Metalsmith ’89 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

25 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1989 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Brent Kington, Keith A. Lewis, Eva Eisler, Rezac Gallery, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Brent Kington: Cruciforms and Crosiers

Hodges-Taylor Gallery, Charlotte, NC

September 1988

by Jan Brooks Loyd

Brent Kington's vocabulary, over the years, has maintained a visual and emotional relationship with fantasy, kinetics and anthropomorphic expressions. His earlier weathervanes offered linear compositions exemplifying his inexhaustible affinity for figuration, fluid kinetic subtleties and the direct, expressive physicality of forged iron. From an interest in African body paint, Kington's figures have often simultaneously embodied refined, archaic coloration and ironic jocularity. The evolution of dense, painterly surfaces has accompanied this serial development bestowing on forms rich, archaeological references.

During September 1988, Hodges-Taylor Gallery, Charlotte NC hosted "Cruciforms and Crosiers," a solo exhibit on of nine figurative compositions from a new series of sculptures. This fresh body of work represents the filtering of more recent influences and experiences (notably, a three-month teaching/travel sojourn in Italy) and suggests a starting shift in the emotional and psychological characteristics of Kington's anthropomorphic forms.

One is instantly struck by the shift from the characteristic horizontal and kinetic function, so dominant in previous work, to a distinct vertical orientation implying expressive strategies beyond purely formal consideration. These figures no longer demand interactive forces yet are insistently dynamic via optical tactics, as the handling of color allows gestured append ages to offer complex illusions of movement within static, volumetric spaces. Upon an initial encounter, a reductive, "Giacomettian" dimension characterizes much of the work. These appendages form subtle, cruciform shapes as legs cross the pelvic element where a stele pronounces the vertical. Rectangular flags, and collage patterns often adorn the form at its hips, where the primary material volume appears. In some cases, hip sections are expressed as the flared laws of blacksmithing tongs with reins, completing spindled legs, poised on a three-tiered base. The bases serve to further suggest ascension figures holding promise of levitation and magical spectulation.

The more intimately scaled figures host a rich surface. Dense and seductive, these penetrating surfaces, through which the forged texture is evident, occasionally spark with patches of iconlike gold foil. However, it is the transfigurative quality of these human forms that implies an intense introspection absent in Kington's earlier work. These intricately surfaced, minimally proportioned figures cast a contemplative atmosphere, producing an aura of the sacred. These sculptural suggestions are at once reverential and emblematic of the flesh. Amidst a disordered, unstable world, the search for balance is implied in these confessional and self-critical efforts. These are, perhaps, risky implications to pursue given prevailing cynicism toward the therapeutic value of contemporary art.

Keith A. Lewis: Works an Metal

The Blue Moon, Rehoboth Beach, DE

September 5-October 2, 1988

by Betty Helen Longhi

In his first solo exhibition, Keith Lewis presents a series of superbly crafted pieces that address abstract concepts as well as social and even sexual issues. In his statement Lewis says, "In this culture jewelry has tended to be decorative—without stated content (except perhaps the peripheral content of ostentation). Producing jewelry which makes serious artistic statements or which seeks to prompt a jolt of recognition or reaction in the wearer is, as yet, a radical goal."

The work is divided into three categories. The first is a series of abstract brooches ranging from very simple linear designs to complex geometric studies. Most notable are the Swedenborgian Universe pieces, which exemplify his early exploration into the esthetics of good jewelry design. Based on the concept of an ordered, heavenly hierarchy, they are geometric progressions of concentric circles and spheres.

The second category of work deals with jewelry as a painterly medium. Using married-metals techniques, Lewis creates a group of miniature pictures. In these, the graphic elements float within a black background. They are subtle, abstract studies with a hint of deeper meaning. The pieces are "framed" as a reference to traditional two-dimensional art; but the frames are not continuous, instead they move into the design or open to allow the design to move through and beyond the frame. The imagery continues to the back so that for the wearer the piece becomes a three-dimensional whole—part of which he can choose to share or keep private.

Lewis's most powerful statements are found in his figurative pieces, which comprise the third category. This is the work he finds most challenging—communicating in metal the inner workings of his mind. Some of his figures send messages of hostility and aggressiveness, while others gently communicate more subtle emotions including sadness, confusion or loneliness. Through these figures he addresses issues such as sexuality, social interaction and death.

Lewis has strong feelings concerning sexual issues. He has come to feel that society's traditional sexual roles are limiting, offensive and dangerous. By challenging these roles through his work he hopes also to challenge the system. In Dancing Man with Dancing Genitals, we first see a "cute" graphic figure and then, looking more closely, see its sexual implications. Although the naked female figure has long been considered an appropriate subject for art, male genitals, especially in jewelry, are a radical departure. As a man making jewelry, Lewis feels that exploiting purely female forms might often be sexist, while utilizing his own body form would not. Tummy Tummy Tummy Tummy is a statement on social and sexual interaction using both male and female imagery. The figures function at two levels, as bodies with female breasts and male genitals and as faces. The breasts become eyes and the belly buttons suggest mouths. Two figures are attracted to each other but, embarrassed by this, their eyes roll up and they try to look elsewhere. In contrast, the two additional figures observe the others in a supercilious and judgmental way, exemplifying society's posture.

Memento Mori is Lewis's attempt to exorcise the grief he feels from his involvement with AIDS patients. With its carved bone skulls and stressed gold and silver forms, it presents a harsh and morbid image—a monument to death. A somewhat lighter message is represented in Critter, a small but powerful creature conveying aggressiveness and fury within the context of fantasy. In a similar mode, Desolate Moon with Small Companions communicates melancholy sadness and loneliness. Even with companions all around, the piece suggests we are still alone. It holds a secret surprise for the wearer in the additional companions hidden on the back, but even these are lonely—such is the human condition.

Eva Eisler

Helen Drutt Gallery, New York, NY

October 29-November 26, 1988

by Toni Lesser Wolf

Trained in Prague, Czechoslovakia, at the School of Graphic Design and the School of Building Technology and Architecture, Eisler has consistently explored structural concerns in jewelry through the use of metal, organic materials and space. In the past four years, Eisler's work has evolved from constructions comprised of sterling silver, stainless steel, along with ivory, ebony and/or slate which displayed a clearly engineered feeling, to bridgelike assemblages (made from the same materials) that explored tension. The current exhibition begins at the source by illustrating Eisler's desire to approach design from its simplest origins (as regards shape) and to progress logically along an endless formal route.

The jewelry is divided into live basic categories: brooches and earrings forged from a single, angularly bent wire (the simplest solution to creating three-dimensional, spatial enclosures out of two-dimensional line); three-dimensional bridgelike structures; tension pieces out of silver and stainless steel; "T"- formations made from silver and slate and ebony "hieroglyphs" based upon the details of the "T"-formations.

Architecturally, Eisler uses space as an integral component of each design. Whether she is fabricating gridlike structures, like those of R. Buckminster Fuller, or two-dimensional cuneiforms with associations to ancient monuments, such as Stonehenge, Eisler succeeds admirably. Her jewelry draws the viewer into an alternative consciousness, another level of being. I believe Eva Eisler's "logical journey" to be most important, and I, for one, am riding along with her for the duration. Sculpting shapes out of ebony, curly-maple and purple-heart wood (which have replaced alabaster and soapstone in her jewelry), Suydam laminates these to lightweight, hollow silver forms. At first glance, this limited combination of materials seems stark and rather facile but, upon further examination, the materials prove themselves perfectly appropriate for Suydam's meticulously crafted, well-conceived forms. These bold, physical pieces—mainly brooches and earrings—echo both contemporary and ancient European jewelry. Suydam is inspired by "spiritually charged objects" like arches, emblems or arrows, which she then personalizes and abstracts, creating a quiet jewelry that is both traditional and contemporary.

"I see the body's potential as a landscape for sculpture," she says, "as an empty area on which to place three-dimensional objects which directly respond to their point of placement." And indeed, each piece relates to human anatomy while recalling its original inspiration.

For example, one brooch, Stonehenge, consists of two large angular and asymmetrical "U" shapes, the top "U" silver and the bottom purple-heart wood laminated together. Another is an elongated Urn made with a combination of mirror-finished, beveled silver that curves out into a crescent and angles down to a section of oxidized silver; polished to catch the light before it is laminated to an ebony tip. Also of silver and ebony, her large, magnificent Antelope Brooch, looks somewhat like a medieval crusader's banner. Finned Skeet, and Skeet Brooch, although their antecedent is the clay target used in trapshooting, carry allusions to Scandinavian ritual objects. Earrings take the shapes of Roman arches, flat fish and arrowheads. The one bracelet in the exhibit. Leaf Bracelet, is made entirely of silver and is a circle of ring-connected, overlapping leaves, which ingeniously popup when on the wrist.

Suydam's jewelry—balanced, strong and predictable—attains a stylistic refinement that does not compromise but contributes to the integrity of her art. And, because of her respect for the qualities that animate the shapes, a reverence surrounds her pieces that evokes their inner nature.

Information as Ornament

Rezac Gallery, Chicago, IL

July 8-September 14, 1988

by Lisa E. Bernfield

The theme of "Information as Ornament" was construed many different ways in this exhibit, which attempted to show how the bombardment of information contributes to society and how it influences the arts. Cindy Bernard's piece Security Envelope: IRS, at first glance a framed black-and-white pattern, offered very little information and stimulated only if the decoration was found to be pleasing. The pattern's role, in its original context, is to impede access to the information contained inside a business envelope. Her piece exemplified how symbols devoid of their context and removed from common usage become stripped of their meaning. With the daily bombardment of information, it is difficult to discriminate between the trivial and the profound. Content no longer adheres to its image.

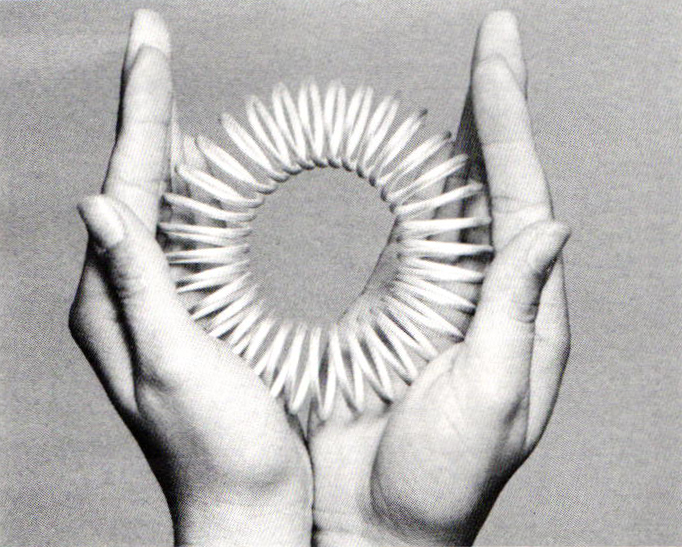

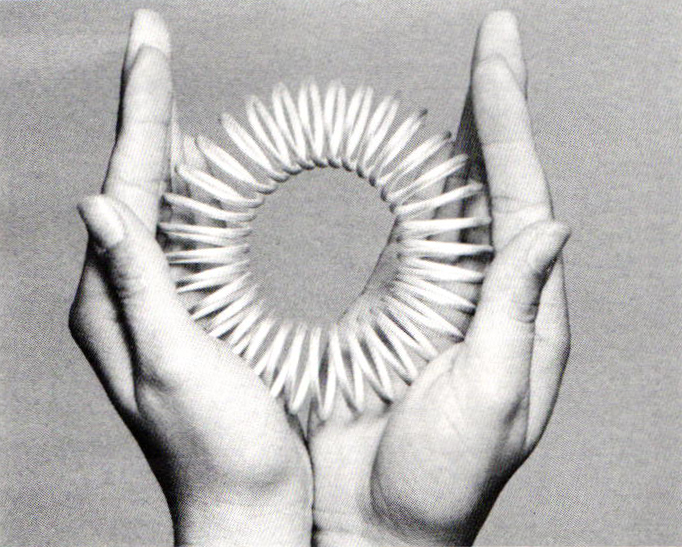

Gerd Rothman's Sammlung is a white-lacquered wooden box that contains 100 paper-thin castings taken from palm imprints of the artist's friends. They are filed in protective slide sheets with room for future "friends." The tin imprints belong to metalsmith greats, such as Hermann Junger, and their signatures are on the back of each palm impression. The palm castings, to those who were able to read the information, revealed each individual's pasts and futures in faintly engraved lines of love, life and death. Since the information could not easily be read, and since it was not apparent that these were palm imprints because of their disengaged context, what remained was a graphic pattern. One of jewelry's roles is to adorn the body, but here the process was reversed; a part of the body was transformed into an ornamental statement. Information became ornament.

The 13 common and recognizable symbols (the star, the Liberty Bell, the cross, the dollar sign and the swastika), painstakingly hand-cut out of steel, were the components of Otto Kunzli's Big American Neckpiece. The work is a trenchant commentary on the artist's recent experience of living in the United States, with its overload of information. He even stamped all of the symbols with "Made in the U.S.A." to drive home his intentions. Although, at first glance, Kunzli's "jewelry" appeared to be a traditional necklace, upon close examination one realized that it was not intended to be worn. The weight is too much for the body and chain to endure. The symbols weigh the wearer down, both physically and conceptually. They appear as one strange mass of indecipherable form, a dense conglomerate of social, political and historical references.

In Kevin Maginnis's Vaccination, a series of photographs show common people rolling up their sleeves to reveal their small pox vaccination scars. The scar symbolizes the belief in the power of science to heal, yet the work is not just informative, it can also be seen as a new approach to adornment. The scar, in this case, is the jewelry, just as Gijs Bakker's marring of the body with his "shadow and invisible jewelry" created a new format for embellishment (the imprint or indentation left by attaching a gold wire "bracelet" tightly around the arm).

Sheila Klein's Bobbypin looked like traditional jewelry, seeming to be decorative and wearable when viewed in a slide format, yet its scale and placement denied its place within the jewelry world. Her jewelry adorns rooms and architecture, not the body. Imagine a huge mood ring on a tower in Seattle.

This brings us to the last premise of this exhibition: to create a dialogue between fine and decorative arts. Richard Artschwager is a fine artist who uses the decorative arts as a source of inspiration, His piece Mirror consists of an inverted, finely detailed, grained-wood frame leading into a faded mint green plane of formica. Although there is no mirror there per se, one really felt as if the "image" glows due to the contrast of the dark wood-grained frame with the lightness of the green "image." This piece makes us believe this through its decorative signals and sensibility, not through actuality. Even though there is no image in the frame, from its ornamentation comes information.

"Information as Ornament" exhibited "craft" with "art" exemplifying that congruity of idea takes precedence over status. All of the work in the show whether jewelry, painting or sculpture, dealt with concepts. Although this might stir up hopes that a change had occurred, that an end to the tiresome art versus craft debates is at hand, this would be deceptive, for this type of exhibit is not unusual for the European artists/craftsmen/sculptors whose work dominated.

Sabine Mittermayer

Fire Works Gallery Halifax, Nova Scotia

September-October 1988

By Astrid Brunner

Sabine Mittermayer's 80-piece exhibit seems at first glance reticent and understated. Its dominant colors are low-key grey and god tones; its dominant forms the tube and the spiral. In order to appreciate the emotional strength of the work, it is necessary to overcome the separation of object and subject by wearing some of the rings, earrings, and bracelets. The interaction of human body shapes and created form is essential.

Mittermayer talks about the intentional simplicity of the work in this exhibit. She sees it as expressing various paradoxical but complementary aspects of her life as, at age 25, she has come to understand it. One of the paradoxes, for instance, is the fact that she has lived and worked in two cultures. Born in Munich and now living there again, she also came to Canada to finish high school and to learn English. She eventually became a student of Pamela Ritchie at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD), winning awards both before and after graduating with a BFA in 1986.

The silver and tombac, single rings, two-finger rings, earrings and bracelets reveal a fascination with the interact on of opposites and with minimal variations on a fundamentally simple theme: the male/female relationship. In some cases the tension is resolved partially in the work itself while in others resolution lies in the interaction of the human body with the object. The Silver Tubing Rings tend to need the body-object interaction in order to come into their own completely, while the tubing-plexiglass rings, for example, go some way to resolve the male/female paradox in the object itself. The formula on which these rings are built is that of a high-tech material (industrial silver tubing) being softened into femininity by another high-tech material (plexiglass).

Mittermayer talks with continental ease about the way she sees womanhood reflected in her work. Becoming a woman and growing in artistic maturity go together. Her interest does not lie in upstaging an opposite but in integrating it creatively. She achieves a balance between male and female, premeditation and intuition, and between the intellectual overdrive of her native Germany and the emotional "lotusland" inspired by the stark beauty of Canada's Nova Scotia. The attempted resolutions show a remarkable maturity.

Young Americans 1988

American Craft Museum, New York

September 15-October 28, 1988

by Michael Dunas

The "Young Americans" exhibition, a somewhat regular event since its inception in 1950 at America House in New York, has become over the years synonymous with the American Craft Museum. It has, in a loose analogy, become for the craft community what the Whitney Biennial is to the fine art world. Through a process of jurying 98 works out of 817 submissions, the 1988 competition, like its predecessors strives for a cogent, if not sometimes contrived, portrayal of a new generation (under 30) of American craftsmen, acting as it does as a measure of emerging talent and a gauge for the cutting edge of shifting styles.

This year's show, unlike most that I can recall, paints a modish portrait of the new generation—one that reveals influence of the new wave in decorative arts. The egalitarian nature of the crafts community has always been tolerant of borrowings from other art disciplines, and the American Craft Museum/Council has in the past attempted to forge amalgams through hybrid terminology like designer-craftsman, folk-craftsman, production-craftsman and artist-craftsman. So, it is not unexpected that the deco-craftsman would someday have his/her turn in the limelight, and this show seems to indicate that the time is at hand.

But there is a problem with the deco-craftsman, as there is with other schizophrenic labels. It is not clear whether the new generation wants their work to be considered decorative or just decorated; whether their objects are meant to complement an interior style or fashion of dress; or whether their objects are embellished with motifs that are meant to complement the personality of the object itself. This is not a new issue. Craftsmen regularly have tried to point out the difference between the painted pot or the ornamental brooch and a craft object that acts as a decorative accessory or appointment, just as painters have addressed the patterned surface in an effort to make the distinction clear. The danger of this ambiguity lies in the potential for exploitative publicity, for individual objects to be assessed only by their conformity to an all-consuming esthetic costume with which to adorn a public image.

By and large, the works in the show appear to be "decorated" predominantly by surface patterning, compositional pastiche and theatricality. Most of the metalsmiths and jewelers in the show: Catherine Butler, Claire Dinsmore, Sandra Enterline, Mary Hughes, Robert Laible, Christina De Paul, Laura Malecki, Tony Papp, David Peterson, Claire Sanford, Sandra Sherman, Alissa Warshaw have shared of these characteristics, often utilizing anodized aluminum, titanium, bronze and copper patinas that have become the surface techniques emblematic of the 1980s.

However, a shadow hangs over the show one that seems to inhibit the free play and experimentation of the traditional decorated craft object. There appears to be a certain control exerted by the craftsman to conform to an overall look associated with the post modern style, particularly Memphis, that has arrived on the scene to rejuvenate the decorative arts. Beneath the histrionics of many of these pieces, there is a sentimental appropriation at work characteristic of the new decorative arts. Sometimes it is the neoclassic; other times it is Pop or Art Deco that takes over as a facile signifier of the past, luring us through familiarity. What is egregious about this "decorative arts" approach is the lack of depth in the work — the image is all there is; the experimentation with decorated forms becomes merely a saccharine exercise of packaging the viewer's response.

Possibly it was the Museum's attempts at packaging that caused only those craftsmen who fit its vision to submit slides; possibly the choice of jurors was too restrictive esthetically; or possibly this is truly the undercurrent of the young generation, and the 800 entrants (down from 11,000 in the late 70s) provided a mandate for this move toward a decorative sensibility.

Ironically, the three award winners—one each in fiber, glass and metal (Lisa Norton in metal)—went against the grain of the show's noticeable homogeneity. Their work was decidedly abstract, conceptual, minimal, sacrificing surface in the service of form, inconsistent with the prevailing post-modernist style. Maybe the jurors wanted to award these craftsmen as a relief from the tedious conformity of the pack, or, maybe, as their statement indicated, they did it to convey their suspicion that the diversity of work they knew was being done around the country was not represented by the submissions. In any case, while "Young Americans" is not the be all and end all of the avant-garde in crafts—the selection process alone is flawed enough to give us pause—it remains a dependable showcase, raising questions about direction and identity that are an insistent part of any discussion about crafts.

New Dutch Visions in Wearable Sculpture

Joanne Rapp Gallery, The Hand and the Spirit, Scottsdale, AZ

December 1-31, 1988

by Lynn R. Rigberg

As the show's title suggests, this assemblage of contemporary jewelry has a double theme. The exhibit has both crossed the Atlantic from The Netherlands and traversed an esthetic isthmus that separates jewelry conceived as art from art conceived as jewelry. Collectively, these works reinvest jewelry with its original meanings, including personalization and risktaking as well as adornment. Charon Kransen, curator of the show reflects that the designs signal a reaction to traditional Dutch strictures, emanating from a culture where the concentrated population of 15 million must regiment life.

In their first reactionary step in the 1960s, the Dutch designers began to use nontraditional materials like aluminum, rubber and brass, meanwhile keeping to elementary techniques and "minimal usage for maximum effect." Today the movement maintains both its discipline of design and its challenge to the precept that the highest inherent value in jewelry is in the value of the materials over art, philosophy and individuation. The show includes collars of anodized aluminum or wood; bracelets of cleverly connected laminated foil candy wrapper squares; painted wooden shapes that attach and adorn uniquely; plus pieces created of rubberbands, corroded tin, plexiglass, cork and fabric-sheathed steel. There is silver and gold, but in unembarrassed apposition with less costly copper and tin.

What these and the other pieces have in common is their combination of qualities of freedom from traditional constraints and sound discipline of accomplished craft. The unifying idea behind them is to stretch established limits rather than to revolt against esthetics and form. Many of the designers represented in the show have come from other areas of design to jewelry. Kransen attests that, in Holland, "people are coming now from other places to think about the human body, and about jewelry and its meaning."

An altered sense of self in space results from wearing the thin, bent, oversized, dimensional necklaces of cotton-wrapped steel by Lia De Sain, Rian De Jong's wooden shoulder-stands also break through traditional perceptions of adornment, redefining the human form and the architectonics relating to it. There is romance in the delicate three-dimensional necklaces of spirals elaborated in tin, gold or silver and looped together in arabesques by Coen Mulder, Humor underlies paper bracelets and necklaces by Beppe Kessler. Their synergistic charm is enhanced by the materials used (Playboy and The Financial Times).

The process in the works extends to the wearer, but the pieces also can be appreciated on display. Richard Walraven's corroded tin designs, developed in typically methodical Dutch fashion out of flat circles, are segmented and folded back to create strong, monumental pieces wherever they rest or hang. Charon Kransen's graceful pins and hair accessories combine paint, canvas and metal and can be set out in three-dimensional exhibit. Overall, the Dutch jewelry demonstrates how the line between form and function can blur, with art emerging as the prevailing connotation.

This exhibit will travel to J. Cotter Gallery, Vail, CO (Jan. 1989); Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, WA (Feb. 1989); Anne Reed Gallery, Ketchum, ID (Mar. 1989): Concepts Gallery, Carmel, CA (April 1989).

Jan Craft

Gaston County Museum of Art and History, Dallas NC

October 1-December 31, 1988

by Jane Kessler

Jan Craft has pared her visual vocabulary down to a triumvirate of powerful elements; the circle, the triangle and a single axial line. The circle alone assures a certain depth and stability in the work for, as Carl Jung noted, the circle is the most powerful cross-cultural archetypal symbol; one which represents wholeness, completeness, source and end. For Craft, it provides a base to work from. "Its simplicity lends itself to be used freely without being intrusive on other images contained within. The circle," says Craft, "is symbolic of nature because of her constant cycles and processes."

Craft often pairs the circle with an equilateral triangle, a shape also symbolic of stability and power. It functioned as the compositional superstructure in Renaissance paintings and often represents the spiritual trinity. The single axial line frequently serves as horizon line, strengthening Craft's reference to nature and landscape. It is the critical element in creating the delicate and asymmetrical compositional balance that is a hallmark of her work. With this simple vocabulary, Craft describes for us the limitless variation that may be found within a self-imposed and finite limitation.

The 20 pieces in this exhibition, ranging from earrings to human-scale sculpture, share with one another a manifest sense of assuredness, a near complacency that derives from Craft's adherence to such a stable compositional bent. What appears limitless, however is Jan Craft's technical skill and an imagination that is set loose in materials and technique rather than in composition. There is grand variety in the surfaces, textures and materials that she applies to the solid and unvarying shapes.

Craft attributes her technical know-how to her instruction at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, under the skilled guidance of such masters as Brent Kington, Richard Mawdsley and Darryl Meier. The metals department at S.I.U. is renowned internationally for instruction in the formation and use of Japanese alloys and Damascus (pattern-welded) steel. Kuromido (copper and arsenic), Shakudo (copper and 24k gold) and Shibuichi (copper and silver) are Japanese alloys that Craft uses in combination with other metals in many of the pieces in this exhibition. She also employs Damascus steel in her work, adding yet another strong visual design element.

Among the most successful pieces in the show are two brooches, Landscape Series #5 and Magnificent Perfection, which use Damascus steel to suggest earth, sky or water. Gold in 14k, 18k and 24k is used as bright contrast to the patterned steel. Though many of the pieces in the exhibition are wearable, the functional elements are aptly disguised and function is clearly subjugated to form. Small sculptures, such as the pieces in the Arch Series are comparable in scale to jewelry but eschew function altogether. The arch, a form that derives from both circle and triangle, becomes a freestanding playground for Craft's technical skills.

Two larger pieces in the exhibition Bondoukou Disc and Arch #6 are simply small pieces magnified. Few changes occur either in feeling or in compositional relationships. These works, though larger and perhaps more powerful due to their increased size, are still as delicate and meticulously crafted as their smaller counterparts.

Jan Craft presents a body of work that is both cohesive and varied. It is clean, confidently resolved, elegant and simple.

CREDITS:

Jane Kessler is a freelance curator and writer and founder of Curators Forum in Charlotte, NC.

Jan Loyd is an arts administrator living in Newell, NC.

Lisa Bernfield is a jeweler living in Chicago.

Roberta Floden is a writer living in San Anselmo, CA.

Astrid Brunner is an artist and writer living in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Michael Dunas is a writer in the fields of craft and design and lecturer at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

Betty Helen Longhi is a metalsmith living in Seaford, DE.

Toni Lesser Wolf is a jewelry historian, lecturer, curator and writer living in New York City.

Lynn Rigberg writes on the arts from Phoenix, AZ.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Mary V. Smith – Burning Brightly

Cultural Myths Defining Jewelry

Metalsmith ’83 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

The Work of John Marshall

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.