Metalsmith ’90 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

22 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1990 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Pamela Lins, Randy Long, Cara Croninger, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Pamela Lins: A Kept Object

BACA Downtown, Brooklyn, NY

October 20 - November 18, 1989

by Lisa Reden

The show is comprised of five works, each consisting of object groupings and/or vessels. In each work, the objects and vessels are contained within a certain prescribed space, displayed upon a platform or within a structure. The objects relate well to each other. The forms are varied and engaging, while the surfaces have been worked with obvious care and knowledge of patination.

Still Life is composed of seven vessels carefully arranged on a wooden platform. Lead, copper, gold, brass and steel have been used for vessels where the emphasis is on the warm colors and subtle textures, rather than a cold, reflective surface. Each vessel moves with a gentle rising and falling of the surface that breaks with its primary geometry. Romanticizing a given moment in the past, each piece is set as an idealized alchemist lab. Fluid spilled from the beakers and flasks has left its trace in stains on to the objects themselves but does not interact with its surroundings. These objects have a purely esthetic role and are kept at a distance from the viewer, in a desire to leave this idealized moment intact.

In another work, each of five found objects placed on a wooden ironing board has a single brass letter attached to it, spelling "Grope." The forms are full, rounded and familiar, yet out of context on the ironing board, they are difficult to place. Bicycle seat, pitcher and funnel are easily identified. On the left, however, the form might be a car headlight; on the right, possibly a cow bell. The surfaces of these objects are smooth, worn by time, with signs of rust and erosion. The impulse is to feel them, pick them up like irons off the ironing board.

Kept consists of four boxes of wood, glass, linen and steel which are mounted onto the wall. Each box has a single, crisp letter sandblasted into its glass surface, so that the four boxes form the word "kept." Each of the boxes contain a steel object, the first with the word "skeptic" raised from its surface.

I am reminded of Japanese esthetics - simplicity, irregularity, perishability and suggestion when viewing Lins's work. Simplicity comes through in the forms she achieves, their muted colors and arrangement. Irregularity is her delight in imperfections, which altogether make a rich surface. Bumps, scratches and rusted areas, in contrast with smooth worn sections, connote the perishability of things. Time erodes their physical presence, but these objects still suggest value and beauty in their need to be kept and appreciated.

Lisa Reden is a jewelry designer and artist living in New York City.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gretchen Goss, Mark Hartung, Alan Burton Thompson

Owen Patrick Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

November 4 - 22, 1989

by Holly Goeckler and Myra Mimlitsch Gray

Gretchen Goss is an enamelist who concentrates on large-scale paneled wall-pieces. The size of these pieces is impressive, considering the technical challenges of the medium. The combination of layered, enamel surfaces, patterns, textures and colors is very rich. In some instances, she is able to bring a spontaneous, gestural quality to the work, such as a brush stroke, through the tedious process of enameling.

Ponds (68″ x 25″) is an example of Goss's use of applied shapes and muted palette to create a decorative interpretation of the natural world. This piece succeeds because the palette and subject matter are complementary. Unlike other pieces in the show, Ponds does not attempt to evoke more than a simple appreciation of Formal design and technique. Goss is less successful when she approaches more serious subject matter. Her Memorial Pieces #1 and #2 are styles bits of emotion . In Memorial Piece #2 (12″ x 36″), she presents the ghostly image of a dog in his house, with a title suggestive of love and loss. However, her treatment of a seemingly heartfelt subject becomes banal and merely decorative, insensitive to the shift in subject matter.

Mark Hartung's work consists of forms derived from vessels and toys. His vertical vessels evolve from a direct approach to sheet-metal working, such as rolling long, tapered cylinders and fastening the seams with pop rivets. The compositions of these pieces involve the simple stacking of geometric patterns. The painting adds whimsy to the object; however, the base remains static. The decorative patterns on the objects serve to enhance the metal construction technique. For example, Hartung carefully develops the patterns around each rivet, which both draws attention to and distracts from the simplicity of the cold connection.

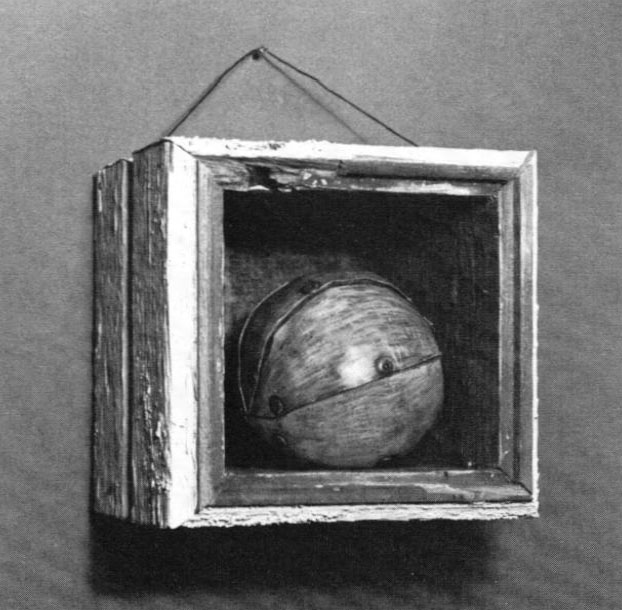

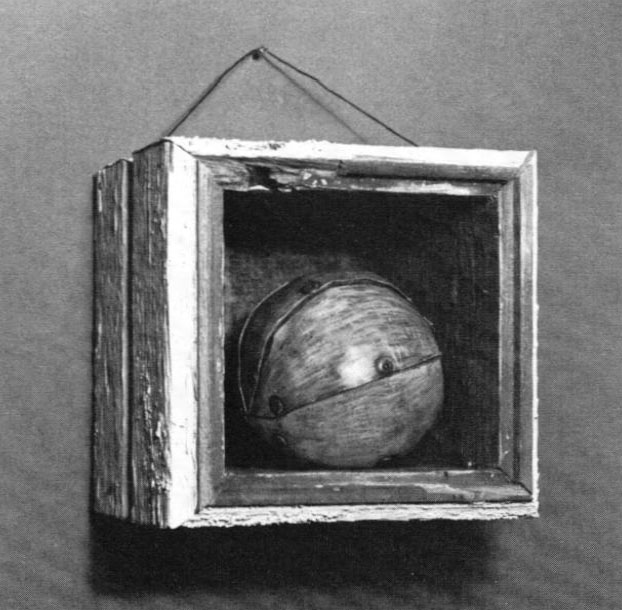

The toy pieces are more successful because they indicate a purpose, while the vessels are incidental, the result of sheet metal manipulation. The playfully painted surface supports the toy reference, while it merely decorates the exterior of the vessel. Hartung's most successful piece is Ball in a Box. The ball is constructed of crudely folded and riveted metal patches and presented in an equally crude box made from found scraps of wood molding. The coarse materials become precious because of their association with the nostalgia of childhood games. The roughness suggests a toy well used and well loved. The box becomes a niche that establishes the ball as an object of importance.

Alan Burton Thompson's work is the most challenging and enigmatic in the exhibition. The pieces are collages of appropriated objects and images in a variety of materials, assembled as brooches. Initially enticing due to its richness, the work results from an eclectic combination of materials coupled with a strong regard for craftsmanship. By gluing opals and gold-leafing plastic, Burton Thompson creates a new context in which the viewer's perception of preciousness can be altered.

Many of the found objects Alan Burton Thompson uses are borrowed from popular culture, such as the plastic rose, the heart and the cameo. Other elements of the work are fabricated by the artist. Tension is established in the ambiguity between the handmade and the manufactured. The pieces are most successful when both are combined so that the viewer does not distinguish between the found and the fabricated and is therefore free to wonder about the meanings of these combined elements, rather than their origins.

The use of recognizable images and universal symbols offers a narrative, where viewers can realize a personal meaning in each piece. However, the repetition of images and materials contributes to a loss of meaning; what could be seen as sincere in one work becomes cliché when it reappears unaltered in different contexts. What results is often formal inquiry with the pretense of meaning. Thompson's ability to combine materials into a coherent form does not always result in the transformation of parts into a whole. For instance, Boat fails to transcend its material origins, remaining a kitsch collage, while Balance becomes an elegant vehicle for metaphorical interpretation. Hoop Ghost, Drift Ghost and Grace I are equally as effective, but one must question the obvious phallic nature of their overall form. This aspect of the work is accentuated by the overlaying of such feminine images as the heart and cameo portrait, which leads one to further scrutinize the artist's intent.

Holly Goeckler is a metalsmith, living in New Hope, PA and teaching metalsmithing at Beaver College, Myra Mimlitsch Gray lives in Philadelphia and teaches metalsmithing at the University of the Arts: Philadelphia College of Art and Design.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Randy Long

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

October 2 - 28, 1989

by Roberta Floden

An ardent student of antiquities, Randy Long visited Greece for the first time this past summer. Inspired by the sculpture, fragments and shards seen on her trip, she decided to adopt marble as her material of choice for brooches and pendants.

Needless to say, marble is rarely used in contemporary jewelry. Few jewelers are prepared to spend the time and effort to learn the slow, laborious techniques - chiseling and carving - it demands. These processes become even more exacting when reducing a material, identified with architecture and sculpture, to wearable size. Nevertheless, using a controlled, designerly approach, she has mastered marble's sensuous, intimate, even delicate properties.

Long does not work marble into a jewelry that contemporizes the material. She doesn't extend marble beyond its proven territory, nor does she reinterpret form and content. Instead, she has examined the traditional functions of wearable and made direct translations into miniature form, linking her very wearable designs with historical and cultural references.

Practically all of the brooches on exhibit are reminiscent of classical marble bas-reliefs. These pieces are secured in gold and silver bezels, with richly finished reverse surfaces. Although they offer few surprises, they resonate with an ageless sense of beauty. Several are "goddess brooches" pink or white marble, female torsos draped in flowing togas. The lines of her Drapery Brooch echo the material of a falling curtain. Others are in the classical shapes of vases, amphora and shields, some carved with archetypal symbols and some embedded with gold.

Corfu Memorial Brooch features a delicately carved feather in a pillar fragment. On the feather, seen only in certain angles of light, are finely chiseled hieroglyphics and a circle of gold nails. This compelling piece shimmers with an air of mystery. Yet, its materials, form and content directly, acknowledge the classical influences from which they are drawn.

Even more successful are two pendants of an abstract nature, hanging simply on leather thongs. Although the designs on these pendants are less identifiable as classical imagery, they are nonetheless born in antiquity. La Figura Otto Pendant is the "infinity" design chiseled in white marble that has been shaped like a "figure eight." Semente Pendant (Seed Pendant) has two rounded, seedlike, symmetrical shapes held together in a gold brace. Because they are more ambiguous in form and universal in content, these two transcend time and place and have an esthetic all their own.

There is nothing contrived in Long's designs. Even her leaf necklace with its 31 hammered-silver leaves, and the matching earrings. are totally accessible. Her stylized, silver "pomegranate" earrings resonate with understatement and simplicity as well.

Randy Long's work is formal, spare, clean and extremely tactile. She has a concern for refinement of form and is most cognizant of the effectiveness of contour and reflection. Her work is rhythmic rather than unpredictable, stable rather than in flux, reposed rather than tense, soft rather than hard-edged. A marriage of thought and process to material, Long's jewelry demonstrates skill, balance and a personal style, rich with historical meaning. While this is an understandably small show, with no more than 12 pieces; it is also one of the more elegant exhibits this gallery has mounted.

Roberta Floden is a writer living in San Anselmo, CA.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Function - Non-Function

Rezac Gallery, Chicago, IL

October 13 - November 14, 1989

by Catherine Jacobi

The Rezac Gallery has organized an exhibition that genuinely discusses the contextual function and the specific function of objects. "Function-Non-Function" approaches function through an inquiry of the essential definition of an object. This is not an investigation of the status or categorization of objects as fine art or craft. Rather, it describes function as what each individual object necessarily does best, autonomously and contextually. The catalog that accompanies the exhibition has an essay by playwrite David Sedaris that augments the premise with a fictional account woven around the topic of function.

Works by Myra Mimlitsch-Gray, Joan Parcher, Gabriele Dziuba, Therese Hilbert, Gerd Rothman and Rebecca Batal reference a metalsmithing tradition while functioning as criticisms of jewelry and ornamentation. Mimlitsch-Gray's Heels displaces cultural concepts of ornamentation and gender representation in a pair of bronze stiletto heels with set garnets in their base and threatening corkscrews at the top. While the cultural function of the average high-heel is essentially a female iconic representation, Mimlitsch-Gray reveals how this can be supported by a real sense of pain and futility.

Works by Michael Rowe, Otto Künzli, Christopher Jünger, Michael Becker, Richard Rezac, Mary Brogger and Robin Quigley have utilized constructive or casting techniques to support the discussions of various subjects. Michael Rowe's "cylindrical vessel" simultaneously references the bowl and the hat. By layering the form with a tinned patina that appears wet, Rowe furthers the duplicity of the form by creating a paradox in the way that it functions it at once repels, as it contains. As with much of Orto Künzli's work, a schism exists between perception and reality. With his Container Künzli presents the perfectly turned, stainless-steel cylinder that, without prior knowledge of flawlessly fitted cover and base, would appear solid.

For other artists such as Tony Tasset, Hirsh Perlman, Kevin Maginnis and Joan Brossa, the traditions of metalsmithing, if at all referenced, are remote in comparison with other premises. Tony Tasset's Cover critical of the way we are or are not able to read objects in an art context. This work approaches the larger concern of the exhibition - how the metaphoric and literal reading of an object can describe its function.

Catherine Jacobi is a sculptor and writer living in Chicago.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cara Croninger

Artwear, New York City

October 17 - 31, 1989

by Carolyn Kriegman

The scale of Cara Croninger's objects-to-wear is assertive, certainly not kind to the self-conscious, insecure or fashion-addicted. It may cut a customer or two out of her market, but it also suggests an artist of adventurous spirit. Croninger's big bracelets, for example, can't be forced through the sleeves of most winter coats, but during their momentary doffings, they do service as small sculptures.

All her forms are simple, consequential. Edges and heft have been manipulated with saw and files, hammer and chisels, polish or sandblasting, Necklaces are also substantial, most often composed of large, abstract, rounded or toothlike, sometimes rectangular or shardlike beads, strung on heavy, knotted, silken cords, whose ends have been selectively frayed. Whether using sheet acrylic or cast polyester-resin, Croninger evolves shapes working from the outside inward. In the stronger pieces, she has layered colors into the clear resin by adding dyes and metallic powders during the casting process. Crosses with embedded lace and newsprint, and pendants with assorted cast-in messages - "change, hope, revolution, my brothers, my sisters, struggle, choice" - though they figured prominently on the postcard invitation for the show, seemed an undeveloped, confusing, even half-hearted political/social/intellectual/religious aside from her other work.

While Croninger may begin with distinct projects in mind, as she casts the polyester blocks, she manages to retain and communicate an enlivening dose of spontaneity in the finished pieces. Machinery and chemistry are inherent factors in this very contemporary group of materials, yet Croninger's interpretation hums with an upbeat, upscale ethnic and historic resonance, not an easy balance to achieve. Many of her works would adapt handsomely to native American or African rituals, or conversely to a ballet accompanied by a Philip Glass score, for that matter. That isn't to suggest for a moment that they're costume.

The predilection for enlarged scale attests to Croninger's gutsy self-confidence, though in opting for bigger, she sometimes is confronted with heavier. No question, her collectors must come to this work with their personal identities in tact. There remains no choice but to dress to the jewelry; it will not accept accessory status.

Carolyn Kriegman is a paper artist and writer living in New Jersey.

Catherine Butler

Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, MA

October 17 - November 17, 1989

by Susan Barahal

Catherine Butler's jewelry can be divided into two groups: those that are primarily decorative, reflecting the artist's interest in nature and fantasy, and those that make provocative statements, rooted in the tradition of social commentary.

Butler's affinity for nature is evident in a series of garden pins that are stylized tributes to flowers. Brass is shaped to form leaves, and antique Venetian glass beads create blossoms. However, in Magic Carpet, she departs from the natural world and touches on the supernatural. Brass and copper have been worked to create a sense of movement. The carpet undulates and captures the few seconds before landing or takeoff. The pin is designed to be worn on the shoulder, which appropriately serves as a launch pad or landing strip. The artist's ability to suggest movement is rivaled by her intricate rendering of the carpet's surface. Ornate patterns are etched and filled with colored epoxy to create the magical, jewel-like designs of Oriental rugs.

It is when Butler focuses on the real world that she is most effective. Two neckpieces, Factory Farmed Chicken and Free Range Organic Cornfed Chicken, call attention to the controversy of using chemicals in farming. Factory Farmed Chicken consists of uniform chicken parts that appear mass-produced. Each silver piece is colored with purple and blue spots, exaggerating their inorganic nature. These parts alternate with dull, metal, rectangular shapes. Written on each is the name of a chemical, hormone or malady. The words are stamped by using commercial letter punches, recalling military dog tags. And, like dog tags, these plates confirm that the chicken parts, like the soldiers, have been processed and serve as positive identification. In contrast, Free Range Organic Cornfed Chicken is plump and healthy. Standing with outstretched wings, it is living proof of the benefits of organic farming.

The role of the farmer is quietly acclaimed in another neckpiece, Hidden Farmers. Earth-colored beads form a multistrand necklace. The beads' colors, shapes and abundance seem to refer to the earth, its grains and harvest. But, while the body of this piece suggests the essence of the land, it is the clasp, depicting figures of farmers, that symbolically and literally holds everything together. Fabricated from copper sheet, this group of jovial farmers stands proudly. Each farmer holds a shaft of wheat, like a patriot waves the flag. However, there is no fanfare. The farmers, functioning as a clasp, are worn at the back of one's neck and are "behind the scenes" in this testimonial to the archetypal American.

Susan Barahal is the Decorative Arts Editor for Art New England Magazine and teaches art in the Boston Area.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Silver New Forms and Expressions

Fortunoff, New York City

October 2 - 22, 1989

by Janet Koplos

The tide of Fortunoffs competitive and invitational silver exhibition is perfect. The "New Forms" part indicates an unrestricted play with materials, while the "and Expressions" phrase opens the door to art aspirations. Underlying them both are the big questions that no one wants to ask because no one can answer them: Is there a form that defines our time, as Art Deco captured the streamlined modernity of the Jazz Age? What expresses late 20th century?

The works shown at Fortunoff are characterized by the appeal of an heirloom without the allure of standard forms. "Form follows function" has been abandoned, and not replaced by another form-motivating concept. Filling this conceptual void, by and large, is conspicuous virtuosity, a showy "how" instead of "why."

That's the case in both the juried and the invitational parts of the show (the invitational works are distinguished on the exhibition price list and in the catalog, but not on the display labels). Perhaps it can be seen with particular clarity in the first-prize winner, a teapot on stand by Charles Adam Crowley. It would seem that Crowley won for an unexpected way to store a teapot. It's not "sensible," but it's striking, and in our complex and transient relationships with the objects that surround us, that is (completely apart from the question of whether it should be) a measure of value.

Nearly all the work in this show can be praised for technique and for imagination, and much of it is admirable if judged within the narrow confines of "contemporary metalsmithing." As rare in this show as in the world at large are examples of well-developed form that is beautiful and/or practical.

Among those is Yosuke Inoue's coffee pot. It's hardly what one would call a standard form. It makes me think of a butler with sclerosis. The extreme curve gives it a certain energy that is held in check by the propriety of the surfaces and materials. I think the only straight lines in this pot are the lid hinge, at the top back, and its visual echo, the back edge of the base. Just as these two lines resonate from top to bottom, so the plethora of curves repeat or reflect each other. All this interest does not violate the requirement of function: the pot still looks as if it would be easy to use. Inoue earned an honorable mention.

An equally successful coffee server by Thomas L. Martell is another well-deserved honorable mention, although one wonders at the $13,500 pricetag, Martell makes use of a wide array of geometric forms. The vessel and its handle are both vertical rectangles but are not perfect mates - the handle is taller. The black of the handle against the silver of the container reads as negative/positive, outline/solid. Details show exquisite restraint: the spout is a tiny teardrop-shape opening in one corner; the lid is a perfectly circular disk. The whole is saved from preciousness by the slightly pneumatic profile, which gives it the breath of life.

A number of the juried works are humorous. It's interesting to see confidence to be light-hearted even though high-priced. This esthetic seems to derive from those heady days of nonprecious materials, but this show requires silver, so the material doesn't justify such handling. Still, if one refuses to think about cost, one can enjoy the wit of Mary Margaret Zeran's Farm flatware, shaped like rakes and shovels, or Kee-Ho Yuen's tea service modeled on paper bags (the third prize winner). The complex dynamism of Susan R. Ewing's Bull's-Eye Teapot leaves that organic image far behind leaning toward Pop art road signs. Jean Mandeberg's Split vessel is a simple bowl divided by seams with what appear to be interlockable tabs; the disjunctiveness gives it visual impact without precluding usefulness. On the other hand, the belabored construction of J. Steve Jordan's basket made of silver "quills" takes it out of the functional realm, but earned him the second prize anyway.

The invitational section includes more works by fewer artists (17 as opposed to the 20 juried entries). Two of the three judges for the exhibition - Jamie Bennett and Fred Fenster - are among the invitees. Kevin Stayton, of the department of decorative arts at the Brooklyn Museum, was the third juror.

Many of the invited works serve, as expected, as touchstones, and others represent the familiar esthetics of some of the best known names in American metalsmithing. Two exemplary works present an interesting contrast: Alma Eikerman's Mocha Pot and Chunghi Choo's Teapot are both small, irregular globes, restrained in both form and decoration, but the mood that they express is quite different. Eikerman's pot is a graceful, full, satisfying shape, precious because of its size. An ivory grip on the lid and a length of ivory on the handle are primarily functional, but in their precise relation, they also visually extend and balance the larger volume of silver. The pot, gourd-shaped to the extent that its outline is essentially triangular, is inversely reflected in the spout (starring fat and tapering to a small mouth) and the handle on the lid. Those three forms offer a continuum of triangles, starting at the organic end of the scale and ending at the machined end. The pot is a union of neat, distinct, balanced parts.

Choo's work, by contrast, consists of pot and spout as one seamless whole, and a lid that seems cut from the same fabric. This gives her pot a sweeping, uninterrupted line. That line is reiterated - or completed - in a flamboyantly oversize handle that doubles back on itself in a compressed S-shape. The effect of the whole is less like a teapot than like a tropical bird with a flowing tail, an association that is carried through in the jaunty feather-comb that flips back from the lid. The handle does not appear to be convenient to grip, but it makes a wonderful image.

Well-known metalsmiths showing characteristic works include J. Fred Woell, Helen Shirk, Ronald Hayes Pearson, Richard Mawdsley, Stanley Lechtzin and Arline Fisch. John Marshall's Bloome flatware (service for eight) is one of the more innovative approaches to function. The bowls, tines and blades of this flatware are consistent, but the handles of each place setting are different. Marshall seems to be freely playing with form. If he were a silver company designer, this might have been eight new designs, but because he is making them himself, a single five-piece place setting is sufficient to realize the idea. Like Choo's pot, this flatware tends to be more interesting than practical - it would be difficult to clean - and makes a strong impression as an exhibition form.

A jar and a casserole by Olaf Skoogfors are included. One wonders what the jurors meant by this inclusion. The forms are classic and timeless, yet few metalsmiths make classic and timeless objects today. If they did, they'd probably be attacked as commercial and unimaginative. Are these beautiful objects meant to comment on the excesses elsewhere? How can we regard "New Forms and Expressions" from a long-dead artist?

At an opposite pole From Skoogfors' classicism is juror Bennett's The Seeker. It's a sculpture, I suppose. At least it has no apparent function. It consists of a diminutive rendition of a checkerboard-top Parsons table finished in silver leaf. A vase with a dead stem in it lies on top. This object is really more pictorial than three-dimensional. It has a peculiarly passive and nostalgic tone. One wonders why it's an appropriate inclusion in this exhibition. Its minimal amount of silver qualifies it for the theme of the show, but it is definitely not functional and even measurably less decorative than the hackneyed surrealism of Keiko Kubota Miura's place setting. It's not entirely successful formally because it is so much weaker from the side (one tends to be conscious of the space underneath the table) than from the top view. But it has nice qualities of mystery and suggestiveness that make it worthy of consideration as an art object. There are lots of appropriate venues for such work, but a holloware and flatware exhibition at Fortunoff is nor among them.

Fortunoff produced a Free black-and-white catalog of the exhibition, including a jurors' statement and a brief essay by Vanessa Lynn. The company plans similar exhibitions in 1990 and 91.

Janet Koplos writes frequently on three-dimensional objects.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Joan Michlin: Current Metalsmithing

John Marshall – The Birth of Time

Rebekah Laskin: Material Voice

The Ardagh Chalice

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.