Metalsmith ’93 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

32 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1993 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Ruudt Peters, Jamie Bennett, Albert Paley, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Borne with a Silver Spoon

Sybaris Gallery

Royal Oak, Michigan

March 25 - May 1, 1993

by Kathy Buszkiewicz and JoEllen Stevens

Consider an ordinary object which each of us regularly handles in daily ritual. Its function is related to that which is life-sustaining, yet its presence is life-enhancing. The diurnal utilitarianism of conveying food to the mouth, especially in our sensually anesthetized society, may have obscured the spoon's rich history and significance as a primal tool. At your next meal, hunger for more from your spoon.

A traveling exhibition and sale of contemporary American spoons entitled Borne with a Silver Spoon entices you to ruminate on the phenomena of the spoon more extensively. The exhibit can be viewed in eight cities from November 1992 to December 1993.*

Curated and organized by Rosanne Raab Associates, Borne with a Silver Spoon originated with an invitation to over 40 artists to submit "A unique or limited edition design of the spoon in either a functional or sculptural form". Intended to appeal to collectors, participating artists agreed to replace each spoon with a comparable piece when a spoon sold, consequently, the exhibit may vary from venue to venue. This review reflects the exhibit during its April 1993 display at Sybaris Gallery, Royal Oak, Michigan.

A traveling exhibition and sale is an opportunity for artist, gallery, and collector to buy and sell. A book of postcards accompanies the exhibit, showcasing thirty-seven of the forty-five artists represented. The cover of the book describes Borne with a Silver Spoon as "the premier collection of functional and sculptural spoon designs" as well as "representing the art of the metalsmith in the 20th century". The format of this "collection" however raised some questions.

When metalsmiths previously making disparate objects consider an object such as a spoon for an object defined show, can a sale/exhibit evenly reflect the diversity and scope of metalsmiths making a particular object today?

Does an exhibit with highly marketable aspects encourage a middle comfort zone of "designed for sale items" and discourage the adventurous to explore new territory?

Should an object oriented show promote a new way of perceiving that object? Can it refine traditional and define contemporary form both for the artist and the public?

The scope of the exhibit included approximately 148 pieces including single spoons, serving sets, and multi-spoon sets for specific foods or functions. The artists approached the spoon in a variety of genres.

Exploring the usually ignored but highly sensual aspects of the spoon, Lin Stanionis's voluptuous serving set seems to writhe in eager anticipation of some elaborate feast. The pieces are visceral forms with suggestive foreskin pulling back from the tongue-shaped bowls, edges rolled with thick lips. The stem snakes to a coil then stretches to end in a threatening ringed rattler's tip. Her four teaspoons of sterling, mycarta, and lacquered wood are mysteriously hued along the segmented stems in green, mauve, red, and grey. The hollow bowls are protected by their nutlike textured shells. When they are turned over, genital forms are exposed in the recesses. These teaspoons stir quire an arousing cup and redefine the term "oral sex" through stimulating the enjoyment of eating.

Continuing to arouse the senses is a beverage ladle by Robyn Nichols. Large in scale, Hibiscus makes it presence known and boasts a showy floral bowl which is held by a severe handle. The juxtaposition of organic rhythms and geometric curves jolt the fragile form seduced into silver and forever sentenced to serve beverages at cocktail parties. The ladle is finely crafted as are all six of her pieces in the show.

Laughter engages the senses in Nichols's humorous Humpty Dumpty baby spoon. The mechanics playfully provide a teetering character with text that exclaims "oops". There is a correctness of scale and a quality that will earn the spoon the rank of heirloom treasure.

As objects to be handled, spoons can be physically playful through mechanistic qualities or they may simply suggest a visual playfulness. Brigid O'Hanrahan's Twig, Rattle, Spiral, and Bead exhibit a consideration of the spoon's duration in an active hand. They are to be shaken, turned, fingered, and twirled as musical accompaniment to the playing with one's food. Joy Raskin's Moving Bridge has a wonderful motion that clanks the bowl from end to end. Although limited in its function, it addresses the concept of conveyance while possessing a toy like characteristic. Arlene Fisch's collection of spoons plays visually with her name while being reminiscent of the immediacy and playfulness of the utensils made by Alexander Calder in the mid 20th century.

A dozen metalsmiths in this show can be categorized as directing their spoons purely towards function with the addition of good design. Most noteworthy was Robert Davis's three spoons possessing fine craftsmanship and well considered details. The spoons all weigh well in the hand, scale suits the function, and the bowl designs are interesting without sacrificing their main purpose. Yet many other spoons in the exhibit fail in terms of function and when in the hand: notably Boris Bally's Zulu Serving Set, Duane Maktima's Pueblo V-Deco spoon, and Leonard Urso's Figure Spoons I and II. To pick up an object that was designed to perform a specific task and have it roll or flip due to a balance problem decries a lack of functional considerations and this sleight is peculiar when it comes from a metalsmithing community steeped in the history of making such items.

The very form of the spoon can visually and physically deny its function. Sue Amendolara's Dessert Mint Spoons are an example. Their sensuous forms deceive; appearing to be lightweight, they are cast and heavy. The title suggests a pleasant function, to serve a refreshing mint for dessert. Yet the pointed bowls contradict the title and appear ready to spear and stab.

The spoon's function is enhanced and questioned in O'Hanrahan's Pencil spoon. How many times does one sketch or write while waiting for service during a meal? This spoon captures those flashes of creative inspiration before they can escape from the tabletop. Of course, one must be prepared to buy a box of #2 pencils. Raskin's Thermometer spoon humorously suggests taking the temperature of the liquid prior to consumption to prevent a scalded mouth, or taking one's own alter eating a "hot" meal. Although tongue-in-cheek, the dual purpose of these pieces challenges one to perceive a spoon's function in various ways.

David Bacharacht works celebrate the spoon through non-function. They elicit a spoon-like quality with their shallow bowls and palm size scale and contain a reference to vessels with their woven forms. They are vestigial reminders of ritual and ceremony.

Early spoons were probably shells and subsequently the materials evolved to bone, horn, wood, and eventually metal. The object remains a tool that contemporary humans share with their ancestors and is an appropriate vehicle to reflect current tastes and concerns. The calling up of derivative references such as the spirals and shield shapes of Robert Farrell, Boris Bally's titles - Maori and Zulu, and the surfaces of Gary Noffke are examples of contemporary artists appropriating motifs and styles from other cultures. However, without addressing or understanding the source of those references, artists fall short of their responsibility. Many seem to have a fascination with borrowing from other cultures as if our own is devoid of iconography or rituals. That we do indeed possess our own iconography is evidenced by John Cogswell's Baby and Toddler spoons which remind us of our culture's ritual of giving baby spoons as gifts. He has quite suitably combined the characteristics cited in the exhibition's title with the spoon's material and function. Additionally, some thoughtful reflections on our culture are exemplified by the concrete material used in Paved by Bally, Susan Hamlet's symbolic imagery, and the sensuous forms and scrumptious surfaces of Stanionis's work.

So how can a spoon conceptually address our culture in other ways? Fred Woell provocatively serves with his witty and insightful spoons. They position themselves within the souvenir spoon genre which commemorates events, places, and people. Woell successfully uses the format as cultural commentary with such titles as Parting Shots, Running on Empty, and Take Out America: food for thought.

Moving from the table and the collector's rack, Myra Mimlitch-Gray's work proceeds to the wall. Her three pieces use the spoon as an instrument to speak about the feminine and romance while they contain both phallic and vaginal forms. She chooses the correct spoon, romantic with its flowers and scrolls, and splits it down the middle into a womb or heart shaped container with dark interiors. The splitting is a defiant act against role, objectification, and traditional ideas about spoons.

The human figure has paraded along spoon handles throughout history, from ancient Egyptian cosmetic to 16th century Venetian to caddy, apostle, and souvenir spoons. This tradition continues with nearly a half dozen artists in the show. Conspicuous among this group are Randy Long's Adam and Eve. This tense pair, despite their natural state, bear no other references to the mythical couple of the tide. The bowls are ovoid, shallow and rimmed. What do they intend to serve, to whom, and on what occasion? The tide presupposes more visually challenging clues or suggestions of specific use or ritual. With less, they are anonymous and obscure. Adam and Eve stylized realism places them in the liturgical stereotype of the recent past, yet they refuse to synchronize with the plethora of contemporary figural language common in Robly Glover's Bird Girl or Nancy Slagle's Figure spoons.

While many of the artists approached the spoon primarily as an object to be designed, it is thought-provoking that there is not more provocative thought given to original design. Some spoons are inevitably splashed with "designy" patterns consisting of triangles, spirals, dots, zigzags, and squiggles. Here the spoon is relegated to a mere device bearing the generic motifs in vogue. Furthermore, eight artists expose the phenomena privy to all metalsmiths - an inordinate love of one's dapping block, producing the proverbial "melon-baller".

However, there is a handful of wonderfully designed pieces that command recognition. Among these, David Peterson's intriguing serving spoons evoke the symmetry and structural nature of skeletal form. These beautifully conceived and well executed pieces are as harmoniously arranged and as functionally capable as actual human limbs. Likewise, Susan Hamlet's two enigmatic spoons are admirable. They are detailed with iconography that is perhaps intensely personal yet allows for individual introspection.

The rich history of the spoon stimulates a palate of possibilities that can push the parameters of interpretation. With a show that presents such a familiar object, it is paramount that the artist challenge the viewer rather than spoon feed. Borne with a Silver Spoon offers both.

*At the writing of this review, more exhibition sites may be added extending the show through Spring 1994. For an exhibition schedule and accompanying postcard book of Borne with a Silver Spoon contact Rosanne Raab Associates, New York, NY.

Kathy Buszkiewicz is a metalsmith and professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art. JoEllen Stevens is a metalsmith residing in Cleveland, Ohio.

Ruudt Peters

Jewelerswerk Gallery

Washington, D.C.

April 15 - May 16, 1993

by Gail Brown

Ruudt Peters, Dutch sculptor and goldsmith, makes jewelry to give physical form to the complexity of human relationships. He explores the complex nature of intimacy, celebrating moments that are personally and historically significant, focusing little on decorative adornment. The exhibit at Jewelerswerk Gallery displays four series of work, providing insight into Peters's vocabulary and aesthetic solutions.

In Symbolen, a group of bracelets from 1986, Peters focuses on the space within the form. The bracelets capture the wrist in linear forms of gilded brass made from flattened rods. We are mindful of the intimacy of the union: the encircled, gently squeezed arm is as important as its cage. In Spear Cloud, and Capital, the artist communicates the line with whimsy and élan.

In 1988, Peters made brooches "DEDICATED TO" six friends and their various connections to his responses to an Egyptian trip. The darkly patinaed, brass, flattened domes attach to the body by a hidden stickpin. Each has a small cutout area which echoes the simplicity seen in the Symbolen. Water, Bridge, and Petra invite curiosity about the unseen interior space.

The Interno series of brooches have thick silver figures enticing one to peer inside large openings which silhouette the simple, elegant outer forms. Yet one discovers that the pieces are only frameworks which surround nothing; one looks through the hole to see only the body of the wearer. Others in the series reference Renaissance architecture. Slices of sleek domes encase interiors rich with decorative elements: jewels and cameos mounted within. The walls serve to surround the secret accessible only to the intent viewer, both hiding and inviting one to explore the enclosed secrets, referring to both myth and history.

Brooch Antholin is an eight-sided, faceted, silver dome whose interior displays vertical, patinaed walls, patterned with cutouts which play with light and shadow. Exquisite workmanship is a given: the delicacy of the riveting juxtaposes with the strength of the well proportioned, symmetrical form. This piece celebrates the church of St. Anthony in England, with creative inversion wherein the windows on the inside reflect each other, thus provoking our own self-examination.

Brooch Melk 2 celebrates both the richness of our interior selves and the rococo excess of an Austrian Baroque monastery. A pickled silver, seven sided, open cupola rings an interior wall whose blackened surface is adorned with overlapping "charms" of oak leaves, crowns wreaths and harps. There is a provocative tension between the external simplicity and the lush, ornate interior. An exploration of the "hole", in the one form of jewelry which does not need an opening for wear is intriguing. Mystery is discoverable and accessible.

Brooch Tempietto, an open, wide washed silver form, offers a view through a series of floors layered with arched and circular perforations. Celebrating Bramante's temple in Rome, the cutouts reference the floor plans of churches, one built upon the other. The stratification recalls both general and personal history. The patterning focuses attention on the intricate spaces and their sense of promise.

Structures with a rich color range become vessels of ceremonial formality in the Passio series of silver pendants from 1992. They express a passion for life and death, eroticism and drama, and reference figures from history, mythology and Christian tradition. The exploration of interior/exterior has become a more subtle inquiry; viewers are lured by glimpses of objects through well spaced, stranded links, loosely meshed chains, or patterns of holes in the vessels themselves. Intimacy is enhanced by the tactile pleasure of the moving, suspended form against the body. There are other surprises: perilously balanced pebbles clustered around the objects and gems set inside the open containers. The pendant can be precariously angled or formally upright.

In Dionysus, a patinaed silver amphora, multiple strands of tiny, carved, purple garnet beads hang in heavy lines skirting the form. The ambrosia seems to flow as emotions are expressed freely. There is again, the opportunity for the unexpected: the vessel can float on the wine of garnet beads or all of the strings can be hidden inside for the wearer's private delectation.

Alexis is a persimmon-like form, whose gracefully faceted surface is emphasized with etched graffiti. The words celebrate the men important to the artist. Anticipating the unusual one lifts the bell-like shape revealing twenty five black stone and seven jade, carved hearts, each dangling from the linked chains. There is pleasure in deciphering the meaning of the different materials and who is signified by each. Yet one does not want all of the mysteries to be solved.

In 1992, Peters accepted a commission to design a balcony for an apartment complex to house émigrés in Amsterdam. Anticipating the interaction of the peoples, the artist collected emblems from the multiple cultures and combined them into a screen of new symbols . In Machiavelli he reintroduces these symbols as charms which dangle abundantly around a copper globe. The large sphere is dotted with tiny orbs and emphasizes the many individuals which make up the whole. Fragile strands of orange cotton thread connect the talismans to the ball to create the necklace. The tension between materials, forms, and ideas extends throughout human relationships. Peters validates the important role of the viewer/wearer as that of an accomplice, asserting the role of the wearer of adornment as a necessary accompaniment to the nature of jewelry.

Gail Brown is a writer on metals from Philadelphia.

Jamie Bennett: The Domestic Distance

The Clark Gallery

Lincoln, MA

April 27 - May 21, 1993

by Susan Barahal

Although metal hollowware is the subject of Jamie Bennett's recent show at the Clark Gallery in Lincoln, Massachusetts, there are actually only three metal objects on exhibit. The majority of works in the show entitled The Domestic Distance are oil paintings on paper. Each of these paintings depicts a sensuously modeled rendering of a pouring vessel.

Sketches and paintings have often been executed by the artist, and Bennett feels that his paintings reaffirm his interest in metalsmithing. The paintings exist as independent and powerful forces rather than primarily as preliminary studies. Indeed, each of the three vessels in the show is exhibited in conjunction with a companion painting and consequently both image and object are read as one piece.

The pairs are arranged so that the framed painting is to the left and slightly higher than the bottle which sits upon a wooden pedestal. The viewer visually unites the two and establishes interaction. A duet ensues a motionless pas de deux.

Bennett was inspired by book illustrations of 18th century Britannia metalware which, although elaborately designed and executed, were plate with silver and, therefore, affordable to people of average means.

Bennett's interest in and exploration of the vessel form is not without precedent. The new electroformed and enameled bottles are in keeping with and extensions of the inherent organic vessel forms of his 1988-89 brooch series, which were fabricated in the round. However, while allusions to nature were incorporated in the earlier pieces, these new paintings and three dimensional objects combine specific and deliberately arranged stylized stems, leaves and buds.

The tactile qualities of the thick impasto of paint into which Bennett incises and scrapes, echo the undulating surfaces of the equally painterly, enameled and electroformed copper vessels. These bottles betray the soft textures of the now transformed, original wax forms.

With this new work, the vessel form takes on an iconic significance likened to portraiture. Indeed, Bennett is intrigued that both body and vessel parts often share names, such as mouth, lip, neck and foot.

Bennett's recent tribute to the vessel, its use and our relationship to it, continues to affirm the form's inherent beauty. Furthermore, this exhibit helps to combat what the artist views as our culture's increasing emphasis on purely utilitarian containers, such as the ubiquitous tin can.

Susan Barahal is a principle of Barahal-Taylor Fine Arts in Boston and a frequent contributor to Metalsmith.

Albert Paley

Reggiani Gallery

New York, NY

January 28 - April 17, 1993

by Lanie Lee

To make an intimidating material such as steel appear pliable is no small feat, but it seems to come naturally for Albert Paley. In a solo exhibition at the Reggiani Light Gallery, which was a collaborative effort with the Peter Joseph gallery, Albert Paley's work of decorative furniture made from black steel and mixed media combined elements of the baroque, art nouveau, and modernism.

There were a few grand scale pieces that seemed more like monuments than decorative furniture because of their sheer volume (which probably has some connection to the public commissions that Paley has worked on in recent years). All the pieces were hand-forged mild steel (some pieces incorporated materials such as carved stone or wood as well as glass) configured into organic shapes and sharp-edged forms. Simple elements shifted into complex ones, and together they worked off one another into frenetic gestures. Every piece had twisting forms that created a sense of motion and growth, giving the illusion of perpetual movement.

Wave Mirror (1992), a massive piece, had an overall simple curvilinear design that allowed the separate forms to coalesce while maintaining their own shape and space. For instance, a large, circular vanity mirror was mounted onto a round steel frame, which had a few quirky shapes jutting from its perimeter. Considering the weight it had to support, the base was unobtrusive and tapered into curved legs that unified into an extension of the frame. Light colored Honduras mahogany carved into the shape of a wave, was set across the lower portion of the mirror as a ledge, adding motion to an otherwise static piece. Paley used the steel, mahogany, and glass, to produce sharp color and density contrasts, meshing the basic forms into an architectural seascape.

In contrast to the meditative quality of Wave Mirror, Presentation Table (1992) made from mild steel and carved slate had an ominous overtone. The table legs were spear shaped with spiraling relief work. Each leg had a hatchet form with thin tendrils on the top and bottom that wrapped around the spear like a vine, connecting the elements in a chaotic motion. The tabletop was a well guarded area, with pointed spear tips that extended beyond its four corners in a threatening manner. Tall Cabinet (1992), made from steel, brass and basswood, was a piece in which Paley escaped from the heavy handedness of the steel. Resembling a tree, the light-colored basswood cabinet was a tall, slender, octagon shaped trunk. Thin brass strips wrapped around the top and bottom of the cabinet, joining it to a stalky, organic appendage made of steel that subtly climbed up the side of the cabinet and became fully bloomed on top.

Perhaps the most appealing aspect to Paley's work is his ability to contort steel into objects that seem to defy the properties of the metal. Like a modern day alchemist, he seems able to convert materials into forms that convey a sense of nature's gestures. At times, there was an abundance of tension and energy that veered toward the chaotic, but it nevertheless successfully defined the affinity that the artist has with nature.

Lanie Lee is a writer and editor who lives in New York City.

Barbara Stutman: Plotting Our Progress

Galerie Elana Lee, Verre D'Art

Montreal, Quebec

April 27 - May 18, 1993

by Jenniefer Salahub

The press release stated that the exhibition was "… one woman's look at being female in today's world" and if I was prepared for the anger, the introspection, and even the humour of the theme, I was not at all prepared for the strong emotional response that the techniques themselves evoked. Nor was I ready for the confusion I felt as I contemplated wearing the highly charged objects that make up Plotting our Progress, an exhibition of sculptural jewellery by Barbara Stutman.

Stutman is an established Montreal metalsmith and her long fascination with applying textile techniques to metals has become a trademark. While she is quick to acknowledge the debt she owes to artists Arline Fisch and Mary Lee Hu (she studied with the latter) she also points out that knitting and crochet were an integral part of her upbringing and therefore the use of wire, rather than yarn, was not a totally foreign experience. This acceptance of a familiarity with traditional women's hand work becomes even more appropriate given the theme of this exhibition. She chooses techniques long associated with domesticity and the inculcation of feminine values in Western society; using these techniques to illustrate such controversial subject matter is brilliant. Stutman presents a veritable sampler of wearable social issues and every element - each bracelet, each necklace, and each brooch - exemplifies a multifaceted approach. The artist incorporates a variety of materials (silver, copper, bronze, magnetic wire, fossils, jade, eceteras), treatments (patinas and enamel paint), and techniques (knitting, crochet, spool-knitting and twining) in her works.

In Plotting our Progress Stutman has added a new twist, asking us to unravel the tangled web of information. In Power Accessory, a formidable studded copper bracelet, the physical strength of the medium is symbolically undermined by the hook and eye closure and the lacy quality of the knitted structure. The delicate appearance of the technique and its association with women's role within a domestic sphere is at odds with the notion of power, a traditional male attribute. Is this an accouterment of Wonder Woman or a controlling/constraining dog collar?

Stutman's works provoke a mixed response in the viewer. In Portrait of a Rape Victim and Dark Cloud from the Past the aesthetically beautiful and finely crafted works are in disarming incongruity with the harrowing subject matter. However, rage is displaced by wry humour in her series of witty tampon holders. Each vibrantly coloured and exotic spool-knitted container could easily be misread as a prom night corsage holder/vial symbolizing a young woman's coming of age. Nonetheless, in these brooches societal recognition is replaced by the actual event that marks a woman's entrance into puberty.

The whimsical composition of a pair of earrings, Maintaining the Status Quo, also invites a multivalent reading. Here the combination of familiar objects worked in an unexpected manner is reminiscent of the Pop Art aesthetic, however the subject matter is topical. In each earring a high heeled shoe is being engulfed (trampled?) by a boot. While I would like to read this image as a sign of progress (a rejection of the North American cult of beauty), the label belies this interpretation. Following a tangled path we return, once more, to the title of the exhibition. Indeed, how far have we progressed?

Jennifer Salahub is a textile historian and critic living in Montreal.

Pat Flynn

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, California

April 5 - May 1, 1993

by Matthew Kangas

Where does production end and art begin? Why is it no one questioned the serial technique of monumental Minimalist sculptors and yet many accuse jewelers of commercial repetition? Is a production piece "design" while a one-of-a-kind work automatically is "art"? These and other questions are raised by the work of Pat Flynn, a competent, talented artist who combines rough and fancy materials in jewelry of great beauty.

Instead of criticizing his sequential imagery of repeated forms, as did Debra Stoner in the Summer 1989 Metalsmith, why not see Flynn's work as a series of themes and variations, or as conceptual reconfigurations of a primary idea?

Iron nails were the uniting material, if not idea, amongst a dozen or so pins and brooches shown at Susan Cummins this spring. The fairly familiar cachet of rough and fine materials was explored with great invention, if not originality. William Harper recently used this combination in Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Haruspex (1990) but Flynn drops Harper's pinhead face and emphasizes the nail head as well as its length.

Spiral Nail Pin (#192) and Brooch (#191) wrap baroque gold thread around the vertical form adding white and yellow diamonds. The curve of Spiral Nail Pin suggests an intrauterine device and would look great on a pro-choice activist. More abrupt, Large Nail Diamond Pin (#193) adds diamonds to the lower side as well as up and down the front facet. Here the point of blunt material contrasts is more successful when restrained.

The rings wrapping a nail around a finger are supported by a wide gold band to better offset the crudity of the iron. #196 displays a blue opal on a gold halo and a floating opal on #195 is joined by a diamond at each end; a ruby teardrop informally sits to the side.

Although it is apparently a production item, a pair of earrings #180 recalls the solar system with a multi-colored mabe pearl surrounded by 12 diamonds that look like planets orbiting the sun. The flat gold supporting this miniature galaxy is irregularly edged on each clip.

A brooch #190 and a pin #176 flatten out the surface and provide a more two-dimensional, less sculptural image. The ridged top of #176 sits above a flat surface broken by a line running down to a ruby. A tiny earthquake fault line is suggested which symbolically may echo the geological origins of the stone. #190 also widens the surface, topping it with a boulder opal.

After more than a decade of his evolving signature style of clashing and unexpected materials, it will be interesting to watch Flynn's work in the current decade to see where it goes. Addressing many of the issues facing contemporary jewelers, he also faces the risk of mining too deeply his original inspirations and turning them into tired conventions. But then, most craft artists only have one idea per decade.

In Mill Valley, each work seemed freshly and individually conceived but, after thoroughly excavating these diamonds in the rough, Flynn could further explore, color, scale, and a content which makes greater symbolic reference in order to lend a conceptual richness which will match his impressive material mastery.

Matthew Kangas, a former Renwick Fellow in American Crafts, is a Seattle art critic and curator who writes for Art in America and other magazines. He is the co-author of Tales and Traditions: Storytelling in Twentieth-Century American Craft.

Documents Northwest The PONCHO Series

Sis Jewelers: Flora Book, Ken Corey, Robert Davidson, Mary Lee Hu, Kiff Slemmons, Ramona Solberg

Seattle Art Museum

Seattle, Washington

April 22 - June 27, 1993

by Dana Standish

This is the museum blockbuster metals exhibition that metalsmiths dream about, or ought to. Here we are, finally, six jewelers in a real museum, with all the other real art, and no mention whatsoever that metals may or may not be an art or a craft or equal to or different from real high art. This is the show that we've all been bellyaching about.

It would be difficult to imagine a show of work more diverse than the work of these six jewelers. According to Vicki Halper, a former ceramist and now Assistant Curator of Modern Art at the Seattle Art Museum the artists were chosen with diversity in mind. Her intention was to find jewelers with "strong, different personalities," so that she could show "the varieties of expression in jewelry, just as there's variety in painting and sculpture."

Flora Book strings silver beads and lengths of tubing onto strands of monofilament to make her fluid "liquid silver" bodyscapes. The monofilament becomes nearly invisible on the wearer, so her pieces become sort of a living form that moves with the wearer forming a very intimate and personal relationship. These pieces are concerned almost totally with form and not at all with meaning, though they are not without their own kind of whimsy. One example, Double Ruff Neckpiece a sort of clown's collar that seems to have a life of its own could be poking gentle fun at our pre-occupation with fashion.

Robert Davidson, From British Columbia, works within the traditions of the Haida culture. Though he has an international reputation as an artist, this is the first time, according to Halper, that he has been in a show that was not devoted to indigenous art. His work shows the rich tradition of Northwest Coast art: his themes are the shapes of nature and animals, and man's relationship to the natural world. His pieces diverge from strict tradition in their notable absence of symmetry. His simple motifs have a grace and power that comes from the tension between positive and negative space, and from Davidson's re-evaluation and personalization of a traditional aesthetic.

The featured works of Mary Lee Hu are a sort of mini-retrospective, spanning the years from 1969 to 1993, which gives the viewer the opportunity to see the changes in her work over time. Her earlier objects are quite mysterious, more organic in form than the recent work. The early pieces appear to have been made in an intoxication with the properties of wire that must have seemed virtually limitless. Wire is made to do just about anything that anyone could have imagined, and then some: it is woven, twined, wrapped, and twisted into shapes that are simultaneously completely organic and utterly controlled. The recent work is also more meticulous in construction and more rigorous in design, with graduated interlocking woven shapes of microscopic twined gold wire. All these separately-woven shapes are joined together so perfectly that I think Hu deserves an award for the best non-soldering solderer in the field.

Ramona Solberg is one of the guiding lights in the contemporary jewelry movement. She has single-handedly spurred legions of found-object lovers to near frenzy with her witty and peculiar works. The pieces are totally unconcerned with "meaning" and instead show the irrepressible spirit of a true iconoclast. Her design sense seems completely natural and unstudied, and her materials seem chosen simply because they belong where she puts them. The artist's recurring materials are die, game pieces, and buttons. She uses simple materials and techniques, which allow the hand and the eye of the maker to display the power inherent in even the simplest objects.

It has lately become a cliché to rave about the works of Kiff Slemmons, and as much as I hate to be on the bandwagon, I am sorry to report that I must join in the raving. The irresistible appeal of her images resides in the fact that she is obviously using her work to search for meaning, and she uses the most simple, obvious materials that make the viewer ask: "Now why didn't I think of that ?". The power of her pieces lies in their directness, and in the many different levels to which they appeal. Protection is a play on a Plains Indian hairpipe breastplate, this one made from sharpened pencils lined up on top of each other. The pencil brand names: "Supreme", "Empire", "Executive", "American', are powerfully evocative of our long and tangled relationship with Native Americans. Some of Slemmons's pieces run the risk of slipping into cuteness with their use of puns. The images are interesting by themselves, without their titles, which often undermine their visual power. Figure Out, for instance, has a human "figure" with the word "out" floating inside its ribcage. The word serves no purpose other than to make a cute title. Touches such as these serve to diminish the seriousness of the whole body of the artist's work.

Ken Corey is regarded by some as being in the pantheon of modern jewelry masters, but I have to admit that the appeal of his works is lost on me. I can appreciate his pieces as part of a small, quirky world, but it is a world to which I have no access. His works are small, sculptural pieces that are to my eye a bit too ambiguous. I want them to mean something and they simply refuse. They all look too small for their own good, as though they are waiting to break free. He was considered in the '60s to be subversive and idiosyncratic, and I have no doubt that were I a better person I would see the appeal of his work.

Curator Halper says she put this show together because there was "a huge vacuum in the field" as far as the showing of "crafts" in a museum was concerned. She says she tried very hard to get other museums to take the show after its run in Seattle, as it is the size and scope of other traveling exhibitions, but no other museums were interested. This exhibition has received very positive feedback from the public and from the museum. Let's hope it serves as inspiration for other museums.

Dana Standish is a metalsmith and writer from Seattle, Washington.

Robert Ebendorf

Rings and Things

Farrell Collection, Washington D.C.

March 28 - April 25, 1993

by Dorothy Spencer

For the past twenty-five years Robert Ebendorf has been reemploying existing materials by devising ingenious uses for what has heretofore been discarded, discovering ways to make new materials from the used. Known for jewelry that includes everything and anything that he has found, he continues his on-going investigations into "REpresentations".

Ebendorf's conceptual approach to jewelry-making, which questions the nature of adornment itself, explores alternative concepts and materials. The creativity of his jewelry lies not simply in the intellectual repositioning of familiar objects, but in more physical transformations of material, that, in the end, astonish the viewer. And it is exactly this sense of astonishment that gives his pieces their value. It is the profound incongruity between what they are made from, and what they are now that so engages the imagination.

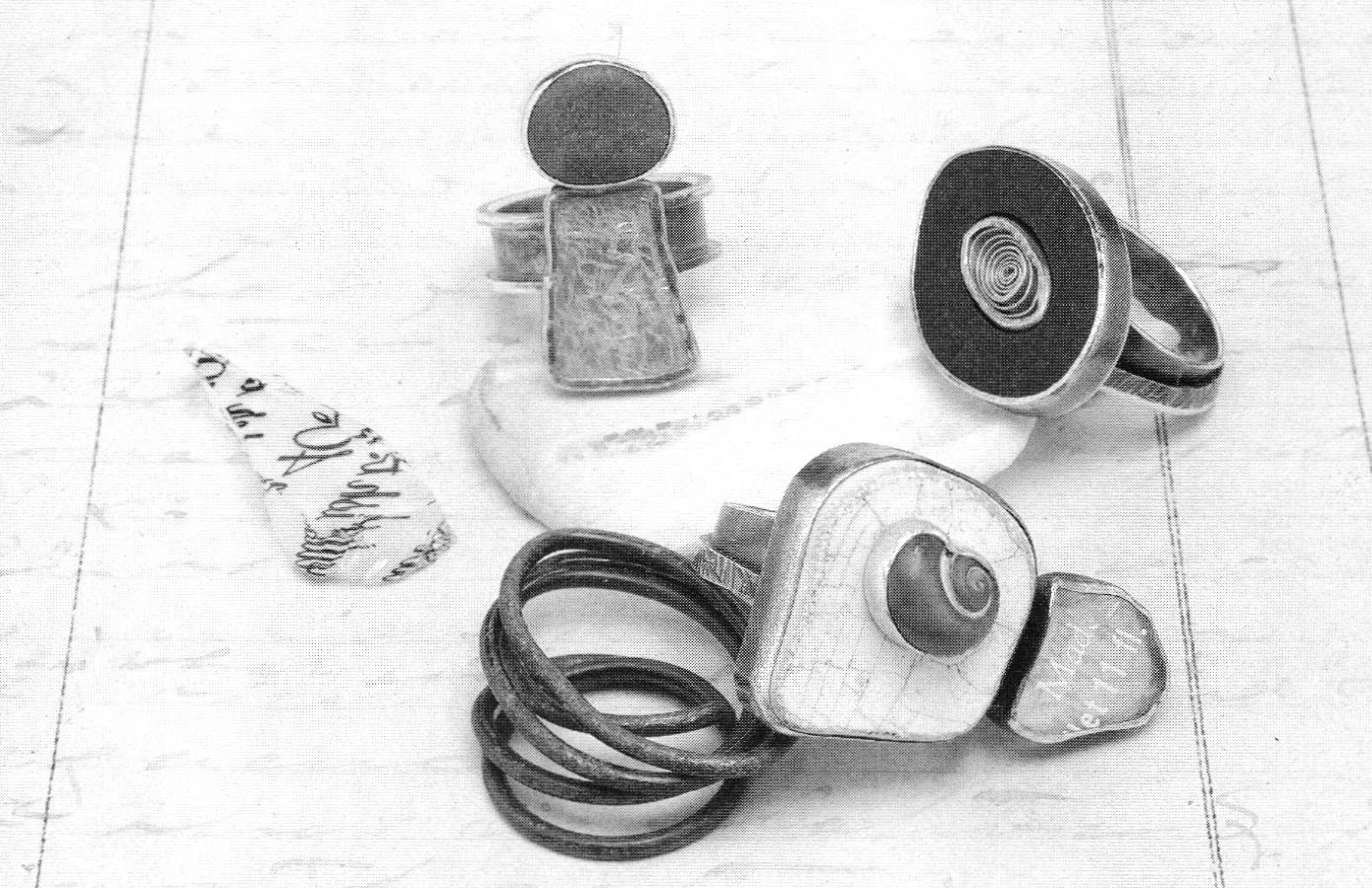

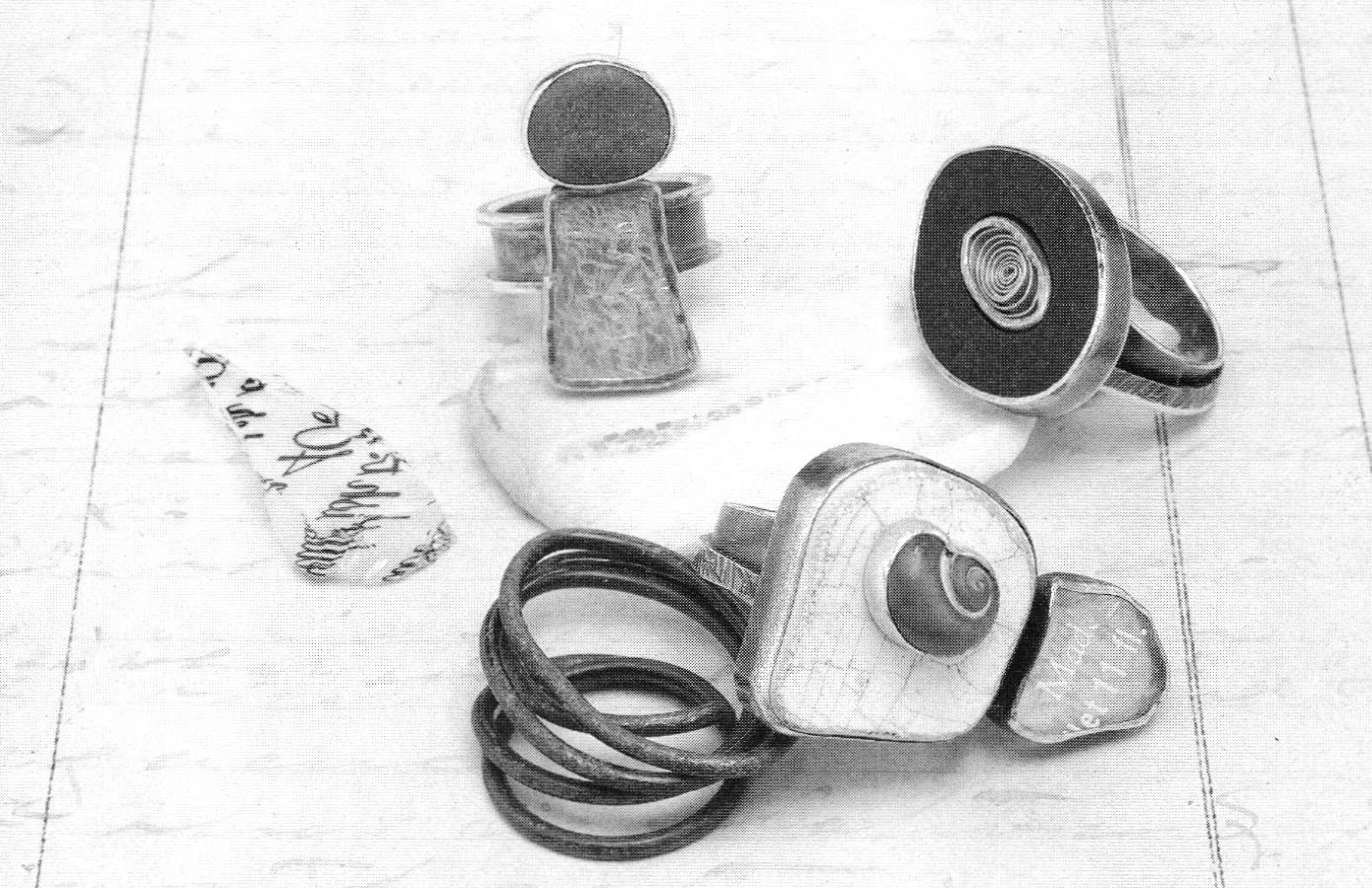

Ebendorf's latest exhibition at the Farrell Collection in Washington, D.C. in April provided a look at his most recent use of the discarded and the found, while continuing to question the old established definition of jewelry. Many of his newest pieces are necklaces and rings made from silver and/or gold which encased, not the usually expected gems, but shards of pottery, colored glass, sea glass, shells, and other assorted materials one would find combing the beach or walking in the woods.

Meticulously crafted, many reflect a turn toward the more naturally found object - a beautiful stone, a piece of a shell - juxtaposed with a shard of glass, fragments of writing still legible - a combining of the physical world with pieces reflecting those of civilization. In many there is a suggestion of the beauty of native American designs reinterpreted using the discards from Western civilization.

Other pieces, such as the large rings, containing round, flat surfaces, with the colors of the found objects muted to compliment as well as reflect the metals that hold them, are reminiscent of 17th century signet rings.

Robert Ebendorf's objects are not simply about refashioning the mundane. They reaffirm the value of that which otherwise might be without value. By reassessing the meaning of artifacts of daily life, they often reverse the idea of what is precious. If it is the purpose of artistic expression to locate and reaffirm values in our world, then this work is all the more relevant as a mode of contemporary expression.

Dorothy Spencer is a writer who lives in Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Gorham Masterpieces in Metal Exhibition

5 German Jewelers Marketing Strategies

Enamel Arts From Korea and Japan Exhibition

GZ Art+Design Spots 2007 4

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.