box is no less remarkable than the aspects of inside/outside.

Here, the circuitry and color coding form intricate abstract patterns. The various functions and methods for mastering the controls are indicated by directions lettered on attached cut-out profiles of human heads, a message that the mind is in control. The sound produced s an ethereal melody interrupted by strange noises; it may be on for four minutes and then off for a period that varies from four to 50 minutes.

Natalini brings together disparate sounds and objects using an intuition that seems to have its origins in the roots of the human race; at the same time, he reaches out to encompass the newest frontiers of science and technology. He involves people in his art; it is their actions that animate the sound and right systems. Developed to increase the sensory excitement and enliven the humble materials these systems form multilayered symbolic puzzles. In the artist's words, the aim is "to create things that are unusual in a world of boring things."

Organized by Leslie Leupp, Professor of Art at Texas Tech University the exhibition of Bob Natalini's sculptures was synchronized with a small exhibit of Rachelle Thiewe's metalwork, as well as pieces from her personal collection. The jewelry, made by well-known artists and craftspersons such as Helen Shirk, Bruce Metcalf, Ester Knobel, Leslie Leupp and others from Europe and the United States, conveyed a catholic taste, a sense of humor, an admiration for the extraordinary, as well as respect for traditional materials and methods and an equal interest in unconventional media and concepts of jewelry as body sculpture.

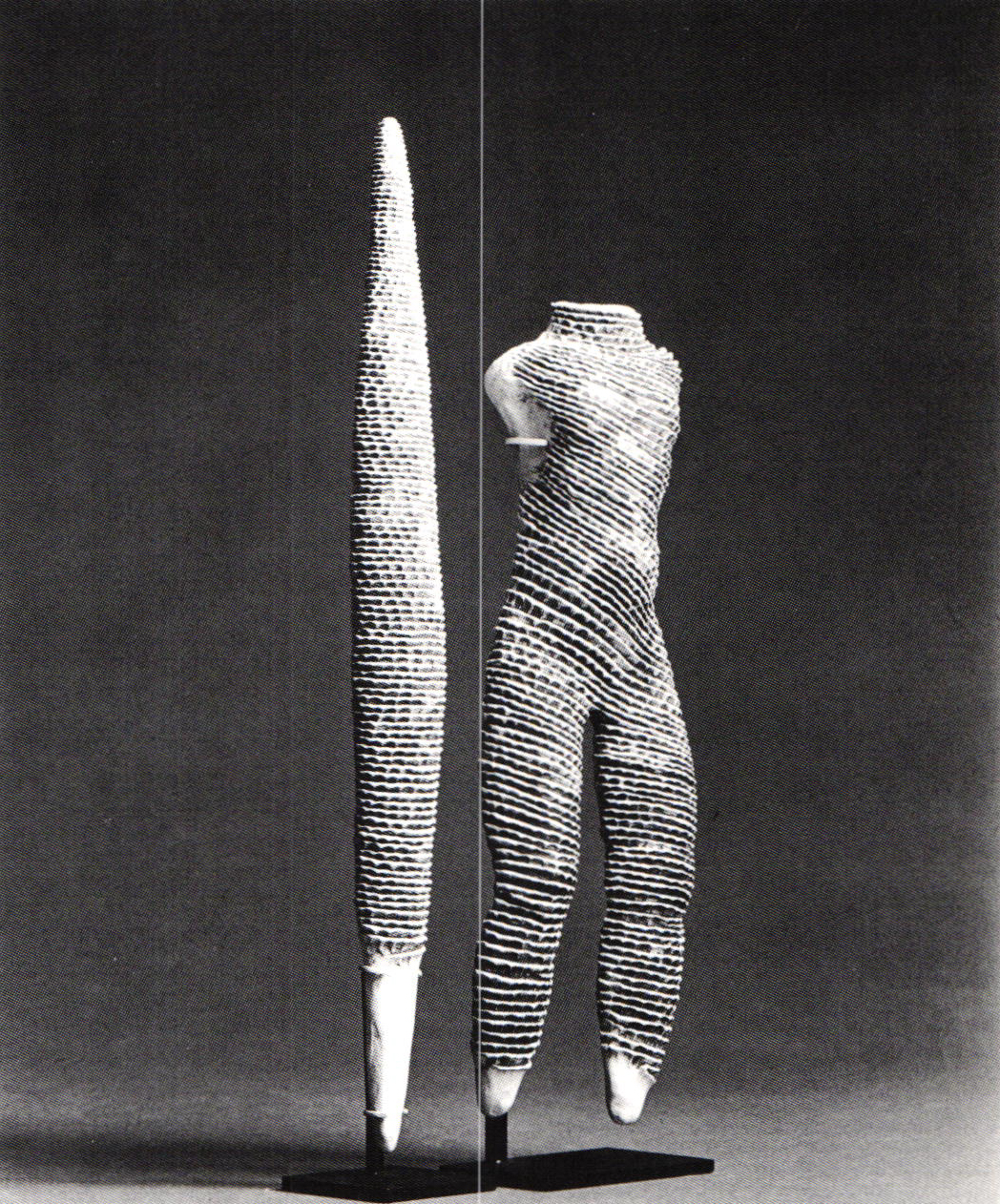

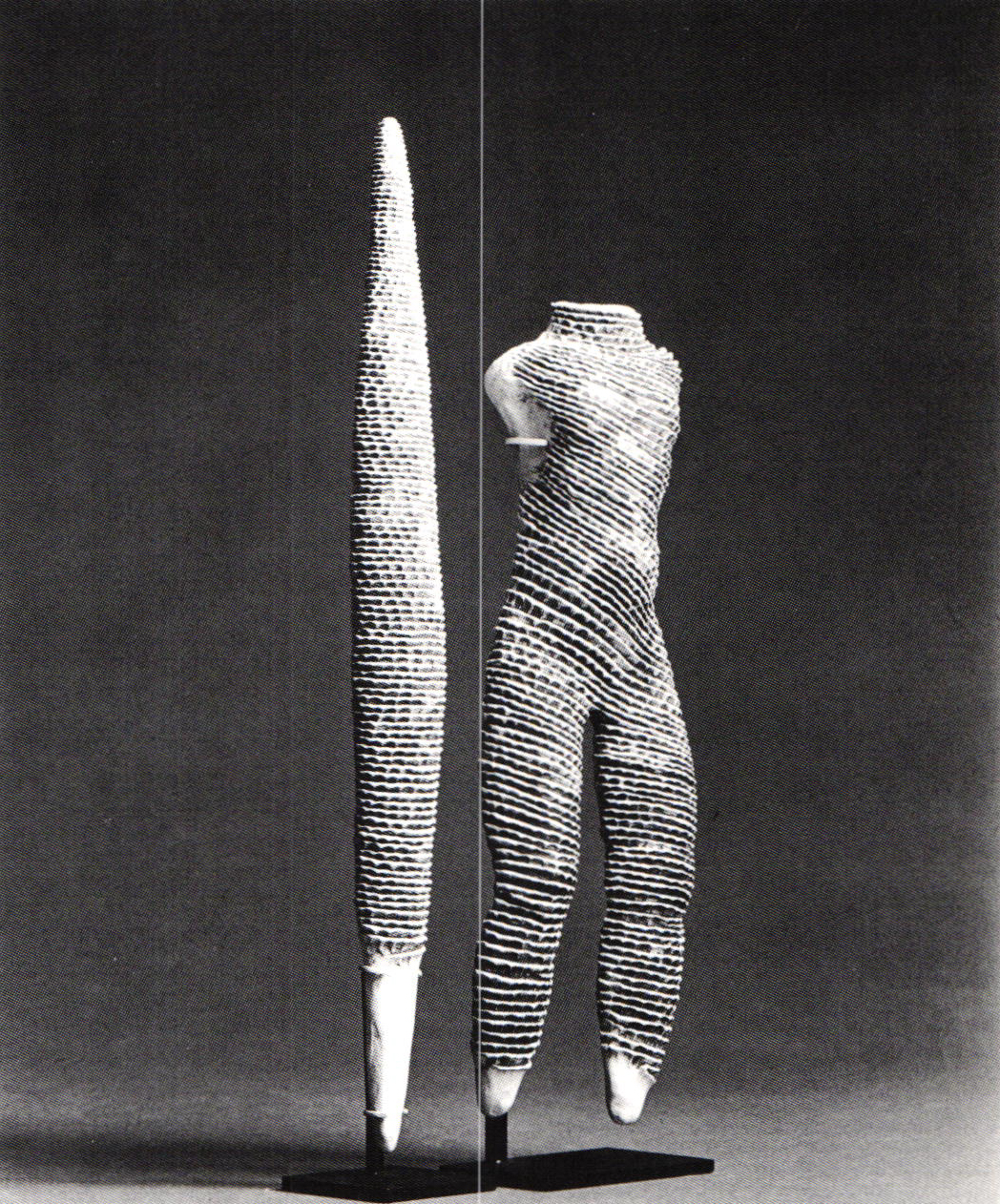

Links between the work by Thiewes and Natalini were present in the auditory and kinetic experiments that each explores. The pins and bracelets by Thiewes are set in motion by the movements of the wearer, parts slide together or tap each other producing tonal nuances from gatherings of silver quills touched by slate disks. Movement is implied in a piece like the Wire Pin. Even at rest, it appears poised for action like a finely balanced javelin. In Thiewes's metalwork there seems an inherent threat of danger. Her needle points and slender ovoid shields suggest the wizardry necessary to transform a Zulu's spear into a scalpel.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lynda LaRoche: Fragments and Facades

Artifacts, Indianapolis, IN

November 13-30, 1987

by Steve Mannheimer

To say that Lynda LaRoche's jewelry is about architecture is simply to locate her point of departure. Her destination remains open and her methods, the conceptual itinerary as it were, remains, elusive, even problematic. When the largest art form is translated into the smallest, the transformation is flavored by a hint of transubstantiation. LaRoche wisely refrains from merely miniaturizing buildings into these 10 brooches. Rather, she purifies, elaborates, disassembles and reassembles, ultimately disguising her monuments.

They may be abstract, as in Fragment with Black Diagonal, a geometric tumble with a triangular "roof" element at the bottom. Or they may be pictorial as in Caribbean Fragment in a Landscape, a horizontal, black and slate rectangle set with a smaller, gold and silver rectangle capped by a sawtooth "roof."

The other eight "fragments" and "facades in the exhibition tall between these extremes retaining a semblance of representation LaRoche provides a vertical reference by locating the pins across the tops of the pieces. She reinforces the orientation by showing us the "ground plane beneath her edifices, tiny slabs of slate or green and pink marble. Upon this rock she builds her art.

According to LaRoche's written gallery statement, she has taken her cues from post modernist architecture and "New Wave" Italian design. LaRoche should find ample inspiration in such visual lushness and invention. Yet, the forms she manufactures are so minimal and geometric, attuned more to the purist spirit of Modernism.

This paradox is greater than a mere semantic tussle. LaRoche's immaculate workmanship may be the jeweler's art, but as building craft it is possible only in an architect's dream—the "zero-detail" look of materials joined perfectly. (And what materials! Not steel, nor even stainless steel, but silver.) In effect, these are ethereal, otherworldly visions reminiscent of Miles van der Rohe's conceptual collages—a window floating here, a floor there. Cartesian romances untroubled by structural necessities.

Or, we may consider these brooches as buildings glimpsed through the wrong end of a telescope: grime and soot squeezed out, chipped cornices smoothed while they shrunk, all made precious in compression. The rich materials of jewelry become that preciousness (in both senses of "become" to transform into and to appropriately adorn).

As lofty as they may sound, the works have a tendency to remind us of handheld artifacts. Facade with Golden Triangle could sneak by us as a Deco revival cigarette lighter, albeit an elegant one. Elsewhere, as in Square Facade with Molding, the sense of scale hovers above three landings: the immediate sense of the physical object, the illusion of a single window and ledge and the illusion of a huge, ceremonial arch.

We are left hanging, clutching to a brittle edge of an esthetic, a distillate of ornament. Perhaps the perch is too small 10 support jewelry's traditional mood of celebration or theater. Yet, at its best, it offers a thin, chiselled pleasure, like a face so perfect in its plainness that it silences the talk of beauty.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carrie Adell: On the Rocks

Elaine Potter Gallery, San Francisco, CA

November 17—December 31, 1987

by Roberta Floden

Fascinated by organic shapes and natural forces, Carrie Adell has built her reputation on engaging, often flashy and frequently award-winning jewelry inspired by braided garlic bulbs, beehive hexagons, tetrahedrons, ball and sockets, kitchen sink grids and solar winds. By comparison, the pieces she has on exhibit at the Elaine Potter Gallery are subdued and traditional Called "touchstones, they are indeed a continuation of Adell's tribute to the earth's geology. In genre, however, they are reminiscent of ornamentation it its most elementary if not original form—the perforated stone bead.

But one should not be put off by her humility and reverence. From this minimalist archetypal shape, Adell has developed interpretations as varied as those brought forth from the geological processes themselves. Constructed from sheets of metal (shakudo, silver, copper or gold) that have been overlaid and collaged with contrasting metal patterns and patinas, her touchstones offer provocative textures, articulations, grains in low and high relief and precious and semiprecious stones.

Adell's skill at painterly abstraction (her original training was in the fine arts), her obedience to process and her superb craftsmanship are in evidence on both the fronts and backs of her pieces. Details are perfectly analyzed, and intrinsic qualities of the metals are exploited. Surfaces—contour, texture, tension, reflection—provide a rich play of light and dark. Sculptural yet functional, each touchstone is a fresh approach to a basic form.

As testimony to their name, touchstones are for touching. To tempt the wearer to interact with their tactile qualities, Adell has provided several supports upon which one can arrange and rearrange the touchstone by size, color or texture. Most of them can be worn, front or back, on fibulae or "multipins" (gold safety pinlike mountings) that can be used as earrings, as a brooch or suspended from a chain or collar. Sticks and Stones is an eyecatching variation of this theme, with a cluster of sterling sliver sticks tied vertically by shakudo wire to the patterned gold matrix of the touchstone. Another variation is the arrangement of from one to five tubed touchstones on a gold neckring.

Some of Adell's necklace designs cannot be altered. Looking every bit like pebbles and stones on the bottom of river beds, Goldrocks and Pebbles is made with five touchstones hanging in a subtle configuration from five strands of dyed-to-match seed pearls. Inclusions #1 and Inclusions #2, her tours de force, employ large touchstones with gem studded intrusions on collars of (10 to 12) seed pearl strands. All of these neckpieces have cleverly concealed closing devices, integrated into the distinctive touchstone design.

Although reductive, even simple in conception, Adell's touchstones have none of the staleness of convention. Indeed, the interactive quality of the pieces and their purity of form introduces a clarity, a conceptual rigor and an esthetic that harkens back to the development of human culture and the belief that the act of transforming an object imbues it with the magical properties of a charm or amulet. It is this talismanic quality that empowers Adell's touchstones. She has created not only a loving marriage of art and craft but a classic jewelry of great psychological integrity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Kazuma Oshita: The Art of Metal Hammering

Alexander F. Milliken Inc., New York City

May 2-June 3, 1987

by Christina De Paul

As artists increasingly reject the definitions that have historically separated metalsmithing and sculpture, the two activities seem to be converging. A recent illustration of this amalgam was the solo exhibit of the works of Kazuma Oshita.

Kazuma's work shows breathtaking technical expertise. At first glance the casual observer, seeking out metal objects, may pass over the lush texture of a worn leather jacket, the intricate folds of a sheet of crinkled tissue paper, the rich marbling of a polished stone tabletop. It is only upon closer inspection that one realizes those deceptively detailed items have also been created, as Alexander Milliken puts it, from a "flat, cold, hard piece of metal," transformed into art by the hammer of a master.

The work of the Hiroshima-born Kazuma, who first came to the United States some 10 years ago, hovers somewhere between realism and surrealism. In The Love or . . . or About Love, for example, a tall four-legged stool serves as the pedestal for a single rose stem lying across its seat—all very ordinary except that the rose bud itself is in violent flames. In the brass and bronze Nostalgia Table, a quill, a single white glove and a set of scales resting on an ornate side table provide the nostalgia, while a single wine goblet stands irrevocably broken, its shards strewn beside it. In Barbed Wire Dream, one of Kauma's smaller pieces, an egg and a butterfly are suspended mysteriously between threatening, imprisoning wire strands.

It is not lust content and texture that surprise in Kazuma's sculptures, however, there is color. Not only is he in command of the hammer, he is also a wizard of patina techniques. The leather jacket draped so casually across the table in Amaryllis and Cat begs to be touched, a result not only of the folds and individual stitches hammered with such deftness into the brass, but also of the coat's lustrous burnished brown. In Letter to Send Her, a personal narrative depicting two addressed envelopes, one crumpled and the other aflame beside it, the brass paper is of an incredible white. The central object in Life—Rose is blood red, from petals to leaves to broken stem.

All of these elements—Kazuma's skillfulness with patinas, his hammering mastery, his realist/surrealist bent—come together in the striking brass and bronze Duet. Both clarinet and violin are detailed down to the last key, the individual strings. The seats of the pair of high-backed Edwardian chairs give the impression of deep green velvet. But the "figure" holding the clarinet seizes the eye and holds it: a stunning black cape covers a disembodied entity in one chair; a detached right hand holds the clarinet; neither head nor trunk nor extremities explain this spectral figure. The violin lies mute upon the other chair, awaiting its part in the duet.

Kazuma's more whimsical side comes out in other pieces. In Wind of November an autumn gale from an unseen window blows across the table, bending candle flame, causing pictures tacked on the wall to flap wildly and disarranging the tablecloth. Perfectly formed pears tumble, while a crumpled baseball cap is undisturbed. Téte-e-Téte features a serving table that bears two teapots with spout "noses" lacing each other confidentially, nearly touching The Cat on the Table reclines regally, hind feet and tail draped over table's edge. The results of the cat's handiwork surround it: a serving bowl tipped, with apples and pears strewn across table and onto the floor, a wine glass shattered, a sprig of flowers in a vase surviving untouched. The eyes of the cat are so lifelike, they seem to be searching for new mischief.

The smaller works in the exhibit, all of them wall pieces in the manner of Joseph Cornell, extend this whimsy in their more surrealistic motifs. Life Time is a two-part composition in which a single taper burns from high to low. Swimming Doll portrays a mannekin prone on a plank that is balanced on an egg fulcrum. The doll seems to be swimming toward an open birdcage, just out of reach, while two dragonflies cling to a wall.

Alexander Milliken has noted that vision alone has little meaning without the ability to implement it. The sheer craftsmanship of Kazuma satisfies this requirement and successfully combines the arts of metalsmithing and sculpture in works that appeal and challenge.

A 16-page illustrated catalog of the work in this exhibit is available from Alexander F. Milliken Inc., 98 Prince St., New York, NY 10012.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Barbara Mall: Jewelry

Swan Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

September 11—October 3, 1987

by Myra Mimlitsch Gray

There is no question that Barbara Mail is a veritable master of craft and design. Each piece in this exhibition was meticulous in execution and at the same time fluid and poetic, a graceful experience for the wearer.

Color is an obvious concern to Mail. The use of various gold alloys contributes to the richness of color and is essential for certain technical considerations. In Eclipse, 24k gold is necessary for a bezel that is pushed over a very fragile snail shell in the pin, while the shear beauty of its color brings forth a coral glow from within the shell.

Mail's surfaces are the results of playful inquiry into wax. Sheets of wax have been pressed against various surfaces to acquire rich textures. These samples are then cast and later manipulated; some formed into sensuous tapering tubes, or spicula. Mail does not select these surfaces arbitrarily; in this group of work she has used wax impressions taken from ribbons that belonged to her grandmother.

Mail's jewelry abounds with personal iconography that has little relevance to the viewer. The pin From Refugee to Rogue is perhaps the most personal and also the most extraordinary piece in the show. It is an homage to the artist's grandfather. The linear motif of its design refers to his cigarette, with a diamond and rutilated quartz poised on the tip, reminiscent of the heat and evanescent smoke that is an ageless memory. An elegant arc of forged wire loosely traces his journey across Europe. A fragmented impression of her grandmother's ribbon is draped across these forms.

When one learns the stories that are the inspiration of Mail's work, each piece becomes more endearing. The grandfather pin becomes an icon, a medal, a charm, a locket, a journal, In fact, Mail's memories in words, thoughts, transcriptions are sketched in form by the materials' handling.

Many of the pins seem to be fabricated with a clear formal strategy. They are like the same score of music that has been notated each time with a slightly different hand. The most compelling and provocative works are those that show freedom from the rigors of design. From Refugee to Rogue seems to take the most risks. Here, Mail has invested equally in the exploration of form and design, as well as in her thoughts and memories.

In a statement about this work Mail wrote that her art is "an attempt to isolate a fleeting moment, examine it and turn it into a Jewel to be contemplated, experienced, worn," Mail's work succeeds on many levels; it is foremost an elegant and unique contribution to the realm of fine jewelry, it is also a masterful survey of design and technique and it is a lender recollection of personal experience.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Daniel Clasby Daniel Jocz

Elaine Potter Gallery, San Francisco, CA

May 26—June 27 (Clasby),

October 13—November 14, 1987 (Jocz)

by Joyce Clements

Contemporary metalsmithing could hardly be more trenchantly manifest—certainly not more ironically represented—than in the diminutive and largely metaphorical sculptures by Daniel Clasby and Daniel Jocz.

Clasby's show is his first in the United States, Originally from Montana, he now lives and works in New Zealand, where he has established and operates his own studio and "Associated Workshop." The latter is an atelier with 11 jewelry workstations. Clasby rents these spaces and does some teaching as well. His own work now is entirely sculptural-miniature (doll-house size) constructions in silver, various carats of gold, marble, gemstones, ivory and wood. Clasby's technique is eclectic—fabrication, interlacing, wood carving, casting—and while his technique is faultless, it stands entirely in the service of the idea.

As reviewer Warwick Brown of Art New Zealand observes, the sculptures are well within the mainstream of Surrealism. The observer is treated to a suspension of reality, an alleviation of the ordinary and offered the challenge and feast of the artist's transmogrification. She looked me over and I guess she thought I was alright, alright in a limited sort of way, the title borrowed from a blues tune, finds itself expressed by a carved ebony arm and hand (scapula clad in fluid 22k furied cloth), clutching a silver crutch, the whole of which languidly rests atop a folding silver and gold table. Clasby is so clearly entranced by the verbal made visual that the sculptures and their titles are inseparable. It is easy to imagine the relish with which Clasby latches onto a verbal fragment or turn-of-phrase and enjoins it to his conceptual literations—emanations both personal and universal.

In God Only Knows What We Expected, Clasby presents a ceremonial apparatus—a chariot or trailer (after all, it has a hitch!) from the top of which, flanked by two candles of silver, rises a crucifix on a long standard. Midway up the standard protrudes a rod and towel circle, through which a vestment of loin cloth of 22k gold is draped, A gladiator's shield or disc of picture jasper is mounted to the front of the ebony wheeled vehicle.

Other works, Still Life, (an ebony casket on a silver gurney), and Learning to Live Without Art, (carved boxwood hands and arms garroted in a padlocked stock, holding a silver tray on which are three skeleton keys) are disconcertingly, perhaps luridly fascinating. Others, for example, Rock Therapy, (a rocking horse-like contraption) and Not for Sale (the frame of a sail boat fully outfitted with working rudder, tiller, lines and oars) can be appreciated for their sheer whimsy. Irony in art is sometimes underwhelming; paradox can be presented in such an obvious way that once assimilated the "thrill" is gone. Not so with this art. Daniel Clasby's work is acute. His sculptures are invitingly and consistently confounding, a little devious and pointedly witty.

Daniel Jocz's work derives from Constructivist sculpture. Because of his apparent commitment to the vocabulary of hard-edged geometric shapes, Jocz's work has a feeling of clarity, strength and integrity. This type of structural presentation makes an explicit self statement, an intellectual rather than an emotional one. And yet, the combination of forms inevitably introduces a sense of enigma, suggesting a commentary of meaning other than that which is directly conveyed by the shapes. The kineticism Jocz introduces into his constructed forms adds a dimension of playfulness which is delightful. Wearability, in this instance, adds to intrigue. Taper, a geometric crescendo to be worn around the wrist, is a sterling silver and 18k, hinged, married metal piece, consisting of 18 rhomboid cubes that can be arranged into myriad combinations of folded forms.

No more than a block away from the Elaine Potter Gallery at an entrance to the Davies Symphony Hall stands a welded plate steel sculpture by Fletcher Benton, Balanced, Unbalanced T. The comparison between this massive geometric piece and Jocz's newest work, the Jazz Geometrics bracelets, is unimpeachable. It is as if the T succumbed to gravity, rearranging itself with flexible links, fluid despite its monumental scale, anchored despite its spatial freedom.

Jocz is an absolute master of mechanisms. Leger demain is a part of his work, allowing linkages to be fluid but not infinitely manipulable, constrained but free. Both in the necklace and bracelet Slicks, tubular forms of married sterling silver and various carats of gold are confederated into a thicket, whose movement, linkage and fastening are wondrous. The slicks lay orderly and elegantly in alignment when worn or placed in circular configuration, but the thicket can be made seemingly haphazard and impenetrable by a bit of jostling. The planning and craftsmanship demonstrated in these pieces tends to reinforce the artistic accomplishment of the work, for in no way do the mechanics interrupt the impact of the concept's realization, and, in fact, conceptually and spatially enhance it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Richard Mawdsley: Master Metalsmith

National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN

August 16—October 25, 1987

by Linda Lindeen Raiteri

As Richard Mawdsley cleans the pieces for this one-person show, he examines each one, silently noting the level of craftsmanship, the degree of success in expressing his vision. Some of the work, made as gifts for friends or family, has never been exhibited. Some he has not seen in 10 years. He wants to place these pieces that represent artistic breakthroughs side by side to see where he has been, where he is going and what he would like to take with him.

"Intricate, delicate, protracted, heavily involved" are the words Richard Mawdsley uses to describe his work. For 25 years he has worked with one type of material: tubing, and he seldom creates more than one or two major pieces a year.

The centerpiece of the exhibit, a 17″ high sterling silver drinking vessel Untitled Standing Cup is drawn from vessel forms prominent during the Renaissance and Mannerist periods. He places it so that it is both the first work seen and the last. The geometric borders reflect the formal design of his early career. The expressiveness of the face and the realism of the woman's hair demonstrate his recent challenges.

This masterpiece, finished in 1986, is both a culmination and a fulfillment. In contrast to much of the exhibit, Untitled Standing Cup conveys a restful quiet, a serenity. Each strand of hair on the woman's head shimmers with life.

Mawdsley pulls his images from legend. His most forceful pieces depict that moment between the generation of elemental power and its unleashing.

The sterling and lapis lazuli Medusa pendant (1979-81) bares a barbed and heartless rib cage, a miniature torture chamber. Her undulating strands of hair are delicate, controlled.

This suspended animation is repeated in the unfurling of the 1986-87 pearl and sterling pin Corsage, where the lines approximate the weight and speed of mercury. In Headdress #6 (1984-85), a pendant of 18k gold tubing, moonstone, tantalum and titanium, the snakelike hair surrounding the repouss face is rounded and elonégated more like tentacles.

Yet it is not the hair that contains the Samsonlike power of these images. In these pieces Mawdsley conveys the strength of beings who are fully, menacingly present, ready to explode out of the stillness that holds them temporarily in abeyance. She-Ra, Princess of Power appears incarnate when a mere mortal dares to wear the 1977 Venus Fly-Trap pendant of sterling and black onyx. The nude torso of this fabricated and cast jewelry piece entices one into the thorny dangers of her barbs, while the well-known belt buckle Gonerii, Regan, Cordelia (1976), made as a response to "the dilemma of the woman's movement and having nothing to do with Shakespeare," using the same female figure as Venus Fly-Trap, but in triplicate, implies protective magic for the wearer.

As Mawdsley matures in his work, the potent stillness of the early mechanical forms spills and softens, as in the face of the woman of the centerpiece of the exhibit, the Untitled Standing Cup.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Report: Graft as Content

University of Akron, Akron, OH

October 31, 1987

by Donna Webb

This one-day symposium, organized and curated by metalsmith Christina De Paul, was the first of its kind to address the issue of craft and its meaning. An exhibition of works by Carol Kumata, Karl Bungerz, Gene and Hiroko Pijanowski, Lisa Norton, Whitney Boin, Donald Friedlich, Rebekah Laskin, Laura Marth, Kazuma Oshita, Helen Shirk and Rachelle Theiwes was held during October and November in the university gallery.

During the symposium's morning session five speakers presented a statement in definition of craft as content. Bruce Metcalf spoke for the possibility that careful craftsmanship can be part of the meaning of a work, as that found in the brushmarks of David Park or the splashes and drips of Jackson Pollack.

Hiroko Pijanowski spoke about the meaning of craft in Japanese art where specialization allows craftsmen to hone their skills. She also described the acquiring of skills as a discipline akin to meditation; strict discipline leads to selflessness, the goal of Zen meditation.

Karl Bungerz described his work as a model-maker for industry and how those standards and processes inform his work.

Carol Kumata told us that her work is at a juncture, moving away from reproducing her ideas through craft, to a way of working in which the act of building the piece and the revelation of the idea are coincidental. In these latter pieces she believes craft is much less of an issue.

Michael Dunas described the possibility of working solely to express craft. He isolated for us through allegory the pure ore of craft with no contamination from individual expression.

The afternoon session moderated by Sarah Bodine was open to questions and comments from the floor. The ensuing discussion owed its character partly to Christina DePaul's request that the symposium focus not on the issue of "art versus craft," but rather on "craft as content." This decision was important, for it forced us to examine not the enemy without (the world of fine art) but the enemy within—our inability as people involved in craft to clearly define the basic terms of our discipline.

No one definition of craft could be agreed upon by participants in the symposium. As Michael Dunas said, "I understand that we need to take a stand on craft but I don't know what it is I'm standing for." Janson's History of Art, probably the most commonly used introductory art history text for the last 20 years states: "Originality then, is what separates (the making of ) art from craft." It is clear that most people engaged in craft reject this point of view. Several opinions were discussed at the symposium concerning the definition of craft. Some characterized craft as slow, careful making. The value and therefore the meaning of careful craft was hotly contested by the contingent from Cranbrook who raised the possibility that careful craftsmanship is a reactionary activity. A third point of view was that craft exists as a continuum where the more careful is on one end and the more spontaneous on the other.

Limiting craft to careful making falls into the trap set by Janson, which clearly separates art and the crafted object by focusing on care rather than on making of esthetic choices. If craft is a reactionary activity now, then standards of craft must change with time and express the values of the period.

A definition of content was more generally agreed upon as a broad range of meaning present in works. The only serious objection came from Mitchell Kahan, director of the Akron Art Museum. He contended that content should be described as existing in sculpture and painting where metaphorical and symbolic issues are explored, while something as yet unnamed was present in craft objects as a result of the process of making. Sarah Bodine pressed Kahan to call this unnamed quality content but he did not feel comfortable with that definition instead describing what he called a psychological meaning present in crafted objects.

We read craftsmanship in the same way we read other visual evidence. Knowledge of why an artist uses a technique, gesture, formal or symbolic element is valid information, useful in assessing intent and meaning in the work. I believe that visual information is the "speech" of making and as such has content.

What should come out of discussions such as these is a clearer idea about the meaning of craft (a manifesto is almost too much to ask for) which will allow a compelling case to be presented to the critics and art historians who seem to have such a formidable hold on our destinies.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

2009 Radiance Enamel Exhibition

Carrie Adell: Energies of Transformation

Superfit’s Hinge and Latch System

Learning Metalwork from Shumei Tanaka

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.