Metalsmith ’93 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

24 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1993 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Mary Rogers, Daniel Waverly Eaves, Jenny Chun, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Introducing New Gallery Artists

The Sybaris Gallery

Royal Oak, Michigan

July 25 - August 29, 1992

by Jo Ellen Stevens

The Sybaris Gallery presented works by its newest young artists in a summer show of metalwork by Daniel Eaves and ceramics by Taylor Bradley and Karen Sullivan.

Summer gallery fare is frequently easy to digest. This season's offering celebrated life and granted a reprieve from taking ourselves too seriously. Consequently, the eight works by Daniel Eaves used familiar objects and themes with humor and a touch of romance to invite viewers to honor the common heroics of ordinary life. Eaves, a native of the rural South, lauded his cultural and historical roots via his choice of ordinary objects, fitting materials, and relevant techniques; yet there was neither the maudlin nostalgia nor the selective fundamentalist prescription that regularly pervades this type of folksy art. Any values proffered were simply portrayed as a tribute to the people of this unique area; they were not served up on the altar of correctness.

Eaves use of the domestic object (i.e. kitchen appliances or utensils) shifted from the usual contemporary feminist strategies to a perhaps radically "new" nonsexist position: the common ground of equal gender usage. In the two coffee sets entitled Last Drop and From The Mountains, the functional object percolates in its "self-ness" and a phenomenological exploration of coffee, pot, and cup. Maxwell House and Folgers brand cans supplied the artist with contemporary materials, a visual bite familiar to every grocery's customers. These printed labels, transformed to appropriate decoration, brewed poetic justice to the art of advertising. The playful use of hole-punched cans for the basket and colorful jam jar tops for the stem's base, produced an uncanny effect upon lifting the lid of the coffee pot. The artist's research on and use of traditional tinware forms and techniques, such as turned edges and lapped and tin soldered seams, imbued the artwork with historical presence and authenticity.

The daily ceremony of breakfast was awakened in Contempotin by the provocation of a tin plate auto-drip coffee-maker. The coffeemaker wore the serious architecture of industry: shiny tinplate, sleek form dotted with pan head screws, a heavy utility cord with a three-pronged plug, and a perforated aluminum sheet used for the water pour and basket areas. The integration of industrial material and methods stressed the work aspect of the auto-drip. The beverage labored from this appliance is a strong cup; no demitasse dessert brews allowed!

Also keeping with the kitchen theme was Juicer. This appliance comported a monumental stance as it tiptoed on little plastic orange refrigerator magnet feet, wearing "TreeSweet 100% Orange Juice" labels around its midsection and a shiny white ceramic squeezer hat. Eaves replaced the original electric cord with one fittingly colored black, yellow, and orange. The pop rivet and tab construction added to this operable Sunkist Juicit contributed a frivolous humor.

Departing from the playful arena, the final works in the show reaped a respectful tribute to the Southern farmer. Three jewelry boxes miniaturized the structure of the rural landscape. In Corn Cobs and, Corn Harvest, small scale versions of two styles of corn cribs fulfilled their function as storage containers. The jewels they contained were not only precious corn seed and dried cobs but equally valuable tools of the harvest: a tiny tractor pulling a four row corn planter and a combine with a harvesting head. Both implements were intricate sterling brooches. In these pieces, Eaves effectively cultivated a reverence for the work and tools of agriculture and their products. Another jewelry box was the charming How Sweet the Sound. A replica of a Southern Baptist church, this musical piece played the hymn "Amazing Grace" when the roof/lid was lifted. The empty interior reflected the individual quest to satisfy one's inner spiritualism.

Jo Ellen Stevens is a metalsmith and writer who resides in Ohio.

The Integrity of Metal, I, II, III

Ag47 Studio Gallery

Seattle, Washington

July - September 1992

by Ron Glowen

A major purpose of the three-part group exhibition The Integrity of Metal, at the Ag47 Studio Gallery in Seattle, was to raise awareness of the metal arts in a community already highly regarded for its active and diverse visual arts scene. Despite the presence of noted metalworkers in Seattle - John Marshall, Mary Lee Hu, Candace Beardsley and Kiff Slemmons to name a few - public interest in the medium seems to take a back seat to other "hot" crafts such as glass or ceramics.

In addition, The Integrity of Metal was promoted as a showcase for emerging talents. Assistant gallery director Gina Pankowski, with colleagues Cynthia Schlemlein and Virginia Causey (all metal artists), assembled the work of about 35 metal artists recently graduated from the University of Washington or the Pratt Fine Arts Center workshops.

Aside from the usual categorical arguments (is it jewelry or small sculpture?; metal artist or artist working in metal?; precious object or product of esthetic investigation?), it is safe to say much of the work was made to be worn as the condition of its public display. Nevertheless, it looked good, of course, in display cases or on the shelves. Wearable art is greatly affected by the personality of the wearer, which sometimes overpowers the creative statement of the object's maker. To counter this, The Integrity of Metal suggested that viewers look at formal and process-oriented factors rather than function. Thus, the guiding sensibility of the exhibitions was to encourage the examination of works as "small sculptures" and pure design.

Yet, the idea of function still lurked as the context for much of the work. Approximately half of the work featured was wearable ornament. Architectural and domestic objects which included grilles, lamps, tables, and vessels, etc., made up another sizable portion of the three exhibitions. The remainder of the three shows was comprised of a few pictorial or image-bearing wall pieces and small objects with a more sculptural intent, though, even these works, often included some consideration of function and/or wearability.

I'm willing to tip my hand, and declare that I look for meaning over issues of making in art. And while I'm not unsympathetic to the challenges of technique and material manipulation, I'm not well-versed in it. Mastering a high degree of technical difficulty is worthy of congratulation, but it does not strike me as the "raison d'etre" of art. On the other hand, it must be noted that Seattle is fortunate to have such metal art experts as Marshall and Hu, and their influence (in terms of technique and design) on students is evident in this show.

Large group shows also tip the hand of the reviewer. The works one selects to discuss or mention may be exceptions to the general tenor of the show, or they may only reflect personal taste and judgment. With the wide artistic and technical range presented by 35 artists, I feel inclined to simply point out the works that attracted or intrigued me the most.

Marilyn Smith's brooches, shaped like boats seen in rushing perspective, often illustrate themes From the history of art. Horace Luke's pins depict whimsical little vignettes from everyday life. Jenny Chun's fabricated sheet silver "containers" feature ingenious clasps and moving parts and the works are either simple blocky forms or miniature objects, i.e. Dirigible.

Gina Pankowski makes jewelry with movable elements - tubed, sliding channels for gemstone settings or metal shapes that are in continual, asymmetrical movement. Judith Laub's more abstract and somewhat fetishistic works incorporate tubular and semi-cylindrical elements of silver and copper with bright and matte patinas.

On a larger scale, the work of Erik Bilello and Steve Northey reveal architectural or industrial metaphors. Bilellot gate of hand-forged iron in a woven pattern of pointed arches and spike blossoms, which includes a tympanum rendered in a design of receding, ascendant perspective, could easily be integrated into a private villa or church. Northey's torched steel-plate table, with an etched glass top, is painted with oil pigments to mimic weathering or patina. It is an elegant "work-shop" piece.

Functional furnishings or vessels by Lynne Hull, Cynthia Schlemlein and Pamela Harlow unite metalsmithing's ancient origins as the material for useful implements with a contemporary designer's sensibility to form and tactility. Hull's "uncoiling", stemmed drinking cups and elegant, slender torchère lamp of patinaed copper are succinct contemporary design statements. Schlemlein's chased silver, holloware pitcher melds a biomorphic look with a machine esthetic, lending an intimate sense of feel to the "anonymous" modern object. Harlow's lantern forms for the garden, modest and simple, seem intended for a tailored Japanese landscape.

Some works suffer from the syndrome of too much experimentation, not enough restraint. Given that this exhibition is mainly comprised of work by emerging and young artists, this probably reflects a case of artists not yet having found their sensibility or direction. I hope. Fetishistic agglomerations and multi-stepped techniques may be rewarding to artists, in terms of process, the intimacy of making, or perhaps these things even have therapeutic value; but it's usually a mess to look at and to figure out.

Whether The Integrity of Metal will elevate awareness of the metal arts in Seattle cannot yet be measured, but it is certainly a step in the right direction. Perhaps it will take continuing efforts, such as yearly surveys or exhibitions curated with an eye toward selected themes, content or context, to bring metal art into the orbits currently enjoyed by other craft-oriented, media-based arts in this town.

Ron Glowen is an art critic based in Seattle, and teaches art history at the Cornish College of the Arts. He is currently editor of the Glass Art Society Journal.

Silver Jubilee

Artspace: A Gallery of the John Michael Kohler

Arts Center, Sheboygan, Wisconsin

August 7 - October 4, 1992

by Michal Ann Carley

Silver Jubilee is a salute in honor of the 25th anniversary of the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. The artists featured in Silver Jubilee all have the earmarks of sophisticated technical proficiency and many display their ability to design elegantly and/or sensitively. The strongest works, however, use their formal language to connote or evoke something more personal or pertinent than simple formal investigation. The works by Robert Joseph Farrell are some of the more outstanding examples of wizardry with materials that do not simply dazzle the viewer with technical virtuosity and display. Toss V Salad Set's evocative surfaces (sterling silver, hollow construction and die forming, copper, brass, 18k gold, hammered inlay) confounds the utilitarian mandate of its title and form. The hammered inlay of the handles suggests both a process of accretion and disturbance that has evolved temporally while the swirling patterns and coloration of the multiple metals reference the decorative mottling of Gustav Klimt's painted surfaces. This fascination with layering and the backwards and forwards of process is conveyed with wit and beauty as one uses the implements to "toss the salad."

Paulette J. Werger also draws from an evocative relationship with the earth's history. In Charm Bracelet and Fish a polished circular cuff of silver doesn't complete itself but is closed by an angular zigzag of gold. Lathed onto the circle with delicate bands is a cast pewter form. Its surface is irregular and densely grey and its abstract shape conjures a mystical fish, canoe or similar talisman. The juxtaposition of the precious with the mundane, and the rigidity of contrived geometric lines connecting to natural biomorphic shapes convey an interdependence of humanity and nature.

Phone Fear (sterling silver, copper, stainless steel, drawing on Mylar, Plexiglas) by Bruce Metcalf is an acerbic lampoon of our tendency to signify inconsequential aspects of daily existence. Just as commercial television ads which display our fears of possessing dirty collars, halitosis and tacky clothes persuade us that we are inadequate, Metcalf pictorially exaggerates our social anxieties and illustrates just how wretched our everyday life may really be. The brooch shows a metallic, histrionic woman, articulated in jutting, running triangular shapes as she is overcome by the act of talking on her telephone. This vignette takes place on an "artfully" colored backdrop of an interior in isometric perspective, adding to the claustrophobic disproportion of the banal act.

The fabricated silver and animal antler that comprise the Double Blade Brooch by Vickie Lee Sedman is a merger of the inherent beauty of materials and the provocative power of the force from which both humans and animals have evolved. Double Blade Brooch has two expanded blades advancing in divergent directions but held in common purpose by the curvilinear elements of silver wrapping around and caressing the antler handle/shaft. The male deer's antler, used to attack, defend and attract other deer is both a symbol and an instrument of power. So too has the design and use of the curved blade functioned for humankind. The size of the brooch is large and its symbolism is overt, thus, it functions as a heralding device like the peacock's plumage or a Renaissance gentlemen's augmented codpiece. In elegant simplicity Sedman unites the rigid and the malleable, the natural and the fabricated, the animal and the humanmade, attesting to those forces that can be at once both erotically alluring and destructive.

The focus of this exhibition is to feature works made of silver, or those that look like silver. Apart from similarity in "metal and/or color," as stated in a press release, the criteria for the selection of the objects is not forthcoming, especially considering that the exhibition presents works made by 31 artists with equally as many different personal expressions and concerns. Generally speaking, the fact that the works are made of silver or look like silver is of little consequence to most of the pieces. Although the quality and craftsmanship of the works are of high caliber, this is not exceptional in a field that is characterized by artisans with advanced technical and aesthetic training. Yet, an exhibition cannot demonstrate continuity of concept nor can it adequately display and juxtapose the works of various artists without a carefully delimited focus. The Art Center is generally known for its consistent, high quality strongly thematic yet pluralistic exhibitions. Thus, one would expect that Artspace, the Kohler's sales gallery, would likewise present engaging exhibitions that would stimulate dialogue and enthusiasm within the field. No art center would be taken seriously with an exhibition of "paintings or things that look like paintings" and such an approach to the exhibition of metals does little to advance the field.

If the field as a whole, including individual artists, collaborative teams, critics, workshops and educational institutions, have aspirations to be mainstreamed into the broader critical art arena, then it is necessary that the exhibitions be directed, focused and acute. Artists do indeed need sales rooms, but they also need exhibitions which contextualize and explain their achievements in forms, materials and ideas.

Michal Ann Carley is an artist, art critic and Associate Curator at the UWM Art Museum at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Recent Work of Mary Rogers

Creative Metalsmiths Gallery

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

September 1 - 30, 1992

by Barbara McFadyen

To transcend the boundary of jewelry as mere adornment is the challenge of many metalsmiths. Creating personal works that will evoke emotion and make a connection with the observer is often the aim of this type of self expression. The work of Mary Rogers featured at Creative Metalsmiths Gallery exemplifies this motivating force. "Putting the mark of the human hand on a piece, this is what elicits a human response and makes a connection with the viewer. Just as native man was compelled to leave hand prints of pigment on rock, the mark of the maker allows for connection of one to another," states Rogers.

The 21 pieces highlighted in this show are works in several different series with an overall sensibility that indicates the artist's attunement with Japanese culture. The visual juxtaposition of powerful broad architectural strokes and delicately detailed interior canvases draws immediate attention to this work. The movement expressed in every piece is lyrical; as the quality of each stroke is like a crescendo and the interiors float on the supporting bars of their musical theme. A counterpoint of textures, granulation, and calligraphic markings characterize these inner "plates." The interplay of chased and scribed symbols is as expressive as the many musical themes and voices of a symphony.

The artist's background in drawing and design is particularly evident in her Collage Series. Shibuichi, fine and sterling silver, and 22k gold comprise the materials of these spontaneous sketch like brooches. A vivid contrast of colors from a blue green patina on shibuichi, to the white of fine silver, to the intense yellow of high karat gold provides the surface upon which mysterious markings are left like footsteps in snow. Dotted lines, triangular motifs, scribed hieroglyphic slashes reap, pear throughout these works; the results of a desire for direct, immediate expression.

The Kimono Fan and Standing Kimono Series present works in similar materials with an oriental theme. Here, the architectural lines are reminiscent of gateways of Shinto shrines. Rogers, who has always been drawn to Japanese culture, began studying the history of kimonos ten years ago. The structural form of the kimono provides her with a perfect format for the formal presentation of textures and patterns. In Standing Kimono Series Brooch #16 the woman's chrysanthemum pattern is manipulated in silver, then banded and tied in 22k gold. A rhodolite garnet adds a strong central focus against the vertical folds bordered with bright blue shibuichi. In the fan brooches, it is the outer framework, whether open or partially closed, that provides the basis to interchange the canvases and challenge the maker. The aerial quality of these works is also visible in the Calligraphy Slash Series. With the upward sweep of bold arched strokes, the experience is almost like that of a kite. Once again the fabric stretched upon this framework is uniquely detailed in a playful and personal manner, yet reminiscent of ancient cultures.

The Amulet Series Earrings present a slightly different format. Moonstone, onyx, chinese turquoise, and carnelian elongated drops are richly combined with wrought 22k gold. These pieces are intended to be badges or talismans something that is personal that also becomes personalized by the wearer. Through this relationship, the piece and the wearer become one. "I am not a 'cutting edge' fashion jeweler, I have always been more focused towards that which is classic and can remain for many years," stares Rogers. "I hope the pieces I make are well designed yet personal so that they will have enduring qualities and be able to grow with the wearer."

As we enter the 90s, a return to realistic values is apparent. People are recognizing quality substance and function over bizarre and esoteric nonfunctional formats. The strength of Ms. Rogers' work lies in the fact that she is not only deeply involved in each piece but that she is equally concerned with wearability. This jewelry in this exhibit is exceptional on many levels. It is deft in its workmanship, dramatic in its use of color and surface and powerful yet intimate in scope. Following the movement and inner detail of ancient themes, this work can become a spiritual journey for the viewer's sensibilities. Such is the mark of Mary Rogers.

Barbara McFadyen is a metalsmith in Chapel Hill, NC.

Souvenirs of New York: Jewelry and Objects Inspired by the City

Aaron Faber Gallery, New York City

July 1 - September 4, 1992

by Lanie Lee

Just as the diversity and density of Manhattan can become overwhelming, so too can an exhibit of works by 25 artists using souvenirs of NYC as a theme. The exhibition at Aaron Faber Gallery offered a hodgepodge of themes and styles that ranged from the abstract to the narrative, and while most of the objects were jewelry there were also wall pieces, flatware, clocks and vessels. Although the majority of works were placed in display cases in two rooms on the mezzanine level, other pieces were displayed in the jewelry store on the main floor and some were in the display case facing the street. As a result, it was often hard to determine what was actually a part of the exhibition. The seemingly haphazard placement of jewelry pinned to gray-clothed boards in display cases and the scattering of objects on the walls in between the cases detracted from both viewing individual works and viewing the exhibit as a whole.

It came as no surprise that the dominant images in the exhibition were the skyscrapers that have made the city both the concrete jungle of the nation and the architectural role model for other U.S. cities. The concentration of skyscrapers on the island of Manhattan has captured the imagination of many in the past and continues as a convention in this show. The cool, sleek vertical lines of these urban monoliths seem particularly compatible with much contemporary jewelry design. In Neopolis, a bracelet by ROY, simple straight-edged geometric shapes cast from sterling silver were linked together, building by building, to create a cityscape. A wide band of smooth silver denoted the outline and varied heights of the midtown skyline. Its jagged edge resembled a crown - a majestic yet detached symbol of the city. ROY also exhibited a number of sterling sliver and oxidized brass pins, depicting building facades and titled East Village. In some of the pins brass steps led to nowhere in particular. Perhaps these pins referred to the ongoing controversy of gentrification that has plagued the neighborhood for years. ROY's designs simplified the complexity of the city revealing a beauty often overlooked or taken for granted.

New York City's architecture was also the motif for a set of 10 anodized aluminum containers called Table Tower Vessels by Anne Krohn Graham. These freestanding three-dimensional structures, with areas painted with grids of color, formed a whimsical group. As space is always a precious commodity in NYC, some of these vessels served double duty as vases or flatware containers and they also had compartments that pulled out into either napkin or candlestick holders.

The sidewalk was clearly the inspiration for Chris Darway's bracelet, composed of rectangular sterling frames filled with concrete and embedded with images synonymous with the city. The piece recalled an aerial perspective of New York. Darway successfully alleviated the normally weighty feel of concrete and silver by including light-hearted images on the surface pushing the hardness of the miniature pavement to the background.

Since the Statue of Liberty is probably the single most-used image for souvenir items, it seemed equally appropriate as the inspiration for works in this exhibition. Linda Kindler Priest used different profiles and views of the statue's face to make sterling silver pins that were studded with either opal, lapis, garnet, or pearl. Ms. Liberty also appeared in sterling silver flatware pieces by Susan Provda.

Though displaced people tend to be an eyesore to many (whenever there is a convention, the homeless become targeted for removal), for Antonia H. Schwed they became the focus of two well-conceived pieces. In a mixed-media wall piece, Vietnamese Veteran Living in the City, Schwed used a box with variously sized compartments to narrate her theme. Within each compartment were fragments symbolic of the vet's experiences. Objects such as heads, figures, a fetus and a door represented aspects of both the physical and the psychological life. This collage left a jarring imprint and represented an aspect of the city that few dared to address in an exhibit of this nature. The other piece, a small figurine of a black male wrapped in a colorful, elaborate cloak, calls to mind those fragile statuettes that line souvenir shop shelves. Made of enamel, copper, and clay this piece, Little City Prince had a fairy-tale aura to it. Perhaps it was Schwed's way of restoring dignity to those that have been stripped of it. These works confronted a social issue that many would like to forget in an environment that oftentimes seems to be an escape from the reality of the city.

Lanie Lee is a writer and editor residing in New York City.

A Sterling Exhibition

Pritam and Eames Gallery, Easthampton, NY

May 23 - June 30, 1992

National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN

July 12 - September 6, 1992

by Bernard Bernstein

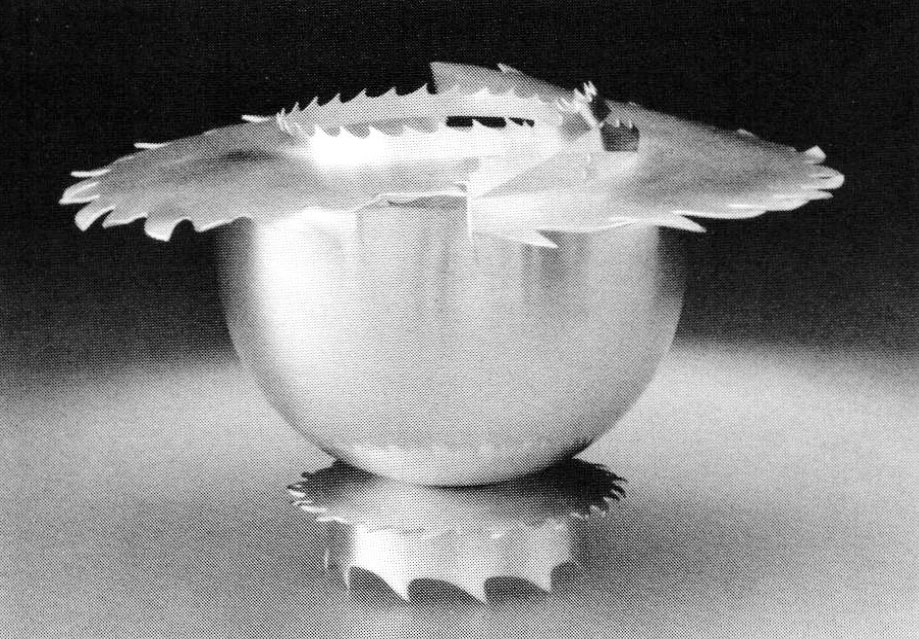

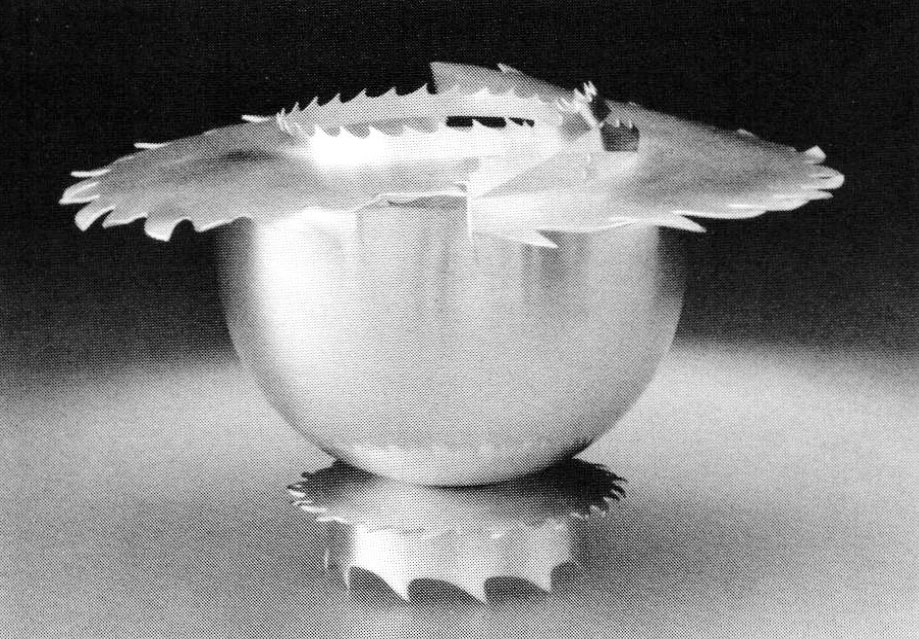

Pritam and Eames has established a reputation as a showcase for fine contemporary handmade furniture. In recent years it has also featured summer exhibitions of hollowware, jewelry, and flatware by America's top metalsmiths. This summer, for the first time, the gallery exhibited work by members of the Society of American Silversmiths. Thirty-eight members submitted a total of 120 objects to the show. About 75 percent of the work can be classed as hollowware; the rest is flatware. Most of the work in both categories reveal by their design that the artist paid primary attention to the requirements of function as well as aesthetics and personal expression. In the minority were unequivocal sculpture and, for want of a better term, "metaphors," objects that relate to some functional ancestor but, because of their design or structure, indicate that if an attempt were made to use them, they would not work well if at all. They also suggest stories or messages that cannot be read easily just by looking at them. An example is Susan Ewing's work, which was visually exciting and technically impeccable. I sensed that there was a personal message in the menacing saw teeth of her fruit bowl. Later I learned that there was - she had experienced a near-tragic accident with a bandsaw.

A traditional approach characterized the technical processes used by most of the contributors. Raising, forging, repoussé, mokumé, married metals, texturing and casting predominated. The use of nonmetal materials such as stones, wood and bone was also traditional but not very abundant. One exception was John Marshall's combination of silver and acrylic. Marshall's adventurous willingness to break with tradition in these spectacular containers was also evident in the way his working of the materials resulted in their visual and tactile expressiveness.

The range of skill levels was quite wide. Most of the objects were very well made. A few, because of such problems as firescale, poor fit and finish and flawed solder joints probably should have been held back by their makers (this was not a juried show). One surprise was, in the case of two or three artists, seeing different objects by the same person span the range of technical proficiency.

Among the pieces I stayed with longer were Sue Amendolara's anthropomorphic decanter; Bob Oppecker's raised, sectioned and reassembled containers; Randy Stromsoe's perfectly executed architectonic punch bowl; Jeff Herman's elegant and simple sculptural centerpiece bowl; Leonard Urso's two deceptively simple, textured and repousséd fine silver bowls; Harold Schremmer's vase, a marriage of control and spontaneity; and Ron Pearson's forged, structurally innovative candleholders. William Frederick's pair of vases announced the hand of a master silversmith.

Robyn Nichols submitted several hammered and chased serving pieces which identify her personal attachment to the leaf and tendril motifs reminiscent of Art Nouveau. Michael Banner also displayed stylistic consistency in his ultra-streamlined, long-handled tea and coffee service. There were also some "fun" pieces, such as Elizabeth Nutt's tic-tac-toe game, Robert Davis's "spinners" and Joseph Brandom's ball-and-bowl game.

I have felt for a long time that a potentially rewarding territory for metalsmiths to explore is liturgical work, so I was happy to see the Jewish ceremonial objects of Ori Resheff, Kurt Matzdorf and Fred Fenster. Tom Markusen's tall candleholders would look at home on a church altar, and Michael Brophy's four-piece christening set showed his technical perfection learned while at school in England.

Silversmiths represent a minority in the metalsmithing community and exhibitions like this do not appear very often. The Society of American Silversmiths and Pritam and Eames Gallery are deserving of commendation for helping keep alive what seems to be a fading art.

Bernard Bernstein is a metalsmith who lives in New York City.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Fads and Fallacies: Post Modern Collection

John Prip/Jack Prip: Arrangements of Changeable Form

Judging Juried Exhibition

GZ Art+Design 2003 Spots

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.