Metalsmith ’93 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

29 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1993 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features John Iversen, Pamela Ritchie, Carrie Adell, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

16th Annual Philadelphia Craft Show

Philadelphia Civic Center

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

November 4 - 8, 1992

by Dorothy Spencer

Offering everything from the innovative to fresh interpretations of the obvious, from the conventional to the Fantastical, the 16th Annual Philadelphia Craft Show opened November 4, 1992 to a record-setting attendance and, according to a poll taken among exhibitors, record-producing sales in what had been noted as a lackluster year for the art market as a whole.

The show, recognized as one of the most prestigious juried craft shows in the United States, set another record this year, having received submissions from over 1,650 artisans. And from that exceptionally large number, the work of only 175 were selected to exhibit. Of those exhibiting their work, 52 were categorized as either jewelers or metalsmiths, and these artists filled nearly one-third of the show's booths. This may be why seven of the fourteen prizes awarded went to metalsmiths.

The show's first prize went to Gael and Howard Silberblatt of Lake Worth, Florida, for their highly original cloisonné jewelry. Their collaboration created one-of-a-kind pieces using 18k gold settings with 24k gold cloisonné images. Many of the pieces were reversible, showing images on both sides of pendants and bracelets. Miniature in scale, with most under an inch in height, the designs were reminiscent of Renaissance triptychs and Medieval altar pieces, although the subject matter was very contemporary. Montages of cats, dancing dogs, bathing beauties, and skyscrapers juxtaposed among colorful, mosaic-like backgrounds, were elegantly framed in gold. All of the individual pieces were superbly crafted and they reflected the artisans' mastery of their techniques.

Lilly Fitzgerald of Spencer, Massachusetts won the Franklin Mint Prize for Excellence in Jewelry Design. Her brooches and pendants were beautifully executed examples of goldsmithing. Her work is very simple in design; most of her brooches of 22k and 24k gold are circles. Their settings of pearls, seed pearls, diamonds, and other gemstones such as lapis lazuli provide the dominant focus. The colors set the mood.

Another top prize winner was Randy Stromsoe of Cambria, California. Stromsoe, who won the Rolex Prize for Excellence in Metal, was the last master craftsman to apprentice with Porter Blanchard. He exhibited a group of well-crafted bowls and pitchers. One series of darkly patinaed pitchers, ranging in size from 7 x 4½" to 12 x 7½" were unusually designed, their wedge-like shapes much more sculptural than the usual postmodern combinations of hard-edged and semicircular and circular lines. In his creamers, he carried this geometric wedging to a greater extreme, reducing the design to just three shapes: circle, triangle, and arc, creating a set of individualized pieces. Stromsoe's command of the media, (he works in both sterling silver and patinaed pewter) coupled with his own personal interpretations, made an impressive exhibit.

Works ran the gamut from cast jewelry to very individualized, one-of-a-kind pieces, Among the more popular examples, the "techno-romantic" work of jewelry designer Thomas Mann, as usual, provided a fresh approach to cast jewelry with expertly constructed necklaces, pins, and earrings that were miniature collages created from industrial materials coupled with photographic images.

At the other end of the spectrum the serenely elegant, one-of-a-kind, silver teapots of Michael and Maureen Banner evoked the curvilinear lines of German Art Nouveau. The subtle curves of these objects, their sweeping, fluid lines, and the pristinely designed, cloisonné lids that completed each piece, were superbly fabricated.

Other exceptional objects were the works of Ken Carlson. At a distance his pieces reminded one of the teal green, rush-woven, Native American vessels indigenous to the marshland regions of South Carolina. Only on closer inspection did one realize these richly patinaed baskets had been meticulously woven from copper strips. The artist's command of the material along with a mastery of the intricacies of weaving techniques was obvious in the simple, yet sophisticated designs which made the pieces unique.

Eric Olson's fabricated pewter vases, bottles, teapots, and goblets, were highly stylized and many were exaggeratedly geometric in shape. Skillfully-crafted, they provided a fresh insight into the use of a centuries-old medium.

The show, which seems to grow larger in size and better in quality each year, represented a very high level of quality and craftsmanship spread over a significantly broad-based area of design arts. One highly individualized interpretation of jewelry design could be seen in the work of Pat Flynn. Elegant and meticulously-crafted, his pieces juxtaposed common found objects, such as rusted nails, shards of discarded slate, and pieces of barbed wire with diamonds, gold, and other precious and semi-precious metals and stones. These unlikely unions created profoundly unusual vet exceptionally beautiful objects - Flynn quite literally rearranged the ordinary into the extraordinary.

The sculptural work of Didi Suydam provided another aspect of the show's diversity. Her sterling silver and gold pieces were both objects and pendants. Each piece came apart to reveal a chain contained within. These elegant, reductivist pieces were unencumbered by jewelry findings - pure, abstracted forms, that could also be worn.

Equally unique were the hinged and sculptural containers by Ron Hinton. Created from bronze, copper, brass, nickel silver, as well as various combinations of metals, these boxes incorporated the traditional function of boxes with angular forms and planes that projected into space. Even the hinged lids seemed less a part of the function and more a necessary and sometimes surprising part of the form. Images of landscapes, including aerial and satellite photographs, computer-generated contour maps, and graphic patterns were photo-etched onto many of the planar surfaces. These beautifully crafted objects were as functional as they were stand-alone, abstract sculptures.

With so wide and diverse a group of exhibitors it was impressive to see such a high level of quality. The artists revealed an impressive depth of knowledge of the extraordinary variety of mediums used, and their capabilities were reflected in the many innovative methods of handling and manipulating the materials. It is rare when such a broad spectrum of interpretative styles and vocabularies representing the many provocative directions within this field are found in one exhibition. The Philadelphia Crafts Show provided such a vehicle.

Dorothy Spencer is a writer living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

John Iversen

Art Wear

New York, New York

October 15 - November 12, 1992

by Lanie Lee

The crux of John Iversen's exhibition was formed around the inner workings of nature. Iversen's work captures the subtle, structural variations and color transitions of geology and biology in such a way that the perception of the parallel between the artist's own evolution and that the evolution of nature is unavoidable. Works created in the early eighties up to the present may have denoted different styles and materials (from the copper and enamel used to make solid rock-like forms to the delicate, linear leaf shapes made from oxidized bronze and nickel silver) but they never strayed too far from their models in the natural world.

In both the jewelry and the functional objects (candle holders and bowls), one could see many of the basic patterns found in nature. Bronze Cuff, a wrist piece of oxidized bronze (1986), has thin strips that curve into a sphere; spaces in between the strips enable viewers to see the entire form. The apparent randomness of each curve, and what seems almost like imperfections, lends both simplicity and elegance to the design. Iversen also employed similar methods to make objects such as bowls and candle holders: Bronze Bowl (1991) and Candle House (1992), both made from oxidized bronze. Though the lines of the shapes are more uniform in the utilitarian pieces (organic lines and curves in the bowl and sharp-edged, more architectural, geometric shapes in the candle holder), than in the bronze cuff, they all share an almost primitive quality that is accentuated by their exposed armatures. One can see through and around all of these pieces. Thus the infrastructure is exposed and lays bare the design.

It was intriguing to trace the evolution of Iversen's work. During the 1980s, Iversen made bulky necklaces and bracelets in the shape of weighty rock forms. Pebble Pendanx, (1982), copper, enamel, and antique metal threads, had the dimensions and textures of real pebbles and gave the illusion of heaviness. Apart from the metal threads surrounding each stone, the pieces blended in so well with the real stones used in the display that it was hard to separate the two. Keeping his contacts with nature as a source into the nineties, lversen exhibited grain shaped beads, linked into delicate Grain Necklaces. Using cast and oxidized sterling silver for his beads, Iversen made strands of sterling silver grains combined with red coral, pearls, and vermeil. These natural objects offered an interesting contrast between geological and biological forms. Iversen's highly skilled hand, in the manipulation of materials to re-create both the macro and microcosmic elements in nature, was more than evident.

One could say that Iversen has a true-to-life attitude towards nature. His work maintains the timeless characteristics of nature as well as exhibiting its fragile vulnerabilities. Leaf Pins, of oxidized bronze and nickel silver, (1991), depict intricate life-like leaves at various points of erosion and decay. Viewing these different stages of metamorphosis, one senses the frailty of nature - as if they could transform these replicas of dried leaves into dust by clenching them into the palm of their hand.

The success of this exhibition was also assured by the manner in which it was presented. There were nine cases that held each type of work. Pieces of driftwood were used as pedestals for leaf pins; rocks were used in displaying pebble pendants; and necklaces were hung from plaster body fragments. From case to case, sensitive and thoughtful presentation helped viewers' focus on the continual flow of lversen's ideas.

Lanie Lee is a writer and editor residing in New York City.

Pamela Ritchie: Concatenation

Galerie Jocelyne Gobeil

Montréal, Québec, Canada

October 14 - November 21, 1992

by Jean-Claude Leblond

Canadian artist Pamela Ritchie's perspective on her work is as equally concerned with jewelry as with sculpture. "I do not consider myself a sculptor but rather more as a Jeweler even though this term is not very precise and tends to refer more to work produced in series. I would have to say that I am an artist creating jewelry." Head of the Jewelry Department at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Ritchie considers her work to have two statuses. "When they are not worn they appear as miniature sculpture. Contrarily, when placed upon the body they become jewelry. I firmly believe in the body's function of wearing this work and it is within this context that it takes on its full meaning and value."

Through their organic forms, her work refers to religious symbols and symbols of food such as the fish, a dominant theme in Christian cultures. Equally, however, her work subtly touches upon certain archetypes of the human psyche. "Because it is jewelry, my work has a strong relationship with the body, but because of the intimate nature of jewelry this work has an even stronger relationship with the mind."

In her recent exhibition at Galerie Jocelyne Gobeil, Ritchie presented the results of her investigations over the past years. These strong works, delicately constructed in gold, silver, copper, and brass, are subtle expressions filled with internal meaning and discretion. We do not find in this work any desire to self proclaim. Her pieces are inhabited by the image of her personality and through them she conveys the contemporary need to re-connect with that dimension of existence that goes beyond our logical and rational comprehension. Her choice of warm metals appearing to have an almost porous quality offers lively materials that also communicate within this sense. It is a sense not foreign to a form of piety. "These are works in relief from the body, that express the body and surpass the simple function of ornamentation", affirms Jocelyne Gobeil, whose gallery, one of the few in North America to specialize solely in contemporary art jewelry, presents the works of jewelry artists from all over the world.

One could almost say that, because of her attachment to great symbols and to the inherent contradictions of existence, Ritchie's jewelry is preoccupied with the metaphysical. As she says: "They represent a modus vivendi for dealing with the opposites of nourishment and deterioration, tolerance and fanaticism." Here, we are going beyond the simple decoration of clothing and entering directly into the realm of art, with its desire to pronounce its beliefs about the world, to participate in its beauty and also the dangers that threaten it. As well, at the heart of these magnificent organic forms, we detect a tear that longs to appear, a rear of sadness or joy, a tear that reconciles the contradictions. And as Charles Dickens wrote: "Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth."

Jean-Claude Leblond is a writer and critic who lives in Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Neoteric Jewelry

Snug Harbor Cultural Center

Staten Island, New York

September 21, 1992 - January 19, 1993

by Jan Baum

Neoteric Jewelry, curated by Louis Mueller and organized by the Snug Harbor Cultural Center opened on September 21, 1991 at the latter's Staten Island location and remained there until January 19, 1992. The exhibition traveled to the Society of Contemporary Crafts in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (May 8, 1992 - August 16, 1992) and reached its final destination at the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design (September 10, 1992 - November 15, 1992).

The Neoteric Jewelry or "new jewelry" exhibition included the work of twenty-five international and national jewelers. Each participant was asked to create one new piece based on the theme of "virgin". Mueller's theme was defined as "something unexplored, fresh, concise and absolute". By assigning a subject, the curator's intent was to make the artists' definition of the object more clear; and to challenge the artists to "think outside of an accustomed way of thinking." Although the parameters were imposed, it was clearly not difficult to think "outside" of those parameters when dealing with such potent, socially and historically charged subject matter.

As one would expect, much of the work exhibited fell within the realm of accustomed responses. These ranged from literal interpretations suggesting moral connotations: Robin Quigley's The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, Sandra Sherman's Delilah I. Sketch, and Warwick Freeman's Soft Star; to sexually connotative works: such as those found in Detlef Thomas' Cockring Giampaolo Babetto's Virgin #1, with its ruby crotch, and Joyce Scott's more palatable, Laying in Wait; and finally to the more formal responses of Therese Hilbert, Daniel Kruger, Annette Ferdinandsen, and Johan van Aswegen. It was where the gaps between the poles of these customary responses were filled that one found the real meat of a show. When the gaps remained unfilled, comprehension was hindered, often times leaving viewers feeling disconnected.

Manfred Nisslmuller's scrupulousness was evident in Virgin-Ring, which was presented in a box lined with a stately red fabric. The artist coupled this elegant fabric with common marbles which suggested childhood. A small gold ring, which overlapped instead of forming a continuous band, floated in the center, untouchable and apparently waiting for the right owner, or the exact moment to be given away. This combination of elements hinted at the artist's interpretation of the theme (innocence and fragility), as well as echoing the text found in the catalog. The text reads, "A child will wear the ring. The glass will break, the balls will be lost, the red will lade away, the gold will disappear and the ends will meet. A woman will wear the ring."

Among the more intriguing entries were works by Leslie Quint and Falko Marx. In Quint's neckpiece two shapes, a dark, solid knife-like form and a delicate, sterling, feather-like shell, dangle from steel cables;. Both are attached to a third, slightly thicker, steel cable meant to be worn around the neck and on which the other forms rotate. The metaphorical qualities of natural shapes, suggested by Quint, address a harmony of forms. While independent these two objects complement one another.

Merkur, a brooch by Falko Marx, entices viewers with liquid mercury captured within a gold container. Marx's choice of material is a provocative one. The sensuality and the stillness of the mercury tease the viewer. It seemed appropriate, in the context of the exhibition, that the viewer was denied access to the brooch and therefore could not further disturb and explore the work. Yet, even if worn, the mercury in the golden vial will always remain protected and unadulterated.

The works of some artists in the exhibition make allusions to nature. Barbara Seidenath's enameled earrings resemble pods. This impression is reinforced by the small coral "seeds" that poke out from the bottom when the pieces are handled. The white enameled exterior provides a housing for the orange coral seeds that reside in the interior and the organic nature of this form is suggestive of the feminine. Bernhard Schobinger's quartz ring presents the "unspoiled purity" that is often found in nature. The circular break which allows the quartz to be worn is "a perfect work of Nature", while the precise planes of the outer part of the ring have been created by the artist.

A major drawback to this exhibition was the lack of clarity and connection between the pieces as a whole and the absence of certain works' clear relation to the theme. If a viewer had entered one of the three exhibition spaces without reading the introductory playcard, the exhibition may well have appeared to be merely a show of contemporary jewelry. Even the informed viewer had rigorous work to do. The works which appeared to be largely formal or abstract left the viewer to speculate about the connection of the pieces to the theme. Was the artist working in a manner which was unfamiliar to them? Was the artist responding to an idea that they had not previously considered?

Although a breach between objects and theme often occurred, the accompanying catalog was, and still remains, a very helpful guide to deciphering the show. It clarifies Mueller's intentions and, in many cases, supplies texts which augment individual pieces. Mueller's purposes and contributions went beyond the theme already addressed. He also intended the exhibition to introduce international jewelers' works to American viewers (a credible maneuver which may enrich our sometimes "national" palate.)

This was the first show that Mueller curated so he too, somewhat ironically, was a part of his theme. In addition to the two rooms which housed the exhibition at the Museum of Art at RISD, a third room displayed a number of the curator's own works from the late 1960s, 1988, and 1991. It was unclear, however, what connection, if any, this group of work had to Neoteric Jewelry other than exemplifying the curator's personal work.

It is apparent that some of the confusion viewers may have experienced was the result of Mueller's multiple intentions. While I endorse this method of structuring an exhibition, some questions still remain. Was the exhibition primarily meant to be about the theme? Was the intention in assigning a theme to gain a deeper understanding of the subject? Finally does the viewer come away from Neoteric Jewelry with new perceptions regarding the term "virgin"?

Jan Baum is a metalsmith who lives in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Earthspeak: Carrie Adell

Running Ridge Gallery

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Winter 1992

by Ellen Berkovitch

Carrie Adell's pronounced interest in letting the earth speak is the leitmotif of her recent work, and this approach provides a clear voice for unifying materials and designs. The jeweler calls the work "right brain" jewelry, and this new work serves as a contrast to her previous "hyperbolic parabola" series of clean, three-dimensional metal links with interlocked vectors, in which movement flowed naturally from geometry and which represented an intellectual challenge, overcome. The work recently displayed appeared on first glance to break little new ground, but on closer inspection these newer works revealed powerful tactile and visual strengths: the feel of the polished pebble shapes in the wearer's hand and on the wearer's body; the cohesion of the pattern in the gemstones with the pattern the jeweler creates in the matched metal; and the burnished and sedimentary colors that capture as closely as possible their original rock strata influences.

This is jewelry whose strength comes from its emotional impact over time. It invites close, wearer interaction with both its forms and meanings. The jeweler even names the parts of the assembled pieces after the natural forms that inspired them - the metal sheet is the "fabric" of the rock; the oval shapes that repeat through the collection are "pebbles" which, at craft shows, she displays loose along with finished pieces. The process of picking up pebbles, Adell says, re-invokes an instinctual neural pathway that is childlike, therefore intuitive and natural. The collection itself coheres through the repetition of the pebble shape, and the group of works are reminiscent in their idiom of Helen Frankenthaler canvases which carried forward experiments with poured color across a subtle continuum.

Revealing the artist's interests in patina, broken laced pairs, and evoked emotional content, every piece in the collection begins with the "fabric" that is: a worked metal sheet that may mix sterling, gold, and nickel, or the fabric may be assembled entirely of scrap to create a particular coloration and design matrix. Adell then engraves the metal surface and mimics the natural imprints of the attendant gemstones, or the engraved markings may reflect the ceremonial writing of her own haiku, or sometimes merely an emotive state, such as the "seismic" black pebble brooches and bracelet clasps that were etched with gold shock-waves to dispel the artist's anxiety about aftershocks of the last San Francisco earthquake.

The gemstones Adell chooses have a natural luminosity and contrasting occlusions, and the artist displays evident preferences for boulder opal, schist, and other hard quartzes that "fight back". While the stones themselves create certain mandates for a finished piece, the metalsmith says she doesn't consider herself to be "an environmentalist for gemstones." Rather, her interest, as expressed through this recent collection, was to let the gemstones create an environment of earthly awareness and history that becomes the tie that binds disparate pieces together.

One is reminded of a 1950s science fiction movie in which "hypnoglyphs", (rock creatures) hypnotized, and then persuaded able-bodied men to enter an alien spaceship in order to enrich the gene pool of the alien culture. It is the power of the rocks themselves that is the deceptively simple focus of Adell's new work.

Ellen Berkovitch writes about jewelry and the arts from Santa Fe, NM.

Imperial Austria: Treasures of Art, Arms & Armor from the State of Styria

Smithsonian Institution, International Gallery

Washington, D.C.

October 3, 1992 - January 24, 1993

by J. Susan Isaacs

The most important collection of arms and armor in the Western world was on display at the International Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution through January 24, 1993, and continues at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, March 14 - June 27, 1993. The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue published by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Prestel-Verlag, Munich. For the first time outside of Europe, a major collection of armor from the Landeszeughaus in Graz, Styria, the oldest and largest historic armory in the world, is presented. Included in the exhibition are more than 250 works of late-Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque art, arms, and armor, which reveal a stunning technical and aesthetic achievement spanning a period of three centuries. Clearly, Austrian armament was not merely functional; the quality of design and craftsmanship paralleled the fine arts and even led to the creation of a new medium: intaglio printmaking. All of these works were produced for the fighting men of Styria, a borderland defense region controlled by the Habsburg.

Because of aggression from the Ottoman Turks in the fifteenth century, arms and armor became increasingly important to the defense of Styria, which had no natural geographic borders. Graz, the capital city of Styria, had three armories to store the vast collections of the resident armies and the reigning prince. Of these, the largest, Landeszeughaus, was primarily responsible for the fortification of the province of Styria, including cities and border strongholds. Its arsenal, amassed over three centuries, remains intact, and the 250 items in this exhibition were chosen as representative samples of the arms and armor used to assist in the protection of the Habsburg Empire from the time of the first Ottoman invasion in the fifteenth century up to the eventual defeat of the Ottoman army in 1683.

Previous to this era, mail (interlocking rings of metal) was the predominant form of body protection in battle; however, by the fifteenth century, because of the need for protection from a relatively new threat - firearms, armor had evolved From mail to plate. Unlike mail, plate is a natural medium for decoration and artistic expression. Until the industrial revolution, armor and arms were, for the most part, one-of-a-kind, uniquely crafted works of art, in addition to being highly useful objects in war and defense. Originally, heraldic devices were placed on the armor so that the identity of the concealed warrior would be known. Ultimately, these designs evolved into highly ornate and extremely decorative compositions.

One of the most striking pieces in the exhibition was made by the master armorer Michel Witz the Younger, around 1550. This ¾ suit of armor has an embossed black and white finish in a stylized leaf pattern. This pattern was created by darkening some areas and polishing others to a smooth gleam. The ¾ suit is an extraordinarily elegant work and epitomizes the beauty of the Landeszeughaus collection. Patterns were also applied, using a variety of techniques, to the surfaces of daggers, swords, lances, handguns, and rifles, as well as suits of armor. Of particular interest to metalsmiths is the wide variety of examples of etching, painting, oxidation, gilding, repoussé, and inlay, which are included in this exhibition. Surely, anyone interested in the history of metalcrafts and metallurgy will find this exhibition challenging, informative and fascinating.

J. Susan Isaacs is an art historian and critic from Wilmington, Delaware

Metamorphosis Convertible Jewelry

Atrium Gallery

New York, New York

December 18, 1992 - January 7, 1993

by Gail Brown

Helping to engage the wearer in making personal choices in the presentation of ornament may be a step towards enlarging the audience for contemporary art jewelry. METAMORPHOSIS/Convertible Jewelry, presented by Atrium Gallery, New York, addressed this concept of active choice by focusing on the dialogue between gallery owners and their clients. The 44 artists invited to participate were challenged to create jewelry which is wearable in multiple ways. Most of the resultant work was high carat gold and precious stone items, de rigueur for a Fifth Avenue clientele, and along with investment-size prices came traditional, sound workmanship and often non-challenging design. Yet for an audience looking for both quality and innovative solutions to convertibility the exhibition did not disappoint. The breadth of the show was commendable and there were a smaller group of artists who addressed the potential of convertible, sculptural jewelry in particularly unique ways. For some, this exploration is a natural consequence of their usual design and engineering pursuits. There was also a wealth of well crafted, classically referenced pieces which addressed predictable solutions to interactive jewelry: pendants which became brooches and vice versa; necklaces which became bracelets and shorter necklaces; brooches whose smaller elements are stick pins, etceteras.

Nancy Michel's 2″ dangle earrings of softly folded 14k and 18k gold sheet with delicately striated surfaces presented the wearer with four choices. Each element was individually significant in scale and concept: a ¾" closed form sits in the earlobe, a curled, 1″ leaf-like pendant can be attached, thus creating what appeared to be one compound element. Though both forms can be worn alone successfully, more adventurous wearers could opt for an asymmetric pairing. The strength of this work was the integration of the design with the sureness of each function. These pieces beckoned to be handled.

Alexandra Watkins exhibited a reversible 15″ necklace composed of 14 unique, lozenge shaped hollow forms. Connected by delicate rings, the forms ranged from rectilinear to ovoid, varying in size from ⅝" to ¼" in length and with a depth to ¼". There was a sense of an organic landscape in the richly textured repoussé surfaces. The oxidized sterling side with 22k accents presented an introspective territory of irregular patterning and strong contrasts. The 14k and 18k side brought the landscape into the light with rich and subtle variation.

On a 24″ oxidized silver, herringbone chain, Nina Ehmck hung a multi-pendant. Three sculptural, 18k and oxidized silver bleeding heart forms drooped delicately on narrow stalks, suspended from a curved yoke. Closer examination revealed the center 2″ pod to be an independent form, which hung from a straight shaft and could be worn singly. The two side buds were 1¼" earrings whose stems were connected to the yoke by their small diamond studs. The gentle movement of the components and the contrast of the materials and textures echoed the fragile essence of this flower; both the concept and execution reflected a successful parity of ideas and elements.

Cary Stefáni created a mixed pair of convertible rings in which horseshoe-like shanks and arched upper sections could be interchanged. The components available separately, were 14k white and 18k yellow gold shanks. They could be slid up and locked into place between the top sections: a crystallized bronze concave disc resting on 18k bars and/or a round pink tourmaline encased in a wide yellow gold bezel, sitting on white gold bars. There was real intimacy at work in these pieces: the wearer builds the delicate rings and chooses to display them singly or in stacks. This concept offers variety and unpredictability in addition to the fineness of the elements.

Rena Koopman offered recognizable elements from her visual vocabulary. With excellent problem solving skills she carried the assignment to a most effective resolution. In Metamorphosis #1, she presented what at first seemed to be a 2½" square brooch of 18k and 22k, gold with contrasting, inlaid shakudo. Four wavy squares clustered toward the center, were accented by rhythmically placed rods. However, this piece was, in fact, two rectangular brooches, each 1¼" x 2½" . But, it could also be four earrings, each 1 x 1″. Upon examination of the reverse side, one could find the delicate workings which held the two snap-out earring elements in place, within each rectangle. The well engineered design is an aesthetic winner: form and function mutually supportive with economy. In Metamorphosis #2, interchangeability was anticipated: an 18″ herringbone neck chain has as its center a ½" shakudo bead, accented by a diamond housed in a square bezel which is, in fact, the clasp. When unscrewed, one or two of the convertible elements can be added: a ⅞" square or a 1″ diameter disc of 18k and 22k yellow and 18k green gold. The surfaces, divided by raised rods and arranged asymmetrically, led the eye to the boxed diamond and shakudo accents. These components had a dual nature: they were also a pair of "button" earrings, whose post backs pivot on a small swivel. Koopman integrated her interest in how things fit together, physically and conceptually, with the utmost concern for wearability.

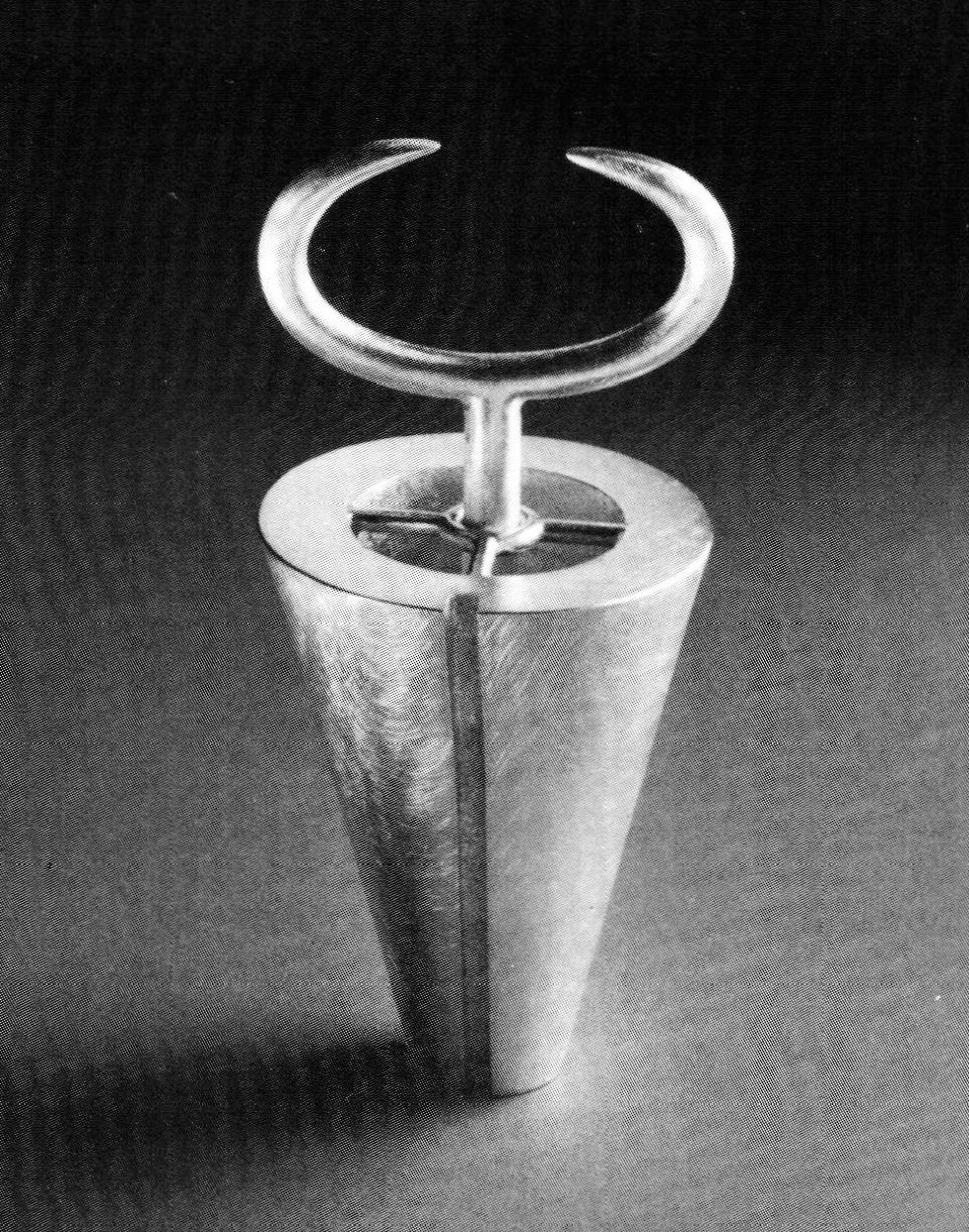

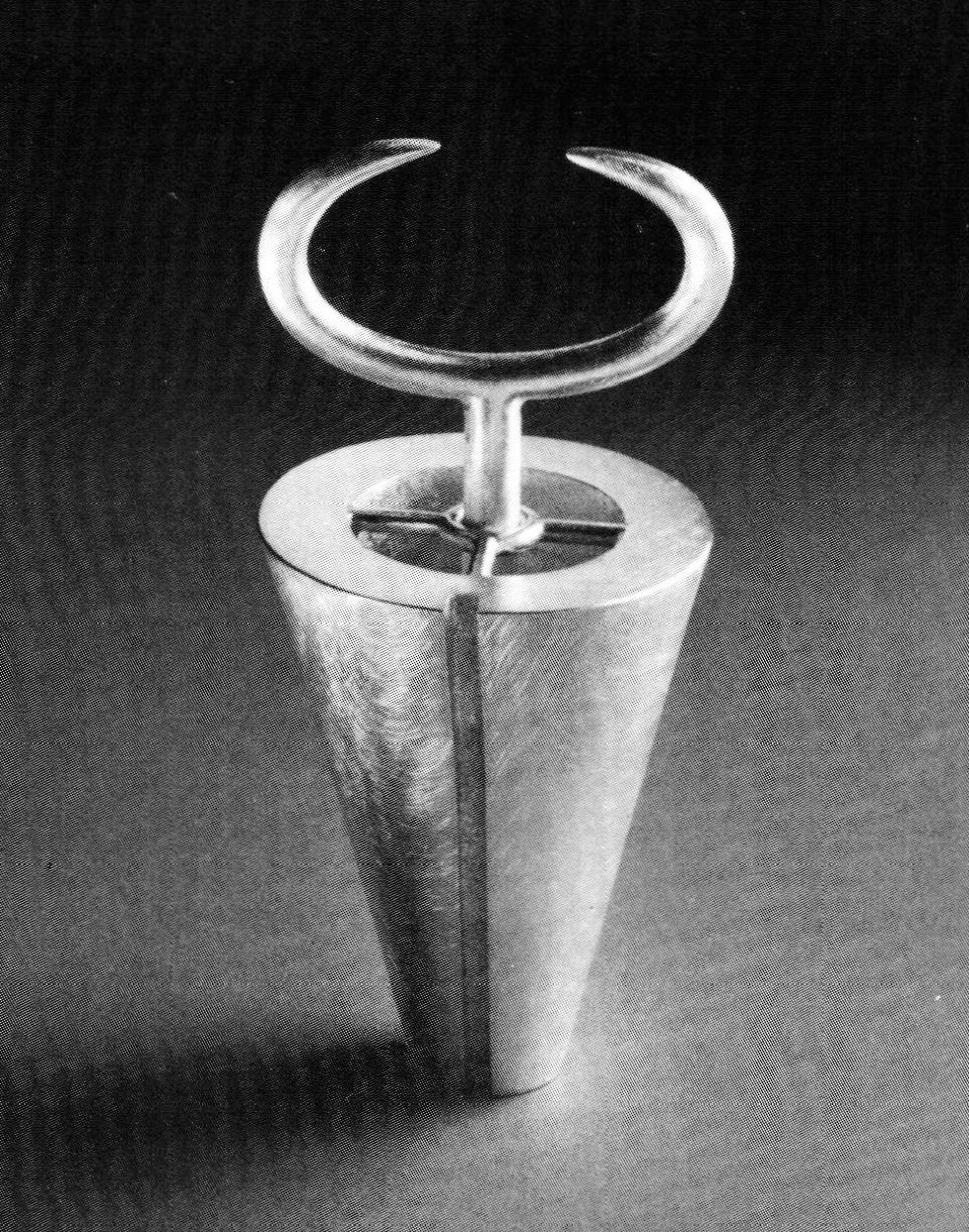

Didi Suydam addressed the challenge of convertibility in another direction. She has traditionally shown an interest in pendants as objects, concentrating on form unencumbered by jewelry fittings. These forms are intended to stand alone, to be powerful symbols when not on the body. They only reveal their wearability upon close and careful examination. Pendant, 1992, a 3½ x 1¼ x 1¼" brushed sterling silver and 23k gold leaf cylinder is topped by an upturned handle. When pulled a long, delicate loop-into-loop chain appears, revealing the connection of the vessel form to the head hole and then to a horn like extremity. The piece is meant to be worn front to back, accenting the body with both a fragile line and two medallion forms. Suydam integrates the power of the object with the personal ritual of wearing jewelry.

Poised on a hollow, burnished brass stand, a wing like rolled silver form by Yoshiko Yamamoto appeared precarious and rather like a double windsock, almost joining at the wide ends. Each burnished cone is 3″ in length, and the total work at 8¾" made a vital image. When the object is removed from its stand a large pendant which can be threaded through a 24″ thin steel cable is revealed. It can either be strung through the undulating wire between the cones, or threaded through the tube like ends; its dramatic gesture varying and dependent on which mood and placement the wearer chooses. Yamamoto also enticed one to choose with an oxidized bracelet of copper sheet, designed, cut, and formed. It is a series of triangles made from a large triangle whose center is a 3⅜" triangular armhole. From one direction its "arms" curl away, flowing and tubular. On the reverse, the focus is on the hole accented by 1¼" walls which frame the arm and emphasize the forward curled leaves. Even with an object of such simplicity the wearer is still offered the chance to make a selection.

In such a large exhibition there are many innovative pieces. When a majority of audiences still desire affirmation of their conservative jewelry decisions, a broad presentation, such as this one, serves as an educational tool. By inviting the viewer/wearer to examine closely, to handle, to manipulate the objects, and to make aesthetic choices, (even small ones) it is hoped that a new level of positive response to change and the "unexpected" can be achieved. METAMORPHOSIS was a truly challenging show and it invited creativity on many levels.

Gail Brown lives in Philadelphia and writes on jewelry and fine crafts.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Project Silver Summer Gallery

Metalsmith ’87 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

Pioneers in Enamel

GZ Art+Design Spots 2008 2

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.