Metalsmith ’91 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

32 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1991 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features William Baran-Mickle, Joan Parcher, Philip Sajet, Peter Chang, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

William Baran-Mickle

Arnot Art Museum, Elmira, NY

September - October, 1990

by Ron Netsky

AII of William Baran-Mickle's pieces comment in some way on the forces of nature. In these works, he displays not only a concern for the environment but also a consideration of human beings' place in the greater scheme of things. The pieces on display range from literal interpretations of natural forms to more conceptual works. Even the most representational pieces go far beyond mere mimesis and, refreshingly, Baran- Mickle's conceptual works are not at all inaccessible.

River: Cadence employs a striking combination of brass, bronze, nickel silver and sterling silver in an evocative sculpture of a waterfall. It is not complexity of form that makes this piece so arresting, since the work is surprisingly austere. The form itself manages to effectively convey the undulations of earth, rock and water. Not the least of its interesting aspects is the manner in which the piece turns from flowing horizontal to more turbulent vertical in a manner that suggests a bent human torso. When we see the reflective surface of these waterfalls and the textures of the rock cores, we must, at least subconsciously, consider the earth's pockets of metals and the minerals suspended in water. We know the works are scaled representations, but the fact that they are composed of metals rather than wood, or even clay, makes for a more immediate relationship of material to content.

Continental Drift is perhaps the most complex manifestation of Baran-Mickle's theme combining associations of navigational instruments: an exploded world globe, the hull, masts and sails of a vessel and petroglyphs from all corners of the globe. While the sail shapes seem to be indicative of the drifting continents, the petroglyphs signify a unity of human culture that metaphorically brings together the land masses that separated eons ago. All of the above elements are balanced over a purposefully crude, painted ocean of waves. The result conjures up visions of a world out of balance and adrift despite, or because of, the progress of humans.

In his artist's statement, Baran-Mickle says his recent focus has been a dual image unified by an overriding form. Canyon Song contains a tension that takes Baran-Mickle's concept a step farther. Here, there is a clear implication of two halves of a structure that was once whole. The V-shaped outer form seemingly remains standing only because of a series of rods that span its length, preventing it from toppling. The smooth, fluid exterior is effectively contrasted by the combination of the three oxidized metals that form a rough, disturbed surface in the center. In Overlook, the chasm is between two nude bodies, a male and female, both headless. What can be seen as the overriding form here is a bricklike - therefore manmade - structure partially surrounding the figures, which contours to the bodies as perfectly as the organic materials that seem to be oozing between them. The piece can be interpreted as an exploration of constructions of civilization encroaching upon and limiting the more natural aspects of human relationships.

Ron Netsky chairs the Art Department at Nazareth College and is art critic for the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Joan Parcher

Rezac Gallery, Chicago, IL

September 7 - October 6, 1990

by Myra Mimlitsch Gray

Joan Parcher's work is modest in scale, materials and technique, yet intellectually rich, humorous and beautiful. The pieces raise questions about the function of jewelry and the value of materials and processes. Her construction techniques are not pretentious but direct and practical methods for conveying ideas - the real strength of the work.

The show exhibits various levels of commitment to the content and to the esthetics of jewelry. There is a chain fabricated from thin mica disks that celebrates the pure beauty of the material and simultaneously plays off the irony of creating a chain of weak links. In another group of mica pieces, Parcher imbeds chips into simply constructed marquis-shaped bezels. When the form is oriented on the body horizontally as a brooch, it is transformed into an eye, peering out at the viewer. In another instance, Parcher hangs the same form vertically from cable as a pendant; in losing the eye reference, the piece becomes more formal and less interesting.

Parcher uses exaggerated shifts in scale to make a humorous pair of earrings that comments on commercial jewelry forms. She enlarges the commercial screwback finding so that the form, usually a subordinate aspect of the design, becomes the entire earring. The result is a playful parody of industrial esthetics as well as an homage to the handmade. While this is an amusing idea, it seems limited to a jeweler's inside cliché.

Other works in the exhibit were more conceptually sound. Hanging on the wall were two neckpieces with pendants that are large, dark, sensuous forms, wishing to be held and felt. Black streaks on the wall revealed that the forms were carved from solid graphite. This realization evokes both delight and horror. The pieces beg to be worn, yet defy the probability by virtue of the implied consequence - the ultimate smudging of one's clothes and the inevitable disintegration of the piece. These pieces toy with our desire to adorn ourselves while scorning our preference for preciousness and challenging the permanence of jewelry.

The work that offers the most poignant critique is a group of eight gold rings, arranged in a circle, that reads: "We Touch It But Do Not Find It." It's not just another diamond-studded bauble.

Myra Mimlitsch Gray is assistant professor of Metals and Jewelry at Purdue University in West Lafayette, IN.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Philip Sajet: Jewelry

Jewelerswerk Gallery, Washington, D.C.

September 27 - October 18, 1990

by Lenore D. Miller

The overall statement made by this show of 27 pieces was uniquely ominous, highlighting Sajet's hallmark - mystery. The experience of Sajet's pieces may be akin to the discovery of buried ceremonial treasures, like a golden horde. Such artifacts remain somewhat mysterious out of the larger context of their civilizations, yet can be admired intently for their iconic appeal.

A Dutch jeweler, born in 1953, Philip Sajet is the grandson of a Parisian jeweler who worked in the style of Van Cleef & Arpels. The influence of this heritage can be observed in an ongoing sensibility for meticulous craftsmanship and difficulty of execution that are evident in his best work. These vestiges of old-world influences have been assimilated into his experience as a craftsman and seem to have remained consciously embedded in his designs.

In his work that relies on solid geometry there is a certain purity of form, yet his preference for crystalline shapes, pyramids and hierarchical arrangements brings to mind the Byzantine period of decorative arts, characterized by its luxurious use of precious metals and encrustation of gems on gold. Light remained the primary vehicle for religious expression, and the use of the crystal in Sajet's pieces may perhaps stand for pure light, like the light of candles reflecting off precious metals and glass mosaics in Byzantine churches.

Mythology and personal iconography can be found in a piece such as the Ring of Democles, which has a point directed toward the wearer's finger. The Water Bracelet is another example where the design of the piece, an undulating blue enamel linked form, brings to mind both strength and fluidity. The fluid aspect of sajet's work is also expressed in the use of gold mesh links to create a collapsible ring.

The conceptual, almost narrative, side of Sajet's work was also expressed in the exhibition. Hanging on the wall during the exhibition was photographic documentation of an imaginary necklace, an arrangement of gemstones set out in a particular circular order and photographed. A similar circular arrangement created with common beach pebbles evoked a play on the idea of monumental sculpture, bringing to mind, with the absence of a frame of reference at this scale, other monumental ceremonial circles, such as Stonehenge in England and even the ceremonial mounds of Native Americans. Also, the use of natural stones suggests geology and the forces of change in the universe. Gemstones, likewise, reflect on the jeweler's domain and seem to echo the refrain between the beauty that the artist creates and the inexhaustible ability of nature to inspire art.

The artist promotes dualities in his ring forms. For example, some pieces were meant to be worn paired on the same hand. In one such pair, made respectively of silver and gold, one is pyramidal in structure, the other a trident shape in profile. One is tubular, the other square in section. Two other rings were particularly strong in design, complex and innovative in concept. The first is a gold ring band incorporating a gold mesh and seed pearl drum, which supports an unusual crystal. This ring is quite sculptural and spatially complex when compared to the mounted magnet ring. The matte finish and mechanical quality of that ring give it an other-worldly feeling, almost as if it were a relic or ritual object of an alien civilization, a civilization much more advanced or much more ancient than ours, and maybe not of this earth. This quality is achieved through deceptively simple means.

Part of Sajet's esthetic response to contemporary ornament is the juxtaposition of elegant and rough textures, angular and smooth surfaces. The ring that combines a magnet with tantalum, although not a new idea, seems fresh and timely in the context of this exhibition. It brings to mind the idea of the earth's magnetic poles and the larger issues of chance and design in the cosmos. Sajet's designs present a severe yet always elegant presence. As sculpture, they dance between an involvement with both minimalism and conceptual art. It is this tension between two poles of being, the decorative idea and its manifest form, that makes the pieces hard to describe but equally hard to forget.

Lenore Miller is an artist, lecturer and curator of art at The Dimock Gallery, Washington, D.C.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Peter Chang

Helen Drutt Gallery, New York City

September 11 - October 6, 1990

by Vanessa S. Lynn

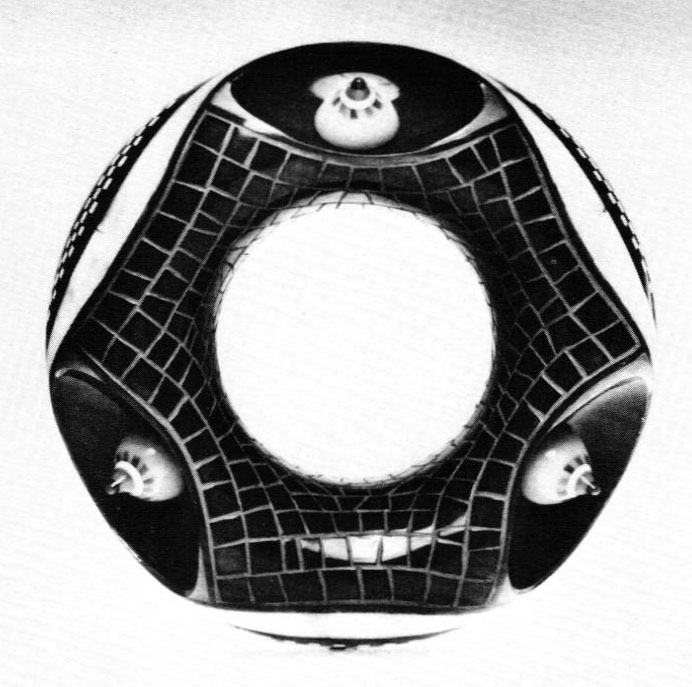

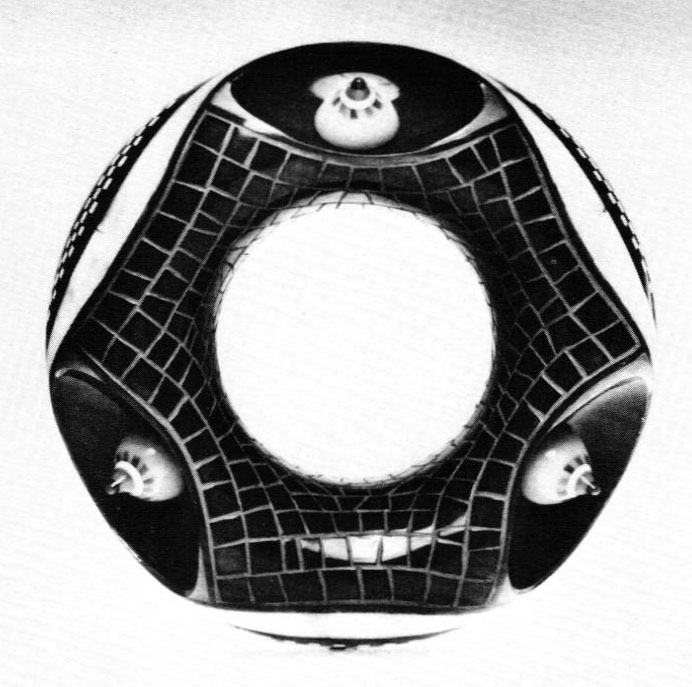

Peter Chang walks the tightrope of good taste. In his first solo show in New York, this London-born and educated artist, currently living in Scotland, presented 30 pieces - brooches, earrings end arm rings. They are constructed primarily of opaque, colored plastics, which are sometimes heat-formed, carved and/or lacquered, and often cut and inlaid. His bulbous, slug/bug brooches and outrageous, oversized arm rings have an exuberance that make them initially seem flighty, street-smart and ephemeral. They suggest "fashion fun" more than "serious jewelry." But a closer examination reveals their painstakingly meticulous fabrication. They bully and intimidate the viewer to reconsider their excessive esthetic.

It is in the arm rings that these ideas are best advanced. Over a lightweight, curvaceous, lathe-turned armature (up to 7″ in diameter), Chang constructs a tightly planned crazy quilt of rippling opaque colors and twisting patterns and textures. Small, red-and-white polyester, checkerboard tesserae abut a larger, black-on-black inlay with alternating "tiles" bearing raised, red-and-green crescents. International yellow, beveledged, diamond shapes are inlaid with small, red domes marking every tile juncture. Smaller, flat, diamond patterns in reds and blues are laid to permit exposure of the blue-tinted adhesive beneath. Chang makes PVC simulate snakeskin! The most recent work adds physical dimension to the already boisterous amalgam. Concave, ovoid windows are carved into the ring surface, with multicolored "jewels" set on center; polyester domes and cones erupt at regular intervals. The visual ambiguity created by dense pattern and color that fails to follow form is rendered even more baroque.

Many of the flat, geometric inlays suggest the Art Deco masterpieces of Raymond Templier or Jean Dunand. Amazingly, the dynamism of the Art Deco work pales beside Chang's orchestration. The rich diversity that marked the best of early Bakelite jewelry is also recalled. While Change resembles neither, he references both. Quintessential jewel turned into quality kitsch - high culture meets low. These pieces have the irreverent exuberance and playfulness of a Niki de Saint-Phalle; Chang's jewelry does for the body what she does for the landscape. The artist's vision is an intrusion on the site, a biomorphic, color-crazed assault that opposes its host and demands both attention and acknowledgement. It's no accident that his work has accessorized the fashion collections of Rifat Ozbek. He seems the "bad boy," the psychedelic Christian LaCroix of European jewelry. His topsy-turvy allusions are equally unlikely and equally far flung - Ravenna mosaics and pin-ball machines, Hagia Sophia and crackerjack rings, Gaudi and customized California cars, bowling balls and sci-fi aliens, drawn with a cartoonist's nib.

Peter Chang teeters between fashion and art. The bold use of color and pattern are the decorative concerns of the former. His excessive scale, technical brilliance and message signal something more. That message is the unpopular one of humor. Chang is serious about "serious fun" - jewelry that makes the participant smile, even laugh. He may be unique in rejecting narrative to achieve this aim. No cartoon characters or "kitchen cuties" here. Instead, he imbues his manipulations of color, surface and mass with a riot of cultural associations. His choices succeed in returning "joy" to jewelry.

Vanessa S. Lynn is a writer living in New York.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Silver: New Forms and Expressions II

Fortunoff, New York City

October 1 - 21, 1990

by Janet Koplos

The "celebratory nature of silver" is a felicitous phrase for this second Fortunoff "New Forms and Expressions" silver competition. Offered as a theme by jurors David McFadden, Ronald Pearson and Helen Shirk, the concept of celebration encompasses both the luxuriousness of the silver material and the fancifulness of the forms invented by contemporary metalsmiths.

Without such a label, one can only speak vaguely of the range of the group show, lament the absence of label distinctions between competitive and invited works and acknowledge the continuing sharp divisions between the modernist objects that put service first and the contemporary objects that put originality and expressiveness first. Having invited works is a copout, because the exhibition is billed as a competition and because invited works may be older pieces that blur the sense of "what's happening now." It's more interesting to concentrate on the competitive pieces, noticing the absence of high polish. Ninety-five percent of them would fall in one or another of three formal themes: totemic, architectonic or animalistic. By means of the catalog, because it separates juried and invited entries, I discovered that the juried works by themselves would have been a fine, balanced, interesting show - only rather small, at 16 items.

This year's first place winner, the Tuscany teapot by Randy J. Long, was shown in Fortunoff's Fifth Avenue windows, but other prize-winners - Boris Bally's ambiguous emblem-object called Kalimba, Kevin Costello's bowl, nonfunctional aperch its copper scaffolding, called Cradle and Foundation: self-sustainment and Vernon Theiss's industrial engine masquerading as a teapot - were shown at the back of the first floor and were easily missed. The bulk of the show was on the top floor.

This "juried show" comes with solidly functional items that also are interesting to study: Sue Amendolara's Egyptian-inspired scent bottle, oversize napkin rings by Karin Bockenhauer in fragmented spirals that are more constructivist than organic, the origami/erector set candleholders by Margaret Boor, Robert Farrell's confetti-dashed dessert servers (perhaps they look a little more like gardening tools), Robly Glover's dachsundish tea server and Yosuke Inoue's penguinish pitcher.

So-im Kim's Vessel XI, like Randy Long's first-prize teapot, is more an interesting accumulation of parts than a unitary whole. Kim's pot is as sharply faceted as a slate quarry, while Long's assemblage of marble pillar, sun disk and silver cypress tree - ostensibly the handle and lid knob - makes a surreal landscape.

Debra Stoner's untitled vessel, given an honorable mention, might have been a perfect blend of art and function (as an elegant, fringed, footed fruit dish) except that she tipped it toward art by scattering tiny metal beads across the bowl. Gina Westergard's Eternity teapot is another that favors expressive form - and how sinuously, erotically, the almost dematerialized lucite handle coils around the cool contours of the silver pot.

Strangely, it's only among the invited entries that one sees virtuous conceits, the most egregious of which is Robert Ebendorf's pedestal platter pimpled with mounted pebbles and bottle glass. Mostly the invited works are classic forms (Heikki Seppä's spiraling Object in Silver, or elaborately worked out static images (Linda Threadgill's miniaturized architectural trophy). The show would have made more of a statement without them.

Janet Koplos writes frequently about three-dimensional objects.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thomas Mann: New Work

Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, MA

October 6 - November 2, 1990

by Anne Crowley Tom

Thomas Mann's recent work on view at Mobilia Gallery in Cambridge strongly reflects the influences of early 20th-century modern art. The range of work represents Mann's new direction as a designer and sculptor, described by the artist as "experimental," and inclined towards larger-scale, wearable and nonwearable pieces.

Reminiscent of Russian Constructivist and assemblage art are three one-of-a-kind necklaces, miniature sculpture-boxes that reflect Mann's role not only as a jeweler and metalsmith but as a major force in the 20th-century craft movement as it relates to 20th-century art. Like Joseph Cornell's boxes, which often reflected a romantic fascination for science in post-Victorian America, they contain an assortment of small products of technology. One of these necklaces, inscribed with the title War Odds, with its focus on geometry and the interplay of forms, recalls Alexander Rodchenko's constructions. Mann, who states that his works "always tell a story" but "form takes precedence" in his selection of subject matter, has isolated manmade shapes of plastic toys and found objects in the quadrants of a squat triangular box of sterling silver.

Like contemporary metalsmith Anton Cepka who, in Mann's words, "breaks trust with the concept of precious metals," Mann relies upon design to achieve his artistic solutions, using silver, bronze and nickel in combination with found materials. In the upper left-hand quadrant are dice fabricated from micarta, which the artist uses as a substitute for ivory. The upper right cell holds three stainless steel balls, while in the lower right are twists of iron wire giving the impression of barbed wire. The left cell contains objects resembling bullets, repeating the bullet shape of the dangle composed of bronze, copper and silver, hanging from the bottom of the box. On top of the box sits a miniature cast-in-bronze Babylonian warrior in front of what appears to be a horizontal barrier from a miniature train set. Each subdivision separately and in relation to the whole prompts political narrative in form, color and texture.

Another important new medium for Mann is furniture, which is represented here by a side chair constructed from the same range of metals, manmade materials and found objects used in his other sculpture. His new furniture is exemplary of "Techno-Romantic," the name Mann coined for his style of juxtaposing modern technological processes and materials (such as color xerography, new techniques in photography, contemporary found and fabricated objects) with classic romantic imagery. In this piece, Mann contrasts dreamlike, narrative subject matter with the materials of this generation. The sketch from which he worked on the chair (exhibited with it) indicates the range of technologically influenced processes involved in its construction. From it, we see how surface design is created with space-age materials: electrical tape, copper foil, eight-gauge aluminum wire wrapped around the front legs, binding wire on the base structure. With arms of ¼" perforated aluminum, a back of plexiglass slab, and under the plexiglass scat a clock collage that evokes Kurt Schwitters's assemblages with surreal imagery from the earliest part of the century, this piece embodies the Techno-Romantic style grown to new dimensions.

Anne Crowley Tom is a freelance writer based in Manhattan. An art historian and former director of education for the California Museum of Science and Industry, she has a particular interest in the relationship between art and technology.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Robert Griffith The Belin Works

Marywood College Contemporary Gallery, Scranton, PA

December, 1990

by Matt Povse and Sandra Ward

Robert Griffith's new body of work, made in the last year under a grant from the F. Lammot Belin Arts Scholarship Foundation, is a collage of color, line, form and materials, amalgamated with adventurous metalworking techniques and carefree storytelling. The unconventional surface treatments make the metal fabrication enigmatic. To realize that they are not wood, cast paper or clay, for example, commands a respect for Griffith's technical prowess and an appreciation for his audacity towards the material itself.

At times, the color is strong and penetrating, as in Caldron in which the patina is manipulated. In Faun and Sentinel Vessel, painterly color, achieved through paint sticks and prismacolor, is elusive and whispery, sparked by gold leaf. In Ancient Voyage, the colors of the raw metal are so well integrated with the greens and browns of the applied prismacolors that it is difficult to discern one area from the other.

Like the color, Griffith's lines are independently successful yet held together by the strong profiles of the various shapes that comprise the total image. These profiles are gestural and familiar and host the other symbiotic lines that may be naïve, humorous, mysterious. Line manifests itself as drawn prismacolor strokes; raised stick-arc lines depict trees, animals, scenes; wavy, wispy lines cut through the metal with a plasma-arc cutter; large, curved lines are fabricated onto other components of the sculpture; enamel paint has been applied to produce swirled, brushed lines. His line is never static. The composite use of various lines in each sculpture heightens the unpredictability.

The forms that are the vehicles for the line and color are mostly "stacked" volumes. They evoke images of pre-Columbian clay vessels (Ritual Vessel II), and the bronze ritual vessels of the Zhou Dynasty (Caldron). The spirit of chalices, ciboriums, reliquaries and other ceremonial/religious vessels, perhaps made from fine metals encrusted with jewels, is present. Primal images flicker across the mind as one associates Faun, Ritual Vessel I, Ancient Altar, Sentinel Vessel and Testimonial to cave paintings or shamanistic rituals. The totemlike shapes are reminiscent of Romanian grave markers, or possibly Brancusi. Such is the wide spectrum of Griffith's deliberate allusions.

This body of Griffith's work has evolved from jewelry/metalsmithing roots with its recognizable techniques and images, but the scale is different and unique. Here we have mysterious objects and symbols that could be carried by hand and placed on the table or altar, to ward off spirits or record certain events. Instead, Griffith's sculptures tower above us and confront us from an aggressive position of dominance.

Matt Povse is an instructor at Marywood College (Ceramics, 3-D Design) in Scranton, PA, where he also lives, and is former executive director of Peters Valley Craft Center.

Sandra Ward is assistant director of Peters Valley Craft Center, Layton, NJ, where she also lives, and was the textile resident for seven years.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Glorified Goblet

Signature Gallery, Boston, MA

July 1 - August 15, 1990

by Susan Barahal

Drinking vessels are ubiquitous objects. Their need is universal and they can be made in a variety of materials and multitude of shapes. Excavations have unearthed simple forms dating From the Stone Age, precious gold vessels from the Scythian civilization, sophisticated glasses from ancient Persia and Rome and narrative painted clay cups from ancient Greece.

Of all the forms that drinking vessels can take, the goblet is perhaps the most elegant. Goblets are distinguished from cups and glasses by their width and capacity. Historically, the large bowl portion had no handles and sat upon a stemmed foot. Some were elaborately decorated and their large size enabled the goblet to be passed among guests for drinking a toast in celebration. Often, the stem would be heavily carved in order to prevent the goblet from slipping through unsteady fingers. Today the term goblet is used loosely for any large drinking glass, although goblets are primarily reserved for celebrations and are usually associated with ceremony and festivity.

Signature Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts recently celebrated the goblet as an art form in an exhibition and competition entitled "The Glorified Goblet." More than 80 artists working in a wide variety of mediums submitted pieces of extraordinary diversity and ingenuity. Each artist created art forms that expressed a personal interpretation of the concept of goblet. Most striking was the number of entries that were entirely nonfunctional as goblets or, for that matter, as any kind of drinking vessel. Over half of the works were nonfunctional, and a number of those that could be used were impractical and problematic as vessels. Clearly, functionality was not a primary concern to the majority of the artists.

Not was functionality a concern of the judges. The goblet awarded "Best of Show" was a nonfunctional piece by Carolyn Morris Bach entitled Chalice for a Woodland God. Bach's choice and rendering of materials simultaneously convey feelings of primitivism and preciousness. The vessel form combines silver, copper and 18k gold, and includes a beach stone that has been polished to a high gloss and bezel-set like the finest cabochon ruby. The pouched-shaped vessel rests on an altar fabricated from forged and soldered wires, suggesting sticks that have been lashed in place. Sue Robert's goblet also sits atop an assembled structure. All elements are attached pieces of enameled sheet-metal and the form is an innovative variation of the traditional goblet - a bowl on a stemmed foot. Like the Bach piece, it functions as a free-standing sculpture, but Robert's vessel is whimsical, playful and amusing. The black-and-white markings are not meticulously painted but are, rather, executed in an intuitive and childlike manner reminiscent of Jean Dubuffet's decorated sculptures.

One is easily intrigued by Robert Stephan's blown-glass goblet. Stephan fuses multiple layers of precious metallic oxides to the surface of the glass, causing the surface to reflect varying wavelengths of light and, therefore, multiple colors. The result is what the artist refers to as dichroic (meaning two colors) glass, since one color becomes another when the light changes or the viewer moves. Colors and patterns continually shift, transforming the goblet into a hologram.

At first glance, Christine O'Leary's goblet, although tiny, appears to be utilitarian. However, it is so delicate that one is afraid to even touch it. The bowl portion is a gold-leaf eggshell that is attached to a Paper stemmed foot. Its fragility demands special treatment and communicates a sense of preciousness.

Since goblets are familiar objects usually reserved for special use, many of us have associations and identifications with these forms, recalling celebrations, rituals, milestones and transitions. The goblet becomes a symbol of these events and its symbolic role can be more significant than the vessel's potential functionality. In fact, the goblet that is not at all functional as a drinking vessel can perhaps be more powerful as a symbol of ritual than a goblet from which one can drink. Stripped of its utilitarian function, its purpose becomes entirely that of symbol and sculpture, allowing it to transcend the confines and limitations of definitions such as "drinking vessel." By creating objects that we think of as only serving a particular useful function and rendering them "useless," artists like those in the "Glorified Goblet" force us to pay attention to the object as symbol and form. We are obligated to rethink and reevaluate our preconceived ideas about familiar objects.

Susan Barahal is the decorative arts editor for Art New England and teaches art in the Boston area.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jewelries/Epiphanies

Artists Foundation, Boston, MA

September 4 - October 18, 1990

by Edward S. Cooke, Jr.

Jewelry has traditionally been defined in terms of decorative effect, precious materials and fashion, Design economics for necklaces, rings, pins and other bodily armatures have often been determined by wearability, appropriateness for use, precious metals and gems and time-consuming workmanship. In the 1920s, Modernists took the first steps in challenging the parameters of this traditional view. They sought to use commonplace materials and to work within a minimal philosophy that aspired to a timelessness that transcended style.

Although graduates of American art and design schools from the 1950s through much of the 1970s continued the time-honored notion of decorative jewelry in different styles, studio jewelers during the past decade have sought an alternative, ecumenical route. Instead of rejecting tradition, they have built upon the history of jewelry, including the exploration of the Modernists, to bring new energy to jewelry forms. Combining precious materials with minimal designs, using the materials as well as the forms to engage the wearer or viewer, exploring the relationship among weight, scale and materials, making narrative statements, or using the forms to explore new notions of function, contemporary jewelers have staked out new terrain.

"Jewelries/Epiphanies" demonstrated how far some jewelers have pushed the field. The concept for the exhibition took shape about two years ago when a group of Boston-area jewelers and metalsmiths shared their frustrations about the lack of opportunities to exhibit thoughtful or provocative work. Helen Drutt Gallery and Rezac Gallery showed such jewelry, but most galleries favored commercial work and displayed it crowded into horizontally oriented cases more appropriate for department stores. The Boston-area artists, led by Daniel Jocz, formed a group called MARS, an acronym for Metalsmith Arts Resource Society that also suggests a militancy about their commitment to thoughtful work. MARS presented an exhibition proposal to the Artist Foundation, but not until late 1989 was there interest. At that time Barbara Baker, the new director of the foundation, and Catherine Mayes, the curator, expressed an interest in the small sculptural work. They accepted the MARS proposal submitted by Jocz and Joe Wood and suggested that the exhibition include other artists. Linked by a common goal to present work that transcended sales restraints, that was jewelry for the mind and eve as well as the body, Jocz, Wood and Mayes developed an exhibition that expanded "the notion of jewelry beyond ideas of decoration" and presented it as "portable works of art."

The three curators picked 17 artists from New England and New York to participate. Each artist was represented by 10 objects. Taken together the work in the show documents several of the directions in studio jewelry and points out certain regional patterns. Many who work in New York have continued in the Modernist tradition. Eva Eisler's geometric stainless steel forms, joined with cold interlocking connection, are a contemporary expression of constructivism. Pavel Opocensky models his geometrically shaped pieces of Colorcore laminate to produce alluring brooches that posses a tactile richness. Using commonplace materials such as stainless steel and steel cable, Lisa Spiros constructs necklaces that challenge our perceptions of size and weight. The large hollow pendants are actually very light, an ambiguity that parallels the ambiguity in materials. A slightly different minimalism is evident in the work of RISD graduates. Didi Suydam and Sandra Enterline both employ precious materials to construct stylized forms or combinations of forms. The continued influence of Jack Prip is evident in the slightly abstract conceptualization of these pieces, as well as in the scratch finish. Joan Parcher, another Rhode Island jeweler, has taken this philosophy in a new, exciting direction by using graphite pendants, a heavier than expected element that leaves a mark on the wearer and shrinks irreversibly with use.

Of the Massachusetts artists, Susan Hamlet, Claire Sanford, Alan Burton Thompson and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman address issues of figure and narrative. For this exhibition, Hamlet submitted two series of flat brooches in which robotlike profiles were juxtaposed with different interior voids. In the "Four Seasons" series, she narrates a personal story, beginning with a fissure in the fall, which becomes a ghostly figure in the winter, a more humanlike figure in the spring and a young woman in the summer. Sanford, on the other hand, produced a series of brooches that became increasingly frail in body, but bright in small decorative detail near the top. The making of this series coincided with her brother's battle with AIDS. Combining found materials with precious materials and mounting them on carved basswood, Burton Thompson provides material vignettes that evoke past events or emotions and demand engagement. Slosburg-Ackerman uses asymmetrical pairs and triads of natural and fabricated forms to explore relationships of life and death, exterior and interior structure, time specificity and timelessness, natural and artificial. Joe Wood uses a less naturalistic language to address similar issues of temporal gradation and age. His constructions are sparse but not really minimal, with a fine sense of detailing and patination to reinforce the temporal and rhythmic concepts of his forms. Two artists pushed the boundaries of function. Boris Bally employs precious materials and elaborate techniques to create disturbingly dysfunctional or aggressive pieces. The resulting works possess considerable physical and conceptual tension. Dan Jocz's rings, plain geometric bases with colorful protuberances mounted on them, embody a whole new perspective on defining function. Their use is extremely limited: the rings are not really wearable, the fragile, fugitive paints will wear off over time, and the rings act more as pedestals. Nevertheless, like carnivals, they serve as fanciful celebrations that turn the normal order upside down and therefore affirm traditional boundaries of cultural expression.

Accompanying the show were two educational components that provided invaluable interpretive material. The catalog features an essay by James Ackerman that addresses new concepts of function, particularly in regard to scale and use of materials, and an essay by Sarah Bodine and Michael Dunas that points out the continued persistence of a minimal way of working. While Ackerman's observations shed special light upon the non-New York work, the second essay helps to explain the shared perspective of the New York school, one that is not unique to the world of jewelry. The furniture shown at Art et Industrie, for example, reveals the same persistence of minimal approaches, interest in weight and perceptions of weight, and emphasis on surfaces. The catalog also illustrates at least one piece by each artist and included a short biography of each artist.

An artists' forum, in which I participated, was another essential interpretive component. Nine of the 17 artists explicated their ideas, methods of working and choices for the exhibition to other jewelers and students. The chance to discuss intent and performance was indeed exciting, but it also emphasized the importance of properly presenting content-laden jewelry. The objects speak as themselves but not for themselves. Titles can often be helpful as in the case of Hamlet's work, but also they can be cryptic. Complex verbiage, like a lack of wearability, does not automatically mean conceptual content. For this exhibition, even the use of the word epiphanies as defined on the text panel in the show - "a manifestation of perception of the essential nature of something, a single and striking intuitive grasp of reality" - seemed pedantic, intellectual posturing. Clear, explanatory narrative text, as short as five or six sentences, would greatly enhance a viewer's understanding and evaluation of concept and execution. While the curators used blown-up photographs of Bally's, Parcher's and Jocz's work to provide some sense of context, artists and curators should devote more attention to the interpretation of their objects. Through short labels, arrangement of a series or new technologies such as videodiscs, we need to better explicate the strong but often mute objects for both colleagues and the general public.

The Artists Foundation and the three curators should be applauded for this pathbreaking exhibit and its related programming, all achieved with a very modest budget. One can quibble with certain flaws: the inclusion of several drawings isolated by themselves in a back corner of the space, suggesting their role was an afterthought; Thomas Gentille's decision to send older, less adventurous work; and the appropriateness of John Iversen's cast production work. But the overall effect was very positive. The exhibition has provided needed energy and refection to the field of studio jewelry, yet is has also pointed out the difficulties of organizing and interpreting it. It should prove exciting to see how future shows will be organized and how jewelers and curators discuss such issues as changing social boundaries for function or the difference between fabrication, assembly and manipulation.

Edward S. Cooke, Jr. is associate curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The catalog of this show is available from Artists Foundation, 8 Park Plaza, Boston, MA 02116. "Jewelries/Epiphanies" travels to the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Czechoslovakia February 21 - March 24, 1991.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

John Baltrushunas White Winter

Pro-Art, St. Louis, MO

November 17 - December 31, 1990

by Teresa Callahan

The theme of this show was jewelry that reflects visual qualities typically associated with the winter season. The visual drama is achieved by the omnipresence of icy sterling silver. Although all of the pieces echo nature, a mood is conveyed that elevates this work beyond mere imitation or representation.

When addressed individually, each piece is a composition of several constructed elements and hollow segments. The artist relies heavily on textural variation, achieved through hammers, subtle roll-imprinting and liber techniques. The craftsmanship, deliberately neither sophisticated nor crude, imbues each piece with a memorable sensitivity and spirit that would not exist if the maker's hand were not evident.

Of particular success are the pendants, Snow, and Branches I and II - splendid examples of cocoonlike vertical forms, replete with undulating curves and wrapping sinews that scent to promise a future metamorphosis. Stark, deceptively simple exteriors capture a peculiar grace that echos the nature reference.

The pins of the "Eternal Promise" series are more reminiscent of the artist's earlier work in their personal geometry and juxtaposition. It is significant that he has worked extensively with patinas, colorations and aerospace metals for the past decade. This refined exhibition of silver marks a return to a certain classic sensibility for Baltrushunas. Perhaps like winter itself, it shelters a new beginning.

Teresa Callahan is a writer living in St. Louis.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Jewelry of Barbara Heinrich

GZ Art+Design Spots 2008 1

Hydraulic Die Forming for the Artist/Metalsmith

Virtual Engraving in Matrix

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.