Metalsmith ’92 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

11 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the [year] [season] issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Judith Kaufman, John Nihart, Elisabeth Holder, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Judith Kaufman

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, California

September 3 - 29, 1991

by Charlene M. Modena

At first glance, the words "lush" and "baroque" would seem the appropriate descriptive terminology for Judith Kaufman's jewelry. Although there are the restless opposites and the typical blend of color, light and movement found in the purest of the baroque, a closer look at these breathtaking and daring pieces brings one to an entirely new vantage point.

Sensitively integrating historical and Futuristic themes with vivacity and beauty, Judith Kaufman's jewelry becomes, in a sense, intergalactic. Collaging finely detailed cutouts reminiscent of glyphs, cuneiforms and fragments of star charts with brightly colored gems and ancient glass fragments, she shows us how to travel not only between planetary galaxies but between galaxies of time as well. This intergalactic framework, combined with the artist's ingenuous delight in materials and color, creates the fabric for a voyage of enchantment and eloquence.

The one-of-a-kind pieces utilizing precious and semiprecious stones, Roman glass and high-karat gold yield the glowing surfaces of the alchemist's crucible. They also speak of spontaneity in the creative process. Judith Kaufman states, "When I sit at my bench and begin, I have absolutely no idea what the piece will look like until it's finished, making the process both frightening and exhilarating."

This combination of creative playfulness and focus moves beyond simply looking at and seeing a palette of "thousands and thousands of stones on my workbench" in an assemblage with gold and silver. It is, rather, the outcome of vision, the vision that early Surrealists recognized as an alchemical blend allowing materials and images to work with and through the artist. Judith Kaufman stares that in a world of planned and overplanned technicality and computerized precision she has chosen to "hold on even tighter to my trust in spontaneity and serendipity."

Although there exists this parallel in process with the early Surrealists and many other artists who have forsaken preplanning for the spontaneous, Kaufman credits the painted and gilded surfaces of Gustav Klimt, himself from a family of goldsmiths, as a major influence in the luminous, "puzzle-like" collaging seen in her work.

A brooch of pink and green tourmaline crystals, diamond baguettes and 22k yellow gold exhibits a playful inquiry into rich textures and colors. Geometry and movement are combined with gemstones and high-karat gold to create a small universe which in one moment appears as a mysterious topography, and at another as a small, wondrous ship sailing through space. Another pin, delicately articulated and densely rich with amethysts, moonstones, tourmaline crystals and pearls with green and yellow 18k and 22k gold, dances through time as both an Aztec headdress and a celestial scepter.

Judith Kaufman is self-taught and committed to the intuitive and unorthodox. Her steadfast belief in her own process and work has served her well. She has created a world of wonder and beauty for all of us to share.

Charlene Modena teaches jewelry and sculpture at the Academy of Art College in San Francisco.

John Nihart

Dawson Gallery

Rochester, New York

September 6 - October 8, 1991

by William Baran-Mickle

The recent exhibition of sculpture in steel by John Nihart represented a suite of constructions mostly completed over a relatively brief period, the summer of 1991. This makes the presentation fresh and insightful of a place in time and of a consistent process and dialog between the artist and his creations.

There were two small sculptures set among six large freestanding sculptures. The smaller works tended to look like scale models due to their presence among overpowering relatives. What they gained for their size was a strong, intense energy that emanated from their fabricated character, with heftier edges and more squat characteristics. What they lacked, by comparison as well, was the spaciousness and solemnness of expression gained from the greater scale and sense of space of the large works.

Makimba, for example, was the most animated and active form in the show. Like several of the larger works, it has an unmistakable animal or insect-like character. Makimba looks as if it is backing away quite suddenly. The larger works, such as Bird Totem, standing 6½ feet, are stilled, as if their motion simply stopped. Makimba plays to the viewer's own size. Perceiving ourselves as larger and more powerful, we are in control of the imagined object, imagined situation and therefore easily play with the sculpture without fear.

Nihart builds a sculptural language with forms, shapes and gestures that include an array of circle/discs which are used full, quartered and halved and then curved, folded, spliced and cut. All of these pieces are joined in a remarkably successful succession of points. They are fabricated in a continuous, interactive style and mounted on tripod bases. These joins effortlessly begin and end; they fade into other such floating elements with logical lines that merely extend the forms into yet a new plane or level. There is an obvious stylistic kinship that Nihart's sculptures owe to Constructivism and Futurism, yet Nihart maintains his distance from them as well as consistently adds his own attitude and expression. The seriousness of Constructivism and Futurism is relaxed by Nihart into an abstraction that is animated, friendly and very approachable.

The four white sculptures in a set are perhaps the most successful of the show, as they are read simply as form. Their technique is obscured. For this same reason, they are also isolating from our (human) experience of them. The three rusted, natural-toned works relate to our earthiness, which adds weight and grounding in the viewer-object negotiation.

In Nomandi, flat circles or circle parts visually spin around a slightly bent central stock, throwing curved ribbons out and upward. The central stock is balanced by two other legs, each demonstrating the tension of holding up energy, one by bowing, the other by its thin leg being interrupted - jagged and broken. Typical of Nihart's works on view, the sculpture continues to change form as observed in rotation around the work; and typically, in so doing, the viewer is engaged as a part of the sculpture, finding and integrating new vistas. Nihart provides a great family of forms to look at. The human scale of the works accentuates this dialog.

Star Dancer, Korusai and Water Spirit relate together as instruments, or symbolic methods of capturing and measuring space or essences. Korusai looks like a sextant or sun dial (or perhaps a moon dial?) with a heavy, shifting arc opening to the sky. Its deep earth tone seems to absorb the information and transfer the essences of it through its tripod legs, represented by a large lightning gesture, a solid stiff, tapered leg and a mysterious tapered leg with two humps. What the viewer makes of this, or any of the sculptures, is the engaging of their personal imaginings with a traditional thirst for the mysterious and playful.

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer living near Rochester, NY.

Metalwork '91

Washington Guild of Goldsmiths Sixth Juried Exhibition

Target Gallery, Alexandria, Virginia

December 1, 1991 - January 5, 1992

by Dalene Barry

The Target Gallery in Alexandria, Virginia - a small, elegant, pearl, gray chamber - was the perfect backdrop for the dazzling array of works in "Metalwork '91," the sixth biennial exhibition of the Washington Guild of Goldsmiths.

Most of the 75 works were jewelry. The thriving membership of the Washington Guild, as well as dozens of sibling organizations across the country, manifests an ever-increasing enthusiasm for wearing beautiful, thoughtful and sometimes provoking ornaments. These groups also encourage the creative pursuit of discovery in those who choose to make these objects - no matter whether the individual is a full-time goldsmith or a nonprofessional adventuring spirit looking for personal fulfillment.

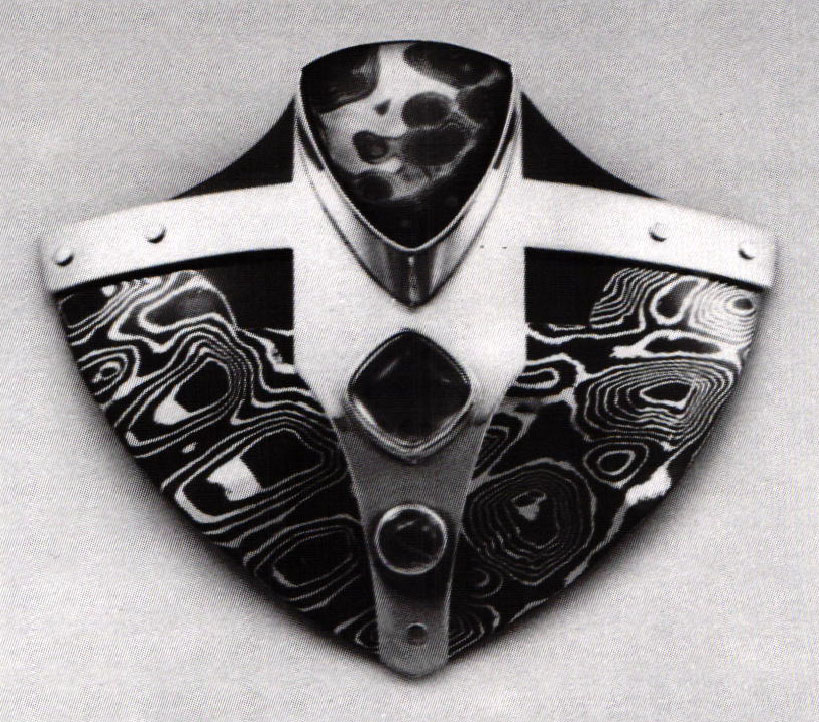

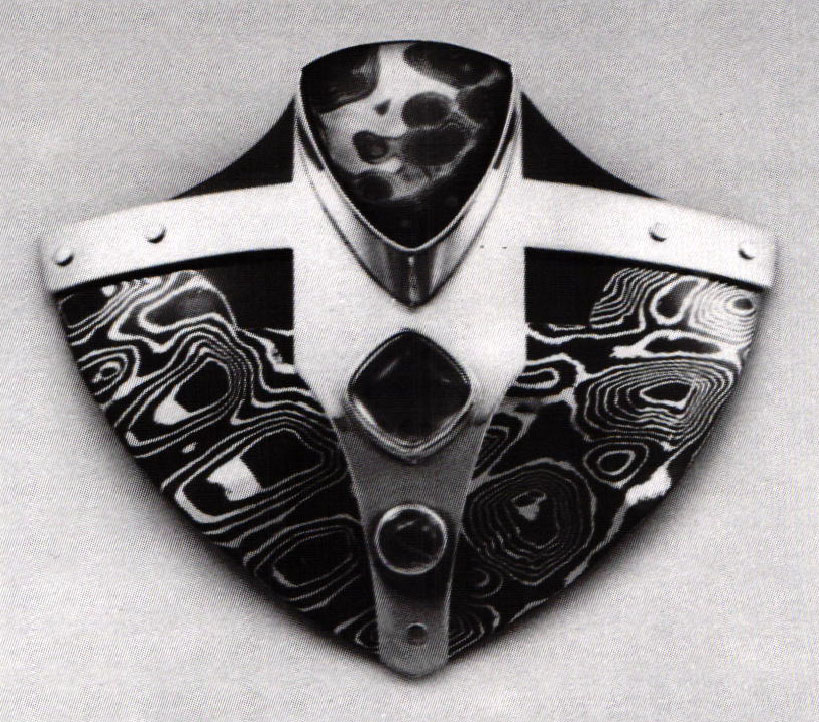

Deborah Dubois's Cornelius Vanschaak Roosevelt brooch combines gold and rhodolite garnets with black slate and black cord in a 3-inch composition of lines suggestive of an underwater hideaway. The jeweler's love of materials is evident here, with the same master craftsmanship attended to a chunk of stone, a snippet of plant life, semiprecious gems and 14k gold. Rosemary Gould's Shield Series brooches are reminiscent of a time when metalsmiths were employed to arm soldiers as much as embellish fine ladies and gentlemen. The powerful beauty of Shield Series #3, which won Jurors' Special Recognition, is enhanced by the intricate patterning of mokumé-gane. The prominent cross-bar in sterling silver adds strength by setting the compact boundaries in this representative piece.

When we place ourselves near the surface of water and see objects both from above and below the water line, our view is split slightly, though nothing is out of focus. The sterling and 24k kum-boo frame for Hyung Kyu Lee's Seascape brooch illustrates this vision, shifting the titanium seascape slightly, inviting the viewer to a new perspective. Lee's brooch also received Jurors' Special Recognition. Betty Helen Longhi's brooch, another Jurors' Special Recognition, is a convergence in line and materials. Flares of anodized niobium burst from bands of 18k gold/sterling bi-metal, stopping short of a central crevice to reveal freshwater pearls emerging from golden filaments. Summerscape '90, Komelia Okim's shoulder piece, juxtaposes abstract shapes and colors of sterling, 24k kum-boo and anodized niobium in a dazzle of color and golden glow. Okim's unique mastery of the technique she has taught so many others is evident in this Jurors' Special Recognition work.

Gretchen Raber, another Washington master, illustrates her affinity for architectural line in a pair of tourmaline earrings set in 14K gold and in her Mathematical Notation brooch of seemingly random elements which are, in fact, a fascinating study in well-conceived counterbalance. Other jewelers and works highlighting the Washington Guild's excellent collection included the distinctive gem-studded multimedia Strata II brooch/pendant by Barbro Eriksdotter Gendell; Susan Sanders's dynamic brooch of onyx, 14k gold, watermelon tourmaline and diamond; Karen Werth's mixed-media brooch. A House for Nine Muses, and Douglas Zaruba's smashing 14k gold and diamond cufflinks and shirt studs set.

There were disappointingly few exhibits other than jewelry, but these select works were superbly crafted. Allan Abrams's Tree of Life menorah of sterling and hand-blown glass spins upward and out from a pedestal; Jazz, Cynthia Corio-Poli's enamel-on-copper wall hanging, evokes chords of Gershwin; Larry Lewis's table sculpture From Our World, Don't Look Too Close offers a bit of personal whimsy in mixed metals and flowing Plexiglas.

Jurors for "Metalwork '91" were metal artist Ronald Hayes Pearson and gallery owner Sheila Nussbaum.

Dalene Barry is an enamelist and writer living in Washington, D.C.

Elisabeth Holder

Jewelerswerk Galerie

Washington, D.C.

September 12 - October 3, 1991

by Lee Fleming

For more than a decade, Elisabeth Holder's commitment to jewelry as interactive sculpture has differentiated her work from that of the mass of artists who take their inspiration from pure geometry. Holder's rings, brooches and bracelets don't simply invite the wearer to assist in their arrangement; they require us to insert, overlap and personalize what would otherwise be impersonal cubes, circles and arcs.

In her recent show at Washington, D.C.'s Jewelerswerk Galerie, Holder's hallmark rings and bracelets from 1987-88 were joined by necklaces and brooches created during the last 18 months. The juxtaposition underscored Holder's new direction - a change in finish and function subtly achieved, yet still striking.

Her "old" approach is exemplified in a 1987 monel, gold leaf and stainless steel bracelet. A ball-and-socket joint allows an expressively textured solid arc to be swung up outside the containing circle; once the bracelet band has been slid onto the wrist, the arc piece clicks down into place, securing the bracelet. The wearer "collaborates" by fastening the catch, but Holder still controls how the bracelet will look once fastened.

The same process applies to many of her 1989 rings, tiny sculptures of bronze and steel with grooves into which we must insert separate square bands before the piece is complete. Off the body, these objects can be pieced together in varying compositions, like miniature minimalist sculptures. But as with the bracelet, there is one "right' way to fit them together in order to wear them.

In her 1990 cube necklaces, Holder begins to move away from the worked, oxidized and gold-rubbed surfaces of earlier pieces, using subtly brushed silver, zinc and stainless steel. At the same time, she allows an element of randomness to enter into the way a wearer might arrange her jewelry. Her zinc cubes may fit together in positive-negative perfect geometries when off their steel circlets, but on the body, they not only break apart but conceivably can be rearranged by the wearer.

This transition - from limited interaction to enormous freedom to take the artist's work and make it our own - culminates in an impressive 1991 series of brooches and pocket pieces. The brooches, composed of pairs of long, hollow forms of pierced bronze or silver, form rhomboids or rectangles when at rest. The density of the pinpoint piercing varies, so that at times we're aware of the solidity of the shapes, while at other times they seem to dematerialize into a shadowy screen.

This shift in the way Holder works her materials is matched by a new approach to functionality. The wearer can create one-of-a-kind pieces simply by running a long pin through the holes of the two pieces in any combination fancied, and the possibilities are endless.

Holder's most impressive offering, however, is her witty substitute for a pocket handkerchief. These pocket pieces of fine silver glued over wood consist of squares placed in the pocket, with other pieces attached to the edges by hinges. By rotating these appendages, the wearer can create literally "outstanding" wearable sculpture that may protrude into space for several inches or be arranged to hug the body. Thanks to Holder's willingness to challenge the wearer's inventiveness, the choice is ours.

Lee Fleming, a freelance critic, writes for City Paper in Washington and several national art publications.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

10th International Biennel of Enamel

Gorham Masterpieces in Metal Exhibition

35 Years of Electrum Gallery

Metalsmith ’89 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.