Metalsmith ’89 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

19 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1989 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Gijs Bakker, Curtis LaFollette, Carrie Adell, Gry Eide, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Helen Drutt Gallery Philadelphia / New York

by Toni Lesser Wolf

In preparation for this report on Philadelphia gallery owner/director, Helen Drutt, I had done a fair amount of background research - thumbing through past articles in Philadelphia newspapers and periodicals, national and international publications, etc. But it wasn't until I spent a day at her recently opened New York gallery observing first-hand, this "eggbeater" of a woman (as one writer so aptly described her) that I truly began to understand why she is so well respected by artists, scholars and patrons.

During my visit, I watched her patiently approach prospective customers. She is a born teacher and believes it is her obligation to educate her clientele. "It is the responsibility of the art dealer," says Drutt, "to complete the creative cycle begun by the artist; to be articulate and to communicate the historical context and formal aspects of the work to the public." I also witnessed her irrepressible joy when some of Peter Skubic's jewelry students, visiting the United States from Cologne, stopped by the gallery just to present her with a waterball from a town in Germany - these toys, with "snow" floating above plastic land and cityscapes, being her, not so well-known, collecting passion.

Nothing escapes her! Her mind is a vault of facts and anecdotes relating to post-World War II craft, especially since the 1960s. Although her galleries offer works in a variety of media, our concern here is solely with contemporary jewelry. "Initially my reasons for owning them [jewelry] were in order to promote my newly born interest in modern crafts. It was logical that no one could carry a vessel or chair into a meeting. Wearing a brooch was no different from being a living billboard. Jewelry acted as a catalyst for questions and queries from museum directors, curators, acquaintances, students and strangers."

In 1965, she visited Philadelphia jeweler, Stanley Lechtzin (who was then, as now, teaching in the metals program at Tyler School of Art) and was impressed by a nearly completed brooch that incorporated the esthetic qualities of painting and sculpture. The following incident is an example of Drutt's success as a walking advertisement for modern, handmade, American jewelry: On a subsequent trip to Dublin, Drutt met Graham Hughes, then Director of London's Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. After admiring the Lechtzin brooch she was wearing, Hughes invited Lechtzin to have an exhibition at Goldsmith's Hall.

In 1967, she become a founding member and executive director of the Philadelphia Council of Professional Craftsmen, an organization comprised of 30 artists affiliated with the faculties of Philadelphia art colleges and universities (in addition to those who maintained independent studios). She remained in this unpaid position for seven years, during which time she organized many exhibitions, including the first David Watkins/Wendy Ramshaw exhibition to be held in America.

In 1973, she accepted a faculty position at Philadelphia College of Art to teach the first course in the history of modern crafts and in February 1974 opened the Helen Drutt Gallery. Among the jewelers represented in its inaugural exhibition were Amy Buckingham, Toni Goessler-Snyder, Stanley Lechtzin, Eleanor Moty, Alben Paley, the Pencil Brothers, Olaf Skoogfors And J. Fred Woell.

German jeweler, Claus Bury's extraordinary influence on American jewelry of the early 1970s has been generally acknowledged. The impact of his 1973 lecture tour, to metalsmithing programs across the United States, cannot be overestimated. Bury had visited Lechtzin and Skoogfors in Philadelphia and stayed at Drutt's home before embarking on this tour. In 1982, as director of the Art Gallery at the Moore College of Art, Drutt mounted a major exhibition of Bury's work, which included site sculpture, metal drawings and technical information (translated from German), as well as jewelry.

What Drutt offers in her galleries is a broadly discursive landscape of contemporary jewelry. It can be playful (Lam de Wolf, Gijs Bakker), structural (Eva Eisler), minimal (Giampaolo Babetto), organic (Pavel Opocensky), socio-political (Woell, Bruno Martinazzi) or primitive (Breon O'Casey). It can applaud technique (Francesco Pavan), be narrative (Manfred Bischoff) or just plain elegant (Max Fröhlich). Mostly, she is interested in the quality and originality of unique ideas - the artist's vision.

She feels the work of the 1970s, greatly influenced by Paley and Bury and their experimentation with nontraditional jewelrymaking materials, has evolved into a renewed interest in precious metals and gemstones. This occurrence, she feels, is due to three factors: the reconsideration of permanency in jewelry the dangers of working with toxic materials and a reaction to minimalism. As a result, artists seem to be making decorative and ornamental statements again.

Drutt is exceedingly optimistic about the future of jewelry. The private collector is the key to the survival of this art form, she believes, and, little by little, she sees jewelry entering the fine art mainstream, the way ceramics and glass have done already.

The crucial point about Helen Drutt's art gallery which shows handmade craftwork, is that it is just that - an art gallery. There is no hierarchy of forms. Functional and nonfunctional works, paintings, sculptures, textiles, vessels and jewelry coexist comfortably and even complement one another. Sculptures by Pavel Opocensky and Bruno Martinazzi are displayed alongside their jewelry as are paintings and jewelry by Breon O'Casey. Jewelry to Drutt, is simply portable art, scaled to the human body.

The Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia just celebrated its 15th anniversary, January 28 - February 24, 1989.

Toni Lesser Wotf is a jewelry historian, lecturer curator and writer living in New York.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Curtis LaFollette - Holloware

Hughes fine Art Center Gallery, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND

February 27 - March 10, 1989

by Tony Kiendl

The imposing figure who created these delicate, curvaceous teapots relishes paradox. As LaFollette admits, "It is a fundamental principle of my existence that I love things that appear to contradict themselves but are really rational - that really have this rational base, but yet they seem to be either emotional or totally random in their existence." He believes that contradictions consistently do not appear in the holloware, but they do. Another contradiction.

The pieces in the exhibit are mostly sketches - many created to reconstruct and then solve problems encountered by his students. This factor together with the informal and open presentation are welcome in the academic setting of the gallery, as they make it easy for LaFollerte's personality and beliefs to be readily understood.

LaFollerte's conical, pointed Teapot #21 is threatening. Functionally, the vessel embodies the spirit of a Japanese tea ceremony - harmonious, tranquil, contemplative. Simultaneously, by its shape, it juxtaposes the peaceful domesticity of the teapot with the violent potential of a sharp weapon.

LaFollette makes song of this struggle between sharpness and gentleness, peace and violence, yin and yang. This repeated study of contradiction is the most intriguing aspect of the exhibit. The contradictions found throughout the show force the viewer to re-evaluate the relationship between peace and violence, art and craft, reality and fantasy.

The artist's Dadaist fantasies are realized in a series of three Euthanasia Cups. These cups, made from metal and bone, heighten the underlying study of organic and inorganic, archaic and contemporary. When viewed with the neighboring teapots, another paradox develops. The viewer is forced to consider objects for daily pleasantries with objects for dying - all in one breath. One gets a sense of the contradictions not adding up, but rather squaring and then cubing.

Tony Kiendl is an artist and writer living in Grand Forks, ND.

Jonathan Bonner

Heller Gallery, New York

April 1 -23, 1989

by Vanessa S. Lynn

Since the early 1980s, Jonathan Bonner has embraced the weathervane as a sculptural analogy and has been honing it with a Minimalist's hand ever since. At their best, past vanes capture the essential linear gesture of Bonner's figurative subjects. Whether it be a crescent bean, a man-o-war or a zoomorphic fantasy, Bonner inevitably seizes the core of his model in a spare, yet spirited graphic rendering. As the vanes became larger (from nine- to 14-feet high, on average), these space drawings swing outdoors like animated streaks against the sky.

The latest pieces call to mind Brancusi's work, not as much for their pared-down gesture as for the way both minimize the sculpture/base dichotomy. Bonner's earlier weathervanes were a tripartite copper figure, support rod and incidental stone base. Now, in his best works, he often eliminates the vertical rod and brings the granite base up to where it becomes part of the sculpture's composition, maintaining the pivot necessary for the vane to function. At the same time, the arm, with its array of sail-like elements, descending in size from the fulcrum, projects upwards and diagonally from the base. Bonner's sensitivity to material densities, to complementary color and to the juxtaposition of movement and stasis marks significant Progress in his ability to achieve a sculptural totality.

Nevertheless, Bonner has not yet exhausted his fascination with the expressive possibility of line in space. Five wall-mounted pieces employ a single, simple, animated form, suspended by a careful configuration of prefabricated metal cable (bronze or stainless steel). Here again, the support is integral to the totality, as when a lithe copper right-angle stays aloft by a symmetrical arrangement of cable. Seen head-on, the piece, aptly titled Moose mimics the animal's muzzle, and the cable configuration unequivocally describes its unique antler profile. Other works in this series use colored wood for the suspended element, but the material difference, in contrast to the weathervanes, is of secondary importance as the descriptive capabilities of line remain paramount.

Vanessa S. Lynn is a writer living in New York.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

David Watkins

Contemporary Applied Arts, London, April 7 - May 6

Helen Drutt Gallery, New York, June 1 - 30, 1989

by Deborah Norton

David Watkins's series of rigid neckpieces all begin with a flat, circular collar, which is then not so much adorned as explored. Using circles, lines and cogs, he repeats these elements over and over in various combinations and permutations, enhanced by a sensitive choice of materials and surface treatment. For instance, in Seeker, made of black Colorcore, the outer edge of the circular collar forms a cogwheel.

The exact design is repeated in Matrix l but this time done in brass. In Inversion 2, the cogs are on the inner edge of the neck collar and the material is Colorcore covered in gold leaf. He takes a similar approach with a set of neckpieces based entirely on circles. In Torus 280 (T1), the collar is pierced by a single ring of small circular holes. He has made this piece in untreated titanium, which catches the light and gives off soft shades of blues and grays. He uses the same motif in Torus 280 (T2) but, in this case, there are two rings of parallel circles and he has slightly anodized the titanium to subtly enhance the colors. And so it goes with the next piece in gilded brass having three rings of circles and another, exactly the same but made of untreated titanium. Each piece seems to complement and reinforce the one beside it and together they make for a very thorough investigation of a severely restricted vocabulary.

This minimal repetition is what gives these pieces their spiritual presence - the fact that the viewer is left to contemplate in depth that which is most basic without being distracted by the superfluous or superficial. Consequently, the most successful piece in the show is also the simplest. Matrix IX is a narrow, circular collar with a horizontal linear strip attached at the top and balanced at the bottom by a similar vertical strip. The extreme austerity of this minimal design is softened by the faint scratches of the hand-finishing process left on the gilded-brass surface. Reminiscent of ancient religious symbols such as the Egyptian ankh or Incan geometrics, it has an undeniable mystical quality.

These elegant neckpieces, when worn, create an unexpected antithesis to the softness and flexibility of the human body because of their rigidity and machined precision. But when displayed in cases, the objects are forms worthy of contemplation in their own right, giving the viewer a chance to leisurely ponder their hidden mysteries.

Deborah Norton is a contributing editor to Metalsmith, living in London.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Christina Smith

CDK Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

November 30, 1988

by Carolyn Novin

Bold scale, representational imagery, skilled fabrication of sterling silver and acrylic, all describe Christina Smith's new jewelry. Previously, Smith fashioned acrylic into miniature objects; here, she used sterling for details and acrylic as a structural color.

More open compositionally than her earlier work, these pieces integrate narrative content within formal designs. For example, because the dog, house and burglar in Tax Deductible are not in correct proportion, the viewer feels threatened by the intruder, who appears larger than one's home.

As in a freeze-frame, each brooch depicted a specific moment in an event or relationship. While creating focal depth with size variation, overlap and perspective lines, Smith undercut the illusion in Flipper Did My Wash by adding conspicuously flat figures. Such interaction between volume and flatness maintained tension. Each brooch was both kinetic and static; animated characters who gestured, perched, slouched or strode, plus the actual movement of a tiny washboard, a pair or shears or a circle maze dangling from its chain contravened the square-wire framework around which they were arranged.

Compared to other narrative jewelry and to Smith's bolo ties and bracelets in this show, her brooches felt contemporary because of their topical subjects. More to the point, they embodied the disturbing union of emotional occasion and cool detachment pervading contemporary society. For, despite their familiarity that involved the wearer as part of the narrative, the formal effect was of control, balance and distance. This paradox persists in my mind as an unsettling aspect of the work.

The brooches, each given a descriptive title, told their stories with incomplete information and featureless actors who, caught in a spotlight, shielded their privacy with reflective, sparkling surfaces. Perhaps a shadow play, the story is known only by the poses and relationships of silhouettes, as Christina Smith's tantalizing scenarios remain illusory.

Carolyn Novin is a metalsmith and writer living in Los Angeles.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lisa Gralnick

CDK Gallery, New York City

April 4 -May 6, 1989

by Jill Slosburg-Ackerman

Lisa Gralnick's new, large acrylic brooches and bracelets are difficult. Compared to her earlier pieces, which are more straightforward and seductive in representing "black" notions of architecture and weapons, the latest work is enigmatic in its varied allusions to industrial-scientific artifacts, decorative motifs and pure geometry. As fragments, they don't seem to be totally resolved. Somehow, these pieces don't make decipherable, communicative compositions, perhaps because they are more ambitious in their deviation from pure minimal forms.

Her customary use of black acrylic saturates her forms literally and metaphorically with an irony that underscores the nonprecious quality of the material. What is unexpected, however, is the sheer lightness of the big brooches (1″ and 6″ tall) and bracelets (3/2″ cubed), extending the limit of what is wearable without physical discomfort or risk to the wearer's clothing. The work forces us to ask what is the difference between jewelry as small sculpture and jewelry as wearable decorative objects, between jewelry as small objects and sculpture in general.

Gralnick's allegiance to jewelry is illustrated by each brooch's abrupt flat back. The pieces meet the body decisively, invoking an unavoidable dynamic between wearer and object. They complete each other, magnifying the vast differences between organic and industrial forms. Gralnick's jeweler's scale, too small to have the presence of sculpture, emphasizes the public nature of jewelry as decoration, yet large enough to invite dialogue in the suggestion of badge or emblem.

The conflict in Gralnick's work lies in the provocative ideas in her visually unresolved objects. In defense of these "uneasy" pieces, there is a compelling sense of exploration and redefinition. In its spirited severity, this work rejects conventional assumptions and offers a courageous departure.

A 16-page catalog of the exhibition, including color illustrations, with foreword by Henry P. Raleigh and text by Michael Dunas and Sarah Bodine is available for $10 from Garth Clark Gallery, 24 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019.

Jill Slosburg-Ackerman is a jeweler and sculptor and professor of art at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gry Eide

Galerie RA, Amsterdam

April 22 - May 31, 1989

by James Evans

Gry Eide is, for me, one of the most "Norwegian" of the Norwegian jewelers. She takes her inspiration from rambles in the countryside, folkloric objects and traditional Nordic architecture. Never rushing from one style to another or one material to another, she remains true and consistent to her vision, which may be termed poetic. As she writes in the catalog: "The making of jewelry is to me a time-consuming process. The pieces are the fruits of associations which are awakened throughout their creation. It may be the mating dance of a bird in the forest (some of her pieces are titled Birds Jewel I or II or a pitch-black stave church dripping from the spring thaw, a time-worn painted door, fairytales and sagas, caterpillars and butterflies, old tools or a frostcovered barn door."

There are times when catalog statements like the above, leave me rolling my eyes in antiromantic revulsion but, in Eide's case, the work displays the sincerity and sensitivity implied by the catalog notes. The pieces are beautiful to touch, behold and consider. They are elegant and obviously made with utmost care, skill and love. I did have reservations about one or two pieces, especially Urban Fruit, which leaned a little to the kitschy side in its use of lime-sparkled, industrial plastic, an uneasy companion to the cane and natural materials elsewhere in the piece. They also had the effect of slightly subverting the quiescence and rigor of the more harmonious works.

But with most of the work of high standard, these are rather small quibbles. The viewer was offered works of excellence and originality. A particular standout was Tool III, a handcarved, painted shoulder object, which displayed finesse, superb construction and an instinct for a found wood form, which, when transformed by the maker, became a simple, elegant, respectful and clever work.

James Evans is Principal Lecturer and Course Leader of the Wood, Metals, Ceramics and Plastics course in the Department of Textiles and Three-Dimensional Design at Brighton Polytechnic in England.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carrie Adell: On the Rocks II

Alianza Gallery, Boston, MA

May 12 - June 24, 1989

by Susan Barahal

Adell's current work is a collection of metal "touchstones." Historically, a touchstone is a black stone used to test the quality of gold. Throughout the years, the word touchstone has come to stand for any criterion used in assessing value. Adell's touchstones, which represent small pieces of the earth, are, perhaps, reminders chat we should not lose touch with what is truly valuable.

Each of Adell's rock forms is meticulously fabricated by combining several layers of colored metals. The alternating colors are stacked, sweat-soldered, cut and rolled until the desired thickness of the "sandwich" is achieved. This process is repeated several times in order to expose the many colors and patterns created by the layering and rolling. Known as mokumé, this Japanese method creates a woodgrain appearance traditionally used in the decoration of tsuba, or sword guards.

Adell's choice of technique is ideally suited for her touchstones. The inherently organic pattern of the mokumé relates to the shapes of the rock forms. Swirls of sterling silver, copper, gold alloys and bronze form fluid patterns over the surface. Adell also incorporates the Japanese technique of shakudo, a black patina on the alloy of fine gold and copper. A Japanese influence is also evident in Adell's designs, as many of the rock forms have markings recalling the graceful strokes of Japanese calligraphy.

In her Inclusions and Rockfall earrings, the rock form is divided by a crevice bursting with "pebbles" of freshwater pearls. The pearls cascade from the "rock" in a three-tiered fall and are delicately connected to it by a faceted and bezeled yellow diamond. Pearls in shades of pink, gray and gold echo the colors and shapes of the mokumé-patterned rocks, from which they seem to emanate.

In a choker, Adell joins the strings of pebblelike pearls with two gold rocks. While functional, this organic clasp is an integral part of the overall design. In fact, the rocklike closure is the focal point of the piece. The rich, shakudo patina of the background provides a vivid contrast to the overlays of white and yellow gold that are complemented by pearls in lustrous shades of blue, purple and gold.

Many of her designs incorporate removable beads, encouraging the wearer not only to change colors and patterns but also to add additional touchstones. In this manner, Adell reminds us of the ancient belief, in which the quantity of one's amulets reflects the degree of one's power.

Sasan Barahal is the Decorative Arts Editor for Art New England magazine and teaches are in the Boston area,

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rachelle Thiewes

CDK Gallery, New York

March 7 - April 1, 1989

by Sue Amendolara

Rachelle Thiewes's jewelry emanates ritualism. Several spicula, varying in size and surface treatment, are used in each piece. The repetition and overlapping of the spicula produce visual rhythm as well as physical movement reminiscent of African tribal adornment. Thiewes's work, likewise, relates to the idea that messages of sexuality, availability, status and seduction are transmitted by wearing jewelry. These "tribal" pieces are boldly oversized, demanding the endurance of the wearer and confronting the viewer at first glance. And although large and aggressive, the work appears graceful and elegant on or off the body due to Thiewes's sensitivity to proportion.

The pieces are predominantly sterling silver with a variety of surface treatments: polished, matt, patinated black or with "mottled stripes" of black and white. Detailing is achieved by using 18k gold rings and, in some cases, 18k gold cones and patterned slate.

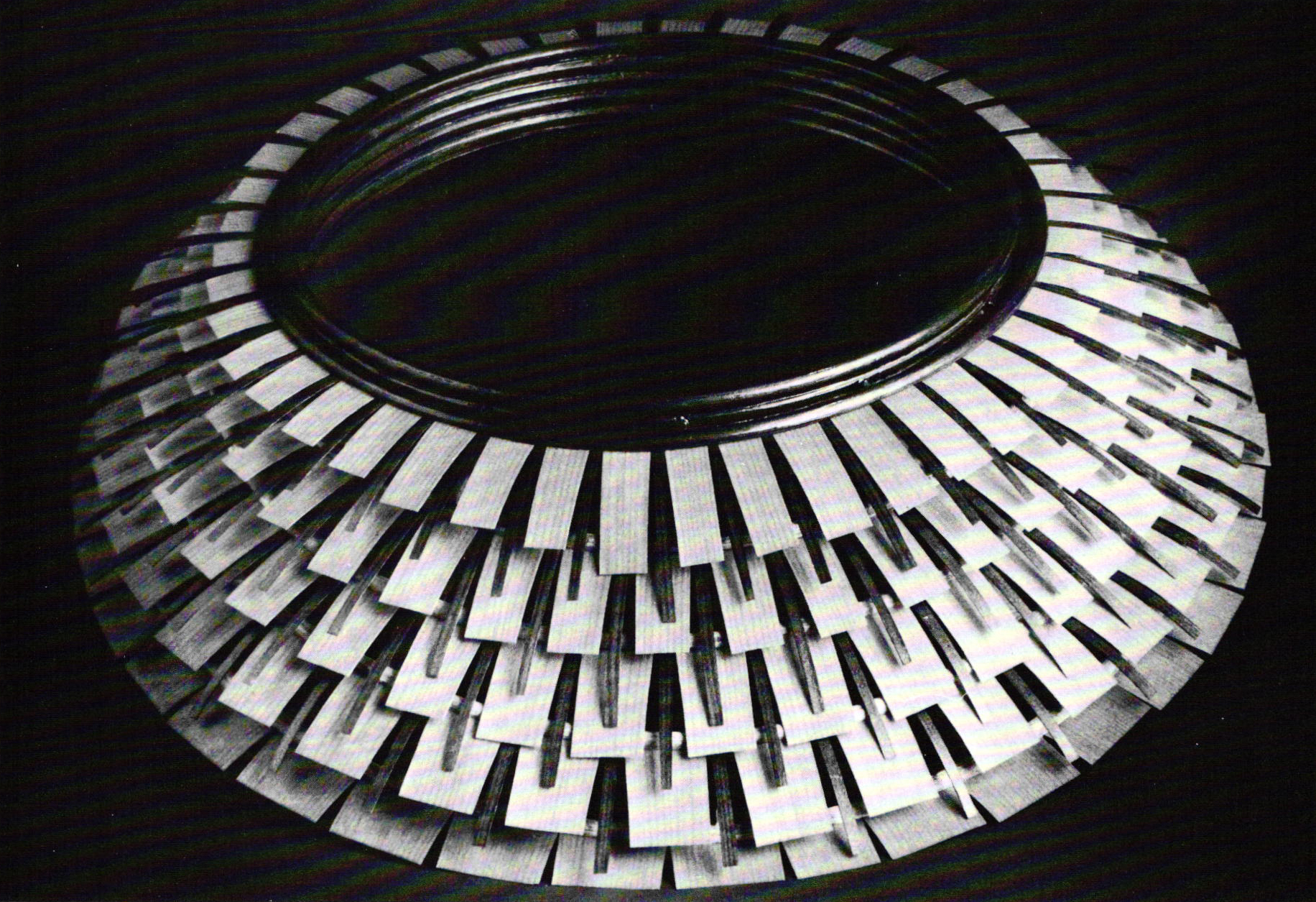

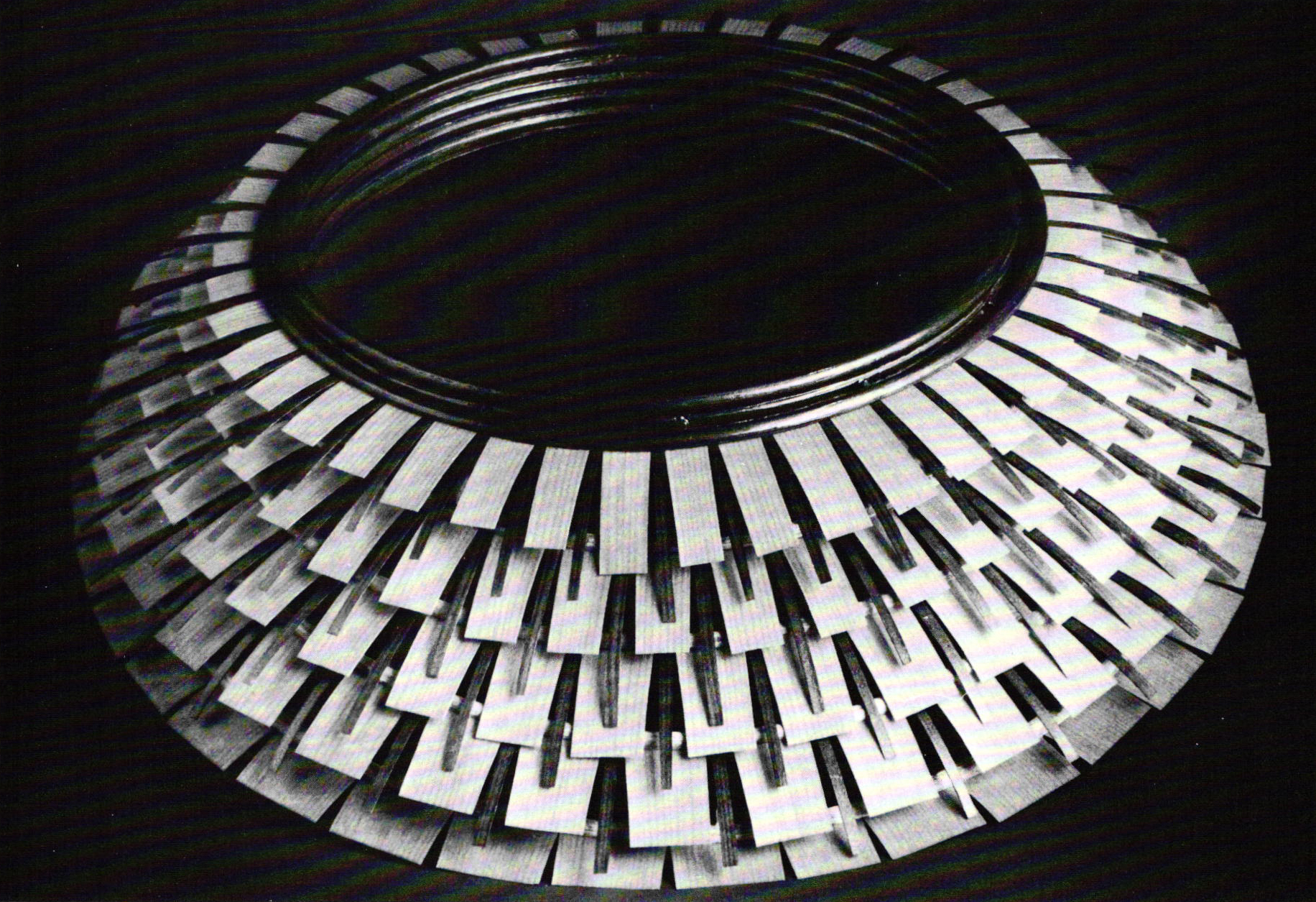

The necklace Echoes and Rhythms of Trane, the highlight of the exhibition, exudes spiritual energy. The use of sterling silver for the spiculum, patterned slate discs and gold rings strengthen the tribal and ceremonial feelings. Countless tapered tubes occupy its three tiers and give the necklace a wonderful tactile quality that allows it to appear light and feathery when worn. Thiewes seemed obsessed with this necklace because each detail is intricately worked out.

Two of Thiewes's bracelets, also untitled, are similarly designed with a large circle and various spicula connected slightly above center, decorated with gold and slate details. Exhibited on the points of the tapered tubes, they appear to be standing guard as powerful statements of protection and security.

Sue Amendolara is an artist living in New York.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Fred Fenster: Function and Ceremony in Pewter and Silver

GZ Art+Design Spots 2007 2

The Jewelry of Michael Zobel

Thomas Gentille: Performance of the Ephemeral

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.