Metalsmith ’91 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

29 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1991 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Jan Brooks Loyd, Joy Pennick, Carolyn Morris Bach, Steven Brixner, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Material Culture Jan Brooks Loyd

Ariel Gallery, Atlanta, GA

March 1 - April 16, 1991

by David Butler

Throughout the 80s, Jan Brooks Loyd made lyrical, gestural vessels out of forged steel. These beautiful bowls were dealing with form, line, shape and other formal concerns. No less beautiful but certainly more mysterious is her most recent work shown at Ariel Gallery. The bowl has given way to the shovel and along the way she has added a strong political and moral message to these wooded sculptures. The handcarved linden shovels with roses, vines and other objects artfully burned into the wood, create visually arresting, thought-provoking objects.

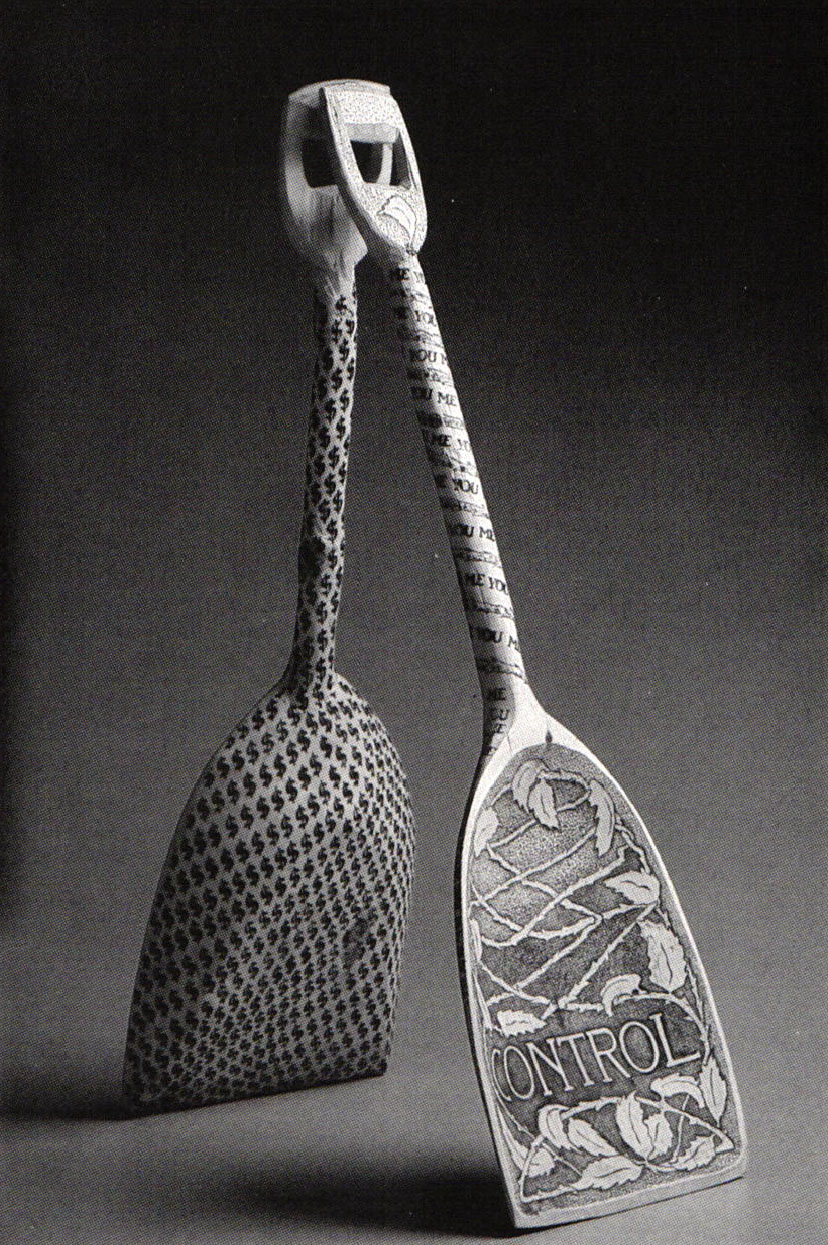

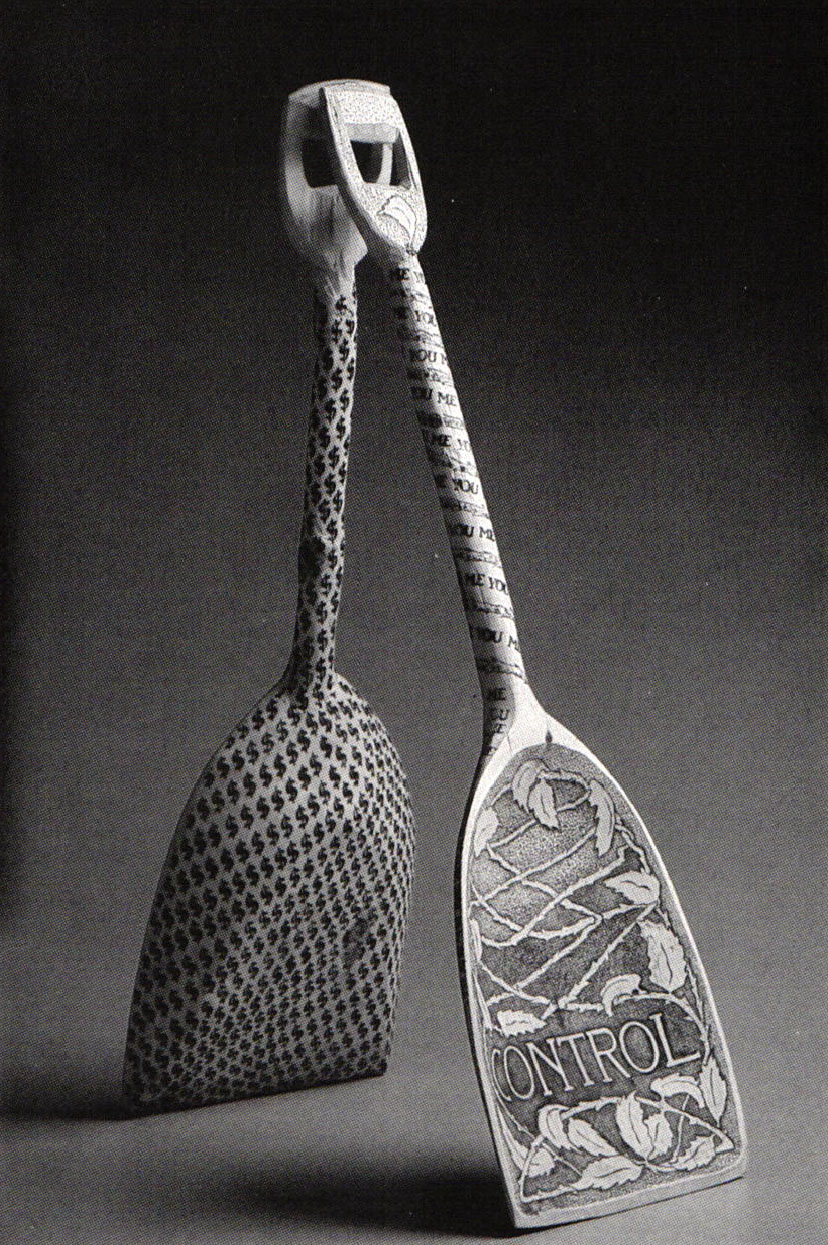

In Devices for Measuring Obscenity two shovels stand handle to handle, balancing each other in an upright position. On one shovel, the word greed is burned into the scoop. On the other shovel, control is burned into it. Loyd creates a statement on greed and that perhaps greed is control out of control. The message seems clear enough, yet why are shovels used as measuring devices of obscenity?

With the piece Devices for Mapping Cultural Nostalgia, the mysterious use of shovels continue. On one shovel, faithfully rendered roses rise behind the word "Faith." On the other shovel, two hands are reaching for a map-direction indicator. "Locus" has been burned into this scoop. Is the artist asking if faith is a nostalgic notion in the 90s? Does one really need a moral compass to guide one's life?

Why shovels? Shovels are associated with hard work, sweat, toil, construction and, of course, digging. I know that when mixing concrete, a shovel is perfect for measuring the right amount of sand to gravel, but is it an appropriate device to measure obscenity? Can one really use a shovel on an abstract idea like cultural nostalgia?

A third shovel sculpture gives us a glimpse that perhaps the artist recognizes her idiosyncratic tendency. In Taste Fracture, a wooden shovel has been covered with copper and brass foil. Interspersed among the metal sheets are newspaper and magazine clippings, almost collagelike. A meter stick balances this shovel in an upright position. Whereas her other works are very symmetrical, this one looks off balance, by any measure.

Perhaps keeping the viewer off balance is one of Jan Books Loyd's goals here. The sculptures are on the one hand visually accessible and on the other, conceptually enigmatic. There needs to be more resolution between the objects and the words on the objects. Despite the fact that I don't really understand these works, I like them, and I hope she will keep digging in this vein.

David Butler is a jeweler living in Atlanta.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Medium is Metal The Focus is Resources

Ashtons, Toronto, Ontario

May 4 - 25, 1991

by Susan Wakefield

The call for entries of the Metal Arts Guild's annual juried show stated "The focus is resources. your interpretation," and then, "We encourage you to submit whatever you are currently creating."

The show echoed this ambiguous premise. Size and scale of work were conservative but most pieces were technically well executed, some inspired. Resources were interpreted via recycled objects, reused material, such as rubber, records, nails, pine needles, leather, bark, wood, broken glass, broomstraws, coconut shell, tin cans and foil wrappings, as well as more conventional precious and nonprecious metals and stones. Often the theme was apparent only in the title.

Ann L. Lumsden's award-winning pin (the Steel Trophy Award - "Best in Show") made good use of design and material. In Case of Emergency and resembling a balloon with tail trailing, this pin was simple and elegant. The simplicity was belied upon closer inspection by a long list of materials and involved processes such as roller-embossing, engraving, plating, cast, sand-blasting and anodizing - not all of which are easily identifiable. The center of the "balloon" carries the message "O," under a watch crystal.

From Alberta came a charming piece with a somewhat ominous message in the title by Glenda Rowley. Whimsy and playfulness express themselves in a kaleidoscope of refracted light with constellations and weightless people floating around the handpiece. Balanced on its own stand of three springy legs on pointed feet, it is about to leap into space. Titled The Last Frontier it offers both challenge and threat - have we lost already?

Ene Kivilo of Ontario brought us back to earth with her four pins called Medals of Honor - Clear Rain, Pure Water, Green Forest, and Clean Air. Her forms are both geometric and naturalistic. The colors (black and silver) are clean and austere with abstract line images of inlaid silver in "ribbons" of black acrylic. The "medal" utilizies wave, mountain and cloud, while at the base are silver abstract "fringes" that symbolize hope.

This year's student award went to Joy Pennick of Nova Scotia for her four rings - circular with straight tops, or squared with inserted. The discs are either rosewood (Souvenir), slate (Foundations - Urban Resource), silver with copper overlay (Petrified - Wood) and reticulated silver (Mineral Rights - Aerial View). Someone was heard to say ("…..just when you think you have seen a ring done every way possible . . . " which expressed the general reaction to these rings. Clean in concept, fun to wear, they are delightful.

The show had a high level of workmanship and some excellent design but did not create a strong statement overall. Perhaps a stronger "call" would have pulled it together into a cohesive whole.

Susan Wakefield is a metalsmith practicing in Canada, who runs a company called AlumColor Plus.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carolyn Morris Bach

Sculpture to Wear, Los Angeles, CA

January 19 - February 15, 1991

by Carolyn Novin

Carolyn Morris Bach, in the manner of a shaman, uses her powers to amplify human awareness. While following basic processes and materials to make beautiful jewelry she doesn't produce work of pristine refinement; she eschews highly polished finishes and elaborately cut gems for surfaces that reflect exposure to time and wear. Silver and 18k gold are softly burnished, with bright highlights. Bach favors pearls and stones with intrinsic interest such as opal, tourmalinated quartz, Chinese writing stone and Japanese river rock.

Wrapping, typing, bezel-setting, looping, overlay - fabricating techniques are straightforward, obvious, and so gracefully achieved that they, along with metals and stones, are elements-vitale of each object. Considerable visual interest derives from varying line width, positive and negative space, gesture and movement.

Bacht forms are always organic, sometimes figurative, usually anthropomorphic. Asymmetrical units are joined in balanced composition. For example, in a particularly striking brooch, a smoothed Chinese writing stone and fabricated gold/silver pod - bead sustain a duet of complementary pattern and shape across a golden lattice.

In another brooch, a Tahitian pearl, carved bone figure and gold/silver tree recall sea-earth-sky linkage. As she uses these components, Bach preserves their characteristic qualities; she doesn't translate a leaf into metal but uses metal to make a leaflike shape. That each material retains its identity and joins harmoniously within an anthropomorphic object proclaims human reconciliation with all of nature - an important palliative for the alienating forces in contemporary life.

Bach's most recent jewelry refers to the ancient Greek story of Daphne who metamorphosed to escape Apollo s amorous pursuit. Tremendous energy meets terrific restraint at the moment of Daphne's transformation From nymph to laurel tree. Thrusting branches enclose the nymph, whose hair even flees skyward as leafing twigs. While they represent the desire to elude rather than actively to solve a problem, these brooches and necklaces also depict the moment where rebirth mandates loss of the familiar along with embrace of the new.

In this show of necklaces, brooches, earrings and sculpture, back designs economically, often using line, not form, and trusting simpler imagery to capture the defining essentials of her ideas. She continues to display an intense intimacy with her work and a unique sensitivity to combinations, compounding effects as she layers metals, as naturally as leaves spread upon a forest floor.

Carolyn Novin is a metalsmith and writer living in Los Angeles.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cathryn Vandenbrink

Concepts, Carmel, CA

October 5 - 31, 1990

By Dawn Nakanishi

Dynamic, sculptural, inventive are a few of the adjectives that would describe Vandenbrink's jewelry. Her work is based on the hollow double-ended spiculum. While many have utilized this form in making minimal jewelry, Vandenbrink has truly explored its decorative potential. She manipulates the curvature as a counterpoint to secondary hollow-tapered tubes. These sensual elements weave and "swim" together as if floating in space. The forms are usually in silver or a combination of silver and gold. The surface hint a hint of roller-printed texture and is given a matte finish.

Function has been carefully engineered into the design. All the spicula are very light and wearable. I would call her brooches "fibulae" because their pin stem is a composition element of the piece. The pin stem fastens the fibula by tuckins neatly into an overlapping seam. There are no unnecessary findings on the brooches and spare use of solder.

Her neckpieces, or more aptly "neck laces," are larger, plumper, double-ended spicula attached to a long, commercially made snake chain. They act somewhat like plumb bobs, one on each end of the chain. The necklace is designed to be tied by looping the snake chain. The loop can be positioned near or below the sternum on the wearer. The double-ended spicula fall at about waist level. The interaction of the spicula and the saucer change, depending on how the piece is tied. Wearers have the unusual freedom to choose how they wish to wear this neckpiece in a variety of compositions. These pieces have a pleasing sound as the metal elements gently move against each other on the body.

The simple forms, movement and sound are reminiscent of sculptures by Harry Bertoia and Alexander alder. I associate these works with interactive sculpture to wear, rather than pure adornment.

Vandenbrink makes two versions of this "neck lace" design. One is in silver with the brushed white-silver finish and the other in copper with a torch-colored black and earthy red magenta. Though both are the same design, the colors change the attitude of the pieces dramatically. The red and black strongly align themselves with organic and natural sensibilities. Their forms and earthy color suggest a primitive quality without crudeness. They also intimate a mysterious character absent from their silver counterparts.

In her copper "fibulae" (earrings and necklaces), wires move and act like black pine needles, and the snake chains are patinated black. The pieces hint at being talismanic or fetishlike without representational clichés. The fibulae consist of one double-ended speculum rather than two or three intertwined. They tend to be bolder and more powerful because of their size and color. They do not have the lyrical compositional feel of the silver and gold pieces.

Aside from pleasing form, the work has many other intriguing qualities: sound, movement, an unstructured flexibility and a delightful toylike quality. Earlier pieces had moving parts and intriguing qualities: sound, movement, an unstructured flexibility and a delightful toylike quality. Earlier pieces had moving parts and intriguing shapes to touch and rattle; so, from viewing the current works, it is clear that she is continuing a successful progression.

Dawn Nakanishi is an artist and instructor of Metal Arts and Jewelry at San Francisco State University San Francisco, California.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Steven Brixner

Gallery Eight, La Jolla, CA

May 4 - June 8, 1991

by Janice Keaffaber

Understated and elegant traditional shapes - circles, triangles, squares, rectangles and half-rounds - formed the basis of Steven Brixner's exhibition. The geometric forms of the 37 pieces were pushed to near mathematical precision, then transformed with a classical approach of softened angles and curved planes.

Surface treatments often include a subtle, file-textured finish, accenting the dense strength of the metal. Meticulously placed stones, rather than serving as a focal point, complete the esthetic. The inclusion of cubic zircon in many of the works adds a flash of light and increases the appearance of preciousness.

Multiple variations of "dangle earrings" use loosely hanging ripple-chains to connect two geometric elements and add movement. Brixner creates the individual parts and then puts them together into combinations of contrasting shapes. The top element is often a sterling or gold-plated sterling, circular disc. Attention is paid to the surface with texture or with the addition of tactile patterns of minute squares or triangles of gold. Smooth slices of stone, including agate, quartz crystal or red jasper, swing freely below.

Two necklaces emphasize the circle shape in distinctive variations. In one, file-textured silver discs alternate with carnelian twist beads, giving an interesting juxtaposition of color and surface. The other presents a more formal study of 14 large sterling circles, spaced with small, 14k-gold, solid, round links.

A set of lozenge pins" uses rectangles and squares, slightly curved with smoothly rounded corners. The gold-plated sterling has again been file-finished, creating a textured surround for faceted, clear-quartz stones, which are highlighted with sharp needles of tourmaline running through them in finely abstract linear patterns. The stones pierce the metal, adding light as an additional interplay in the composition.

The "paisley pin" series departs slightly from the geometric concept. Here the triangle form is coaxed into a graceful curve. In each piece, a cubic zircon rounds out the apex of the point, injecting balance into the design. Surface treatment varies. In some, 22k foil forms a gold-mosaic pattern across the piece, spaced to reveal precise glimpses of the underlying sterling. Other pins in the series incorporate multiple stones of garner, onyx, tourmaline, topaz or amethyst in restrained compositions.

The most successful brooch of this group uses a file-textured sterling background to emphasize the color of three tear-shaped turquoise stones. The shape of the stones, channel-set in 22k gold, relate to the outer curve of the piece and are offset by two small rounds of cubic zircon. Three additional brooches repeat the geometric embellishment seen in the earrings, with gold confettilike shapes sprinkled across the surface.

Brixner consistently references geometry either in actual form or surface treatment, giving a clean sculptural quality to the work. There is also a thoughtfulness of execution, with consideration to how pieces will feel and look on the body. This is jewelry designed to be worn.

Janice Keaffaber is a writer and enamelist living in San Diego.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Bruno Martinazzi

Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

October 11 - November 3, 1990

by Michael Dunas

Bruno Martinazzi, one of a number of post-war European artists who achieved prominence in both jewelry and sculpture, continues to work in both disciplines and to benefit from showing them together.

The stark, brooding anatomies, with which Martinazzi's work is often identified, first appeared in the 1960s. Using a timely Pop strategy, he isolated body parts to dramatize the human dimension of social issue. As though daily existence warranted a grotesque magnification to reveal the power of ordinary gestures, Martinazzi's clenched fist or accusatory finger was enlarged to sculptural icon, stunning in its sheer power of simple, direct body language. Likewise, his lip and belly brooches, diminished to the compact form of a fetish, had their own social magnitude as a symbol of the unconscious drive to project sexual power beyond physical intimacy.

In this show, which featured gold jewelry and tabletop marble sculpture from the last two decades. Martinazzi's strategy to render naked the relationship of social action with intimate feelings of love, hate and fear lost e great deal of its poignancy. Since the 60s, images of the body have become a battleground of socio-political agendas in art, coloring any subsequent figural representation with the blush of ideology. Martinazzi's precise, bloodless material handling of classic anatomies once appeared trenchant but now merely seemed locked into the past, oblivious to issues of homosexuality, gender, ethnicity, class, commodity, currently associated with this type of subject matter.

Regrettably, as much a result of the changing climate in art as the social context of jewelry, these brooches and sculptures elicited a feeling of passive idolatry, nude rather than disturbingly naked. Once incisive badges of raised conscience, they now seemed merely recondite jewels and precious memorabilia.

The works in this show that rekindled an appreciation of Martinazzi's analytical wit were the sculptural facsimiles of scientific instruments of the type used for calibration and measurement. In these, his accurate lines and virtuosity of craft match his minimalist style, with an appropriately detached subject matter. The metaphor is one of shallowness, placid still lifes of commonplace instruments that coldly measure the depth of human understanding. As disarming examples of Pop's melancholic side, these works maintain a critical distance from everyday concerns, holding in abeyance any vexing judgments of cause and effect.

The weights and measures, rendered with clear analysis, keen observation and the sure hand of material representation recast Martinazzi's role from alchemist and philosopher to stabilizing arbiter in a time of social confusion in art. And so, while his work in the past has been best described as a combination of the order of concepts and the chaos of sentiment, as the work of a scientific observer and impassioned advocate; for the time being, under current circumstances, the order of concepts has apparently prevailed.

Michael Dunas is a writer on craft and design.

A hard-cover, illustrated book Martinazzi with introduction by Paolo Fossati (in English) is available from Helen Drutt Gallery, 1721 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

David LaPlantz "Some New - Some Old Jewelry Metalsmithing"

Reese Bullen Gallery

Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA

March 6 - 23, 1991

by Kris Patzlaff

This comprehensive view of David LaPlantz's work from 1968 to the present included over 200 pieces, giving the viewer an insight into the work's technical and conceptual evolution. Containers, vessels and banks, constructed of brass and copper (1968-1978) were tucked away in deep shadow boxes. Tarnished and worn like artifacts or antiquities from the artist's attic, they reflected LaPlantz's statement: "I do not put much stock in what has happened, but rather what is happening today and the promise of tomorrow."

Similarly presented were a series of banks constructed with coconut shells as the primary forms (1977-1980). Their black crinkle paint created a rich surface, which LaPlantz embellished with black grosgrain ribbon, folded and tacked with black nails and chain mail. These banks foreshadowed LaPlantz's use of armor, which became a constant thread throughout his work.

In the earlier years armor was used as a means of embellishment and construction, but later, it became a personal vision for the future as well as a metaphor for protection. Large, angular hair pieces, with long knitting needles as picks, had sharp edges hinting at weapons. Spike Brooch (1990), with protruding earring posts as elements, decisively kept huggers at a distance. Stxyc's Mash (1990), and Slimline Facial Gear (1990), suggested an interest in futuristic armor; masks for protection against harmful elements in our threatened environment.

Another form of protection was evident in the 150 brooches, displayed in a gridlike fashion within three large wall cases. These all were badges or insignias determining hierarchy within a social organization (they also reflected LaPlantz's philosophy of making "a piece a day"). New American Smart Bomb (1991) is a fabricated circle brooch of painted aluminum with a small section of blue at the top right side. The remainder of the circle has red and white stripes. Two of the white stripes hold a cylindrical piece of wood with a string emerging from each end, reminiscent of a stick of dynamite with two fuses. Lighting the second of the fuses is sure to cause this "bomb" to blow up in the igniter's face.

The major transition exposed here was the introduction of painted aluminum in 1980 and anodized aluminum in 1984. Aluminum allows LaPlantz to work spontaneously and quickly, exploring primarily a two-dimensional surface. Engraved, scribed lines and pierced layers of colored aluminum expose underlying colors, layers or other materials. Line is often used in perspective, creating optical illusions that imply three dimensions. More importantly, aluminum provides color, an element sparsely touched on previously.

Pieces from 1980 to 1986 are testimony to the intensity with which he explored color; they range from saturated and bold to translucent and soft. Works using narrow fields of color provided by painted aluminum have limited success. Lacking richness, range of hues and depth, many feel static compared to works incorporating anodized aluminum. LaPlantz capitalizes on the colors of anodized aluminum by taking advantage of its futuristic appeal within hard-edge, clean-line and graphic images. He also explores its unlikely use within organic shapes and forged surfaces, pushing it to function outside its most obvious composition.

At times, the artist seems to use colors contrary to the intent of the work. For example, Hopi Influence Mask (1990) is a futuristic eye shield, primarily constructed of green aluminum. The historical reference implies ceremonial power or protection, neither of which are enhanced by this choice of color. Rather, this green is associated with a feeling of passivity and complacency. Although most of LaPlantz's pieces are not pioneering in the use of color, he exhibits a commitment to understand its potential voice and power.

LaPlantz's resourcefulness is reflected in his use of readily available shapes, from industrial extruded aluminum and knitting needles to found objects from the hardware store or Radio Shack. At times, these materials do not surpass their original intent, but more often, LaPlantz elevates pieces of colored electrical wire, plastic reflectors or an obscure piece of hardware to the status reserved for gems and precious metals. In Electric Company Brooch (1989), a piece of circuit board is as striking as a piece of mokumé gane and much more appropriate.

One might question the inclusion of some pieces in this exhibition, due to the implication that they are all "monumental" or "great." Overall, the range did provide an honest and intimate account of transitions and developing ideas. This was a straightforward and unpretentious retrospective, much like the artist himself.

Kris Patzlaff is a jewelry artist and teacher living in Trinidad, CA.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Historical Sources, New Visions in Contemporary Metalsmithing

Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY

March 1 - April 7, 1991

by Ron Netsky

In metalsmithing, just as in other artistic media, work of the past plays an important role in the work of the present. Whether consciously or unconsciously, artists draw on previous work to enrich their technical and conceptual vocabulary. "Historical Sources, New Visions in Contemporary Metalsmithing" examined the importance of antecedents in a show of impressive quality. The exhibition, curated by Lynn Duggan, showcased the work of six metal artists. Alongside the work of each of the artists was a reproduction of a historical precursor, along with a cogent explanation of the relationship of past to present work.

The most unusual approach to metal in the exhibition was that of Tamiko Ferguson from New York City. Ferguson doesn't fabricate or solder nor use precious metals. Her material: safety pins; her technique: linking. But viewers would be wrong to assume that Ferguson's concepts are derived in any way from Duchamp's ready-mades or found-object sculpture. The origins can be found in chain mail in which iron or mild steel rings were linked together (Four links through every one), and other garments from the 15th century. Ferguson's three pieces on display effectively showcased the breadth of possibilities of a medium most of us would not imagine beyond diaper-fastening. The most arresting of her pieces was Black Sphere, a seemingly infinite network of linked forms flowing endlessly into its core, while light catches the edges of the pins closest to the surface. Black Sphere conjured up a host of associations from the planetary to the microscopic, from natural sagebrush to man-made barbed wire.

Lucinda Brogden, from Rochester, updated the ancient technique of repoussé. While the method remains true to the 12th-century detail from a reliquary casket, reproduced here as an example, Brogden's subject matter is imbued with a lively, new wave, contemporary and surrealistic sensibility. In works such as Telesedation, They're so much easier since the VCR, metal is hammered into a wonderfully distorted view of bringing up children in the age of television. An armchair, floor lamp and television are far more animated than the children who crouch and sit before the screen, their heads having turned to televisions.

Johan Rhodes Update to 1989, by William Baran-Mickle from Rochester, goes beyond influence or historical precedent to the territory of satirical comment. The piece looked as if it began its esthetic life as a virtual copy of Johan Rhodes' Silver Pitcher of 1925, which is emblematic of pure-form Danish holloware. But Baran-Mickle has slashed the piece, inscribed it, added decorative squiggles to its surface and constructed a decidedly postmodern base and frame for his version. In adding this everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to a symbol of purity, Baran-Mickle comments wryly on moving-target aspects of esthetic standards in the 20th century.

Humor was also an important ingredient in New York Debutantes, garmetlike creations of aluminum, plastic, steel wire, glass and beads by Debra Chase, from New York City who seems to enjoy ridiculing the societal roles of the well-to-do. In each case a figure, dressed in the height of casual fashion, is suspended inside intricately crafted, wire-mesh, formal gowns.

All of the accoutrements of the debutantes' lives - hairbrushes, mirrors, pocketbooks - float around the bodice and hem of the garments. If not for this exhibition it is doubtful that one would connect the works to an Egyptian bead-net dress 4,500 years old.

The work of Christopher Ellison, from Rochester, is formed and soldered employing traditional metalsmithing techniques. But the manner in which he pieces together the metal is more closely linked to techniques of basketry (here the examples are Japanese baskets). All of Ellison's pieces on display juxtaposed a copper green-blue patina on the lower, wider-banded sections with a rusted texture and color on the upper, more intricate sections.

The delicate forms of Mark Stanitz, from Rochester, are compared to the turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau pendant by René Lalique. In works like Gold Spider, combining gold, sterling, enamel and rhodochrosite, one could see a kinship in the tasteful use of diverse materials, organic shape and negative space.

Melisa Chang, from New York City uses such modern techniques as electroforming to create paper-thin cups and vessels. In this case the works were compared not to other metalworks but to a raku tea bowl from the early Edo period. American Indian baskets were mentioned as another source of inspiration and it is to these that Chang is indebted for her bold pattern work on the vessels.

Ron Netsky chairs the art department at Nazareth College and is art critic for the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Society of North American Goldsmith Annual Conference

March 20 - 24, 1991

Atlanta, GA

by Keith A. Lewis

As always, the yearly conference of the Society of North American Goldsmiths (SNAG) demonstrated the profound and seemingly inescapable schizophrenia that lies at the heart of American metalsmithing. Faced with two poorly defined, but universally recognized paradigms: craft as art and craft as… well, craft, metalsmiths either carelessly pick sides or try to ignore the whole thing, hoping it will go away. Neither, of course, is a solution; and since so little serious thought is being addressed to the problem, a synthesis and understanding of the multiple goals that jewelry and metal can address remains always on the horizon.

Ostensibly, a professional conference should be an opportunity to present research, information and images and to engage in a healthy criticality. It should not be simply an opportunity to see friends, exchange tech-tips and receive each and every presentation with benign approval.

Numerous exhibitions and gallery tours were held in conjunction with the conference. These included the current Fortunoff Silver Show, at the new Atlanta International Museum of Art and Design, which showcased a number of exciting new works, as well as a few clunkers from the old guard, and an impressive show of William Harper's recent "Talismans for Our Time" at ArtSpace.

The talks, however, were more spotty than the shows and their varied quality was complicated by a lack of thematic unity in the topics. Several talks presented solid technical information, including a discussion of Dynalith EPR 5000 photoresist by Patricia Nelson and studio safety by Dr. Michael McCann. While generally informative, Dr. McCann's talk suffered from both excessive length and lack of specific information about hazards particular to metalsmithing.

A solidly researched presentation by Dr. Wolf Rudolph of Indiana University on "The Certomlyk Master" attempted to establish the hand of a specific metalsmith in several extraordinary objects produced in the Ukraine during the fourth century B.C. (see page 30 in this issue). In painful contrast, Dr. Duke Williams's discussion of "Contemporary West African Jewelry" turned out to be a rambling presentation of his own drawings and designs rather than an overview or study of the jewelry of that area.

Collection advisor Rosanne Raab gave an informative and thought-provoking presentation on the current status of collecting in the metals field. Her discouraging assessment of museum and collector interest was tempered by several interesting suggestions, including the possibility of a centralized national lending collection. A great disappointment was the cancellation of a discussion that was to have been conducted by Jan Brooks Loyd on the "possibilities that critical theory offers the crafts." This is the kind of assessment and challenge that our anemic and self-referential field desperately needs.

One of the great excitements of a SNAG conference is the opportunity to see and hear the heroes of the field, and at this year's conference three of them were asked to speak: Fred Fenster, Alma Eikerman and Albert Paley. All three, in their individual ways, have made invaluable contributions to the field.

Fenster, in a graceful blend of technical information and anecdote, presented a wide variety of pewter work, both his own and that of others. He managed to communicate a profound love of craft and material, and quietly and indirectly made a strong argument for traditional manifestations of craft.

Equally graceful was Alma Eikerman's long-awaited overview of her career as a teacher and metalsmith. One of the key figures in the postwar revival of American metalsmithing, Eikerman is known as an inspirational and dedicated teacher. She spoke of her studies in New York in the 30s and 40s where artists were "no longer bound to imitate nature" and were inventing "new ways to interpret visual reality." This commitment to ideological modernism was also demonstrated by slides of a remarkable body of work, spanning over 40 years. Despite its refutation by many current scholars, modernist theory still has enormous influence in the metals field, and a study of Eikerman's work and thought would contribute greatly to an understanding of its role. Her talk was given a warm and well-deserved standing ovation.

Impressive also was Albert Paley. Pushing past the size limits of jewelry early in his career, he took up blacksmithing. The attendant increase in scope has allowed him to produce large exuberant public works, which are unabashedly decorative, and based in form and gesture rather than ideology. Constantly expanding his technical range, Paley has managed to become enormously successful while maintaining integrity and honesty to his own vision. His talk, modest and thoughtful, discussed stylistic evolution, the search for "organic logic" and the use of ornament to enrich and explain structure. He spoke of the need to present oneself with daunting problems and to "make work a vehicle against the self."

In contrast, not the least bit modest was the talk by Robert Lee Morris. For some years it has been fashionable to cast Morris as the prodigal son and the great hope for the future of metalsmithing - ignoring the lack of quality and the derivative nature of most of his work. In his work, cultural expropriation, calculated "newness" and pseudosophistication place him well within the sexist, manipulative fashion world - a world that cares little for the meaning of craft. To my mind, looking to Morris for inspiration is a lot like high-diving into a birdbath: the shallowness gets in the way.

Are we so hard-up for heroes that we must flock to the adoration of someone who began his talk by telling us his income and ended it by advising us to make happy jewelry for the fall because we'll need "cheering up" after the Gulf War? In a dense and contradictory mix of five-and, dime zen, self-adulation ("my empire") and crass exploitation ("I'm always looking for the next angle"), he managed to elevate manipulation and hyperbole to new heights.

The revisionists look for excuses to admire him: "He paved the way for big jewelry"; and I ask, what about 1930s Bakelite, and our own Mary Lee Hu, Marv Ann Scherr and Arline Fisch? "He has gotten exposure for a lot of metalsmiths"; well, sure he has, but isn't a photo in Elle or Vogue a rather Faustian bargain? "He's shown it's possible to be successful, to make a living"; OK, so what about people who have kept their integrity and creativity and still been moderately successful, people such as Michael Good, Carrie Adell or Jan Yager, who seem to me to be production jewelers more worthy of our emulation and respect.

Morris spoke of being an "antenna of society," but we don't need antennas, we need beacons. We need people who embrace the exceptional, not the mediocre. We need people who aspire to quality and innovation, not to the almighty dollar. Morris is one tiny tin god whom we shouldn't bow to and whom we won't get respect for embracing. The standing ovation given him at the conference was an insult to metalsmithing, to notions of craft and of art and to the real heroes of our field who spoke before him.

Keith A. Lewis is a metalsmith, chemist and Gay/AIDS activist living in Ravenna, OH.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Jewelry of Cynthia Eid

The Work of Ivy Solomon

Galleries: Galerie RA

Laurie Hall: A Primitive Contemporary

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.