Metalsmith ’92 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

22 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1992 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Val Link, Matthew Sterling Morrow, Todd Zeilinger, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

National Student Sterling Design Competition

Yale Club, New York City

May 22, 1991

Tiffany's, New York City

July 8 - 22, 1991

by Anne Crowley Tom

One would expect that a national student sterling design competition would reflect leading-edge design from art and design schools and university art departments nationwide. In a sampling of work students felt strong enough to enter, we should see the "hottest" silver design by this creative generation. Unfortunately, this competition did not fully represent explorations in sterling among student designers. Despite 114 entries from over 30 colleges and universities, participation was spotty, with the conspicuous absence of many art departments where holloware is being done.

The stated objective of the National Student Sterling Design Competition was to challenge student designer/craftspeople to combine design and craftsmanship in flatware, holloware, jewelry, fine art and sculpture, resulting in innovative and trendsetting ideas. Design, function and craftsmanship, equally weighed, were the key criteria of the judges. While some of the winning pieces were outstanding, many of the entries were weak in construction, originality or practicality. And while much here was refreshing, several of the most original designs submitted as slides and drawings fell apart technically in execution.

The major sponsors of the competition were Coeur d'Alene Mines Corporation and Silver Trust International, a marketing organization founded by a group of leading mining companies. Judges were Ulysses Dietz, Curator of Decorative Arts at the Newark Museum; Robert Mehlmann, Instructor in Decorative Arts at New York University Graduate School; Jeanne V. Sloane, Vice President and Silver Specialist at Christie's, New York; and James McConnaughy, Vice President, S.J. Shrubsole Corporation, antique and American silver dealers. Judging took place at the Yale Club on May 22; the work of the finalists - 10 award winners, best flatware entry and nine selected entries - was on exhibit at Tiffany's in July. Out of these 20 prizewinners, only three were jewelry, the rest flatware and holloware; none were pure fine art or sculpture, although one piece of jewelry, a brooch, was part of a sculpture. Materials other than sterling were permitted, but most of the designs were exclusively sterling. The bulk of the pieces in the show carried on established design trends of the 20th century. Shape, line and even surface design generally derived from function in the Modernist tradition. Many of the principals of the design revolution that started in the mid-1930s under the canon of Modernism and continued through the mid- I 960s (functionalism, reductivist esthetics, avoidance of applied decoration - from the rigidity of the International Style, through the softening of streamlining and biomorphism, through post-war Modernism) still dominate this body of work by students of the 1990s. In addition, the influence of trends in the craft movement since the mid-1960s was evident.

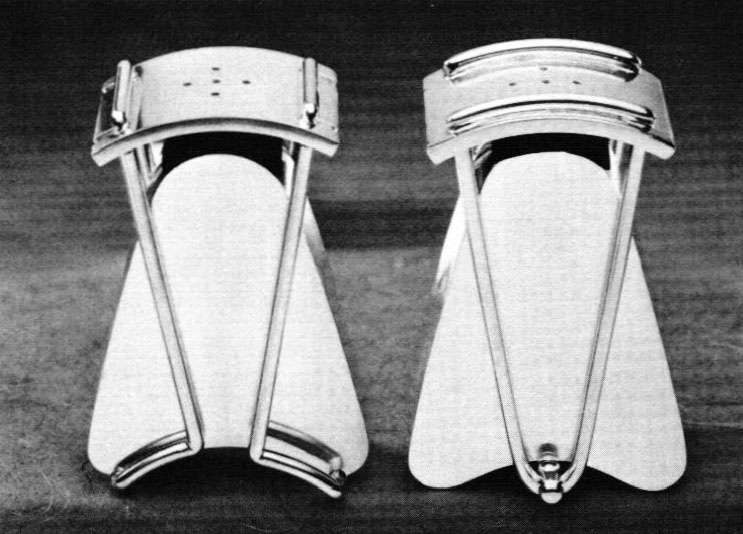

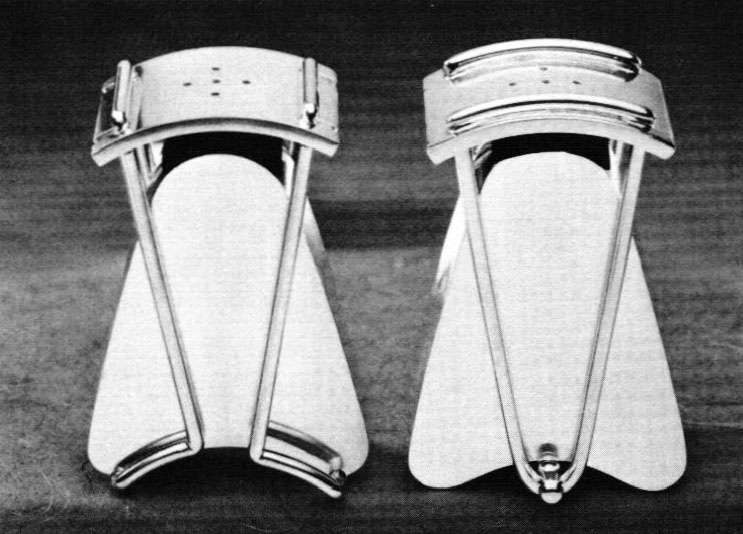

Among the prizewinners, design generally derived from function according to the esthetic first delineated by the Bauhaus. In may cases, even the surface design derived from function. Humor is also a strong component. This year's first-prize winner, a pitcher by Matthew Sterling Morrow (Texas Tech University), emphasizes the long, flowing curve of post-war Modernism, typified by Le Corbusier's architecture. The handle supports and lilts the base up with a graceful buoyancy that verges on humor in an off-beat approach to balance. Handle and lip merge as a continuous surface, resulting in organic unity. Qualities of minimalism, a resemblance to the smooth, upward-gesturing sculpture of Brancusi and biomorphic shapes of Arp root it in pre-war and post-war design. Second-prize winner salt-and-pepper shakers by Todd Zellinger (Center for Creative Studies, Detroit) reflect modified 1930s streamlining with its banded horizontal lines, rounded corners and masking of how parts connect. The originality of approach to function and derivation of the design from function is particularly strong here. The only applied surface design is the bands, part of the construction of the mechanism for filling the shakers. The hinged tops make it possible to refill without the nuisance of removing a cork or unscrewing the tops.

The resemblance of their shape to machine parts and ties to industrial design also characterized the honorable-mention necklace by Jennifer Tarentino (The University of the Arts, Philadelphia), a well-crafted and balanced 31″ chain of interconnected geometric shapes embellished with contrasting onyx and silver beads. However skillful the technique, this piece left me only with the chill of technology. Similarly, a pair of candlesticks that won fourth prize for Josephine Jacobsmeyer (Rochester Institute of Technology), Post-Modern in concept, appear to be assembled from scrap metal. I found the cut-out assemblage of bent rectangles and disks connected by legs of bent rods disconcerting in sterling, and lacking the unity and harmony of parts to back up its originality. Here surface design is applied, decorative and repetitive in the idiom of the pattern and decoration movement of the eighties. The inscribed squiggle with mini-squares and applied balls is part of the attempt at whimsy not usually associated with fine silver, but neither is it very interesting.

In other pieces, such as third-prize winner, a two-piece silent butler by Jean M. Graham (Mohave Community College), surface design was also decorative. A cerebral piece, in which etched Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols, echoed in planes of triangles and angular shapes, presented a narrative challenge, took a risk in its choice of objects to interpret. It is comprised of sweeping, dynamic shapes and lines, which render movement to match the brisk pace of its function - to quickly sweep away the after-meal remnants.

Another witty use for sterling silver was fifth-prize filigree basket by Aline Gittleman (Washington University School of Fine Art). Like many craft objects of the past 25 years, it draws upon non-Western art, referring to and defying the tradition of fine filigree by using silver as straw. A light, airy and rustic effect is achieved by leaving it white and unpolished, appropriate to the surprise contrast of primitive designs in an elegant material. The surface design is functional, serving as the structure of the bowl. The upper row of the design/structure consists of interconnected Picasso-like masks created by bent silver "reeds," and the lower a row of suns in various stages of rising and setting. Surface design and function also interfaced in the special flatware prize-winning fish slicer and fork by Julia Woodman (Georgia State University). The crisscross of the fish scale handles serves not only to introduce humor but also to strengthen construction. The metalworking skills represented here are impressive. The contrast of black and white to create negative and positive space, lends gracefulness and prevents the potential monotony of solid sterling handles.

A three-piece coffee/tea set, a selected entry by last year's first-prize winner, Beverly Auerback (Georgia State University) was well crafted but overdesigned. Rebecca Dworak (San Diego State University) deserves credit for the boldest design among the winners. Her bagel-shaped salt-and-pepper shakers of sterling, copper and slate hang precariously from an antler-shaped stand. While having to pass not just the salt, but the stand as well, defies my practical taste, their reference to the ancient ceremonial aspects of salt as a status condiment adds another dimension. Less exciting than last year's flatware winners, but worthy of honorable mention, is a three-piece flatware setting by Cindy Gibson (Rochester Institute of Technology) and selected entry three-piece sterling silver and copper flatware set by Amy Linn (Iowa State University College of Design), which safely continue the tradition of Scandinavian flatware with their predominant oblique angles. The only other neckpiece to place was honorable mention sterling, copper, and nickel neckpiece by Elise Worman (University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee) with its elaborate question of weights and counterweights and size and relationship to the human form.

Formerly sponsored by the Sterling Silver Guild of America, the national student competition has been in existence in some form for 30 years. The first-prize winner of the first competition, Burr Sebrina, was hired upon graduation to be Gorham's head designer. A prize from the student competition in one's portfolio has been considered a career asset. Metalsmith teachers who responded to the call for entries often were previous winners who have benefitted from one of the few opportunities for recognition in the field. In recent years, however, there has been little interest on the part of the silver manufacturers in the annual student designs. While the 1990 special flatware prizewinner's design was highly original, beautiful, and conducive to reproduction, the artist had no positive response from the multitude of silver flatware companies to whom he offered the design. This may discourage participation.

On the other hand, a prominent silversmith to whom the issue of participation was posed indicated that he felt the commercial nature of the competition discourages many student designers. He states, "'Design competition' is a terribly ambiguous term. Is it a competition for creativity or for acceptance by the industry?" In his experience, the sponsors of design competitions generally aren't clear as to what they want. "Is the challenge to be 'marketable' or exploratory?" he asks, adding "Some of the stronger programs such as Cranbrook and New Paltz are much more oriented towards the creative field and less of the work done there is in sterling for this reason. The support for sterling comes primarily from the commercial arena."

More attention by sterling manufacturers to student designs and more recognition by American museums to contemporary studio silver as an art form might stimulate broader and bolder participation in this competition.

Anne Crowley Tom is a freelance writer living in Manhattan.

Colette Narrative Enamel Jewelry

Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, MA

June 1 - July 31, 1991

by Susan Barahal

Colette's enameled jewelry is masterfully crafted and rich with symbols. The intricate cloisonné pattern of animals, objects and hieroglyphs in surrealistic montages seem to be attempts at capturing subconscious feelings. One is intrigued by the enigmatic images and captivated by the meticulous craftsmanship. Colette's recent work has been influenced by a bout with meningitis. From her hospital bed, all she could see were the room's white walls and the blue sky through the window. While recuperating, she conceptualized the "Ideogram" series. The predominant colors are hospital whites, sky blue, blood reds, grays and black. The images and symbols are haunting. We see cats wrapped in burial cloths and bound with cloisonné wire, the end of which is in the mouth of a bird of prey. Racoon-tailed cats stalk, red hearts engorge, nooses prevail and hourglasses in black and white remind us that time is measured.

The bezel-set edges of the enamels are asymmetrically curved. The bezels are either fine silver or 24k gold and are often engraved or stamped with the artist's personal hieroglyphs and enhanced by stone. She finds that commercially made bezel and cloisonné wire are too limiting and prefers to make her own. She draws or pulls the wires to the desired gauge. The bezels can be made with a wide surface, allowing room for engraving. Conversely, the cloisonné wire can be drawn to a much thinner gauge than is commercially available, enabling the artist to make fine line bends and turns. Examples of this are seen in the spiral heiroglyphs, the bird's tail feathers and the cat's toes.

Her skill in enameling is unsurpassed. Cloisonnéd sections are not merely filled with color but are shaded and modeled to give volume and depth. Transparent enamels are used alongside opalescents, and bits of gold and silver foil are placed under colors for a shimmering effect, To achieve gradations of shading, such as subtle nuances of white, numerous firings are required. It is not unusual for a piece to have as many as 25 firings.

Although traditional cloisonné surfaces are smooth and level, Colette's pieces are worked in high relief. Some surfaces are interrupted by 24k gold-lined, embossed depressions and craterlike punctures. This three-dimensionality complements the illusion of depth achieved by painterly shading and the use of textured foils. The choice of stones and certain design elements also contribute to the sculptural quality of the pieces. Bullet-shaped stones are bezel-set to protrude from their surrounding space, and bulbous baroque pearls in shades of white, blue and gray seem to bulge out of their bezels. Three-dimensional gold and silver forms dangle from neckpieces and hieroglyphs are deeply incised and appliquéd in relief on wide-cuff bracelets.

"Pictogram", a later series, groups many separate images into one wearable painting. Many of the symbols from the earlier "Ideogram" series persist, but there is a greater sense of optimism. The word "yes" is written clearly, the all-knowing and protective eye is present and hand shapes are repeated and prominent, perhaps affirming the efficacy of the craftsperson. The colors are more jewel-like and vibrant than in the "Ideogram" series.

Colette's enamels stymie one's ability to analyze their meaning with any certitude. Highly personal symbols and dreamlike presentations of subconscious thoughts are coupled with exquisitely crafted artistry, captivating and compelling the viewer to revisit these mysterious jewels.

Susan Barahal is the decorative arts editor for Art New England and teaches art in the Boston area.

Nine Japanese Jewelers

Jewelerswek Galerie, Washington, C.C.

April 25 - May 16, 1991

by Gretchen Raber

The Japanese metal tradition is one of practiced perfection. Oriental experimentation with alloys and surface ornament, a cultural and philosophical mindset of concentration and focus, allows for deeply controlled and abstracted expressions of nature. There is frequently a juxtaposition of contrasts to achieve harmony and balance. Here, this notion could be distilled into the seemingly contradictory idea of heaviness being light.

The work of Aya Nakayama expresses this concept through thick, though quite weightless lacquered rods. Powerfully tied to her cultural roots, the material is lacquered rattan in cinnabar red. Bold rod-shapes rise and twist, creating volumes of negative space. Proportion, craftsmanship and materials differentiate the oriental quality of these pieces from related European work, like that of Johanna Hess-Dahm. Nakayama's concern with findings and ingenious closings are not a priority as they are with her European counterpart. Nakayama's work, though pristinely crafted, does not have the industrial look so endemic of the bent tubes and rods of the Europeans. Conversely, Nakayama's deep red lacquer forms generate a sensual, tactile response.

Yasuki Hiramatsu's electroformed monuments to crumpled paper are witty and imposing. The bulky, cumbersome arm-ornament rises approximately six inches, its physical lightness a contradiction. These forms, in contrast to Western electroforming, are less concerned with technology than the freshness of the substrate. The core condition is emphasized and preserved. The surfaces reflect a raw immediacy, a result of the process. However, when he mimics Caroline Broadhead's headpieces, substituting silver wire for nylon, one has to ask, "Why?"

Traditional techniques are used by Erico Nagai to assemble hollow-tube "bars," incorporating surfaces of black and gold, cinnabar red and gold. The colors and patterns evoke the elaborate, lacquered object tradition of the Edo Period in Japan.

Some of the strongest references to Japanese metal tradition in the exhibit belong to Okinari Kurakawa. His titanium-disk neck ornaments, although rooted conceptually in European and Dutch forms, i.e., Coen Mulder, have an aggressive bladelike quality reminiscent of the Japanese martial metal and sword tradition. These disks have refined craftsmanship and restrained ornamentation. Visually, the edges are subtly dangerous. Although not swords that exude the spirit of the warrior, their contrast and balance manifests the spirit of the materials. Kurokawa's ring series relates closely to contemporary European art metal, but is less subtle. It is more of not what you say, but how you say it.

Etsuko Sonobe conceptually follows Caroline Broadhead's brush technique. However, through the use of oriental-specific materials, she emerges with more individual expression than some of her exhibiting colleagues. The grass bristles are a rough counterpoint to the elegant and refined channels that are created by Sonobe. They are more in scale and harmony with the body than their European references. In contrast, Wahei Izezawa shows no evolution from what appears to be largely Euro-tradition. Excellent craftsmanship and deceptively lightweight forms are the work's strength.

The Familiar work of Hroko Sato Pijanowski provides a diagram of traditional oriental materials used with a basis in Eastern philosophy. In David La Plantz's new book, Jewelry/Metalwork 1991 Survey, Hiroko relates that "Philosophies of Zen and the Haiku of the 17th-century Master Basho provide an intellectual framework within which we can express our own emotions through objects. These philosophies suggest that there is a unity and beauty in the universe that encompasses both man and the natural world." One must seek in materials, the intrinsic qualities that unify, the intellectual, the physical and the spiritual. The mizuhiki shapes of Hiroko are this unity of the humble material with the intellectual sophistication of form. The individual element evolves into a new idea. It is the contrast of balance of the precious and mundane, the heaviness of being light.

Gretchen Raber is a goldsmith and architectural metals designer living in Alexandria, VA.

Val Link & Graduates A Platinum Retrospective

Boardwalk Gallery Goldsmiths, Houston, TX

May 1 - 31, 1991

by Beverly Penn

In the spirit of encouraging ties between academic metalsmithing and the retail world, the Boardwalk Gallery Goldsmiths and Val Link, head of the University of Houston's jewelry/metalsmithing department, assembled the work of 21 alumni who had graduated from Link's program over the past 20 years. Among the more than 100 pieces compacted into this bright, highly visible space were objects of every possible format (jewelry, holloware, flatware, tools, containers, containers with removable jewelry, jewelry with movable containers) and intention (artwork, production work, crafts, design prototypes, one-of-a-kind, one-of-a-series, series of one, one of many). In the retail context of a mall, such a broad range of objects and sensibilities seemed tentative and experimental, though BGG's initiative in supporting more conceptual work is commendable. From an academic standpoint, the diversity of this exhibition represents the dilemma that challenges American academic metalsmithing as a whole: do efforts to encompass each and every material, format and technical procedure result in conceptual thinness? Do we pay a price for having it all?

The featured work of Val Link was a selection of pieces from his productive 25-year career. Technically superb, his knives, jewelry, vessels and objects reveal a sense of humor, ingenuity and a joy of making. The two awards of merit were garnered by Diane Falkenhagen and So-Im Kim, in jewelry and holloware respectively. Falkenhagen's lyrical brooches are podlike chunla of white Corian embellished with colorful fragments and sinuous metal lines. Also singled out were Kim's pristine vessels and flatware designs, forms that extend function far into the realm of sculpture. Other work included some projectlike academic work, a variety of fine and production jewelry, and some highpoints of individual expression, for example, in the work of Lee Roeder and Deborah Jemmott. Ken Bova's colorful jewelry is the funky, folky variety that razzle-dazzles, wows and charms. Fabricated from a seemingly endless list of precious and non-precious materials, his jewelry "cut-outs" are fat, graphic and theatrical. Though Bova's imagery - hands, hearts, dogs, spirals - has been heavily overused by artists and designers this past decade, there is a sincerity in his direct, nontechnical handling of materials. The pieces are clearly fun-to-wear, fantastic ornaments. Tami Kegley, working collaboratively with Charles Kegley, poises her layered, topographical brooches of precious stones and metals atop tiny, delicately turned bobs of exotic hardwood. The work is carefully made, and one is immediately drawn to the fine craftsmanship, material presence and logic.

Art critic Peter Dormer once wrote that "(T)here is… another role for the contemporary jeweler - that of artist. The word artist is overused and it should be employed rarely and only for the handful of individuals who are able to create metaphors that give us a new way of seeing the world. Most jewelry does not attempt or succeed in altering our perception. Occasionally someone comes along who can use jewelry to make a commentary on the world." The brooches of Mary Ann Papanek-Miller are melancholy, unpretentious statements that identify her concern for a range of social and political situations. Overlapping drawn images and decals float in frozen layers of transparent enamel on the square, etched, silver backplate. Other carved three-dimensional figures or animals of charmlike scale are mounted simply and directly to the picture plane, poised to eyeball the scenario to which they are simultaneously observers and participants. Her enumerated sequence of collaged images entitled Morning Dove, Morning: Disguise, Morning Jog strongly evokes a narrative. The square format alludes to common methods by which narratives are often revealed, such as the photographic image, the book or even television. The work, however, is not merely revealing or didactic. What is compelling about this jewelry is Papanek-Miller's metaphoric use of visual structure: she extracts noun images from the logical sequence of a plot structure, and subsequently disposes them randomly within the tiny picture plane, much in the same way that the Surrealists used the irrational as a form of visual structure. As viewers, we feel urged to decipher, but the pieces remain poignant questions.

Storytelling predates all other forms of self-expression. One of the primary objectives of narratives is to relay a message, to tell a story. Sandra Zilker's mixed-media brooches also suggest a narrative, but their whimsical character makes them more like visual limericks than Papanek-Miller's pensive vignettes. Zilker employs the sensitive exaggeration of caricature in her pairing of subjects in unlikely ways. Her 2⅛" square brooch Food and Forks: Carrot is a group of miniature silver implements and food piled carefully on a smallish, square gesture of a plate, which is itself anchored to an expressive chunk of material (Corian) simulating a cutting board. The three metal forks are poised, ready for action, over the tiny captured carrot. The piece is a humorous and irrational representation of an otherwise logical combination. Often, art in this spirit of whimsy and exaggeration can melt quickly into the realm of one-liner-dom. But Zilker's vision in not merely about amusement: she engages our fantasy, in the manner of Lewis Carroll, using humor as the foil for larger, more profound issues.

While no particular "school of thought" was apparent (some thoughtful work, yes, but no lingering ideologies of intellectual stamp), the general level of technical expertise and design ability hinted at more than capable directions is certainly evidence of a skilled and confident educator.

Notes

Maria Teresa Carné, Fundació Caixa de Pensions, Joieria Europea Contemporània (Barcelona: Fundació Caixa de Pensions, 1987), pp. 68-71.

Paul Schimmel, American Narrative/Story Art: 1967-1977 (Houston: Contemporary Art Museum, 1977), p. 4

Beverly Penn is an artist at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos, TX.

The Metal Vessel

August 1 - 31, 1991

Artworks Gallery, Seattle, WA

by William Baran-Mickle

Seattle was treated to a jewel-like introduction to the art of the metal vessel at Artworks Gallery, a commercial fine-craft gallery in the city's downtown gallery district. Inspired by a lecture and workshop given by Helen Shirk, the gallery enthusiastically embraced the "new" art form with a showcase of some of the best metalsmiths in the country working with the vessel form. The two-year-old Seattle Metals Guild, formed to acknowledge the many talented jewelers and metalsmiths who have settled in the Northwest, was the influence behind the scenes, having invited Shirk to lecture.

In a community that has embraced the glass vessel - due to the Pilchuck Glass Center's influence - a small, survey-style exhibition of contemporary metal vessels was a good way to introduce a parallel art form. While most of the artists were well known and respected, in such an exhibition, where one object represents one artist, it was not depth but the artist's choice of object that was of value. In this area there were some surprises worth discussing.

Randy Long's Lorenzetti Lily Vasewas a departure from her early, theatrically based holloware. Lily Vase sirs more stolid, compact and centered. This vessel relates more to her jewelry of recent years, which is based on historical references. Straightforwardly simple, this copper bottle form lifts up and radiates outward with two angled arches extending above the lipless neck. The title, moreover, indicates a relationship in attitude to the Sienese brothers, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, of the early Trecento. This would indeed be a grand abstraction. It seems to echo Pietro's detailed elegance with his ground-breaking spatial constructions, wonderful accents of vaulted arches, tile floors and checkered textiles, and Ambrogio's earthy solidity. Furthermore, the vase is thoroughly painted in acrylic over gesso. The overall body is a mint green and the arch forms are banded with a gradation of black and white. While this practice of painting the metal's surface is not new, it remains unusual and holds the promise of a rich, added dimension for esthetic inquiry.

Another metalsmith who used a historic reference took a more stylized approach. Leonard Urso's Gift offers no escape from the fully reclined, static figure centered at the bottom of this elongated bowl. The reference is decidedly Egyptian, reminiscent of mummy and mask forms. As with the arches of Long's vase, this figure, in high relief, is flanked by deep, angled sides covered with a systematic machine texture that creates a rarified atmosphere, brilliant and radiant like a rock garden rendered in fine silver. The figure is pared to its barest essentials, arms folded over chest, legs diminishing into the bowl, as does the head. This form of stylization has been a common treatment in Urso's gold jewelry and works well on this scale. The tide might indicate the gift to be a vessel for the "splendid journey" of spirit life after, or as a door to a past. Both of these mysterious indications hold a common intrigue in our society.

Tom Muir and Michael Tom sent work equally useless as functional holloware, existing instead for the temporal experience they evoke. They speak to opposite sides of the same spectrum. Muir's Silver Vessel celebrates the refined machine esthetic of the last century, where layers and slices of ambiguous forms collect upon the central vessel along with organic accumulations. The coexistence of these disparate elements seems to create a sort of ecosystem. Tom's Hollow Shell of a Stone, on the other hand, reflects on the condition of the earth and the overtones of society's spiritual decline and cultural upheaval. The stone breaks up like an egg, and is partially staked in a desperate attempt to hold the rock together. He successfully creates the feeling of weight and lightness simultaneously.

It is always a pleasure to see fine examples of holloware by well-known metalsmiths. The remaining exhibitors were: Candace Beardslee, Pat Flynn, Tom Markusen, John Marshall, Claire Sanford, Helen Shirk and Debra Stoner.

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer living near Rochester, NY.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Metalsmith ’91 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

Metalsmith ’83 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Metalwork

Knifemaker’s Art Exhibition

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.