Metalsmith ’93 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

23 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1993 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Thomas Mann, Stuart Buehler, Peter Chang, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Points of Departure: Four Masters Candidates and Faculty in Metals

University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth 101 Arch Street

January 23 - February 28, 1993

The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Massachusetts 175 Newbury Street

January 25 - February 26, 1993

by Gail M. Brown

The first in a series of exhibitions at The Society of Arts and Crafts to honor 1993, the Year of American Craft, the exhibition Points of Departure: Four Master Candidates and Faculty in Metals, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth was a testimonial to the value of the academic process at its best; artists who teach and creatively nurture the next generation's talent, while continuing to actively pursue their own work. A studio environment geared to promote individual exploration and interaction of technical and conceptual challenges and offering subtle guidance and ongoing dialogue encourages personal questioning and fosters risk taking. The visual evidence of this successful support was seen in the strength and diversity of the work presented.

Joy Raskin explores flatware as sculpture and social commentary. Almost every piece is functional, but, many ask us to reconsider that function as well. Her humor points to what we know of and what we do with objects. She offers original solutions combining functions of measurement, containment and manipulation of implements. She invents droll objects which address weight, scale, and flexibility. She asks us to think about the ideas of the function, purpose, and usability. Thermometer Spoon, 1992, (sterling silver, glass thermometer) gives us a visual wedding of cause and effect, and perhaps makes "the idea" of medicine easier to take. Her irony knows no bounds, and apparently her inventiveness is similarly unlimited. Hers is a youthful exuberance for materials, techniques and ideas and her fresh approach speaks of undaunted possibilities.

Currently working in mixed media, Linda Sherer imparts narratives of personal importance to functional furniture. The cabinets exhibited are about specific storage; familiar forms which address the nature of their potential contents. Speaking as much about the idea of a cupboard and a linen cabinet as to form, Cup Cabinet, 1992 (poplar, pecan veneer, slate, beeswax, dye, milk paint), celebrates a display case as a formal altar. The juxtaposition between the images - the wax cup and the potential for real cups to fill the four shelves - sustain the notion of how objects embody ideas. The work provokes thoughts about the relationships of furniture to sculpture, content to function. These possibilities are entertained while materials are explored, and historical references to furniture are made in new ways. She combines something unexpected with the familiar, making it quite individual.

Deborah Darr's works ask viewers to look at everyday objects and reconsider their potential. She deals with language, education and childhood games. She encourages exploration of our assumptions about common functional articles. She confronts viewers with ideas, invites participation and challenges them to reconsider. She focuses on the arrested moment, introduces phrases and unexpected contexts to every-day things. Imposing text and symbols onto found furniture she translates the pieces into non-functional sculpture whose images and ideas are provocative. Labor for Love, 1992 (wood, paint, chalk), appears to make play of memories of primary school, including smeared chalk boards and the ubiquitous apple for the teacher. The message questions that which seems all too familiar.

Amy Hudon's kinetic brooches are highly architectural and crafted to be worn in different ways. When worn they appear to be about structure and complex support systems; when closed they address more formal issues regarding linear and planar forms in asymmetrical compositions. Brooch/Structure II, 1992 sterling silver, 24k yellow gold, 14k green gold, and apatite, in the open mode stands away from the body and becomes a model diagram of engineering in miniature. The works of precious metals and stones, are elaborate devices referencing beams, struts, trusses and joinery compacted in a wearable scale. They are equally strong as design forms in open or closed, horizontal or vertical orientations. Within this body of work one appreciates the building of a dynamic vocabulary: an exploration of a range of mechanical possibilities, and a strong sense of accomplishment in their tabulation.

This exhibition also gives us the opportunity to see the most current explorations of the artists/faculty. Alan Burton Thompson has enhanced his new brooches with a more personal vocabulary by gold plating found object elements after they are joined. The resulting complex form has an integrated harmony, yet on close examination it still invites discovery of the individual, disparate elements. He continues to study the idea of the "medals" and the messages they carry from the specific to the anonymous. The works are normally 4 to 6″ in length, formal in attitude and vertical in gesture. He reorganizes the mundane into celebration and tribute which elicits stories of pivotal human events. In Sight Unseen, 1992 (24k gold plate on sterling silver and copper, acrylic, found objects), a combination of sentimental references creates a romantic pictorial whose formal tranquillity is disturbed by ominous possibilities. In several pieces he opens the space exploring line and drawing, delicacy and tenuous connections. There is a grace and lightness in these choices. The one or two elements left in their unplated state serve as emphasis through their difference, referencing the power which found objects have always had for the artist.

Susan Hamlet's evolving sensibilities lie in the continuing exploration of containers, but now, in jewelry scale. The graphic forms of the Basic Math and, Seasons brooch series have become vessels for storytelling as elegantly articulated bottles, buckets and jars. A select group of fabricated, miniature objects are housed within, becoming a lexicon of representational imagery: tiny tacks, draped cloths, tools and organic matter. Chosen limitations such as the use of constancy, duplication and only sterling silver to explore texture without color variation set the stages for the narratives. There is an evident exercise of intellectual power in the choices, the drawing and the forms, with messages that are ambiguous and have many-leveled associations. Elements of Escape, 1992 (sterling silver), presents an interior whose every object speaks of the possibilities of meaning, as well as the maker's pleasure in fabricating the individual forms. The relatively small scale calls for both exquisite articulation and a miniature monumentality. We know that nothing has been left to chance, particularly the uncertainty.

The diversity and depth of the exhibition prompted an unusually long examination which resulted in a great deal of information and satisfaction. With its historic imperative, the Society of Arts and Crafts, founded in 1897, continues to celebrate the interactive community of artists learning from one another and to educate and challenge its audience.

Gail M. Brown lives in Philadelphia and writes on jewelry and fine craft.

Thomas Mann: Food For Thought

Gallery I/O

New Orleans, Louisiana

January 9 - February 3, 1993

by Bettina Wulfing

Thomas Mann is finding time to philosophize about the world's condition. Mann, a jewelry designer since 1971, is nationally known for his innovative "Techno-Romantic" creations that combine found objects with metal materials. Food for Thought is the artist's first solo exhibition of sculpture, jewelry and furniture in New Orleans and it reflects the contradictory reality that we live in a world with plenty of food, yet, many individuals, locally as well as globally, are still starving.

Political, social and religious issues that prevent food from reaching the hungry are the topics addressed by the pieces. The wall sculptures that form the Hunger Series are prefaced by printed statements on hunger such as "American consumers save, on average, a nickel on every hamburger imported from Central America, but the cost to the environment is overwhelming and irreversible." Smaller amulets are showcased in Plexiglas and wood wallboxes. The Space Frame series is made up of sculptures and jewelry in the forms of metal grids which hang from the ceiling and are welded with objects that are both new and recycled. The shapes of these grids resemble missiles and bombs. These large three-dimensional sculptures frame photographs, bullets, barbed wire and grains. A group of metal neckpieces have engraved titles such as "The Future is Not Set" and "There is No Fate But What We Make." They are utensils in a sense: one spoon shape is wrapped with barbed wire while the handle, a plastic vial, is filled with rice.

To this reviewer, Mann's most thought-provoking work is a furniture piece entitled Vanity. The vanity is a metaphor for the bridge between personal reality and cultural reality. It was inspired by Robert M. Persig's novel Lila: Inquiry into Mortals (New York, 1991), an examination into the culture of the '90s, in much the same way that his earlier book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance looked at the '70s. The vanity is a workbench women use for the preparation of participating in our culture. The myths of our culture quality our experiences and Mann uses the vanity "to explore issues concerning the quality of objects and form".

Mann looks at the human condition and implores the viewer to look at and think about both our cultural forms and our human actions. Mann asks us to eat lower on the food chain by reducing the beef in our diets and to strive to eliminate the use of food as a weapon against others. Mann's latest creations are abstract models that encourage a new way for humans to think, act and feel, especially in regard to food, in order to make this world a more peaceful planet. A portion of the proceeds from sales benefit the non-profit organization New Orleans Artists Against Hunger and Homelessness.

Bettina Wulfing is a critic and art historian who lives in New Orleans.

Marginality and Exile: The Work of Stuart Buehler

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, California

January 4 - 30, 1993

by Sophie Dunn

Stuart Buehler challenges and postures Western logic through a reverie and re-creation of plenitude, a voice of limit and infinity, decay and perfume.

As Buehler deconstructs the signs of culture, meaning is discharged, expelled and reorganized, forming a claim to the truth of ambiguity, contradiction and difference. His struggle of and for existence is an incantation of rhythms and pulsions, sensations and feelings, gestures and postures.

Stuart Buehler is a map maker of ambiguity. He prolifically examines, admits and conveys the landscape of authenticity and difference, never occupying or owning the terrain he explores. His is a cartography of notation: "l have been here and this is what I have found." In gestures of both humor and horror, Buehler notes a country, a space between a place of questions without answers.

The January exhibition of small sculpture and jewelry at Susan Cummins Gallery in Mill Valley, California, represented a limited exploration of the extraordinarily prolific nature of Buehler's work. Since 1984 Buehler has mounted twelve solo shows at Jamison-Thomas Gallery in Portland and in New York. His extensive work in painting, sculptural constructions) environmental installations, photography, text, film, and mail art is quite remarkable. Producing within a field of rigorous and obsessive discipline he creates a code, a personal language of the struggle to create meaning within the increasing uniformity of images and information demanded by popular culture.

Initially Buehler was critically classified as a folk artist due to his geographic isolation and direct approach to materials. Next, his limited formal training was used as evidence for categorizing him as an outsider artist. References to art history linked the work to Calder's prints, Matisse's cutouts, and Cycladic effigies. Though these allusions are supportable, Buehler also joins hands with contemporaries who are very much in the mainstream. One who comes to mind immediately is Lucas Samaras, who engages a politics of marginality utilizing formal artistic concerns and a variety of genres.

The experience of marginality and exile, both physical and cultural, is the cogent force of Buehler's work. Its dissidence is one that undermines the symbolic law of cultural order.

In U.S. Treasury, Buehler creates a bone skull and penny neckpiece, a rosary for the postmodern era. I could almost see a junk bond king fondling its pieces while talking on the phone, moving millions of dollars from here to there, emptying the pockets of workers, and filling his own. The piece seems to tell us that traditional institutions and cherished beliefs are decaying; religion and economics are enmeshed. U.S. Treasury could be an icon for a belief system of turmoil and greed.

In Funeral Procession, incised cow bone, ebony, rolls of undischarged caps and stick matches, some with their tips painted over, are combined to develop an obscure psychological narrative based perhaps on the death of Buehler's signature hanging man. (This is a stick figure whose reality is one of limitless possibility one whose reality is not unlike something imagined, like Robert Musils's The Man Without Qualities.) The piece's visual disunity within a matrix of rhythms and repetitions leaves the viewer unable to touch anything concrete; it taps a moment before meaning.

Stuart Buehler is an artist with qualities. He is a creator of his condition.

Sophie Dunn is a writer and poet living in Mendocino and Bolinas.

California Metal

Hearst Gallery, Saint Mary's College

Maraga, California

January 16 - February 28, 1993

by Mija Riedel

California Metal at the Hearst Gallery in Moraga, California was the ambitious effort of two curators from the San Francisco Bay Area to introduce the general public to the wide range of metal work being made in the Golden State today. Marvin Schenck, curator of the Hearst Art Gallery at Saint Mary's College, and Colleen Schenck, metalsmith and Education Director at the Richmond Art Center invited forty metalsmiths to participate in this exhibit, which was unveiled as a broad survey of the assorted metals and techniques being used by contemporary metal workers for diverse reasons and to multifarious ends. Planned to coincide with The Year of American Craft, California Metal stressed the experimental, innovative attitude which characterized much of the jewelry, sculpture, functional ware and furniture on display.

The exhibits included so many different kinds of metalwork that the three small series of pieces by Abrasha, Lorene Anderson and Marilyn da Silva were a welcome opportunity to see at least some of the artists's ideas developed a bit beyond a passing introduction. The Devil's Garden by Oakland artist Marilyn da Silva was one of the most interesting and animated pieces in the show. A collection of seven hat pins standing ten to twelve inches tall and made from copper, steel, lead, wood, gesso and colored pencil, the spiky variations-on-a-theme stood upright, planted in a straight line like so many carnivorous or poisonous flowers, in a fabricated copper base. Lorene Anderson, also of Oakland, was represented by a collection of five anodized aluminum bracelets, each one a unique, colorful synthesis of a rough, weighty cuff with spiraling, slinky-like ribbons which snaked above and around it. Five square brooches by San Francisco jeweler Abrasha, each measuring 2 x 2" and made from combinations of sterling silver, 18k gold, stainless steel, plywood, diamonds and rusted steel were included from a series of 100 such pins, designed to explore the creative potential of stringent limitation.

More traditional steel-working techniques were embodied in three, Zen-like paperweights by John Fick, the forged steel furniture of William Roan, and the eloquent Seamless Hollow Form by C. Carl Jennings. Jennings's raised, forged steel bowl, set on its own horseshoe-shaped "pedestal" was a fitting reference to the artist's personal history as a third generation metalsmith and to historical metalsmithing in general. This bold, sensitive piece was a pivotal one in an almost overwhelmingly diverse collection. "I like to think of myself as a pretty good problem (sic) solver," Jennings's statement explains ingenuously, "and working with steel in the weights that I do creates a lot of problums."

More experimental materials and techniques were represented by David LaPlantz of Arcata, whose Cactus Cup, 1992, was fabricated from painted aluminum, wood and plastic, and Sandra Vandermey of Sylmar, whose battery-operated, 4 x 6", Capturing the Neutrino Brooch hangs on the wall when not being worn. Thomas Brown's Light Table, 1992, combined cubist characteristics of two dimensional artwork with the tangible qualities of steel, glass and fluorescent light. The materials themselves seems the impetus for Harriete Estel Berman's Patchwork Quilt, Small Pieces of Time and Idols of Generations, Illusions to Prophecy. Judith Hoffman's arguably non-functional Spectacles for Seeing Stars metaphorically summed up the new ways these artists and curators were asking their audience to look at metal work.

The exhibit also included the work of four enamelists, Colette, Deborah Lozier, Marianne Hunter and June Schwarcz, each with a very distinct approach to the medium. Lozier's alluring, poetic pendants look like ancient neckpieces rescued from the jewelry box of Scheherazade. They were suspended in a narrow glass case which allowed the viewer to see both of the elaborately worked side of each piece. In the same display was Japanese Palimpsest, a 24k gold, palladium, anodized niobium, 14k gold and onyx neckpiece by Florence Resnikoff, and two pendant brooches by Judy Bettencourt.

While the Schencks focused almost exclusively on metalsmiths whose work is media-specific - i.e. metal is paramount to what they do - in an effort to recognize the gray area which joins metalsmithing to other art forms, they purposefully included a few artists who might be regarded as sculptors or mixed media specialists first, and metalsmiths second. Self Portrait C by Carl Dern and ?Como? Flecha Amarillo by Lynda Watson-Abbott stretched the definition of "metalsmithing" into the realms of sculpture and mixed media, respectively.

The ninety-three piece exhibition included many of the talented metalsmiths working in California today, although the northern half of the state was highlighted and there were a few unfortunate omissions such as Valerie Mitchell and Mark Bulwinkle. Well-known and respected artists were included along with newcomers; the scope of materials, techniques and artistic objectives was impressively wide; and the exhibit was thoughtfully backed up with three workshops at the Richmond Art Center and a panel discussion at Saint Mary's. It was an industrious effort to educate viewers and fill the void of metalsmithing exhibits.

Mija Riedel is an artist who resides in San Francisco, California

Loma Negra: A Peruvian Lord's Tomb

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

October 13, 1992 - July 3, 1993

by Jamie Epstein

More than 1,000 years before Inca craftsmen fanned the fires in their furnaces with lung power instead of bellows, Moche metalsmiths were forcing their breath through similar long blowtubes placed among the burning coals. More than 1,500 years before electricity had been harnessed, the Moche had ingeniously devised a method of electroplating copper so it shone with the brilliance of gold.

As Loma Negra: A Peruvian Lord's Tomb clearly shows, the Moche, a coastal people who inhabited a 250-mile stretch of northern Peru from about 100 to 800 A.D. pushed the metallurgy envelope. Expanding on the technique of finessing hammered sheets of gold into finery, the Moche elaborated on the quality and quantity of designs and created objects in low relief and three-dimensional sculpture; their technological repertoire also included lost-wax casting and the alloying of metals. As their aesthetic concerns encompassed the contrast in tonalities among copper, silver, and gold, they deftly joined them into a single ornament by edge welding, crimping, and tabs, then added garnishes of spangly disks that moved freely to capture light and enhance the radiance of the metals.

It was this preoccupation with all things golden that must have inspired the experimentation that led to their amazing feat of gilding copper. According to Heather Lechtman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this is how they may have achieved it: Gold was dissolved in a mixture of water and corrosive minerals (salt and potassium nitrate were locally available), to which was added a compound like bicarbonate of soda to create an alkaline pH of about nine. A clean copper object dipped into this solution became both anode and cathode, which supported an electrical current, and when the object was boiled allowed it to be coated with the thinnest layer of gold. The object was then heated to between 500 and 800 degrees Celsius (932 to 1472 degrees Fahrenheit) to permanently bond the gold to the copper.

But this stroke of nearly alchemical mastery would not have been possible had the Moche not already demonstrated their mastery of irrigation. For by coaxing the arid valleys into yielding a bounty of crops, which were augmented with the rich stores from the sea, the Moche flourished. Not unsurprisingly, the tremendous wealth generated by such ingenuity was concentrated in the hands of a few individuals, whose material acquisitiveness supported skilled craftsmen and encouraged innovation. And it is from the nosepieces, earflares, pectoral disks, belt finials, headdresses, insignia, and other regalia accumulated by the elite throughout their life and taken with them to their death that archaeologists have gleaned part of the story of the Moche people.

What we know about the particular lord whose, literally, buried treasure is on display at the Met is that he was the Imelda Marcos of nosepieces. These decorative coverings for the lower half of the face hung from the septum and were worn only by men. The lord governor's oversize collection ranged from naked sheets of usually silver or gilt-copper to those embellished with a simple geometric pattern of raised dots to those that reveal the dominant role animals - from crayfish to iguanas, spiders to bats, owls to foxes played in Moche mysticism.

In fact, animals held such powerful sway - owls, for example, because of their prowess as hunters - that they graced nearly every ornament. The other most frequently expressed motif was the image of the Decapitator, consistently depicted as a fearsome male figure with feline eyes who seems to be coming right at the viewer holding a tumi, a rounded ceremonial knife, in one hand and a severed human head in the other. If a cartoon bubble were to come out of his mouth, it would simply say, "Aarrgh!!" No one needs a caption to deduce the reverence he inspired or to understand his function in ritual sacrifice.

The details of Moche religion and spirituality remain largely a mystery, but their jewelry provides the outlines of a complex culture animated by a supernatural cross-pollination between man and beast as well as the all too tangible fact of being a warrior people intent on solidifying their earthly presence. And although the luster of more than half of the pieces in this small exhibit is obscured by encrustations of algae-like corrosion, what cannot be obscured is that this ancient people transcended the technology of their time to fabricate sophisticated metal objects that have survived to tell the tale of their virtuosity.

Jamie Epstein is a writer and editor residing in Manhattan.

Peter Chang

Helen Drutt Gallery

Philadelphia, PA

November 4 - November 28, 1992

by Bruce Metcalf

There was a time when American metalwork was characterized by excess. Bob Ebendorf used to conduct a surface embellishment workshop, which was a high-energy, rapid-fire presentation of dozens of ways to decorate a surface, and he used to employ about half of those techniques on any one piece of jewelry. Al Paley's stunning pins and neckpieces set a standard of magnum opus metalsmithing for a decade. In the early '70s, the Museum of Contemporary Craft even mounted an exhibition that took baroque excess as its theme, but no more. Alter several waves of European good taste have rolled ashore, and as a modestly upscale marketplace absorbs the energy of more young jewelers, over-the-top excess has fallen out of fashion. Only a few brave souls - Richard Mawdsley, Judy Onofrio, Marjorie Schick, and Ira Sherman among them - continue to violate the canons of good taste by adding too much of everything.

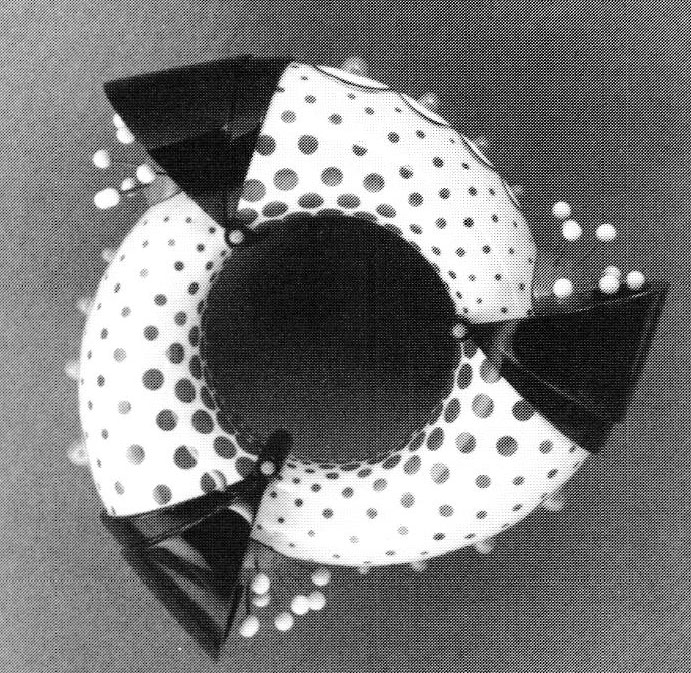

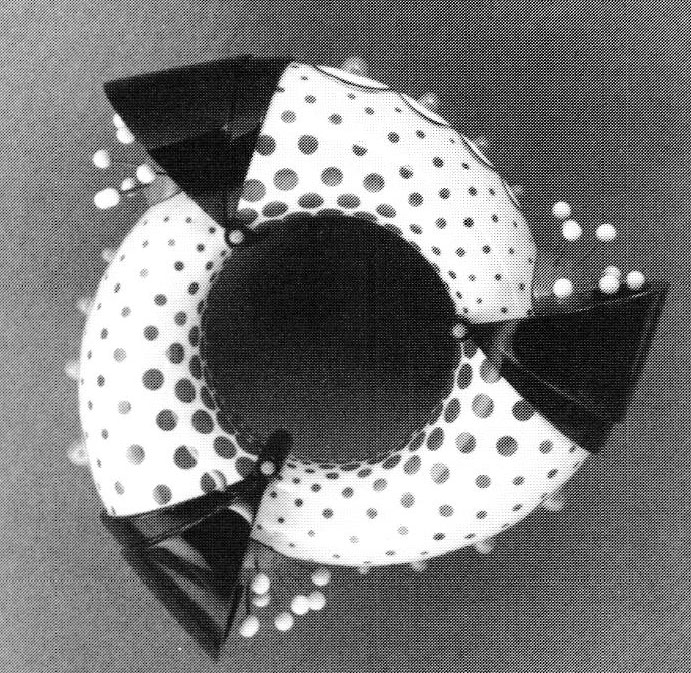

In this environment of retrenchment and restraint, Peter Chang's marvelously excessive plastic jewelry is truly refreshing. While he makes earrings and pins, his large (6″ to 8″ in diameter) bracelets are by far the strongest work. He starts with a carved core of polystyrene foam, which is encased with many layers of brilliantly colored polyester resin and, occasionally, formed acrylic sheet. In spite of their size, the bracelets are very light and surprisingly wearable, as well as durable. The forms are bulbous, sometimes vaguely mechanical and sometimes insect-like. Colors are usually highly saturated primaries, often played in opposites like purple against yellow, or red and yellow against blue. Primary colors are complemented by occasional pinks and mauves. The net effect is reminiscent of the psychedelic posters of the late '60s. Only flashing neon could create more jangling, high-volume color.

The riotous color is balanced, on consideration, by a series of wide-ranging references. In some areas, Chang applies irregular layers of three to five colors, and then polishes back through them to create dot and wave patterns. This is a version of "kasane nuri togidashi", a polishing-out technique of Japanese lacquer work. The reference grounds the bracelets in a deeply traditional craft form, and contrasts with the obvious influences from kitsch, Pop Art, and psychedelia. In other areas, the plastic is carved into faceted forms that clearly refer to precious cut gemstones. Earlier works were surfaced in patterns of tiny fragments of plastic, recalling Byzantine mosaics.

But the present day remains insistent. Chang's bracelets are faintly absurd, being high-craft objects made from a material we commonly think of as worthless. Of course, plastic jewelry dates back to the Art Deco period, but it was not until artists like Gijs Bakker and Fred Woell started using Plexiglas and found objects in the late 1960s that the tactic had a critical message for the art-jewelry world. For those who wished to reject tradition, the employment of junk materials was a radical position. Nowadays, as the American studio jewelers tend increasingly to use gold and other precious materials, perhaps Chang's reiteration of old insights is still relevant. After all, the community continues to insist that the added value of art-jewelry consists of the artist's intelligence and skill, not the material. Ironically, the considerable labor required to construct the bracelets makes them fairly expensive, and only wealthy collectors can afford them.

As the radical gestures of the '60s and the failed revolution of the "New Jewelry" of the '80s gradually become frozen into history, it is a great pleasure to see a jeweler who trades in excess. Fortunately, the initial shock of seeing these things is not empty. Chang's bracelets are also ruminations on traditions of craftsmanship, on the surprises and absurdities of the modern world, and on some of the ongoing debates in the jewelry community. It is equally pleasurable to see such intelligence compressed into jewelry.

Bruce Metcalf lives, works, and writes in Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Metalsmith ’95 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

John Prip/Jack Prip: Arrangements of Changeable Form

Metalsmith ’87 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

Fads and Fallacies: Post Modern Collection

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.