Metalsmith ’92 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

32 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1992 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Sharon Portelance, Bruce Metcalf, Betty Helen Longhi, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sharon Portelance

Wheeler Seidel Gallery, New York, NY

May 21 - July 2, 1992

by Carolanne Patterson

In the recent exhibition of Sharon Portelance's work, one encounters a group of objects that relate directly to nature through their organic properties yet allude to a more personal, emotionally charged intimacy. The artist explores her own femininity and vulnerability through contradictions resulting in intended ambiguity. The inconsistences in the forces of human nature and the implied conflict between inside and outside are continually explored. The forms make direct reference to the vessel, although the vessel as departure point seems the more important issue. Through handling of the material, the variation of surface texture, and the overt processing of metal, nature and the abstract converge with irregular consistency.

Nest-like forms, the smaller and most endearing work in the group, establish fragile connections among themselves. Inversion includes a cocoon-shaped nest, tenuously connected, dangling with fragile beauty from an arch-shaped armature. Next to it lies a similar shape, unconnected from its accompanying armature, lying on its side. A sense of danger is evident, the unpredictable assertions of the overwhelming world. These lyrical shapes, formed by swirls of paper-thin metal and wire, correspond structurally to the architecture of a bird's nest; however, these nests suggest a bed of sharp edges, a home of a precarious nature.

Hidden within several of the smaller pieces are forms that contradict the predominantly organic aesthetic. A small sewer grate reveals itself within a vessel. A needle or spoon shape marks the introduction of industry. Manufactured and mechanical references are placed together with pods, cocoons and odd organic shapes which uncoil and intertwine, mysteriously coexisting with apparent ease.

Matters of the Heart incorporates the anomalous use of gold to illustrate the precious nature of this small shadow-forming piece. A private, nonspecific richness is cast upon the work, which glimmers in the surrounding decay. The simplest of the group, it stands out among the spoiled remains of its environs, providing an almost celestial quality.

Self-Portrait, one of the larger works, illustrates the vessel merging with the female figure in an almost macabre yet balanced and forthright way. The sexuality of the piece is suggested through life and birth rather than desire and pleasure. Although the structure seems to perish at certain angles, growth is evident in the form of leaves and blossoms emerging unexpectedly and erotically from the small of the back, which is, not coincidentally, the middle of the vessel. The crumbling form reveals a hidden or latent life as a small shoot grows from a dead and putrefying tree.

The larger forms utilize the electroforming process on an unusually vast scale and become disparate to the smaller, more delicate pieces. Each piece exposes its wire skeleton, covering only enough to semi-complete the form. The figural aspects of these pieces create a more cumbersome whole when compared to the smaller constructions of thin copper and wire. As sculpture, they confront issues connecting anatomy and autobiography, archaeology and history. The artist's dramatic cutting into these forms suggests a violent undertone. Imperfections caused by the maker and the surface of acid-treated copper create an equally enigmatic display of violation.

These exploratory works pay homage to the beauty and intrinsic value of copper. The use of patina is minimal, mostly achieved through the heating of the metal. The larger pieces are doused with a layer of oil, creating a shiny yet darkened surface. Darkness prevails among the earth-toned, autumn colors, the perishing of organic material being Portelance's main concern.

Most of the forms are hollow and vertical, yet the traditional term hollowware cannot be attributed because of their fragmentary nature. That which disintegrates embodies our social experiences. The archetypal forms of the vessel and the nest inherently touch something that is essential in the chord of human emotions. With these works, the viewer can become aware of what has passed and what the future holds. Reality is limited, but through these dialectical references, one is left with the questioning aspects of Portelance's challenge.

Carolanne Patterson is a graduate student in the metals department, State University of New York, New Paltz.

Bruce Metcalf: New Wooden Jewelry

Jewelerswerk Galerie, Washington, DC

April 2 - 23, 1992

by Lee Fleming

Bronze powder, oil paint and found materials transform carved pieces of maple into social commentary in the most recent work of sculptor/jeweler Bruce Metcalf. "Guerilla jewelry" in the best sense, they demand a great deal from both wearer and watcher. Whether brooches or neckpieces, the objects are not shy about confronting the beholder, requiring that we focus on the ironic political and social messages conveyed by Metcalf's materials and forms.

His pins feature cartoon-like figures that seem a cross between Bart Simpson and E.T. the Extraterrestrial, yet their sly cat's eyes and curled fetal forms also evoke less innocent aliens. In Wood Pin #73 (1991), one of these creatures is shown in profile, a single huge glass cat's eye studying the brass cube held gingerly between its two thin "arms." Its enigmatic attitude arrests our attention, no mean feat considering Metcalf has covered this homunculus with pinto-spotted felt. Even when the artist confines himself to relatively tame surface treatments, as in Wood Pin #64 (1990), where bronze powders give a rich texture to the underlying maple, the addition of a coxcomb and a grinning, brownish-white football-stitch mouth imparts a mock-macho twist to his figure.

Male aggression is definitely one subject under scrutiny, as two playful but pointed pins from 1991 attest. Officially labeled Wood Pin #80 (Testosterone Guy) and Wood Pin #81 (Testosterone Guy), their titles ensure that we don't miss the message. In one, an amorphous, tiny-headed figure somewhat like an early Henry Moore crossed with a marine egg sac brandishes a massive studded club, almost matched in size by a rampant penis/club. His partner hoists boxing gloves and boulders overhead, but the main attraction is the gnarly penis that rises slightly higher than his "shoulder." The comic yet biting visual puns keep the commentary light without diluting their powerful effect.

However, the show's tours de force are the wooden neckpieces that demonstrate Metcalf's superb jeweler's sensibility and extraordinary feel for texture and telling detail. In Wood Neckpiece #6 (1992), our eye skips around, from smooth, lustrous wooden shapes like elongated barbells or wooden pieces like those advertised to help massage the neck, to balls of cork, to exquisitely veined and finished wooden eggs, to spiraled driftwood twigs, to a beautifully gold-checked bead, finally fetching up at the pendant, a dragon-toothed alien whose round glass pupil and open mouth indicate considerable, if indefinable, distress.

Wood Neckpiece #5 (1992) is the most ambitious - and successful - piece in the exhibition. Again, we have the wooden barbell-bone-massager as the section that rests against the neck. But the counterpoint of textures that Metcalf undertakes to hang from this starring point is startling and daring. Segments of wood, still rough with bark, join up with lovingly polished wood balls and eggs in connections that, once in place, seem inevitable but must have required enormous thought to exploit the continuum of a sheen, a texture or a grain direction.

Plastics and metals are deftly integrated. A geometric shape cut from Corian seems just right for its place. Lengths of hardware and steel cable, rubbed in some cases with pigment to visually "join" the natural and manmade materials, complement rather than war against the organic objects with which they share the necklace. The piece ends in a large, purplish bronze creature with staring eye, an unnerving climax to the subtleties of the necklace and yet, again, somehow just right. Metcalf's greatest gift seems to be his uncanny ability to blend elements both absurd and beautiful into a coherent and striking whole without lessening the impact of either aspect.

Lee Fleming, a freelance critic, writes for City Paper in Washington and several national art publications.

Of Magic, Power & Memory: Contemporary and International Jewelry

Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, WA

April 25 - May 31, 1992

by William Baran-Mickle

The Bellevue Art Museum has the unusual position of being located in a major shopping mall in the burgeoning Pacific Northwest. It is therefore a fascinating situation that a major international jewelry exhibition peers down on boutiques and cafes and yet is the ancestral home of a rich variety of native cultures. Keeping this heritage of place in mind, curator Diane M. Douglas included works from many native cultures from around the world. One-third of the exhibitors are from the region itself. The 160 works on display were created by 39 makers.

Two very special aspects of this exhibition should be pointed out. The first is the extensive geographic scope of works from Northern and Southern Hemisphere countries. Interestingly, only a handful of works are anthropological in nature, that is, are not contemporary works of the last two decades. This is useful to connect traditional adornment to contemporary ornament.

The second aspect is the conceptual scope of the works chosen. The diversity of approaches ranges from actual jewelry, being decorative, wearable and meaningful, to large installations that reflect and expand on the idea of jewelry.

Wall statements and a brief catalog accompanied the exhibition. They were particularly helpful in understanding the installation works by Mary Ann Peters and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman. Their works are as far-reaching in their conceptual statement as Otto Kunzli's shoulder brooches of hard foam and wallpaper were to the 1980s (four of his works were in this show). These two women have pushed the envelope of what the idea of jewelry can be.

Peters' installation, Find the Syrian Boys, occupies an entire room. A large aluminum box rests heavily upon a wild, uprooted tree trunk. The surrounding walls are painted in a melancholy array of colors where bits of words emerge revealing names. The top of the box is open yet nearly opaque due to a deep-walled, closely patterned grid. Not until the viewer leans over and physically inquires of its contents do shadowy photographs appear. The photographs are old family portraits of Peters' family at the time they emigrated to America from Syria. The sole process and installation operates on the idea of the cameo portrait.

Jill Slosburg-Ackerman's installation, Sighting, is a trapezoid-shaped cloister 5 feet 2 inches tall (the artist's height) of thick white plaster walls. It is open at the narrow end, just wide enough to enter. This challenges one's sense of safety and future. The inner walls have jewelry-like objects embedded in them. The root of this concept comes from sarcophagi in a 12th-century monastery in Montmajour, France. Slosburg-Ackerman sees this object-place as a grave-vessel. This one speaks of its maker, its details keyed to the maker's life and work. Its design successfully creates an emotional experience.

There were other examples of architectural jewelry. Pam Beyette's Industrial Medallion, for instance, stretching 18 feet long, is made of industrial debris such as copper pipe and computer circuit boards which are bound in the center and bow gently to either side. The found materials have been re-embellished with color and foil to visually enliven the presentation. These works of architectural jewelry, like the previous ones, clearly attempt to join their sister media in crossing boundaries from their jewelry form status to that of architectural ornamentation and fine art.

Micki Lippe's three sterling pendants called Spirit Houses are hope-filled architecture for the person. Simple in their design, they are the new age, nondenominational version of the jewish mezuzah. Europe an jewelers Otto Kunzli, Gerd Rothman and Manfred Bischoff also display jewelry as body architecture in ground-breaking styles that use unlikely materials and question what jewelry is and where it belongs. These works felt slightly out of place in the context of a body of work overwhelmingly dealing with spiritual and cultural seriousness.

Personally and culturally expressive works were well represented. Denise Wallace's narrative pins and belt show intricate Aleut figures with masks that open to reveal sensitively rendered bone faces. Walrus Shaman, Dancer and Woman Figures locate her contemporary personal and culturally shared issues in a way that respects traditional roots, though with contemporary flair and innovation.

Works from other native cultures (Thailand, Africa, Plains Indian and others) were refreshing to see and seemed to show contemporary works with their traditional purposes and meanings intact (i.e., wedding ceremonial accessories). A substantial number of what I will call "American-International" artists appeared to be purposely co-mingling the artifacts and styles of various cultures, to comment on our own society or perhaps to bask in the beauty of other cultures.

This axis of the exhibition was exemplified by Ramona Solberg, who utilizes a respectful appropriation of cultural artifacts, and Ron Ho, who uses them for abstract portraiture. The next generation may well be represented by Kiff Slemmons and the collaborative works of Kim Overstreet and Robin Kranitsky. Slemmons appropriates the Plains Indian chest-plate format for two neckpieces titled Hunt and Pectoral and Sticks and Stones. She replaces the rows of beadwork with crisply sharpened pencils or typewriter key structures to create the pattern field. Overstreet/Kranitsky make use of found objects to present social issues and make references to individual emotions such as loneliness. These have an odd yet intriguing presence.

Jung-Hoo Kim's Life in the Circus and Sara Sanford's jewelry stand out as spare poetic works. The exemplify the strengths that contemporary reverential jewelry can have, and spoke for the Power and Memory segment in the show.

There was an interesting group of artists who use cow bone for contemporary scrimshaw work. Of these, Stuart Buehler's series For the Bone Man (for example, He Comes in Many Guises, Many More Than Christ) stands out for its contemporary imagery, arrangements of elements and coloration, as well as a high degree of sensitivity to the bone as a sophisticated material. Susan Ford's work is closer to traditional imagery (animals, insects) but shares Buehler's finesse for re-energizing a folk art practice.

The overall quality of this exhibition was extremely high. With the inclusion of works by Robert Ebendorf, William Harper and Kai Chan, to name just three, there were far too many works and far too many subissues to mention. It would have been wonderful if this exhibition could have lived longer as a traveling show.

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer living near Rochester, NY.

"Metalworks" Metal Arts Guild Juried Exhibition

Velvet DaVinci Gallery, San Francisco, CA

April 22 - May 15, 1992

by Kris Patzlaff

The Velvet DaVinci Gallery in San Francisco was host to the Metal Arts Guild juried members exhibition entitled "Metalworks." The Metal Arts Guild, whose membership is based primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area, has a long history of providing exhibition opportunities, lectures and workshops. The jurors, Dawn Nakanishi, Chuck Escott and Mike Holmes, chose 71 pieces representing 27 jewelry and metal artists from the membership.

The collection of work was predominantly jewelry, with some sculpture and other objects as well. Among the nonjewelry works was Jeff Wind's bronze sculpture Farewell to the Good Seuss: Death in a Child's Eyes, which invited the viewer to explore the tenuous positioning of identifiable objects piled "so high" in characteristically Dr. Seuss fashion. Unfortunately, this sculpture was presented so that is was difficult, if not impossible, to walk around, as it demanded the viewer to do.

A creation of both technical and physical beauty was Jo Ann Donivan's untitled box. The lid was fabricated with pierced and chased silver, creating vines and leaves with a veil-like quality over polished agate. The bottom of the box was constructed of wood, leading the eye to the delicate use of mokume-gané for the panels of each side of the container. Donivan's attention to subtle detail and surface treatment is tastefully ornate, a testimony to her understanding of scale within design.

Diane Orwell's fabricated silver box, Reliquary to the Child I Was, was more narrative in nature. Adorned with wings and a rose quartz stone on the lid, the box was placed upon a pedestal of four cast silver babies. Held within was the artist's baby tooth, lying preciously on a pink satin pillow.

Most of the jewelry in this exhibition was conceived in silver, brass and copper, and stones. However, the concerns, concepts and devices expressed and used by the artists went in many different directions. The only piece of gold jewelry was Gloria Bumb's delicately woven bracelet of gold wire with an exquisite tube catch encrusted with tiny gems on the surface. It was a fine example of goldsmithing.

Diane Robert's earrings investigated hollow forms of geometric shapes with clean line and surface treatment. Alexandra Connell's brooches, Flying Fish and Flounder, were representational depictions of fish. The carved bone bodies were complimented by the etched silver surface of the fins in these well-designed and constructed pieces of wearable jewelry.

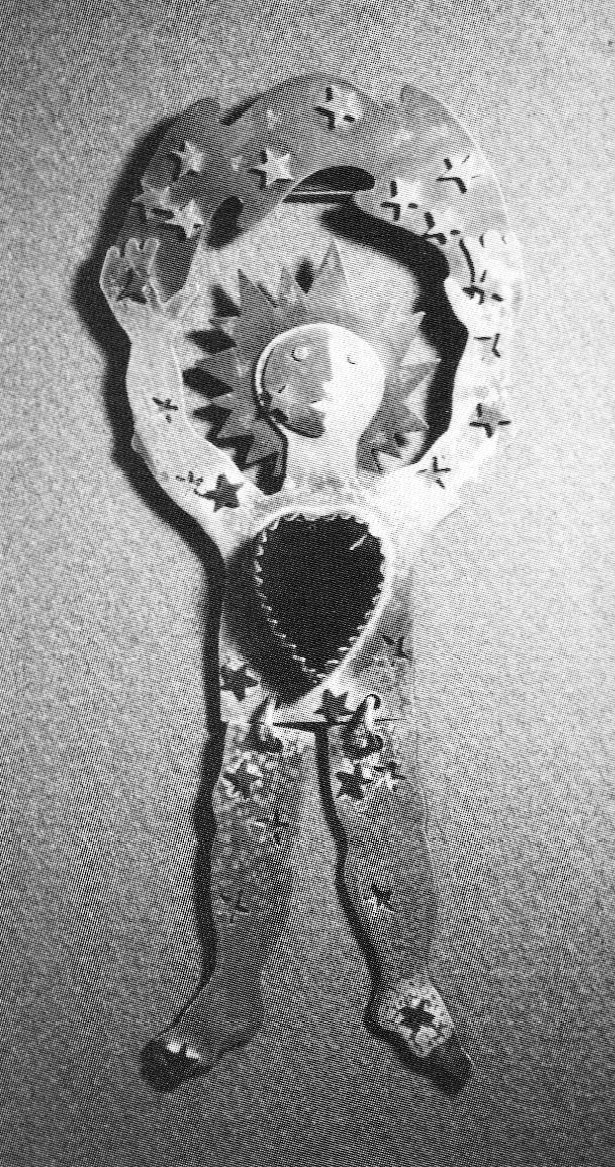

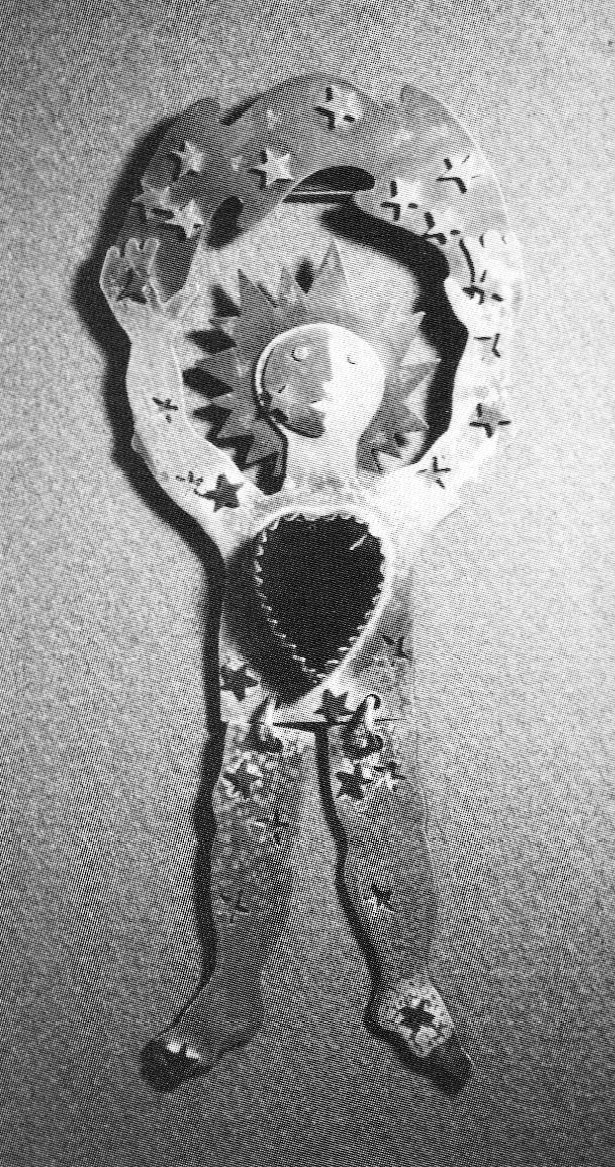

Among the jewelry in the exhibition were works that displayed a strong sense of narration. Judith Hoffman's pieces, fabricated of silver, copper, brass and found objects, were of beings that related a story, myth or comment. Now She Holds the Sky in Her Hands was a brooch of copper and silver in the form of a woman pierced and textured with stars. Most of the woman's torso consisted of a heart-shaped glass bead; her arms extended over her head holding a piece of the night sky. A relationship was created between the darkness within us and the darkness of the night sky, and mystery they both hold. Other pieces worth noting were Carol Windsor's brooch, Heart Piece, a cast silver broken heart with delicate streams of assorted colored stones flowing outward, and Katie Leong's elegantly conceived textured silver chopsticks with pillows.

This MAG exhibition is the first since the one held during the SNAG conference in San Francisco two years ago. Interestingly, it included many jewelry and metal artists who are not as well known as those in the prior exhibition. It was refreshing to see the less publicized work of these talented metalsmiths.

Kris Patzlaff is a jewelry artist and teacher living in Trinidad, CA.

Revolving Techniques: Clay, Glass, Metal and Wood

James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, PA

March 28 - May 24, 1992

by Gail M. Brown

Three curatorial points of view and four media explorations were integrated to present a survey of the "revolving" process at the James A. Michener Art Museum. The exhibition placed an emphasis on education: descriptive statements were posted to explain mastery of process and technique and to reference the relationship to mass production. The manipulation of process was examined, pointing to individual investigation for creative expression. There was reference made to the process-as-metaphor for content-related concerns.

The nature of the work exhibited relied heavily on function, control, elegance and symmetry. The 26 artists represented were, in most cases, well-known and in mid-career. The installation spread the examples of each medium throughout the gallery. That, plus the inability to view much of the art closely or from all sides, interfered with the emphasis on education. The medium with the broadest range of expression exhibited was metal.

The form of Lynne Hull's copper Basket #24 (1992) echoes the revolving process. Its symmetrical, accordion-like body is topped with a generous handle of slight irregularity whose gesture warms the classic form. Its mottled surface enriches the serenity of the form, also referencing the historic tradition of turned metal.

Richard Mawdsley's sterling silver Feast Goblet (1985-86) celebrates a wedding and the specific couple being honored. It stands elegantly as a formal statement in the custom of metal vessels. The use of a watchmaker's lathe allowed for the miniaturization of a still life within the design of the stem, addressing the artist's interest in the realism of the 1970s coupled with specific technology.

Wendy Ramshaw, the only jeweler represented, focuses on the presentation of jewelry as sculpture to be enjoyed when not on the body. Her ring stands range from various metals to turned Perspex. Gold Ring With Stand (1990) presents a structure of graduated nickel sections rising as a Deco tower, scored with echoing vertical incisions. It holds a single thin gold ring with a long projectile, ending in a directional arrow which parallels the finger.

Sleek formalism marks the bottlecork sculpture of Boris Bally. In Kalimba (1989), the turned silver, ebony, aluminum and gold plate rhythmically balance function with imagination. The contrast and variety of forms and surface enrich the scale. The investigation of the design potential of this object supersedes its utility and suggests unlimited possibilities.

Laura Marth's turned functional objects of anodized aluminum are imbued with warmth and wit. Spread Knife and Fork (1992) are formed with spirited flare. They combine skilled technique with personality. The spreader is fame shaped with hinged, decorative end pieces. Her palette is rich and subtle; she explores fully the broad color potential of this process.

Boris Bally and ROY collaborate on sculptural objects, their latest a Paleoicon Vessel Series addressing awareness of the environment and the revolving process of recycling. Strong graphic images are juxtaposed with hand-raised silver forms, common and precious metals, old and new. This work integrates historic metal techniques with found objects. Pointless Bowl (1991) combines silver, reused aluminum sign and rubber sheet to create a dramatic vessel, a statement about nonutility and current icons. The work is about contrast in concept and treatment.

The sculpture of the Philadelphia Wireman is made entirely of recycled materials. A large group of this unknown maker's hand-size, abstract pieces were found in the mid, 1970s. In Wire #539 (c. 1970) wrapped wire traps a red cardboard Chicklet box, a metal can lid and a red plastic bike reflector. The freedom of this hand-turned work exudes energy and spontaneity. Its emotional power belies its intimate scale. The enigmatic messages transcend the technique.

The Albert Paley Lectern (1989) of turned steel and brass also raises issues of contrast. The delicate-seeming ribbons which form the pedestal undulate gracefully, working upward to support the weighty top. This suggests both freedom and an underlying discipline of structure. The appearance of spontaneity heightens the drama, as distinguished from the permanence of the materials and the complexity of the process. This juxtaposition makes a powerful impact.

The show serves best as an introduction to the range of possibilities of turned work, inviting deeper investigation at another time and place. The strong work in metal serves well to exemplify the diversity waiting to be explored by the viewer.

Gail M. Brown lives in Philadelphia and writes on jewelry and fine crafts.

Crossroads

Artwear, New York, NY

May 14 - June 14, 1992

by Ellen Berkovitch

There is the very small and the very large, the whimsical and the serious. There is the traditional tweaked in a fresh way and the outlandish rendered familiar. Crossroads, Artwear's invitational exhibition featuring the work of 14 art jewelers from across the U.S., delivers a gamut of vocabularies and techniques representative of the provocative directions of the field. Notable is the integrity of the exhibition's displays with the natural positives of the work, the balanced representation of women and men, and the sense one has, on leaving, of having witnessed a diverse yet coherent breadth of talent that doesn't reveal a specific curatorial bias.

Four of the featured artists - Sandra Enterline, Kiff Slemmons, Bruce Metcalf and Donald Friedlich - have shown work at Artwear before. Ten are new to the gallery: Jill Slosburg-Ackerman. Eugene and Hiroko Pijanowski (working as a team), Rachelle Thiewes, James Cotter, Brent Guarisco, Joe Wood, Randy Long, Tibbie Dunbar, Gayle Saunders and Daniel Jocz.

Tibbie Dunbar achieves outstanding mobility with her Quiet Invasion series of brooches fabricated of rice paper and steel wire. Dunbar describes her work as an experiment with the "insidious." The shapes are fluid but oddly mutant, susceptible to lumps and bumps, much as a piece of detritus blown by the wind off a city street might appear.

Joe Wood, also showing brooches, forms stainless steel cages inside which he nests small alabaster pebbles. Reminiscent (at least in spirit) of Joseph Cornell collages in the way they evoke miniature universes, using a stripped-down vocabulary, the jewelry doesn't sacrifice wearability to its aesthetic.

Less successful by this criteria, to this viewer, are the Oh! I Am Precious paper cord (mizuhiki) neckpieces by Eugene and Hiroko Pijanowski and - at the other end of the size scale - the marble and gold Draperybrooches by Randy Long. Both deserve credit for manipulating materials not common to jewelry. Both are striking, even dramatic. But they fail to overcome an apparent difficulty: that of reconciling the demands of the material with its purpose of human decoration. Although the Pijanowski pieces are threadlike and light, they nevertheless appear cumbersome, performing best on a mannequin form. The marble in Long's work achieves the characteristics of draping common to sculpture but doesn't quite surmount a perception of flatness.

Truly original in the repertoire was jewelry that tweaked the form without sacrificing its application to the body. Brent Guarisco bundles amulets representing tools and utensils into necklace forms, inviting wearer interaction with the shapes and concepts they represent. Jill Slosburg-Ackerman deconstructs pairs (hers don't match) and encapsulates in her jewelry the unity achievable through a demonstration of parts. Bracelets by Rachelle Thiewes and James Cotter manage to hearken to architecture with references that heighten the distinction but don't obscure it.

Finally, Kiff Slemmons presents work that is rich in association because of the homely objects that she makes precious - chewed-on pencils, a 33⅓ rpm record, metal hand shapes. In her ideal world, a piece of jewelry would be made of ice and last only an evening, leaving behind a sense impression on the skin of the wearer.

The good news for the art jewelry community and its devotees is that curator Robert Lee Morris has rededicated himself to providing a forum for the craft at Artwear. It carries a big stick.

Ellen Berkovitch, based in New York, writes frequently about fashion and the arts.

Betty Helen Longhi

De Novo Gallery, Palo Alto, CA

May 9 - June 20, 1992

by Carroll Lee

The finely crafted jewelry and sculpture of Betty Helen Longhi was on exhibit at the de Novo Gallery in Palo Alto, California, this spring. Fabricated from gold, silver, niobium and titanium, Longhi's highly individual work is often recognizable by the colors she produces from anodizing niobium and titanium.

The interpretation of the curvilinear forms found in nature has a long legacy among artisans. Beginning with members of the Art Nouveau movement, craftspeople have been translating these natural phenomena into their own individual perceptions of art in nature for generations. The elongated curve of the stem of a calla lily, the shape of a drop of water on a leaf, the texture of a stone that has been washed by decades of weathering, the changing colors of the seasons - all have found their way into Betty Longhi's visions of color and natural form.

A master of technique, the artist incorporates forging, shell forming and hammer texturing in her pieces. Although she is obviously inspired by nature, her pieces also reflect a preoccupation with the interpretation of movement and space. Her sculpture My Spirit Soars exemplifies this. At 14 inches high and 12 inches wide, the piece is meticulously fabricated from sterling silver and niobium. As the viewer moves around the sculpture, the slightest changes of light on angles provide a fluidity of motion.

As in the case of most of Longhi's works, color, not so much in pigmentation but in what happens to color across a three-dimensional surface, becomes an important element when viewing the pieces. This is especially important in the case of the reactive metals niobium and titanium, where the colors change subtly and only with the viewer's movement. So much of work being done today with niobium is superficial, letting the colors of the metal carry the design of the work. Not so in the case of Betty Longhi's work.

The sculptured plant form of her brooch Grey Wave illustrates the Artist's clever use of niobium to enhance the flowing lines that feed into one another. The repetitions of movement, like swaying reeds, reverberate from the shimmering colors that play with reflections of light. Made with sterling, the piece is set off by two freshwater pearls and diamonds.

Another brooch, Windswept, also uses niobium to enhance its liquidity. A long sweep of subtle curvilinear line suggests a blade of grass that has been bent by the wind, its concave niobium center showing off colors that reflect onto the sterling silver shaft. Two long thin tendrils of 18-karat gold jut out from each side of the piece, wrapping under the far end of the blade, sensuously entwining. Freshwater pearls peek out from the broadest end to complete a quiet elegy to movement.

Betty Helen Longhi is an innovative artisan whose work reflects her strong capabilities at mastering complicated techniques, then interpreting them to fit her philosophy of design. Her jewelry and her sculptures grow our of one another - the jewelry pieces are small, wearable sculptures. Her sculptures are larger interpretations of those smaller pieces. Size determines the amount of movement and reflected light a piece will contain. They are enhanced by her knowledge of chemistry and the manipulation of metals. The combination of these elements results in a very personal statement articulated by an accomplished craftsperson.

Carroll Lee is an art historian who lives and works in Princetown, NJ.

Richard Mawdsley New Work: Architectural Series

Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, MA

April 15 - May 30, 1992

by Susan Barahal

While many metalsmiths in the 1960s were making highly polished hollowware and mirror-finished jewelry in the Scandinavian style, Richard Mawdsley was more interested in revalidating the baroque as a form of artistic expression and in embracing the history of precious metals. After nearly three decades of perfecting his craft and receiving accolades from several major museums, Mawdsley continues to create innovative objects, as is demonstrated by his recent show at Mobilia Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Mawdsley's metal objects combine the intricacy and fantasy of a Fabergé with the mechanical virtuosity of a Rube Goldberg. His creations compel the viewer to closely examine the many meticulous details and to be captivated by his sense of mechanical whimsy.

Mawdsley attributes his fascination with the mechanical to his youth and the many summers he spent on his grandparents' farm in Kansas. He recently returned to the farm and, seeing the wheat-harvesting combine from his childhood, realized how much of an influence this machine had had on his designs. Although Mawdsley never studied engineering, he seems innately comfortable with this world of machines and machine parts. Indeed, it has been the basis of his artistic expression.

The mechanical quality of architectural structures has also interested him, and his most recent work consists of an architectural series using precious metals. Although elements such as columns and entablatures are present in his earlier work, architectural structures now dominate.

The works in this series reveal the artist's almost exclusive use of metal tubing. Mawdsley relies on commercial tubing which he alters and assembles. Round or square tubing is often cut, flared, bent, squashed, engraved and combined with other materials to deviate from its original form. The advantage of using tubing in jewelry design is that it is thin (generally 30 gauge) yet quite strong. Rather large pieces can be constructed that are lightweight and wearable.

Indeed, the Beta neckpiece, depicting a wall fragment, is an example of a large yet wearable piece. This relief sculpture is made almost entirely of commercial gold tubing. Mawdsley engraves the surface of square tubing and forms shapes to look like brick. The complexity and three-dimensionality of these multi-leveled architectural elements are intriguing. One is captivated by such minute details as the pearls, which act as lightbulbs in the sign. However, as imperfect as fragments are, a few lights are missing. Mawdsley indicates the missing "bulbs" by omitting the pearls but leaving their gold post supports. The artist's fascination with technical ability is exemplified in this piece. Since dozens of soldering joints are required, the piece was created in sections and then assembled as a whole.

Another wall fragment design which reads as a classical relief sculpture is a highly textured 18k gold brooch. Again constructed almost entirely from tubing, this piece combines engraved bricks, a flutted Ionic column, a frieze and a bezeled lapis lazuli. The stone's delicate linear matrix echoes the bricks' engraving. One limitation in using tubing is that it does not easily lend itself to achieving organic forms. Therefore, in order to capture the plastic and fluid nature of plaster, Mawdsley uses wax to cast gold, which simulates plaster oozing out between the wall's laths.

His Garden Stairs piece combines his earlier organic corsage motif with the architectural. Although the silver architectural elements clearly dominate in scale and mass, the plant form projects a strong presence and contrast to the straight-edged balustrade. The bush commands our attention, not only because of its placement in the foreground but also because of its bright yellow gold-plated color. The plant is both lyrical and figurative, somewhat evocative of Marcel du Champ's 1911 painting Nude Descending a Staircase.

Mawdsley's work continues to mesmerize us with the abundant use of decorative mechanical flourishes and makes us smile because of its fanciful humor. His art makes us feel good as we realize how far technical and artistic abilities can be stretched.

Susan Barahal is the decorative arts editor for Art New England and teaches art in the Boston area.

Kit Carson

Galeria Primitivo, Santa Monica, CA

May 2 - June 6, 1992

by Dorothy Spencer

Yahoo! The works of Kit Carson came to the Galeria Primitivo in Santa Monica, California, for the month of May. For those unfamiliar with the artist's pieces, they are a wild mixture of outrageous humor that soundly spoofs southwestern and fantasy themes. The objects range from a line of cast jewelry, to handmade, exquisitely crafted, one-of-a-kind pieces of jewelry, to knives, letter openers, clocks, lamps and small sculptures.

These days, with southwestern themes found on everything from toilet paper to bedspreads, it's hard to imagine taking coyotes barking at the moon, cowboy boots or cactus and giving them a fresh new turn. But Carson's work does just that. His bolo ties are made from silver and 18k gold, many set with semi-precious stones. The leather braided thongs have engraved silver tips with cut-out framed scenes hanging from their points. The bolo clasps resemble picture frames or, in some instances, television screens with detailed images set three-dimensionally into the centers. In Alligator/Poodle the artist's irreverent sense of humor is clearly evident as an alligator sits grinning menacingly, a primped poodle clenched between his teeth, the focal point of the bolo clasp.

At first glance at Howling, you can almost hear the melodic twangs of some lonesome cowboy's song from the wide prairie. A second look reveals that the large, minutely detailed silver and gold brooch features a formalized portrait of, not Dale and Roy, but a male and female coyote. The happy couple, their muzzles raised in unison toward a gemstone moon that sits atop an archway of bones, is dressed in dude-ranch western attire; additional bones along with musical notes hang from the bottom of the frame.

The artist's special brand of satire coupled with an extraordinary eye for detail gives these pieces an individuality that immediately separates them from the coyote and cactus jewelry that has so completely saturated the mainstream market. Carson's ability to hone fine pieces from precious metals and semiprecious stones carries over to other objects as well. His Cowboy Clock is indicative of this quality of craftsmanship. Using silver, brass and copper, he has designed a functional object that retains the artist's sense of self. A coyote howling at the moon, rabbits scampering across the sand, a buzzard circling overhead and a skull lying amongst the sagebrush are all worked around the outer case of the clock, providing a fresh take on an old standard scenario, complete with a copper snake as the second hand.

Carson's reinterpretation of the ordinary, creating a new twist, is most obvious in his lamps. In Cowboy Liberty Torch he has taken many of the symbols associated with the Southwest, such as barbed wire, wood, goat horns and turquoise, and fashioned them into a functional totem. These homages to the lifestyles of the Southwest have been poked fun of with the discerning eye of a craftsman.

In addition to the southwestern themes, several of Carson's handmade pieces feature Alice-in-Wonderland characters, including a brooch entitled Queen of Hearts on TV. The television screen once again sets the stage for a highly satirized, cartoonlike image of a queen of hearts looming, three-dimensionally out from the screen. Crafted from silver and copper, the queen's portrait is set with tourmalines and garnets.

All of Carson's objects require careful scrutiny. The details incorporated in his pieces turn what seems to be the obvious into nor-so-subtle satirizations of some of popular culture's most prevalent themes. The fact that his work is so successful relies as much on his technical skill as it does on the playfulness of his subject matter. So as the sun sinks slowly in the west and those old coyotes come out to howl, you can bet your boots that from the reception of Kit Carson's latest exhibition, he'll be hard at work saddling up for yet another exciting show of skill and craftsmanship.

Dorothy Spencer is an arts consultant and writer based in Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

William Harper: Artist as Alchemist

Metalsmith ’93 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

GZ Art+Design Spots 2005 4

GZ Art+Design Spots 2008 1

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.