Metalsmith ’90 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

31 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1990 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Marjorie Schick, William Underhill, Joy Scott, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Marjorie Schick: A Retrospective

School of Fine Arts Gallery, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

January 19 - February 9, 1990

by Lydia Brown Finkelstein

Marjorie Schick's 26-year review of her work in various metals combined with paper, string, rubber hose, raffia and wood guided viewers through a series of metal and emotional experiences that, at times, verged on chaos and anxiety, cornball jokes and sharp urban wit, sublimely edited introspection verging on spirituality, then grounded by reassuring ritual.

Over 100 works dating from 1965, when Schick received her MFA with distinction from Indiana, up to 1989 were installed by the artist for the event. Since Schick has stated she creates her body sculptures with the human figure in mind, the presentation of her work, without mannequins or models, became as important as the individual pieces themselves.

Her recent total body designs of multiple painted plywood shapes, joined with colored string and dowels, resembling American Indian backpacks or priest's vestments, were suspended from the ceiling, hung or projected from the gallery walls. Several angular neck-and-shoulder sculptures of riveted and painted wood dowels seemed incomplete without the presence of a human personality to fulfill the destiny of a ritual object for worship, exploration or hunting.

The fact that these body works are both finished, and yet not finished without the body, creates an esthetic paradox that sets Schick's work apart from functional jewelry created to be worn by a patron who wants adornment without involvement.

Today the primary experience that motivates feeling, perception and action has been co-opted by the mass media which selects, edits and interprets events and relationships for us, the voyeurs. Schick's attitudes and belief systems that delve into the inner stares of reality. What is important about Schick's work is its utter nonusefulness, but intentional seriousness abstracted experience.

In the 1970s she began constructing oversize brooches, cuffs and neckpieces that she calls her Cycladic Series. These polished brass and copper shapes frequently combined with a coiling and sensuously currying black rubber hose are sculptures to be worn by an archetypal figure in a dream. One can certainly imagine them worn by dancers in a Joffrey Ballet sequence. The neoclassical motif of sleekly constructed geometric interlocking shapes, smooth surfaces and rubber convey a cerebral sexuality ordered by the hand of the artist. Instead of industrial objectivity, one feels drawn into an encounter between desire, control and capitulation.

The early work of the 1960s, started at Indiana, is openly expressionistic, mixing silver wire, melted and pitted bronze and brass in sometimes gritty images that suggest intense emotions of confrontation and contact. Loops of wire lengths are twisted, wrapped and soldered straight onto solid and open textured forms that have an objet trouvé feeling.

Her 1967 Wheatfields necklace is vibrantly alive with its looped and bent silver wires waving in the wind. Another early piece, a pectoral shield with its parallel bronze and brass straight lines soldered to a curving frame, is a feminine protective vestment suggesting the intuitive needs of the inner self-protected by rationalist outer behavior, the "thinking woman's" body sculpture.

Another Schick persona slowly emerges from such early work. Her 1980s "stick" designs encompass negative open space defined by slender dowels, cut and riveted to one another in zig-zag, round and pick-up-stick patterns. The Mondrian-like colors of the rods send off the energy of a charged conversational encounter, punctuated with pauses and looks. Wood, a living organic material, becomes a symbolic substitute for the human voice. If art has the power to transform with evocative images, Schick makes a series of witty, and ironic, references between body language versus body "sculpture" with her primary colors and optic impact.

Schick's prodigious, and outrageous, creative energy mock the contemporary American art scene dominated by boutique technology, mass marketing to billionaires and indifference to the human condition.

Lydia Brown Finkelstein writes on art, craft and design from Bloomington, Indiana

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

William Underhill

Garth Clark Gallery, New York City

September 12 - October 7, 1989

by Janet Koplos

What are these bronze forms - vessels, sculpture, architecture, landscape? Their real size limits them to the first or second, but they might imaginatively be the others as well.

Scale is the most obvious of the several difficult issues in the bronzes of William Underhill - issues that reflect irresolution of purpose. Some works seem to cry out for greater dimensions. Lidded Vessel consists of two vertical slopes bridged by a plank top, which bloats to a pendulous bottom. One can imagine this in monumental scale, as an industrial retort, a landscape reclamation or an ancient funerary structure. The tide, however, squelches such flights of imagination.

If these are vessels, they are far from ceremonial. Their form (setting aside the question of material) gives them a ponderous weight. They seem not meant to be moved. They sit squat, even when they have legs. They meet the table or pedestal with a thud. One might imagine that a suction seal has formed and they'll be impossible to lift. That's not suitable for a functional vessel, but it's fine for architecture or landscape; the form would seem earthbound, serene, stable and timeless in that context. The bronze material and the various patinations suit those notions, and Underhill sometimes chooses titles that seem equally grounded and aged, such as Mastaba.

The key to form is geometry, an ancient means of ordering the world. Some chalice or fontlike works are variations of square and cube, with one part or another cut away. These elegant variations are best seen in quantity: one alone looks a little stodgy, but in a group, seen as illustrations of the infiniteness of an abstract concept, they have considerable grace.

Yet Underhill seems to be chafing against the limitations of scale and geometry. Geometry is an abstraction more perfect than nature, yet he makes his bronzes imperfect by alluding to the passage of time. He's not content with austerity, so adds texture to idea. But such alterations are too much like busy-work to have much impact. Underhill's bronzes are intelligent and sensitive, yet they're arbitrary rather than inevitable, made rather than born. His expression of geometric variation, for example, could just as eloquently be realized in a drawing.

But in one work he escapes limitations and slips into the infinite. In Danu's Sister, the natural and the abstract are perfectly balanced. Contributing equally are a timeless stillness and a sense that this object is a vessel and more. From the front view, it's a conception of human geometry (as pure as Brancusi's Torso). From the top view, it's a square container with an irregular interior. It has the same interaction of curve and line as the others, but it's alive with suggestion, allusion that animates the weight and hardness of the material. Scale is appropriate to the allusion: small enough to be delicate and evocative but large enough to be a generous container, like the female body. It's the achievement of this work that demonstrates the smaller compass of most of the others.

Janet Koplos is a writer specializing in three-dimensional objects.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Art: Jewelry & Metalsmithing

College of Design Gallery, Iowa State University, Ames, IA

September 18 - October 6, 1989

by Jean Sampel

Encyclopedic was the thought that lingered after enjoying this extensive exhibit. Organized by Professor Chuck Evans, it showcased the versatility of 42 artists with 142 pieces. Sculpture and holloware dominated, including the monumental strength of Janice Cunningham-Koury's two constructed copper and brass sculptures with brass leaf and patinas and David Pimental's large segmented circular wallpieces, patterned by controlled (resist) patinas. In contrast was Obi Mock Urn by Hal Hasselschwert, the most sensitive and gracefully innovative of his seven enamelworks. Also noteworthy was the elegant electroformed and plated bowl by Chunghi Choo, with constructed (and plated) ladle, and the simple but dramatic double-walled cups by Brigid O'Hanrahan. Visions of ceremony surrounded the raised and sculptured copper vessel, enriched with iridescent beads and feathers, by Lisa Kupfer, while the three sleek sterling rattles by Ann Wright seemed destined for royalty. The works of masters Heikki Seppi, Fred Fenster and M. Avigail Upin always invite examination. The wearable art was a media event, with the many materials explored seeming well-suited to the myriad concepts behind the work in this very accomplished collection.

When asked why and how he came to organize such a show, Evans responded that he wanted the residents of the area as well as his students to see a broad spectrum of contemporary metalwork, and the College of Design was willing to finance this idea. Since this invitational exhibition showed metalwork from across the nation, which encompassed practically every technique and material, it was quite interesting to note the absence of any "regional" style or concept, reinforcing the notion that artistic motivation and inspiration are internal, borne of experiences, perspectives, intention, commentary and/or vision, and are not to be categorized by place or process. Evan's past research on his book Jewelry, Contemporary Design and Technique made it possible for him to pull this collection together - a virtual primer of excellence for students of the medium.

Jean Sampel is a goldsmith and owner of the Jean Sampel Studio Gallery in Des Moines, IA.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Joyce Scott: Beaded Jewelry and Small Sculpture

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

January 8 - February 3, 1990

by Roberta Floden

Perhaps because they were so extensively used during the craft heyday of the sixties, beads somehow lack credibility as a serious art medium. Yet, despite such reservations, you can only be delighted at the unpredictable, totally unconventional, bead jewelry and sculpture of Joyce Scott.

There is something subversive, excruciatingly ironic about her art. Using an ancient form of ornamentation, Scott creates bold, oversized jewelry with seductive, jewel-like surfaces that jolt the viewer with their completely nontraditional content. Her pieces are laden with social concerns and issues. The messages may not be hers alone, but surely they are unique in the realm of art jewelry.

For the most part, Scott's work can be considered an ingenious theater of ideas - tense, disconcerting, but not without levity. It has similarities to Pop Art, not only in the use of beads, but in appropriating political and social subject matter, found objects and the immediacy of context. Her work is often peopled with cartoon characters that speak a language imbedded in oppression, racism and feminism. Her narratives use recognizable household imagery to present broad outlines of events, encompassing their causes and consequences. The results are unusual, even absurd, juxtapositions, replete with dimensions that force the viewer to respond intellectually, as well as emotionally and esthetically.

Scott weaves and collages beads, along with fabric, bits of material, photographs and plastic. Her recent Jonestown Series, (part of the 1987 Philbrook Museum of Art's "The Eloquent Object" exhibition, shown locally at the Oakland Museum) consists of four brooches commemorating that horrifying tragedy in Guyana. Reflected in her pieces Kool-Aide Kocktail, For the Souls, The Double Cross and The White Boy's Gone Crazy is her rage at the white spiritual leader, Jim Jones, who ordered his mostly black followers to commit suicide by consuming poisoned drinks. By virtue of this quartet, in which bones, hair, pins, tree bark, stones and a razor are symbolically fashioned to recreate the historical event, Scott has extended the limits to which jewelry can be made forcefully political.

In the current exhibit, Scott has created beaded abstract neckpieces and earrings dong with her signature pieces - narrative wearable art and sculpture. Rooted in feminist archetypal themes, these latter pieces are drawn from Scott's deep feelings and trenchant intellect. Here, Scott takes as her subject matter her experience as a woman, asking the (female) wearer/viewer to contemplate her own experiences, as well.

No. I Mom is an approximately two-foot tall, three-dimensional sculpture. On a green-beaded kitchen chair, sits Mom, the soul of domesticity. Her naked body is shiny pink leather, her hair blond curly fabric, her beaded face glowing and smiling, while giving birth to one gold-hued beaded baby from a beaded vagina, holding a black one to her nipple, and sitting passively while two others, one red, one brown, climb on her chair.

In Party w/writing, 1989, you "read" the oversized necklace, entirely made of beads, from left to right. First comes the word "BEFORE," then the blond head of a man saying "PARTY!" Then, amidst the words "Foxy" and "Get Lucky," come a woman's red dress on a hanger, other party clothes, a shoe, a frontally nude woman with a smile on her face, and then a procession of undergarments - a corset, a slip, pantyhose. Then comes the same blond man's face, only this time smiling as he holds a liquor bottle up to the woman's mouth. The message may be simplistic, but to see it in a collar made up of row upon row of beads is stunning.

A more spiritually conciliatory theme is projected by Mommy, Mammy with writing & photos, 1989. It begins with the beaded word "Mommy" and ends with the beaded word "Mammy." Hanging from these words are two black-and-white photos, one of a white and one of a black babydoll encased in plastic and surrounded with beads. Overlaying them is a sculptural figure of the Virgin Mary, with a far wooden-bead head and a gold crown. In her arms she holds the color photo of a white baby, while a red- and a black-beaded child cling to her gown. When you consider the idea that underpins the collar - we essentially have one mother, we are essentially one people, regardless of the colors and the images we project, thus making the divisions among racial groups arbitrary and without merit - the necklace becomes a charged religious talisman, alive with meaning.

Provocative politics aside, Scott works within a technically fascinating framework. Her subtle sense of color, and her three-dimensional beadwork juxtaposed with fat beadwork, lend these pieces freshness and vitality. It is a jewelry based on compositional and formal elements that uses and manipulates the intrinsic surface reflectivity and opacity of beads. Scott's use of disparate patterns, textures and shapes to form complex visual images stretches the employment of beads to the limit.

None of Scott's neckpieces is quiet. Many are confrontational. There is no understatement here. Some amuse, some annoy, some even shock. You absolutely have to agree with her politics, let alone her style, to consider wearing one of her collars. They may be unconventional in content and high-profile in look, but they involve you in multiple layers of sociological and psychological insights.

Roberta Floden is a Marin County, CA, artist and theater critic.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Clara Yares

Joanne Rapp Gallery/The Hand and the Spirit Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ

November 1 - 30, 1989

by Lynn R. Rigberg

Clare Yares looks for that perfect balance that achieves polarity between the elements of his jewelry; a tension that sparks the work to life. Symmetry and rightness of proportion, usually suggestive of a rather straightforward metallurgic rhetoric, are mysteriously outdistanced.

A circular brooch, just under three inches in diameter, presents a good example. The slightly concave, round, silver shape surrounds a slightly raised, bevel frame. Into this round is set a dish-shaped center of blue enamel. A small gold sphere rests on the silver's raised inner edge, tucked comfortably next to the bevel.

The enamel color is revealed in its graduated intensity as it approaches the center of the concave shape; encased in silver, the heat of the enamel is contained, alive, vibrant. Moreover, the bevel, within which the blue is captured, is itself lined with gold, and so the gold very subtly reflects in the enamel. Thus, the relationship between elements of silver and enamel is imperceptibly, and most effectively, bridged by use of the gold sphere in juxtaposition with the concave enamel. The uncluttered character of design elements in the brooch, says Yares, is a consideration of the fact that "there has to be room for the background, being a brooch."

A concave, silver-hinged bracelet, three-quarters of an inch wide, with fine gold, convex bars set along frequent and equal intervals, is an invitation to participate, to discover, even to explore for tactile interest. The bracelet hinge is operated by a minute flathead pin. The pin is delightfully, confidently responsive to gentle outward pressure that pulls it halfway out, releasing the lower half of the bracelet and allowing it to fall open. "Jewelry," says Yares, "to be appreciated, must be handled."

The bracelet also presents another example of the quality of mystery in Yares's work. The observer has an intuited understanding that the elements of design are somehow perceptively delimiting. Behind that sense is the artist's idea: the arcs of gold, unconsciously continued in the imagination, have their real meeting place at the center of the bracelet.

Yares looks to realize a synergy, a "friendly association between fully evolved elements - including the wearer." A constant force is in action in Yares's pieces. But if the effect is mystical, the power behind it is an apotheosis of intensive intellect, disciplined application, and an inspiration for what Yares understands as "balance that ends up as a state of grace; not just what is but what it does."

Lynn R. Rigberg, who lives in Scottsdale, AZ, writes on the arts and teachers at ASU.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Work of Angels

Masterpieces of Celtic Metalworks, 6th - 9th centuries A.D.

British Museum, London

November 29, 1989 - April 29, 1990

by Deborah Norton

"The Work of Angels," an expression first used by Gerald the Welshman in the 12th century to describe a Celtic illuminated manuscript, was chosen as the title for this exhibition because it applies equally well to this outstanding collection of jewelry and religious objects. There is also evidence that decoration for these ancient books was derived from fine metalwork, thus making the title doubly appropriate.

Although made on an island on the western tip of Europe, this work was not produced in isolation, as the Irish Sea enabled easy contact between Ireland and Britain. Traditional Celtic metalworking techniques and styles were augmented by outside influences that resulted from trade and travel. From the sixth century, Irish missionaries traveled abroad to France, Switzerland, Rome and the Holy Land, while Anglo-Saxons and Franks were known to have visited Ireland.

Jewelry played a significant role in Irish society during this period. Brooches were universally worn - by men on their shoulders and by women on their breasts - and the possession of fine jewelry and metal objects was a mark of status and success. An eighth-century Irish tract on status specifies the fine metals and inlays appropriate for kings.

The Hunterston brooch, made in the late seventh or early eighth century, is an extremely fine example of the ultimate status symbol. Made of gilded silver (a very valuable material at this time, as there was no regular supply of precious metals available in Ireland and only one solid gold brooch is known to exist), it was cast in a two-piece mold rather than the lost-wax process popular two centuries earlier. Its form is the traditional penannular ring with triangular terminals, but the usual gap at the bottom is filled by a decorative panel.

The filigree on each of the panels depicts interlaced beasts executed in beaded wire (a handmade wire was hammered along its length between dies to produce a beading effect) and filled with gold granulation. The bird heads clinging to the outer edge of the ring are derived from Anglo-Saxon jewelry as is the exceptionally crisp filigree. Like other brooches of this era, the reverse side is decorated with the same motifs, techniques and level of complexity as the front. The lack of gemstones in the Celtic world is compensated for in this piece by the use of amber. In other objects, enamel and glass inlay, especially millefiori, was used to achieve the polychrome effect that revolutionized Celtic metalwork in the seventh century.

When Christianity was introduced to Ireland in the fifth century, the techniques and motifs of secular metalwork were employed for ecclesiastical objects. Like the Hunterston brooch, the Derrynaflan chalice uses amber and filigree, but in this piece, made a century later, the animals are more naturalistic. Each panel contains a single beast, often a griffin, that is an elegant sketch rather than a curvilinear design as in the earlier brooch. Like all large and complex objects made at this time, this chalice was created in small segments that were later assembled using riveting as the main joining technique.

This exhibition concluded with an intriguing display of tools, molds, crucibles and even "sketch books" (designs incised on stone) that gave valuable insight into the fabrication process.

A scholarly catalog with color photos is available for £12.95 from the British Museum, Great Russell St., London WC1, England.

Deborah Norton is a contributing editor to Metalsmith living in London.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Fifth Juried Biennial Exhibition, Washington Guild of Goldsmiths

Partners Gallery, Bethesda, MD

December 1, 1989 - January 1990

by Lenore D. Miller

Since 1978, the Washington Guild of Goldsmiths has enabled a group of dedicated men and women, who share a passionate interest in metalsmithing and jewelry design, to network, exhibit and learn more about their craft. "Metalwork '89" is their fifth biennial, featuring jewelry, sculpture and holloware. Juror Alan Revere's statement notes the tough decisions he faced in selecting from many worthwhile entries. Excellence in the areas of design impact, originality and craftsmanship were cited. The 10 award winners were selected by Rosanne Raab on the basis of creative expression and fine craftsmanship. Her catalog statement raised the question of the paucity of vessels, flatware and the limited use of precious metals. Although wearable jewelry such as pins and necklaces predominated, there were a number of functional and decorative statements, including a lamp.

The juxtaposition of unlikely textures and the incorporation of materials usually associated with more mundane or industrial usages seem to be trends in contemporary ornament. Gretchen Raber, a pioneer in this idiom, is but one of the artists whose inspirational designs come from mechanical tools and space-age materials. Eric Margry's rings poetically unite opposites - rubber, gold and diamonds - with a modernistic flair. Streamlined design in the constructed brooch by Janet C. Peters recalls the Art Deco era.

Educational workshops sponsored by the Guild throughout the year explore technical and esthetic aspects of metalwork. The impact of these workshops was reflected in Mildred M. Ehrlich's granulated earrings and in Fred Fenster's columnar pewter candlesticks.

Several functional pieces were exceptional for their quality of design. Yvonne Arritt's pasta serving set of fold-forged and formed sterling silver were most impressive for their timeless design quality derived from the seamless confluence of material and form. Betty Helen Longhi's letter opener recalled the organic, flowing line of Art Nouveau. Likewise, Joan F. Levy's Fan 1 pendant mixed materials with an eye for linear grace and decorative enrichment. Allowing the materials to speak eloquently, Fridl Blumenthal's sculpted spiral, forged and fabricated, set off an unusual free-form rutilated quartz.

Other pieces in the show evoked the mystery of organic growth patterns and alluded to the romance of landscape. Marie H. Susinno's Summer at the Beach reticulated silver pin, which exquisitely balanced the color and shape of an opal with a crested form like a wave, evoked the joyous feeling of floating on the sea. Patricia M. Perito's Watermelon Slice pin similarly shared an ability to elicit an emotional response through whimsy and simplicity of form. Susan Portner's unique approach to carved onyx invested simple designs with great elegance. Eun-Mee Chung's brooch Through the Flower #4 Fence exhibited complex spatial and textural manipulations more commonly associated with mixed-media painting.

The inspirational role of tribal art on jewelry design was evident in Roger Kuhn's African brass goldweights mounted in textured copper. These solid looking pins have titles that reflect an interest in archaeological layering. Another piece that exhibited a tectonic dynamism was the isosceles-shaped pin by Seymour Jeffery.

Komelia H. Okim's influence on younger designers has produced some strong work. Her excellent craftsmanship was represented in this show by containers and vessels that exhibited great stylization and wit. Another interesting trend was the use of metals as if they were decorative gemstones. Works by Rosemary Gould/Tom Dulz and Sheila Marshall fell into this category.

Keith Lewis's captivating character studies make one forget all about arbitrary distinctions among the fine arts. The power of this artist's work lies in his ability to achieve the "alchemy" of bringing inert matter to life. Movement and whimsical gesture unite in his excellently crafted metal brooches to produce a unique statement. The details lavished on his pieces, such as the cleverly shaped fasteners and private messages, which can only be seen by the wearer, offered an endearing originality. Dancing Male Nudz, of sterling silver, brass and depletion silvering, epitomized an expressive though minimal gesture.

The tour-de-force carousel by Michael R. Schwartz ushered the viewer into the realm of fantasy and pushed figuration, romance and animation to its decorative limits. The animated, lighted and musical mixed media piece mimicked sculptural monumentality, despite its appearance as an extravagant toy for the romantic soul.

Lenore Miller is an artist, lecturer and curator of art at The Dimock Gallery, Washington, D.C.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Short Runs

MOTTO, M D F, Cambridge, MA

by Daniel Jocz

A new phenomenon: artists who traditionally make jewelry are designing tabletop accessories and small furniture in short-run production. I became aware of this recently, at the opening of two new stores: Motto and M D F, featuring furniture and accessories, both owned and run by Jude Silver. Many of the works in both stores are done by the same artists. Silver's knack for presentation lends an aura of excitement as her passion for metal construction and related techniques sets the tone, while her love of Deco sets the general style of work presented.

Kirsten Hallthorn's earrings and brooches tend towards simple, pleasing comparisons between materials, shapes and textures, and through the use of imaginative associations, she generates visual interest. This free association approach translates to her tabletop accessories as well. Cleverly using rivets and rings to connect acrylic and metals, she plays one material off the other. For example, the more massive, bouncy, tubular-rubber base for an acrylic bowl seems just right when compared to the detailing of the riveted handles. A sense of fun prevails throughout her work. The growth metaphor and the imposed versus natural phenomenon of textures and shapes that she uses so well work better in the simpler pieces. This discrepancy may be due to her wish to keep a look of individuality and the mark of the handmade in a production situation.

Though Boris Bally's work resides on the borderline between straight-forward design and exploratory craft persuasion, the sense of use in his work is requisite. His candleholders, corkscrews and flatware have an inventive edge. While his feel for engineered design comes through in his jewelry, it is particularly evident in his blending of art and usefulness in corkscrews and candleholders. Though many of the flatware and sterling silver candleholders are driven by a functional schema, others, such as his sterling, aluminum and concrete candleholders, transcend everyday usefulness. It is the symbolism - hand holding a disk, ring with ball hanging in the center of the candleholders - that adds a twist and suggests a higher aim. An enigmatic quality drives one to contemplate these objects.

Candleholders constructed from sterling, anodized aluminum and concrete have wire twist fasteners, a touch of overt handwork to complement the machined formalist look of the holder itself. The use of concrete in the base and top gives the holders weight, both literally and visually. While his stacked, modular, sterling silver candleholders with their calculated sense of elegance readily imply a design for a production, they do not have the impact of the other candleholders. The repetitive silver forms lend themselves to production but lose the sense of daring evident in his other work.

Lorili Hamm makes sterling silver, acrylic brooches with subtle scratched finishes and heat-generated colorations. With these brooches, constructed of superimposed shapes with cutouts, she develops a sense of quiet and mystery. Using rivet fastening to her advantage, she creates an esthetic counterpoint. Hamm's venture into the world of small furniture and tabletop accessories design has mixed results. Her Callisto table is direct constructivism, bold in concept. Structural connections are direct, adding power through simplicity in construction. The glass top and the anodized aluminum tubular legs of this table have commensurate purpose. This directness of construction runs through Hamm's furniture and accessories. Forms that don't have a structural role in her mirrors and frames such as cones and pyramids, tend to confuse; are they fantasy elements or just post-modern? The use of these puzzling elements obscures the real strength in the works. One hopes that the bold strokes seen in Hamm's pedestals and tables win out.

Individual pieces stand our among the work of Bally, Hallthorn and Hamm, as well as other jewelry artists who are exponents of this designer trend, but there is a struggle between a craft "hands-on-approach" and a design for production method.

Daniel Jocz is a metalsmith/jeweler living in Boston.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Artful Chair

Target Gallery, The Torpedo Factory Art Center, Alexandria, VA

January 21 - March 11, 1990

by Jan Maddox

This exhibition was one of a series planned to encourage artists to use a functional object as a means for esthetic expression. Twenty-two artist, both juried and invited, were selected by curator Dickson Carroll. The most cautious examples were made by several furnituremakers, functional and well designed. In a few cases, the function seemed incidental and the artists simply used a chair instead of a canvas as a basis for painting, collage or assemblage. Other pieces more fully explored the possibilities of making an esthetic statement within the restrictions of the given function. The distinction between the two approaches at first seems to be one ofemphasis, but to fulfill the declared intent of the show, it had to be fundamental.

Animus by Donna Reinsel used a welded reinforcing rod framework and pieces of sheepskin with a long columnar spine topped by a sheeplike head. It seemed anachronistic, a throw-back to primitive form, with a sense of personality and reality resulting from its deliberately crude construction and contrast to the "nicer" pieces around it. Work Chair by Scott Brazeau also used reinforcing rods, "found steel," but with very different results. Playing with a series of interesting cut-outs that explored positive/negative shape interaction and the progressive development of the shapes, it was perhaps the most purely sculptural of the pieces, and one had no urge whatsoever to sit on it. Wing Chair by Robin Youngelman was symmetrically constructed from a series of interlocking arcs of welded steel sheet. Despite the cold, hard material, the chair looked functional and even comfortable. The two pieces by F.L. Wall were very cool, simple, geometric shapes, but with an unexpected element such as a bone for the back or pitchfork tines to add to an element of surprise.

Among the more amusing pieces were two artists looking at the 50s. Shag Herndon's '49 Ford Auto Sofa was the rear end of a 1949 Ford, with an upholstered seat of shiny red vinyl inserted where the trunk had been. Eric Margry took an old hair dryer, dressed it up with new paint, added a brand new square chair of bright pink formica with little turquoise kidney line drawings and a red vinyl seat and changed it into a lamp. Copies of the National Enquirer, etc., provided the proper ambience for his Gossip Information Chair. Totally, tastefully, tacky.

There were relatively few examples of jewelry. Linda Hesh's earrings, Sixing Pretty, were whimsical and wearable. Gretchen Raber constructed a one-quarter-sized maquette for a dining chair that is a variation of one of her brooches in material, color and design. As a longtime admirer of her work, I enjoyed watching a brooch become an upholstered chair as she adjusted her design ideas to deal with the change in function. Thomas Mann was represented by Techno-Throne, a piece that was also closely related to his jewelry. The missile enthroned on the chair makes a strong comment about the influence of the military industrial complex in our society.

I came away wishing that more of the artists had explored truly outrageous ideas or tried to change my attitude about "the chair" as an ordinary functional object. You can always second guess a curator, and I have since seen several chairs that might have made the exhibition more exciting and innovative. Although the show may not have explored the expressive potential of the chair as fully as one might have wished, it certainly was a worthwhile starring point.

Jan Maddox is a metalsmith living in Bethesda, MD.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Curtis LaFollette: Recent Works

Bannister Gallery, Rhode Island College, Providence, RI

February 1 - 22, 1990

by Daniel Jocz

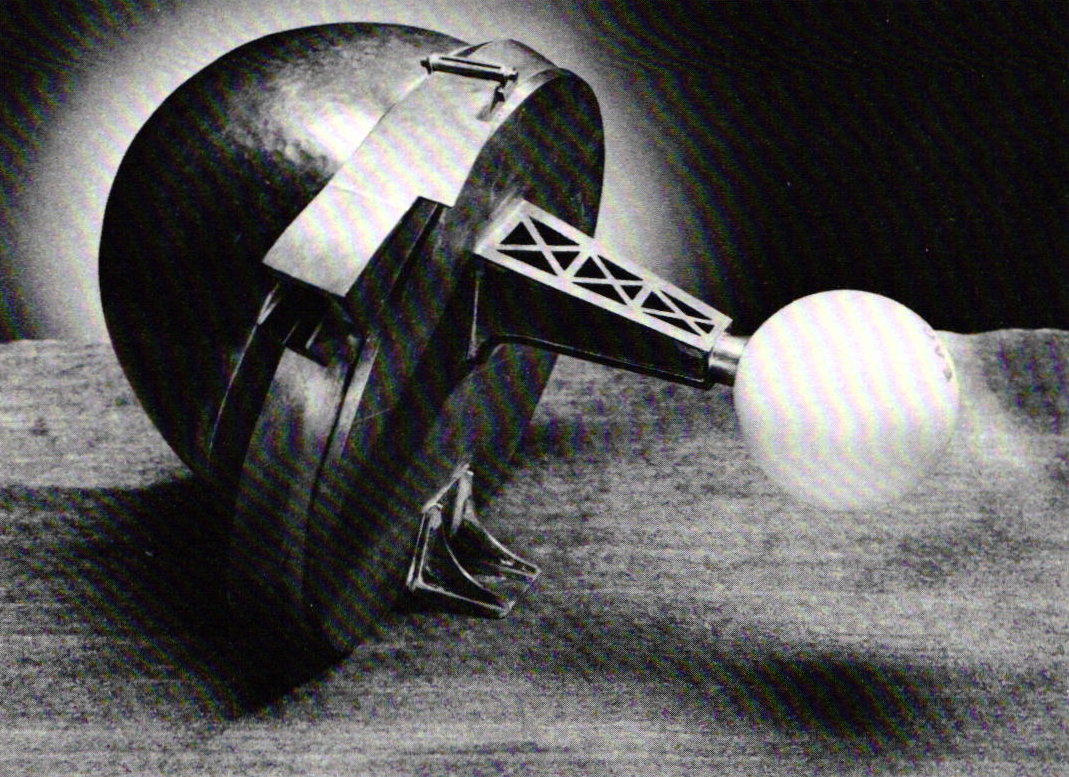

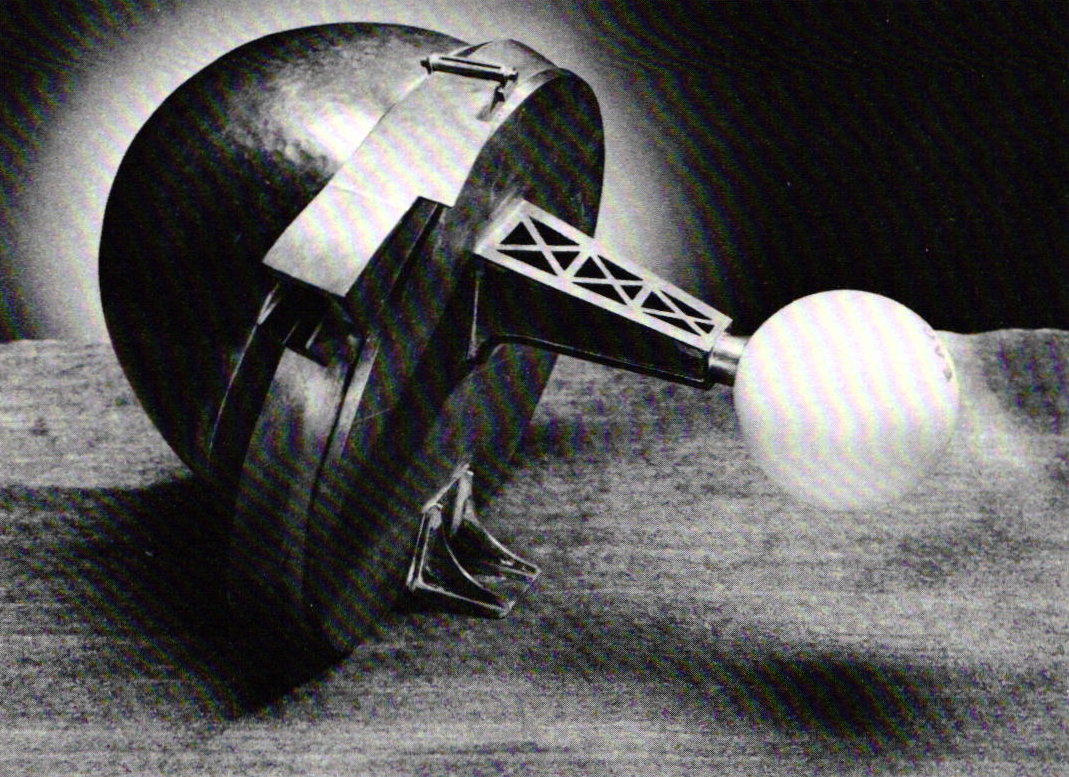

This show chronicles a year of transition in LaFollette's holloware. It begins with somewhat traditional geometric teapots, progresses through a macabre series of Euthanasia cups and ends with miniaturized teapot forms that are deconstructed, architectonic and combined with actual industrial objects. Throughout his work, we see a balancing act calculated to keep us in a state of anxious uncertainty. This is apparent when he is having fun with a teapot handle versus a teapot body in the early work, as well as when he later juxtaposes architectural, organic and found objects (i.e. a Briggs muffler and a field hockey ball) in the potent industrial teapots. It is clear that he is interested in exploring larger issues, but he is also dedicated to the teapot with its implied ceremonies that give weight to the artistic concerns. While the teapot itself gets deconstructed as his work progresses, it always retains a sense of real function (one does want to pick up and pour with it).

The 1988 sterling silver teapot that doesn't breach established conventions is an elegant example of applied geometry without extraneous design elements. The spout and lid contribute to a nice balance between the hammered-finish silver body and the bloodwood and silver handle that frames the pot.

The exquisite mushroom container produced near the end of LaFollette's Euthanasia series holds a fascinating irony. We know the shapes and colors foretell doom. They are all there; but though it is a straightforward metaphor for the atom bomb, it is ironically an esthetic container. A low, hooded, cone-shaped main body has a fat, purple-red patina; the color is neither cool nor warm. The highly polished cover rises from the base into a mushroom shape; copper at the bottom, it rises to silver and brass, married metal at the top. It is this married metal combination that suggests white heat. The effect is arresting. What makes the irony work is LaFollette's restrained narrative against a strong container esthetic. We are struck by its beauty and horrified by its subject. He has created a perfect metaphor for our fascination with the power of the bomb and simultaneous horror of its destructive power. This schema of repelling/compelling also is apparent in the Euthanasia cups; vertebrae seem paradoxically tragic and beautiful as bases for the elegantly formed copper bowls. Other pieces in the Euthanasia series tip the balance toward the morbid and are clues to the strong ironic imagery in his later work.

The 1990 teapot with field hockey ball signals LaFollette's current direction. The teapot, at this point, has been deconstructed and transformed into an improvisation of disparate parts. Using the containment/growth/tension inherent in organic forms as the theme of the body, he applies a swirling line around the pot, ending in an industrially derived spout. One side of the pot is cut off and a miniature, mufflerlike, trussfragment attached. A field hockey ball - the teapot handle - attached to this strut acts as a compositional foil. The industrial effect is enhanced by the tarnished steel-wooled finish. LaFollette's witty improvisation the muffler and hockey ball assemblages adds a note of droll humor to the otherwise melancholy field of teapot forms in metalsmithing.

Daniel Jocz is a metalsmith/jeweler living in Boston.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Inventive Jewelry of Earl Pardon

Metalsmith ’88 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

The Jewelry of Gijs Bakker

Randy Long: Works in Metal

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.