Metalsmith ’90 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

24 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1990 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Elizabeth Chenoweth Palmer, Donald Friedlich, Rodney McCormick, Ken Bova, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elizabeth Chenoweth Palmer

Artworks Gallery, Seattle, WA

February 17 - March 31, 1990

by Keith A. Lewis

Elizabeth Palmer has for years been translating the strange, honest logic of children's drawings into metal. The making of these pieces, and her familiarity with the disconcerting directness of children, has shaped her vocabulary of form and content. The work in this show is about three things; the harm that we do (physical, psychic, spiritual) to one another, the burden of pain and alienation that we carry about with us after receiving (or causing) such harm and the flight of the spirit that allows us to discard those burdens, keeping only the vision and strength that the pain has given us. For Palmer the abuse of children is both a horrible reality and the unavoidable metaphor for the cruelties and injuries of the adult world. Several pieces in the show, ostensibly about child abuse, achieve a depth of feeling and emotional commitment rarely achieved (or attempted) in metal. The pieces evoke, in some mysterious way, both the event of child molestation and the fabric of menace that surrounds an abused person, child or adult.

No Daddy serves as one of the thematic and emotional poles of the show. A small figure, with huge head and red bead eye cries a long stream of tears. From his/her shoulders sprout tiny vestigial golden wings - evocative of the limbs of a thalidomide child. Below the body dangles a pair of twisted fragile wren's legs. The lace is turned up towards a looming, cloudlike form, from which emerges a hand holding a penis. Stamped deeply, three times, across the child's face and body is "No Daddy." The aura of abuse and exploitation is palpable, and the piece rivets the viewer's eye, forcing a confrontation with usually ignored pain. This piece, which was once characterized as "too disturbing" by a gallery owner, has prompted tears and sincere thanks in some, discomfort and a sense of inappropriateness in others. The wearing of this piece entails deep emotional commitment and the wearer would truly have to share Palmer's vision and be willing to take it out into the world.

From these pieces about hurt, Palmer moves into pieces that center around the memory of pain and the legacy of abuse. David and I Remember grew from Palmer's friendship with David Duhaime, who is serving a life sentence without parole for the murder of a young woman 11 years ago. Palmer believes that Victoria, the woman killed, has become enmeshed in David's waking and sleeping life. Hence the duality represented in David and I Remember: the Janus-like features, the shreds of two hearts tangled together, the dangling limbs tied to the heart, the stream of justification or explanation or remorse emanating from the figure's mouth.

Victoria's death, tragic and senseless, has been the catalyst through which David, himself a victim of childhood abuse, has remade himself. His drive to learn and grow - to transcend his actions despite his certain lifelong imprisonment seems to Palmer to typify "the awe and wonderment of the human spirit." This is dangerous ground, but Palmer never asks for pity, she only suggests that flowers can grow in the most unpromising soil. Other pieces also address confinement and dreaming, freedom and attainment. Despite her use of occasionally pat imagery - the broken heart, the bars of a cage - Palmer evokes scenes of resilience and bravery.

At the other pole of the show is Blessings of the Earth on the Sow, which was inspired by a Galway Kinnel poem that reads, in part, "The bud stands For all things…for everything flowers, from within, of sell-blessing." A lumpish and utilitarian sow somehow transforms herself before us, as her skin is stripped back to reveal a brilliant pink-and-lemon interior. From an often-shattered but still shining heart, highlighted by a pointing editorial finger, rises a delicate dried rosebud. Exuberant stars swirl about, echoing and joining the jaunty curl of tail. Human figures suckle from bright magenta teats and below it all hangs a placard telling us that, "sometimes it is necessary to remind a thing of its beauty."

This apotheosis, this reminder of self-worth and loveliness - despite memories of derision and abuse - is the essence of Palmer's work. It's a sweet essence, especially in our metalsmith's world safe (and salable) design. In that world, those who imagine themselves audacious embrace the newest technique, thus adding to a toolbox that is used to do…what? Used to say…what? That makes us feel…what? None of this will satisfy Palmer; quietly and with serene integrity, she is showing what demands can be made of herself, of metal and of the wearers of jewelry.

Keith A. Lewis is a metalsmith chemist and gay/AIDS activist living in Kent, OH.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hola Barcelona!

Galerie Jocelyne Gobeil, Montreal, Canada

March 3 - April 7, 1990

by Luc Pilon

Highlighting the most recent movements in contemporary jewelry from Barcelona, this group exhibition was both provoking and fascinating. All of the work has a very clear or loose approach that carries with it a free spirit of creativity. This characteristic spirit results from a balance between the rational or controlled approach to making and the powerful intuitive feeling of conception in each artist's work. The sculptural quality was evident in the scale of the works, which function both as wearable jewelry and as objects independent from the body. This quality is also apparent through approach to material, orchestrated to expose creative means rather than material value. It was delightful to note the total absence of both gold and stones.

Barcelona discerns itself as the only center for contemporary art jewelry in Spain and is home to the Escola Massana, where Ramon Puig Cuyas heads the department of jewelry. All of the artists in this show at one time either taught or studied at this school. The resultant small community of jewelers nevertheless manages to keep a distinct individuality among its members. Seven of the Catalan artists were included in this show: Ramon Puig Cuyas (also the subject of a solo show at the Helen Drutt Gallery in New York this past spring), Xavier Domenech, Carme Roher, Virginia Bekla, Paul David McClure, Anna Font and Marta Breis. These jewelers form a part of a new avant-garde movement that continues to question, search and redefine the nature of jewelry.

Puig Cuyas navigates us through images of the sea (fish, waves, mermaids) to create his own mythical world. We recognize his irony, poetic and sensual intentions while he fabricates a story in impeccable collage form. With the application of primary colors, he brings us towards a warm climate at the edge of the sea. As The Swimmer with the Sun demonstrates, his work embodies the enchanting characteristics of the Mediterranean artist.

More than serving a single decorative function, Domenech's architecturally inspired works are wearable minisculptures. It seems as though issues of decay and pollution are raised as we recognize images of scaffolding in silver around rusted iron forms. Adorning the human body, they are structures that form a dependency with the figure. He creates a balanced whole between simplicity and industrialism.

Also taking architecture as a departure in her self-expression, Roher presented both sculpture and jewelry. Ancient monuments, amphitheaters and ruins seem to be the source of her inspiration in pieces that although relating spatially to the body are not wearable. There is a sense of the past in her patinated, crudely finished surfaces, like abandoned places or discarded objects.

Beida's paintings on laminated cardboard offer a three-dimensional portrait of a unique Spanish experience. The bracelet A Por el Toro depicts a scene of a Spanish bullfight like an expressive painting. Spontaneity in its rawest form is evident in a neckpiece called Reunion de Amigos, a plastic box containing a cardboard painting and a moth ball hung by a steel cable. Her work and her process were the most intuitive and spontaneous of this group.

The sentiment to be "playfully dangerous" of McClure, a Canadian who studied and worked in Barcelona, draws the admirer as a toy attracts a child; there is the desire to touch and explore. However, underlying this, one discovers a second skin. One sees images of glass shattering, spikes piercing and a saw cutting. There is a juxtaposition of innocence and reality, each fighting for equal value.

Seemingly influenced by the primitive art of aboriginal or African tribes, the work of Font resembles idols or statuettes. Two pieces in particular, Home (Man) and Done (Woman) use bold shapes, unlike the constructed approach of multiple elements inherent to much other work in this exhibition. There is an unrefined spontaneity in her sentiment, yet, coupled with impeccable technique, her work has a powerful simplicity.

The assembled brooches of Breis have influences from both constructivism and oriental art. Using solid forms and fine lines interwoven with clear and opaque shapes, her work is a balance of fragility and boldness. She invites wearer participation through changing the form and the manner in which the piece is worn.

Luc Pilon is a Montreal jeweler, who studied at The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Donald Friedlich

Garth Clark Gallery, New York

April 10 - May 5, 1990

by Nancy Boxenbaum

In Donald Friedlich's exhibition, visual simplicity and elegance belie an undercurrent of intellectual complexity. The works are divided into two series, Pattern and Erosion, and, with the exception of two bracelets, are all brooches. Created from stone or glass, each piece exemplifies Friedlich's sensitive appreciation for and deft manipulation of material. Several brooches (most are 1½ to 2″ square) contradict their natural properties by appearing to be synthetic: the glass brooches look like lucite; the onyx, rubber. This deception is underscored by the handheld weight of the brooches that actually appear light and delicate. The two agate bracelets do not partake of this strategy. They are large and forbidding, both visually and physically.

The surfaces are delicately carved with square grooves, linear ridges and cubes set in shallow relief against carved backgrounds. Though the edges are straight, carefully planned and formal, the surface undulates with an organic rhythm that counteracts the sense of rational design.

In this way, Friedlich establishes a dialogue within each series. The surfaces in the Pattern series, for instance, are neatly carved grids, with one displaced element set in relief. It is a play on the notion of patternmaking, especially the characteristic of regularity, since major emphasis is placed on either the wavy, organic shape of the surface or the displaced element that interrupts the pattern.

In the Erosion series, each piece has a local element that is raised and highly polished. What has "eroded" from the background of the work has a matte finish, contributing to an implicit irony that is the theme of this series. The high-tech, post-industrial esthetic of highly polished areas evokes the intervention of the artist's hand and his control over his materials, yet his ultimate dominance is questioned by the organic shape of the surface and the allusion to nature, over which humans have no control.

Each piece is self-contained, physically proportioned to scale. However, because the surface pattern extends to the edges of each brooch, it might be perceived as a fragment of a larger, infinitely repeating pattern. One rectangular brooch of red jasper has horizontal bands of gold inserted into carved grooves, evoking a "ladder" scheme, while others with grid patterns look like details from an aerial view of a cityscape.

Nancy Boxenbaum is the editorial assistant at the College Art Association, New York.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rodney McCormick Lamps, Sculpture, Lighted Sculpture

Owen Patrick Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

June, 1990

by Michael Dunas

In what can be considered a debut exhibition, Rod McCormick has jettisoned his previous connection with limited-production jewelry for a startling range of engineered sculptures of welded steel rod and perforated sheet metal. Following the example of his Fellow metalsmiths who made the 1986 "Form Beyond Function" exhibition a salvo for change, McCormick here further testifies to a gratifying expansion of "metalsmith" sculpture from a principled base of jewelry and holloware esthetics. His strategies with volume, compositional logic and precise construction enhance the veiled wit of his adventurous forms.

Three floor pieces, torcheres, which adhere to the strict notion of lamps as light-transmitting fixtures, are slyly irreverent to the customary pose of upright beacons, passive onlookers in a room's interior decor. The paper-covered shades of two lamps in particular project a delicate, ethereal light in the familiar Japanese lantern idiom. The fixture, on the other hand, is a composite of McCormick's recurring motifs, the industrial shapes of ducts, funnels, chimneys, elbow joints, grating and sheathing that is the vocabulary of the sheet metal worker. Taking its cue From the masklike expression of the lantern, the staunch plumbing assumes the posture of a naive tinman, radiating gleefully, armatures akimbo, lamp head straining with interest to engage the conversational space of the room.

The metal surface of most of the work in the show is treated with acid, producing at times a blackened and at times a rustlike patina. The slapdash application appears as a mottled glaze rather than the result of age and weathering. It is a telltale sign of McCormick's ironic attachment to prosaic metal, appreciative of the abstract qualities of color, form and texture without romanticizing them. He finds fantasy in the realistic applications of metal without delusion of recondite preciousness.

In contrast, the tabletop sculptures and their related wall reliefs are one step removed from his lamps and illuminated tableaux, transitional pieces that mark the shift from jewelry. In scale, they describe a torso with the implication of theatrical adornment, and as such they isolate more clearly McCormick's evolution from the semantics of constructivist jewelry: the abstraction of geometric motifs, the emphasis of volume over mass, the caged anthropomorphism, the delicate welding, the transparency of structure and, above all, a rationality of design that is physically alien yet cerebrally enticing.

As a result, they lay a foundation for appreciating the radical achievement of the two illuminated tableaux. Bird-cage in size, they are enclosed steel-mesh containers with a suspended quartz halogen lamp that casts a glow on an assembly of austere perforated vessels at the base of the cage. The primary subject of the composition is light, contained within the piece rather than transmitted out into the room, closely resembling the inner luminosity of a thick glass form. Tension is created in our feeling that more exists than we actually know, that there is more light than matter, that material forms result less from the reality of Fabrication than the illusion of light's refraction. The effect is surreal, with the holloware a mirage, dematerializing into what McCormick calls ghost forms of itself.

The purity of the abstraction derives from his evocation of material anonymity and structural logic, concepts germane to minimalist ornament as well as independent sculpture. The vessels are reductive and nondescript. The cages look like conical lampshades stretched and pulled down to the base. Even the fixture that holds the lamp reflects the overall design of a simplified rotational geometry. Efficient, ordered, calculated, they nonetheless uphold McCormick's trenchant wit directed towards metal's debased industrial past.

Michael Dunas writes on art, craft and design and teaches a craft history course at University of the Arts and Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

New Ohio Jewelry

Massillon Museum, Massillon, OH

January 28 - March 4, 1990

by Matthew Hollern

The importance of the show was perhaps not the "new-ness" nor the "Ohio-ness" of the work, but rather its ability to reach a lay audience. Costume, fashion and fine jewelry were defined in curator Bruce Metcalf's statements, drawing on the broad scope of studio jewelry. Under this umbrella, then, the plastics, found objects, small sculpture, chain mail and architectonic forms in the show could be understood as compatible "vehicles for self-expression and the exploration of ideas." The purpose of the show was simple: to exhibit the diverse, innovative works presently being done in Ohio, to pave the way for greater public interest and understanding of jewelry.

Work by Robin Kraft made thoughtful use of enamels, electroforms and mixed media. Her series of 10 brooches explored wood, paint, nails, thread and gold leaf, through ghostlike, figurative images. Her work varies from emphasis on form and volume with subtle enamel coloration, to flat and highly graphic pieces. The work came across as formal rather than conceptual or thematic.

Jewelry by Kathy Buszkiewicz had a simple Eastern quality that emphasizes smooth, pure forms with minimal surface embellishments and pattern. She describes her work as "wearable sculpture," addressing the body as a "mobile environment." Yet, concern for wearability was evident. Surreptitious Snare effectively created tension between beauty and danger, like that of a Venus-Fly-Trap. A web of tiny interlaced fingers bridge the mouth of the brooch. The unified surface of fine silver, lightly crosshatched with file, cuts has a plant-like quality that sharply contrasts with the toothy orifice.

Ilana Painter, a graduate student at Kent State University, exhibited a series of jewelry in chain-mail. Her work went beyond the basic labor of making mail to create innovative forms of drapery. She exploited the fabriclike qualities of the material in rolled and folded neckpieces. She further departed from traditional mail in her use of patinas, bone and rubber O-rings. Though seen as adornment, the drapery maintained the essence of mail, conveying a Protective armorlike quality. The work succeeded in balancing the use of a familiar reference with new colors, forms and contexts.

Work by Kira Louscher included a very large, burdensome neckpiece. It is perhaps, the work furthest from the mainstream, maintaining its jewelry reference through the use of "current design trends." The neckpiece or sash is a personal composition, familiar yet fresh. She combines gilded wood forms, raw wire cages holding objects and small, shallow pierced vessels patinated green. Her discussion of physical metaphors for love and hate, male and female, is evident in her larger works. The raw quality of her work is effective but for the mechanisms where the question of function and wearability arises.

Jewelry by Cindy Cetlin, Susan Ewing, Anna Nuzzo, Jonathan Quick and Roberta Williamson was also included in this exhibition.

Matthew Hollern teaches metalsmithing at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ken Bova

Artifacts Gallery, Bozeman, MT

April 20 - May 16, 1990

by Harvey Hamburgh

They could be eloquent totems of mysterious cults: the Clan of the Bluebird, the Clan of the Hand, of the Dream Man, of the Brook Trout. We can imagine these clans as constituting a diminutive tribe, with a sympathy for the smallest things, delighting in the discovery of minute, colorful bits of a potent world, and taking pleasure in decorating themselves with these treasures that others would disdain, or never see.

The wearers of these ornaments possess a low order of technology, but a compensatory sophistication of stylistic invention and responsiveness to the magic of the visual. Their spiritual life seems to be focused upon the celebration of rich detail; yet these clans lade into Fantasy with the discovery that the evocative totems are products of the artistry of Ken Bova, a metalsmith living and working in Bozeman, Montana.

Bova has, for some time, explored a jewelry of abstract shapes cut from sterling silver, surfaced with rag paper, paint and varnish, with found objects and precious stones tied to the flat fields of color. The new work continues in this mode, configured in familiar silhouettes. The fabrication is simple and direct, and, in its avoidance of forging or casting techniques, free of any suggestion of industrial production. These pins, more graphic than sculptural, are thin and delicate, and though substantial for utility, they demand a care of handling appropriate for the precious and ephemeral.

Commonly valued stones and metals are employed in conjunction with unexpectedly prized materials, such as a cross-section of bone, a metal button, a flash of wrapping paper, a rupee note from Nepal, a tiny, sinuous twig, a piece of pencil, a fragment of a house key, the wing of a butterfly. These objects surprise us in their beauty and draw us into a curiously integrated world. Though each element remains discrete, they interact upon a vibrant, variegated plane, mutually reinforcing their preciousness.

Bova's unique sensibility is shaped by several distinct experiences. The prominent usage of silver wires and varnished papers in his constructions stems from his childhood play amid the ribbons and jars of sparkling glitters in the back of his parents' flower shop in Texas, while his particular vision of ornament, as a surface to be aroused by color, shows signs of his early training as a painter. The surfaces are emphatically patterned, whether with brushstrokes or flecks of goldleaf, providing a light accompaniment to the rhythmic placement of the tied corals, crystals and bones. Bova's love of pattern derives from another passion, Montana fly fishing, and a consequent close-up study of the surfaces of trout: the tactility, sheen and variation of the scales, as well as the patterns that could be extrapolated from tropical fish.

Bova's cold-connection technique also relates to the skills and satisfactions of the fly-tying process. The silver pin-stems of his pieces culminate in spinning spirals that ignite the dynamic relationships across the face of the pin. The spiral stem of No Stranger with its benign, Buddha-like profile acts as a symbol of the psyche, as if it were diagram of this charismatic character's consciousness. The spiral in Green Piece might suggest the eddies of a whirlpool, as the applications of pearl and coral, the serpentine of gold, the foamlike dashes of paint and the brilliant colors of sand, sky and sea all create the ambience of a palm-size tropical paradise.

The image of the hand, traced From the artist's own, and appearing often in Bova's oeuvre, can also symbolize the power of the artist to synthesize and shape reality, and to beckon us into an intimate, luminous realm that reveals the special, modest beauty of small wonders.

Harvey Hamburgh teaches at the School of Art, Montana State University.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contemporary Jewelry

The Baker Gallery, Kansas City, KS

September 15 - October 15, 1989

by Ann E. Erbacher

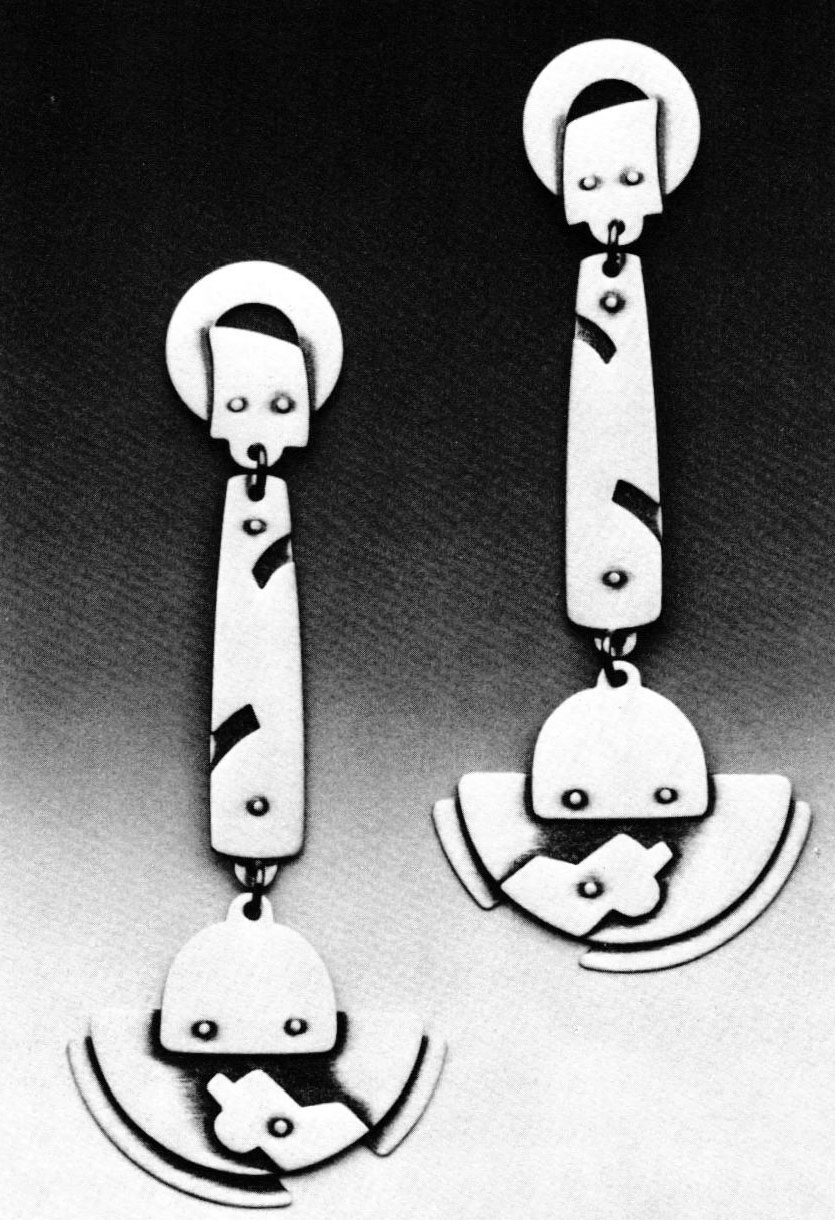

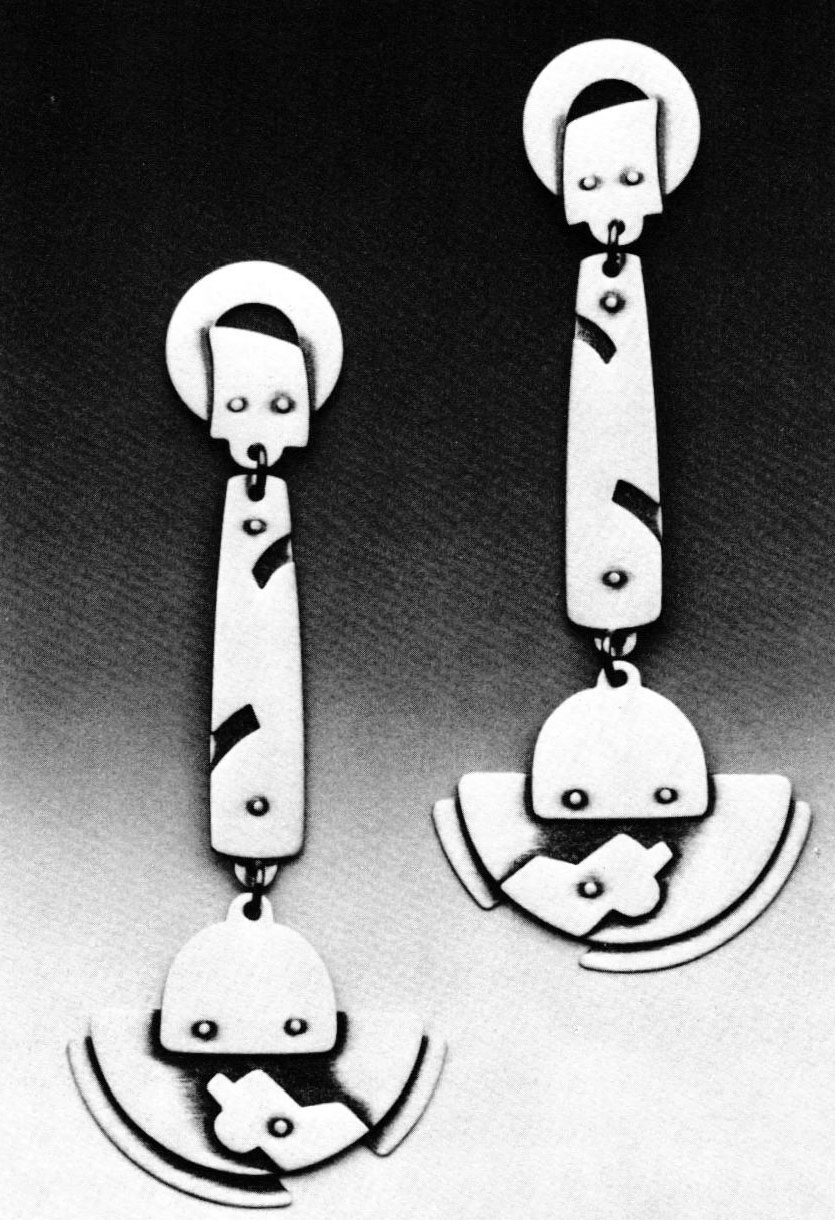

The Baker Gallery hosted an exhibition of nine Kansas City-based metalsmiths, most of whom trained at The University of Kansas in Lawrence. The work of husband and wife team Bill Ruth and Susan Mahlstedt revealed a strong sense of whimsy. Their pins, earrings and one necklace employed a variety of motifs, from architectural elements to arrows, cars, cows, fish, keyholes, ladders and palm trees. The pieces are constructed primarily of satin-finished sterling silver and acrylic, with some airbrushed enamel paint, 14k gold, onyx and lapis. Riveting and piercing are two construction techniques frequently used. Elements hang freely from the main body of the pieces, adding a sense of movement when worn.

Jewelry by Robyn Nichols is wearable sculpture strongly influenced by nature forms. Highly polished sterling, chased and repousséd, is used with coral and pearls. The titles, Berries, Chinese Lantern, Eucalyptus and Kelp, signal their design sources.

Debbi Sprinkle's jewelry relies on abstract forms, creating tension through the use of various shapes, colors and textures. Sterling, copper and brass are used, sometimes with agate, in earrings, pins and bolo ties. Earcuffs are Sprinkle's trademark item. The Doorway Bolo combines copper and sterling in a simple yet effective design reminiscent of Santa Fe architecture.

The triangular forms of Keith Harryman's pieces are reminiscent of sails and windsurfing. Sterling, white gold, lapis, onyx and opals are used in the earrings, pins and one bracelet which combines highly polished and textured surfaces accented with stones.

Philip Voetsch uses mostly 14k gold and vermeil in his limited production, fashion jewelry. The forms are primarily domed circles and teardrop shapes with pierced "windows" to allow the highly polished surfaces of the backings to contrast against the satin finished top pieces. A triangular pin with three spherical elements was among the more interesting of his pieces.

Karin Jordan's jewelry employs sterling, nickel, mokume, freshwater pearls, ebony and ivory in combinations of geometric and organic elements. She ascribes her influences to Art Deco, Japanese, and Southwestern design, although the Japanese influence is most apparent.

Genevieve Flynn's rings, earrings, pins and bracelets employ mostly sterling, with some use of ebony and aluminum. Piercing is used to add interest to the shapes. A circular sterling element is contrasted with a magenta aluminum, triangular piece in one pair of earrings.

Michael Wyckoff uses primarily gold and faceted precious and semi-precious stones in his rings, earrings, pins and one necklace, although ebony and pearls are also employed. His work had the most commercial appearance of that exhibited.

Ann E. Erbacher is the Registrar at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Harold O'Connor The Intuitive Spirit

Hughes Fine Arts Center Gallery, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND

February 5 - 23, 1990

by Nancy Soonpaa

Harold O'Connor's use of spare, clean lines and sharply delineated shapes evokes images of New Mexico, where he works. The sandlike roughness of his textured surface is set off by the sharp glint of a burnished shine. The shapes - unpolished pebbles and randomly stacked tubes - bring to mind a mysterious pile of tumbled rock, or perhaps the rough truth of a sunbleached stack of bones. His work is also drawn from experiences with nearby Colorado's mining industry. In a nod to technology, O'Connor uses eyelets and twisted wire to give an ordered, structural quality to the compositions, lending a sense of tension/compression to his subtle reflections on life and nature.

One group of O'Connor's pins employs lengths of rough, usually silver, tubing arranged in a pick-up-stick style, although in one case they form a tightly constructed, boxlid configuration. Eyelets bearing lengths of twisted wire run from tube to opposing tube, capturing in their relentless midst a slender cylinder of gray-veined soapstone, or a crystal-line length of bluish-green tourmaline girded by fine gold. Several of these pins are favored by a covering of metal, hammered, textured and shaped to drape as gracefully as fine silk. To set off the drapery's flow, O'Connor adds a common pebble, worn to a naturalistic taupe by the passage of time and grooved to receive its restraining wires of shiny gold. Each of four wall plaques (parting Stream, Island in the Sea, Fields Within, and Pathway to Sargus) contains a tiny pictorial collage of 18k gold, silver and copper, displayed in a wood frame. Within, an inverted stack of raised suede mats, in a tonal progression of desert beiges, leads the eye to the art work itself.

All four of the framed statements begin with a square border of flat wire set on edge, layered on top of and beside irregular, textured slips of other metals. In one piece, the square has been broken, the upper right quadrant floating lazily away from the lower half to evoke a Parting Stream. In another way, the inner square is firmly centered on a larger flat square, as if to contrive the Field Within.

Nature is a major theme in O'Connor's art. One ring beautifully combines the natural element with the man-crafted, to form a harmonious yet dichotomous whole. The ring begins with a chunk of silver, irregular as the day it was plucked from the earth. A tapering shank of 18k gold attaches at one side of the back and, swelling, approaches the other, where it penetrates to the front of the ring through a propitiously placed opening in the silver. The end of the shank, smothered in shiny, regular, fine-gold granulation, stands in mute contrast to the bumpy silver beneath.

There are occasional flaws in O'Connor's work, in both esthetics and craftsmanship. A rough cigar shape, appearing in both pins and necklace, jars an appreciative reverie. Whether this shape sports a bear claw (the necklace) or is set off with a stone (the pins), it bears an unpleasant and uncanny resemblance to an alien invader, sufficiently spoiling the mood. The tension/compression pieces are also marred, at times, by the obvious presence of glue peeping beneath the captured stone; this concession to security betrays the artist's intention, as does the disconcerting aspect of some wires, which appear to have relaxed enough that the captured stone could escape, if it had a mind to.

Nancy Soonpaa is an attorney, lecturer in English, and a student of metalsmithing at the University of North Dakota, Grand Forks.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Metalsmith ’87 Winter: International Exhibitions

Komelia Hongja Okim Exhibition

Ryan Roberts’ First CAD Design

Metalsmith 1996 Exhibition

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.