Metalsmith ’88 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

28 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1988 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Eleanor Moty, Pat Flynn, H. Charles Schwarz, J. Fred Woell, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Goldsmithing: New Concepts and Ancient Traditions in Jewelry

Lousiana State University Union Art Gallery, Baton Rouge

February 5-March 4, 1988

curated by Barbara Minor and Christopher Hentz

This invitational exhibition composed of works by 25 American jewelry designers gave the audience a perspective on the diverse nature of what is being done nationally in contemporary art jewelry. All of the work chosen displayed a contemporary use of traditional goldsmithing processes or the integration of modern technology. In an effort to represent the full range of art jewelry being made today, some pieces were limited production while others were one-of-a-kind.

The stress on contemporary uses of traditional materials was noted by Baton Rouge State Times-Morning Advocate reviewer Jean McMullan who wrote: "Pat Flynn of New Paltz, N.Y., uses a simple colored pencil to get the needed color in his jewelry, Kate Wagle of Mesilla, N.M., includes different colors of gold plate in her delicate pins. The combination of unrelated elements is one characteristic of Fred Woell's work. Thomas Mann of New Orleans also can be credited with a like combination of unusual materials as well as perhaps the first jewelry artist to incorporate collage in his work. Another new concept is to be found in the slightly irregular surfaces of enameled pieces—defying the tradition of the very smooth surface, Leonard Urso of Scottsville, N.Y., creates jewelry that emphasizes the material but also includes in his simple shapes faint images that emerge from the material."

Included also in the show was the work of Tom Lorio, Baton Rouge, LA, Colette, Berkeley, CA; Mary Chuduk, Tempe, AZ; Barbara McFayden, Chapel Hill, NC; Peggy Johnson, Philadelphia, PA; Els Herber NYC, David Peterson, W. Lafayette, IN; Randy Long, Bloomington, IN; Harold O'Connor, Taos, NM; Jamie Bennett, New Paltz, NY; Richard Mawdsley, Carterville, IL; Kathy Buszkiewicz, Cleveland Heights, OH; Michael Good, Camden, ME; Bruce Metcalf, Kent, OH; Mary Lee Hu, Seattle, WA; Claire Sanford, Cambridge, MA; Barbara Heinrich, Rochester, NY; Micki Lippe, Seattle, WA and the curators, Barbara Minor and Christopher Hentz.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Eleanor Moty

Perimeter Gallery, Chicago, IL

February 19-March 19, 1988

by Karl J. Moehl

This was a small, but enlightening exhibition of recent work by Moty. Five works were dated 1988, six 1987 and one each 1984 and 1983. All were sterling and 14k gold setting for polyangular cuttings of rutilated or tourmalinated quartz crystals, the sort of thing that has occupied the artist throughout the decade.

During the 70s, Moty worked in a variety of art metal forms, often involving photographic images, for circumspect, but nonetheless pop images. Her switch to her present work was a profound change. Always clever and technically flawless, she now turned toward perfection. An exercise of surprise and delight now became an endeavor toward absolute exactitude.

What happens is this: Moty takes pieces of quartz crystal that are "flawed" by a multitude of rodlike shapes of the metallic mineral's rutile and/or tourmaline. She cuts these in various faceted shapes, keeping in mind the random patternization of the rods, using a process evidently less easy than it appears. Next, she fashions the sterling setting, which, of course, sheaths the sides of the quartz, but thickly or thinly so, depending on compositional demands. This frame is then further enriched by appended elements, most often silver rods that correspond and react to the haptic rutile or tourmaline; rods within the quartz. Or the appendages may be knobs or more complex accretions—in this showing we find leopidilite, sapphire, topaz and, of course, gold.

Realizing the apparent method does not itself account for the effect, which is both simple and complex, intuitive and intellectual in its appeal, and seems most exactly to afford "cure joy" in the sense Brancusi meant it. This is definitive jewelry: stone and setting in faultless accord. Something precious, but with all sentimentality banished along with ceremonial function, worked to an end that seems beyond fashion or style categories-this is what Moty gives us.

This observer sees this work as miniature sculpture. The display here clipped the brooches—for that is what Moty calls them—to plexiglass panels held diagonally within plexiglass boxes. The light streamed through the near-colorless quartz, dramatizing the all-important rods, and caused the metallic surfaces to glow. It would seem that the effect would be lessened if the quartz were set against something opaque, or forced to conform to anything other than some idealized well-lit space.

Perfection, we must realize, gets mixed reviews. Witness the example of the Portland vase, reduced to shatters by unconscious revolt, or take those engineers who had railroad tracks laid close by the Taj Mahal. Even if one is not driven to attack Michelangelo's Pieta with a maniac chisel, perfection in any form is liable to fester a spot of irritation. Moty avoid or compounds such reaction according to one's viewpoint. Her designs confront the accidental in nature through her response to the rods. For the artist this provides an open-ended challenge and an unending theme. But, also, she entraps nature and thus makes it conform to the artist's will. Some might call this the essence of art. Indeed, let's call it that!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contemporary Metals USA III

Downey Museum of Art, Downey, CA

October 29-December 18, 1987

by Carolyn Novin

Downey s third national metals show, juried by Christina Smith, differed from the previous two in several ways. There was less color and brilliant colorizing of metals, less jewelry and fewer objects. But, in this case, less was quite a bit more: more use of patinas to signify age, more small-scale sculpture, more objects that attempted to express archetypal or subconscious content. Both jewelry and sculpture evidenced a preference for assembly over the shaping of a singular object. Fortunately, the individuality of the 98 artists and 118 works presented proscribed any neat categorization of this show, where many artists sought didactic rather than decorative effects.

Often the title of a piece acted as an essential component; some titles amplified what they named, as in Moving Brittle Nose, a rattle-headed lattice of patinaed copper strips by Claire Sanford, placed atop a shoulder-high pedestal Skit iddly it dot, the title of Daron Sach's pink, red, yellow, black and orange painted steel construction, was a verbal translation, with a Memphis accent, of its geometric units.

Other works, with ambiguous titles, were incomplete until the viewer, like a quantum mechanic, resolved the seeming disjunture. For example, Wild Thing, a silver, nickel, bronze brooch by Fred Scott didn't appear wild in setting or demeanor, so did the title identify the beast or the wearer?

Roger Snyder, and others, used metal and other materials for mixed-media constructions. Though anyone who has played with electricity would have left a visceral response to Snyder's Only a Means to an End, the dynamic power of this piece came from the juxtaposition of readymade photo mural, fuse boxes and plastic men, one literally "burnt out," sitting in for the fuses. The varied meanings elicited by form and materials heightened awareness of the potentials of human use and abuse.

Many artists made a small-scale tableaux to explore issues of humanness and humaneness, The Sport by Carolyn Dunn was a disturbing portrait, in the form of a trophy, of everyman's values, lineage and legacy. Bruce Metcalf enlarged scale for striking effect in his African Adornment pendant, a seven-and one-half inch square replica of a 35mm slide, hung from a camera strap. Metcalf completed the camera reference with photorealistic depiction, in metal, of a native African woman. Beautiful, but certainly uncomfortable to wear, it posed some uncomfortable questions about exploitation and the taking of images, symbols, even people, out of the cultures in which they have meaning.

While I saw "high-tech' materials and designs, a greater number of objects depicted the human form or represented the human spirit and experience, as in Donna Pioli's endearing biomorph Overturned. Julie Eamer's Cycladic Idols and Manitou by Tony Shaw evoked reconnection with our heritage from pre-technological cultures. Two brooding sentinels, Timothy Doyle's Old Guards, rose, like spirits made manifest, from the centers of their power bases.

Though their imagery could be deconstructed, it was personally much more rewarding to witness the stark confrontation between forged wrought iron and stone in Fred Borcherdt's Die Marker, to enjoy the multifoliate grace of Sue Amendolara's sterling perfume bottle and to appreciate the technical and material splendor of Mark Stanitz's gold brooch with zirconium cube.

lf art has no inherent meaning, and if we learn to see and to invest meaning with a system of gender and culture directed codes, then all art is didactic. This show successfully demonstrated that it is vital for art as it questions the givens, to be accessible but not clichéd, and to remember that beauty and humor, as well as "drama," have great educational potential.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dalya Luttwak: Japanese Patchwork

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

June 14-July 28, 1987

by Yvonne Arritt

With the current emphasis on economic competition, balance of trade and export-import quotas between the United States and Japan, there is one significant field that the Japanese have neglected, not even begun to explore: the use of jewelry as a form of cultural expression.

Perhaps it takes an international traveler with a discerning eye to recognize that omission, distill the essence of the country and translate it in tangible terms. Dalya Luttwak, who holds dual American/Israeli citizenship, has captured the spirit of elegant simplicity in her recent collection of 40 necklaces, pins and earrings.

"Japanese Patchwork" is the synthesis of images and impressions acquired during three visits to the Far East. In forms suggesting gates, gardens, kimono sleeves and sails, tea ceremonies and traffic patterns, her work reflects a mélange of past and present, at once delicate and static, yet colorful and bold, filled with complex harmonies. She identifies seasonal color schemes, employing 18k and 24k gold overlay on sterling in the keum boo technique with pearls, aquamarines and peridots for summer; oxidizes the silver for stronger contrast in conjunction with lapis, garnet and black onyx for her winter palette. Her strongest designs are reminiscent of traditional table settings or ingenious wrapping and packaging methods. In these, the trapezoidal gold appliqués echo and reinforce the objects' oblique lines, richly embellishing repeated elements. It is a harmonious blend of oriental ambiance and western sensibility; one wishes that there were a practical way to export these elegant hybrids and show the Japanese what they are missing.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

H. Charles Schwarz: Metal

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

September 1-26, 1987

by Roberta Floden

H. Charles Schwarz is a master technician. In each of his pieces, he uses an interesting combination of materials, including bronze, bone micarta, damascus steel, pewter, sterling, copper, gold and brass. His execution appears flawless. However, amidst an exceptionally high-quality display of metalsmith art at the Susan Cummins Gallery (including the work of Carolyn Morris Bach, Thomas Mann and Jaclyn Davidson), his jewelry, shot glasses and containers seem belabored and dry.

One of the more obvious problems with Schwarz's work is that it is heavily dependent upon a personal icon—the finely shaped head and neck of a water fowl—a slight variation of which he has repeated on every piece in the show. His shot glasses use this icon as a handle, the containers as a decoration and his brooches and bracelets use this icon soldered to a snakelike body made from a damascus steel coil. Schwarz's titles call attention to this focus: Mythical Bird Emergence, Crane with a Golden Heart, Bird with a Shimmering Recollection #2, Bird with a Sentimental Fascination #2, the "with" referring to a contrasting metallic construction stuck in the bird's beak. Unfortunately, the differences in decorative detail and shape that do exist—a scrimshawed micarta collar, a geometric tail, an incised or gold inlaid body, a "recollection" as opposed to a "fascinatjon"—neither caught nor held my interest.

Of all his pieces, this icon serves most effectively on the brooches. Here, against the background of a garment, the juxtaposition of a variety of metals, the differing shapes and the delicate details of each piece is dramatized. The brooches are also noteworthy for their latches, which are ingeniously and compatibly incorporated into the ornamentation. Another welcome feature is that each brooch comes with a small but sophisticated lucite stand that serves to display it when not being worn.

But this design has much less appeal in the bracelets. Between the bird's neck and the snakelike body, Schwarz has placed an unattractive intrusive element of asymmetrical copper. This element may work practically as a weight to keep the bracelet in place—which these pieces unfortunately require—but the variety of shapes and metals common to each piece makes the bracelet appear clumsy and disproportionate. This is compounded by another problem. Schwarz has created a design that is made from steel, and his bracelets are completely unadjustable. I was unable to get any of them over my normal-sized hand.

Schwarz's shot glasses are simple, unified and esthetically pleasing, but again, like the bracelets, the design is impractical. Made of textured pewter and echoing his former titles (Goose with a Golden Fascination, Crane with a Found Object), they sit bottoms up, and the bird's neck and head function as a handle. Thus, if you were actually to use this item, it could not be put down as long as there was liquid in the glass.

Schwarz's pewter containers are probably the least successful of his work. The containers themselves are candy-dish sized, three of the four having a reference to lids that do not operate as such. Affixed to two of these lids are, again, bird's heads, but the other two have a refreshing "mad dog-head" variation. Awkwardly sitting underneath each "lid" for balance is either a copper cone or a scrimshawed micarta knife. The pewter itself is textured, perhaps by roll printing, and covered with enigmatic symbols, scratches and bird markings. Esthetically their shapes and decoration leave something to be desired. But worse, I would be hard pressed to know how to use these expensive containers that would not trivialize them, Hair pins? Candy? Paper clips?

In the last analysis, Charles Schwarz takes no risks with his designs. I found no surprises, nothing unexpected. In fact, because the brooches and bracelets are so similar, it was difficult to distinguish one from another. Although he has mastered the techniques of metalsmithing, his pieces do not always flow esthetically, nor do most of them function easily. Schwarz operates from too cerebral a place (his idiosyncratic head/neck icon symbolizes this perfectly). I would guess that he is intellectually gripped by his mastery, and expects his audience will be as well. What I miss is depth, humor, passion and a stretching of the imagination. His craftsmanship needs to be put into the service of art so that design, function and decoration can merge to form a more unified work.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Metalwork '87

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

October 18-November 14, 1987

by Michael Monroe

The fourth biennial juried members exhibition of the Washington Guild of Goldsmiths represents their finest showing to date. The Guild, known nationally as one of the strongest regional organizations of metalworkers, is comprised of individuals whose earlier expressions in metal have come to fruition and are shown here in their mature form. It is because of the sustained efforts on the part of these artists that this exhibition manages to escape the mediocrity that characterizes most regional or local guild membership exhibitions.

Juried by Sharon Church and Jackie Chalkley, these 104 works by 34 artists encompassed many of the same esthetic issues that concern other artists working in metal, both here and abroad. A particular strength within the Guild, which is manifested in the exhibition, is the considerable number of individuals who produce high-quality holloware. The jewelers in the group continue to question the function and intent of their creations as they relate to the human body. While several pieces reflect jewelry making in the traditional sense precious metals, precious and semiprecious stones, filligree and pearls—others utilize new and unexpected materials such as titanium and niobium, plastic and painted wood, to forge new dimensions in their craft.

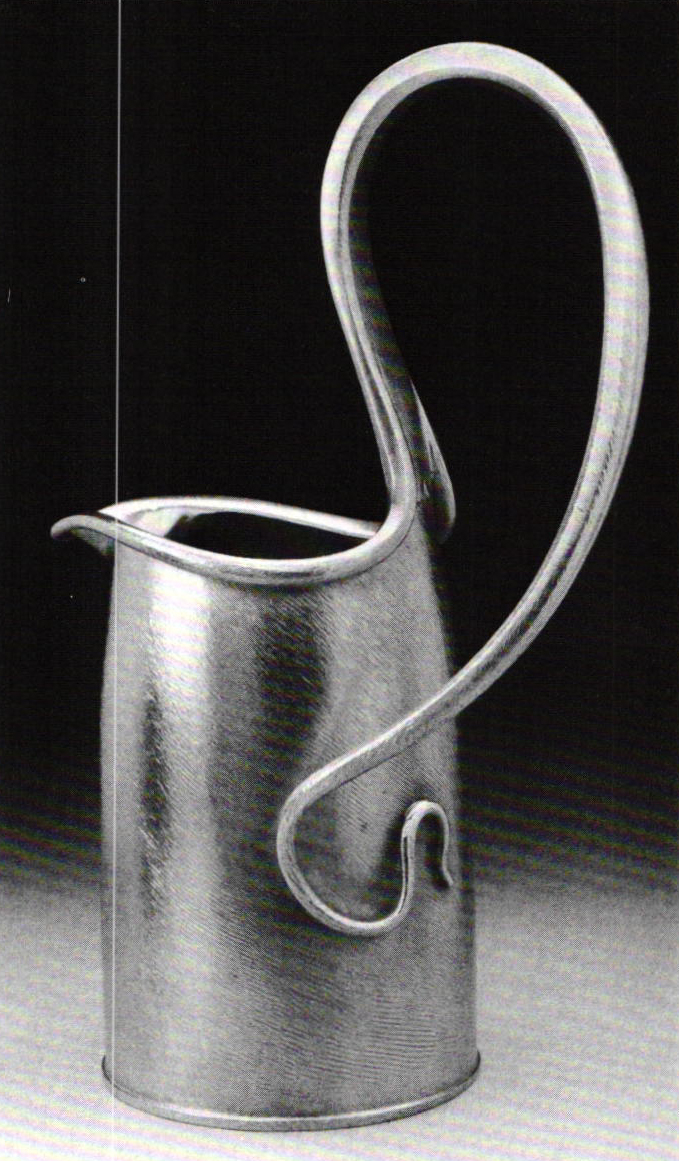

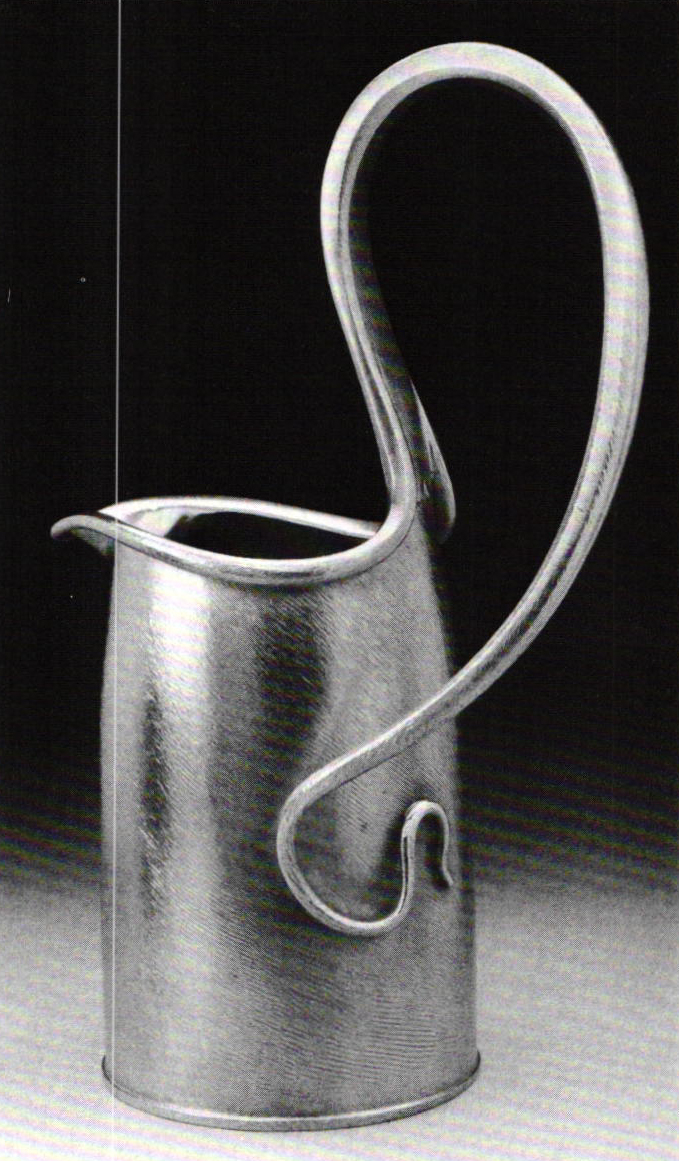

Fred Fenster continues his masterful handling of holloware in pewter with a dramatic creamer in which restrained tendril obediently follows the contoured lip edge before it sensuously whiplashes into a highly energized handle. In the table piece, Fetish for a Teacher, Barbara Grinberg achieves a richly patined surface that metaphorically suggests ancient wisdom contained within a central, enclosed dome. Emanating from the core are conduits from which strings of beads, in varying hues of turquoise stream forth suggesting a fountain of knowledge.

Yvonne Arritt's elegantly twisted silver band swirls around the neck of its wearer suggesting a metallic scarf. A roll-printed pattern of loosely woven gauze on one side creates a subtle but rich textural contrast to the reverse side of this highly polished and crisply articulated sterling collar. Using the unconventional jewelry materials of wood and acrylic paint, Betty Heald's series of Object Pins are considerably more successful when seen as a group than when separated into individual pieces.

Continuing with the bisected circle as a motif, Gretchen Raber's Necklace 62087 is a superb example of her exquisitely complex design sensibilities combined with matchless craftsmanship. The several pierced and superimposed layering of diagonally intersecting lines result in continuously shifting moiré patterns that provide infinite visual delights.

Merging the disciplines of holloware with jewelry concerns in the same piece is an idea that Betty Helen Longhi has successfully developed in her Bowl with Removable Brooch. The sweeping and twisting forms are highly stylized and catapult the viewer's eye to a dramatically placed amethyst at the apex of this sculptural form.

Dalya Luttwak's Japanese Patchworks #3 is a matching pair of pin and earrings. Luttwak achieves this sense of unity without resorting to reproducing the same design in different sizes. Each is a slight variation on the motif and each variation is appropriate to the function of that piece. Her subtle handling of a wide variety of materials and techniques on a small scale and her subtle use of gold epitomize the attitude of understated elegance.

A year's residence in Wisconsin, with its ice storms and frozen fields reflected in spectacular sunsets, inspired Komelia O'Kim to produce her strongest jewelry pieces thus far. O'Kim's pins Fanfare #1 and #2 show freely placed silver and gold fragments on a dramatically dark background. These fragments extend beyond the retrictive border of her fan shapes to suggest the powerful, expanding forces of ice in motion.

Winged Brooch II, fabricated by Barbara McFayden, is a very successful example of the integration of the champlevé enamel technique with precious metals. McFayden's restricted color choices are refined and sensitively keyed to the accompanying materials, thus providing complementary visual roles to the base metals that support the champlevé.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

David Didur, Recent Work

Prime Canadian Crafts, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

November 9-21, 1987

by Carole Hanks

The form and substance of David Didur's new work is classic, that is, classic in its approach to the idea of rules and models in esthetics.

Didur takes the constructs of Euclidean geometry and reworks them in a post-modern context. Fabricated shapes echo with geometric rules of construction. One is aware of edges of octahedrons, apexes of triangles and the generation of golden proportions. The structures are measured. The contours are clearly defined. Such clear structuring is the essence of geometry, and its Euclidean, that is to say, Greek base here represents the classical component of post-modernism.

The context of our post-modern thinking is classic, or at least classicist, and the orderly integration achieved by Didur's work represents his striving for classical harmony and form. Shape and line are weighted so that neither is subservient. Internal linear divisions are used to structure and balance sections and the sections are used to establish the proportions and harmony of the whole. Sides and surfaces are related to one another and are contained within each other. The integral structure of the resulting figure implies an underlying model, unseen, which is an intellectual construct of the perfect form.

The ancient Greeks developed the idea of geometric models. A Platonic model existed out of time and space and was approached by the artist of constructed forms through the mathematics of geometry. Geometry was the esthetic solution. Harmony of the parts was found in the proportions of each section to the whole and achieved through strict attention to formal and universal relations. Harmony was employed as an esthetic function. The goal was to achieve perfection the classic figure.

In Didur's work, geometry is still the esthetic solution, and harmonious proportions are still a philosophic goal. However, the idea of three-dimensionality alone does not dominate the work. Surfaces are given considerable attention with the use of patination and occasional applied material to create soft coloration and subtle pattern. They exude warmth, though the forms themselves are cooly ceremonious. The relationship of the two-dimensional surface to the three-dimensional figure is that of a dichotomy in which cerebral and sensual elements are mixed. The resulting objects are at once sumptuous, succinct and defined.

Didur packs volume tightly into space, which results in a monumental quality. His work, however, is not monumental in magnitude. It is scaled down with exacting refinement to intimate dimensions. Thus compacted, it commands a disproportionately great amount of visual space for its size, exuding strength and calm. Such qualities are a necessary part of the ancient classical model, though not always pursued beyond that time.

The difficulty of classicism lies primarily in inextricable attachment to the fashion of one's time. The idea of a universal model is always an interpretation, and perfection may only subjectively be visualized. The general assumption however, is that geometric form is universal and perfect. The intellectual exercise called geometry is the final harmony.

Didur is a very modern classicist. He allows the senses free play within an intellectual figuration. Intuitive and deliberate elements coexist. The shapes of his objectives are reasoned and mathematical, but their surfaces are sensual and organic with color and texture. Although the concepts of classicism are difficult and demanding and require filtering through one's own time and place, Didur's work suggests that the idea is still productive and provocative.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Container Untamed

Wita Gardiner Gallery, San Diego, CA

November 14, 1987-January 9, 1988

by Carolyn Novin

Containers are more than vessels of transformation and tools for everyday use; they are bearers of pattern and shapers of substances and ideas. In this show, container became arena, where artist as reservoir of skills and visions encountered viewer as holder of perceptions and associations. The objects displayed evidenced a widened notion of "container."

For example, jewelry often holds gems and, as necklace, bracelet, or ring, contains parts of the human body. Three of the four featured jewelers chose geometric design units. All used metal and other materials for their nonfigurative wearable jewelry. In Erosion Series Brooch. Donald Friedlich inverted the usual format of metal-holding-gemstone by setting a gold triangle as gem in an agate matrix. His strategic removal of material released the stone's inherent patterns and translucence. Jane Groover's rings and bracelets of silver and gold were precise and focused constructs, their high polish and refined settings accented by pearls, stones and reticulated areas. In contrast, muted angularity and patterned surfaces distinguished Jan Yager's necklaces of hollow, puffed ovoids, triangles and rectangles; these elements, unlike but compatible, functioned in harmonious interdependency.

Jamie Bennett preferred to assemble biomorphic shapes into wonderful silver and enamel brooches where each enamel was a vibrant medley of matte, flat colors including coral, turquoise, lilac and lime. The childlike spontaneity of Bennett's gestural enamel "jewels" counterpoised the technical sophistication of their containing and connecting settings.

Three artists reified the idea of container as vessel in vividly different ways. Lynne Hull highlighted the deep darkness of Ritual Bowl's center void by attaching a ring of black tubing Subtle patination, consistent over the spun copper and aluminum form, evoked images of ancient times and venerated use, while the play of opalescent greens and blues on Joan Austin's pouchilke Mermaid's Jewel Box embodied the ephemeral Loom woven of mylar, linen and wire, it referred, in its sensuality, to another container, the sea.

Helen Shirk's Black Tapestry, a moveable vessel-within-a-vessel, captured light motifs on its surfaces and through the intersecting lacunae of each bowl to make variable patina effects. Shirk also presented large shallow bowls rimmed by wide, horizontal flanges that engaged the surrounding space. All were patinaed with sprinkled or splashed designs. Small and enlarged versions of similar pattern and color, one on the flange, the other in or on the bowl, involved the eye in visual conversation.

In addition to metal, this appealing show comprised works in ceramics, fiber, glass, paint and wood. Resonances of color and synergistic interaction of various subjects, scale and personal styles made viewing it a delight.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thea Ernest

Sarah Doyle Gallery, Brown University, Providence, RI

January 28-February 18, 1988

by Mary Bell Howkins

The recent work of Thea Ernest reveals a sensibility clearly independent of the modernist tradition of crisp shining surfaces and reductive form. In fact, it gave this viewer the real if short-lived sense of having happened upon a cache of stunning early Aegean artifacts. The tension, entirely pleasing, between the useful purpose for which vessels are traditionally made and the purely esthetic role that Ernest assigns them, makes each piece seem destined for the summit of a gallery pedestal. And while this duality of role is paralleled in the sculpture/furniture of Richard Artschwager on a much larger scale in another realm of the current art scene, here diminutive size, purity of form and carefully orchestrated patina resonate a kind of archaeologizing presence that most of us only know via a museum context. There, the once-utilitarian vessel is permanently de-utilitarized, and thoroughly estheticized, for the benefit of a modern public. Ernest, consciously or not, incorporates a museum-goer's eye into the very conception of her pieces.

Obvious from the start is that the artist values color instead of reflection in metal, as well as intimacy of surface. This preference has in part determined her choice of copper as a favored material, rather lowly in the hierarchy of metalsmithing, yet remarkably versatile and easily pushed to transcendent stages Fruit Bowl plays a rich, multileveled patina through a subtle tricolor range from base to bowl. At each stage the dominant color is but the prevailing hue in a complex building of patina using deliberately low-hazard chemical processes (Ernest's longstanding concerns regarding hazard reduction have been spurred by recent findings on accelerated mortality rates among Rhode Island jewelry workers.) The shape of the bowl and supporting stem are elegant and simple, but subtly askew. A repealing convex scallop motif stretches, even lurches, in an understated, almost drunken humor not found in any other pieces, yet characteristic of the show's diversity.

Hinged Disk, as well as several double-shelled bowls, reveals Ernest's fascination with decorative mechanical seams. These are usually assigned a strategic role in surface design, and color often assumes a sudden phosphorescence when it encounters them. The Disk, a wide and low-lying vessel, consists of two convex hammered disks joined at the outer edge by a coppersmith's hinge. A ring of wire passes through alternating tabs cut from each surface. The circular expanse of rich patina, predominantly blue with copper highlights, along with the simply patterned seam are ultimately governed by an implicit geometry. Yet is only implicit, since the subtle rising and falling of surface and seam, the planned deviations from geometry, reflect the natural order of things. Underlying the piece's easy elegance is a careful observation of nature's superb sense of shape and fittings.

While the cactuslike shape of two standing vessels in the show seems too literal, despite exquisite painterly surfaces or imaginative interlocking seams, Boat is certainly the most lyrical and memorable work of all. With utter simplicity Ernest has succeeded in implying within the confines of the boat itself the presence of the entire sea on which it rides. The result is an evocation of myth, of voyages made for reasons of passion or honor, a medium wholly transcended. All of Ernest's work suggest a rare balance, a joining of coppersmith's craft and a refined esthetic sensibility. Deepened by an understanding of the historical and the natural it is thoroughly post-modern.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Alexandra S. Watkins and Nancy Michel

Body Sculpture Gallery, Boston, MA

October 9-November 4, 1987

by Vincent Ferrini

Alexandra Solowij Watkins and Nancy Michel's work is earthy, yet elegant jewelry in 18k, 22k and 24k yellow gold. Many pieces are of intricately worked gold alone, expressing natural form and texture, while others are set with precious stones or a variety of freeform, partially cut and polished or uncut, unpolished semiprecious stones, such as opal, tourmaline, beryl, lapis, jade and agate. These two distinctive goldsmiths, proprietors of the tiny, exclusively located Atelia Janiye in Boston, are regulars at Body Sculpture. And their current collection is not self-consciously avant-garde but rather a confirmation of many collective years of creative and technical development during which they have never depended upon stylistic flashiness or trendiness.

Their art, although sometimes quite bold and strong in design and form, is softened and unified by consistent use of high-karat golds, subtle, matt surfaces and intriguingly delicate, thin-walled constructions. Neither artist uses casting to achieve form; instead, they rely upon "puffing" the thin metal into soft-looking rounded or angular volumes via their skillful repoussé and folding techniques. They add subtle color changes with appliqués of 24k gold on 18k, and pickled surfaces against lightly brushed ones, a perfect example of which is Alexandra's elegant neckpiece. It glistens softly, a confection of golden bons-bons fit for a queen. Nancy, on the other hand, using similar techniques, adds large, dark triangles of softly polished black jade to her neckpiece, thereby removing her creation from the palace drawingroom to its proper place in the palace garden amidst the carefully tended, river-washed stones; decidedly oriental in feeling.

Both women readily admit to and are grateful for the lasting influence from years of working with the late Miye Matsukata, whose distinctive jewelry incorporated a delicate oriental perspective. Miye's intensely personal vision is certainly not what Alexandra and Nancy are trying to re-create. They have, instead, allowed the influence and insights of Miye's lifetime of making paeans to nature to wash over them in a benevolent wave, absorbing that which appeals to their individual creative sensibilities.

Even though they share a technique that unifies their work, at first glance, upon closer observation one readily sees important differences. Alexandra's design orientation is more abstract and less light-hearted than Nancy's, as evidenced by the two pairs of earrings. Although both artists are having fun making "pairs" of earrings that do not "match," Alexandra makes powerful microcosms of craggy rocks with watery blue boulder opals, while Nancy plays with the stone and water theme in the form of large, fat, "stone-fish" with mismatched, blue boulder-opal tails. Nancy's sense of humor bubbles to the surface of many of her creations.

One could go on evaluating the differences and similarities of these two engaging artists, especially since they both passed through the metals department of the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts but did so about 14 years apart. While major changes took place at the Museum School in those intervening years, and the backgrounds, lifestyles and experiences of the two women are quite different, their work is very close in general feeling. It should be fascinating to watch the continued development of these clearly outstanding artists.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Profitable Jewelry Design and Repair

Getting to know Mark Schneider

Fads and Fallacies: First Impressions

An Interview with Milt Fischbein

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.