Metalsmith ’94 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

41 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1994 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Nancy Worden, Jonathan Bonner, Betty Helen Longhi, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nancy Worden

William Traver Gallery

Seattle, Washington

April 1 - May 2, 1993

by Matthew Kangas

While Pacific Northwest art jewelry is known for its use of found objects, some artists, like Nancy Worden, tend to surround such items with elaborately crafted casings of cast silver. Instead of working with Northwest jewelry godmother Ramona Solberg, Worden studied under Funk Art advocate Ken Cory at Central Washington University in Ellensburg before doing a graduate degree with Gary Nofke in Athens, Georgia. As a result, there is a loose, slumpy feeling to her pieces which accentuates their humor and narrative quality while giving the illusion of more informal, easy-going construction.

Each of the ten one-of-a-kind pins at William Traver used an eyeglass lens as a window into some symbolic or nostalgic container. The irregular ovals perfectly suit her deceptively casual arrangement of other elements and act as a compositional focus. With a marvelously broad range of subjects, Worden suggests that art jewelry can carry aesthetic content dealing with memory, society, psychology, and even politics at the same time it pleases the eye - and wearer.

The power of time and the ubiquitous character of everyday political symbols are two keys to the dreamy, remembrance-of-things-past quality in her works, Runnin' Yo Mama Raged, 1992, with its Roman-numeral watch face, and in Broken Trust, 1992, an elaborate necklace wherein each eyeglass lens covers a presidential face cut from U.S. currency. Three of the lenses on the necklace are cracked, symbolizing the broken promises of American politicians over the years. Garnet and malachite connectors intervene between George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and the others. Heavy nineteenth-century Victorian jewelry is evoked as easily as the message of political disillusionment is conveyed.

Quick Fix, 1992, makes another point about American reluctance to face problems head on. Aspirins and decongestant pills are encased in a bifocal lens which is surrounded by silver arms grasping basic 'tools' such as a safety pin and pliers. Visions of television nonprescription drug advertising, among many other things, are humorously summoned up.

Also at the humorous end, No More Bad Haircuts, 1993, encases a lock of hair and a tiny diagonal sawblade beneath an oblong rutilated quartz. Over and over, Worden seems to remind us of the follies of our self-reforming vows, both as individuals and citizens. Resolution to Lose, 1992, has silver teeth above popcorn kernels, spoofing every overweight person's determination to eat lots and lots of popcorn as a low-fat 'treat'.

Overprotective Impulse, 1993, turns serious with a tiny silver padlock and chain over a folk-art painting reproduction of a baby. In this work, and in More Home Repairs, 1992, Worden draws our attention to issues of domesticity and the perils of child-rearing with gentle, witty warnings.

With their folksy interpolation of found objects, ingenious variations on the eyeglass motif, and sparing use of stones like onyx, citrine, amethyst and pearl, Nancy Worden has created the equivalent of a collection of short stories about a lost, rural America. Like southern writers Peter Taylor and Eudora Welty she lulls us into a sense of superior appreciation just as we recognize that we, not her 'characters', are the indulgent targets of her sympathy.

Matthew Kangas, Seattle art critic and curator, has written about metal artists Phillip Baldwin, David Smith, and Louise Bourgeois.

Urban (G)litter

Aaron Faber Gallery

New York, New York

July 6 - August 28, 1993

by Lynn Brunelle

You love it. You hate it. It's vast and varied. It's wild, wacky, full of sharp-edged indifference and ironic humor. It's romantic and beautiful. The city is a mosaic.

The urban landscape is the basis of inspiration for 15 artists in the invitational show called Urban (G)litter, organized by Patricia Kiley Faber, at the Aaron Faber Gallery 666 Fifth Avenue, New York.

It is not difficult to be enthusiastic about this collection of viewpoints forged, folded, and fabricated out of metal. To walk through the gallery is to be rattled by the variety of 15 unique urban experiences. The inspirations come from girders, maps, taxicabs, guns, stop signs, and Lady Liberty herself. Each piece has a story of its own.

The Statue of Liberty is the inspiration for Ms. Firecracker, a whimsical cosmetic brush by Susan Provda. The piece raises questions about connections between surface and facade and the deeper implications of beauty and freedom. Its spunk and wry wit, achieved through the collaging of cast sterling objects is reminiscent of Fred Woell's work.

Boris Bally's muse is of a more base and elemental sort. Bally's use of discarded street signs and pieces of rusted metal married with precious metals figures prominently in a compelling group of works exploring urban decay and industry. His Large Shield Earrings - oval-shaped pieces of rust with precise sterling rivets - evoke a sense of tribal simplicity. These are particularly interesting because although they look primitive, they are constructed of man-made materials that are slowly being reclaimed by nature. The pieces conjure up tensions between a pre-industrial and modern society.

Rusted metal is not the only industrial inspiration for Bally. His Trussware series of utensils in the form of clean, sterling girder beam is a marvelous homage to structure. These pieces are disconcerting and beautiful as they link faceless industry with an act as intimate as eating.

Another highlight of this dazzling city tour is the elegant sweep of curves in a sterling bracelet by Peggy Eng. It explores the quiet, spiralling grace of a phone cord. This is perhaps the most understated of the group and it allows for a lovely moment of respite in an otherwise highly charged show.

Jennifer Burton's Late Night Menus brooch reflects a familiar city experience. With the title stamped into it, this brooch is fabricated from sterling, brass, copper, and 14k gold, and peppered with amethyst, green tourmaline, and pink tourmaline. The very essence of this piece suggest nothing so much as a late night Chinese food binge.

With its landscapes, personal experiences, intimate moments, wonderfully whimsical objects, elegant whispers of design based on industrial lines, and found objects metamorphosed, Urban (G)litter is a dazzling kaleidoscope as vastly varied as the city itself.

Lynne Brunelle is a metalsmith, writer, and editor. She lives in New York City.

Jonathan Bonner: Inversions

Peter Joseph Gallery

New York, New York

May 13 - June 19, 1993

by Jaimie Epstein

In mathematics the word "elegant" is used to describe an exceptionally creative proof of a hypothesis. It is also the adjective that springs to mind upon taking in the sweep of Jonathan Bonner's Inversions at the Peter Joseph Gallery. And it is no paradox that the word so easily crosses the boundary between art and science and becomes part of the language of either field of study, for it is the dialogue between these seemingly polarized disciplines that Bonner would have us entertain.

It is also no paradox because Bonner takes his inspiration from mathematics and topology, from Klein bottles and Möbius strips, both of which toy with the concept of surface. As if there could be any doubt about the seed of Bonner's artistic curiosity, he has said: "Each piece consists of a form that reverses on itself, turns half inside out. The outside form is a continuation of the inside form, inverting at the bottom. The inside becomes the outside."

Patinated copper is the medium for Bonner's surface games - for playing with principles of physics, biology, geometry, and mathematics. His sculptures challenge our perception of the physical world, shake us out of the safety and complacency of thinking that what we see is all there is to see. Instead of the modernist: "what you see is what you get", Bonner gives us the opportunity to see more and therefore get more, to peer over the edge of our reality to find that even if the Earth were flat, we would not fall off. There is no edge, no end to the form, for in the beginning is the end and in the end is the beginning.

Bonner's grandfather was a glass blower, and although Bonner eschews topology it's hard to resist making the leap from a youngster's fascination with a mass of molten glass becoming a goblet, for example, to the principles of topology: "Studying those properties of geometric configurations that are invariant under transformation", as Webster's Ninth puts it. In addition, his microbiologist father's preoccupation with exploring the elemental substances and forms that are the basis of life seems to have provided Bonner the substance and form of his own artistic journey.

The Mobius strip that Bonner makes of science and art couldn't be more clear: one tiny sculpture is, in fact, a representation of a molecular form Bonner père is working on. Yet, the spatial gymnastics of other pieces demand further investigation, as spheres, cones, cylinders, football, torpedo, and hot dog shapes interconnect, forging the inner and outer surfaces of one another so that the truth of the concept can be fully comprehended only by peering inside or underneath.

Francis Bacon said: "It is an easy passage from miracles of nature to miracles of art", and while miracles of nature evolve over geologic time, miracles of art have no less arduous a birth. Why should the viewer expect to be spoon fed along the road to epiphany? Bonner's sculptures offer not only an aesthetically delicious meal for the eye but also dessert for the mind - with the added bonus of finally understanding those multidimensional graphs of time and space that made no sense in high school.

Jaimie Epstein is a writer and editor who lives in New York City.

Carolyn Morris Bach Zodiac: Celestial Beasts

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, California

May 3 - 29, 1993

by Matthew Kangas

What can an art critic writing about jewelry do when Carolyn Morris Bach says, "I don't think it [jewelry] is art. I think it is a craft and should be pursued as a craft." Just what does that mean? Even though she won a 1984 NEA fellowship, apparently Bach contents herself with the parallel-but-equal status of craft at a time when other artists are falling all over themselves trying to attain art's greater recognition and credibility.

Given that, it is still this critic's right to judge her work as art - and as craft. With an elaborate cover story in Ornament (Spring, 1993), it is also a little hard to take seriously Bach's claim to a Rhode Island journalist in another article, "One thing I don't worry about is fame." All the same, her Susan Cummins show this spring was a substantial, unified body of work.

Although she told Cathleen McCarthy in Ornament, "Being cute is the kiss of death in the arts" this is precisely the problem she faces in her current figurative work. Yes, the Zodiac is one way of organizing a theme and, in her individual interpretation of the twelve sun signs, Bach has shown great powers of imagination while keeping each figure connected to its recognizable attributes. By choosing to personify the zodiac, she has lent considerable visual interest to each pin.

The only problem is the faces: generic, stylized, and - ulp! - cute. The ironic thing is, everything around the faces is brilliantly conceived and crafted. Fascinatingly intricate, they border on becoming miniature sculptures but, once claimed as such, they suffer by comparison to stricter standards of seriousness.

It seems that the diminutive, the dainty the decorative, and the whimsical are somehow more acceptable in craft, allowing Bach her latitude to sentimentalize and cartoon. Aquarius cleverly sets a pale blue aquamarine at the base of linear silver "splashes" as if the stone were real water. Libra is a companion piece with the same full-length figure having only one arm to hold the scales. Both are enclosed by a loose frame of metal lines.

It's one thing for the symbol-holders to be people but yet another when the related animals are also personified with human faces. Danger: more cute territory ahead. Capricorn has a turquoise in the center of its animal body; Scorpio has a dark blue boulder opal for its body above a little scorpion tail. Even Cancer has a tiny head between two bone, crab claws.

Bach's irregular line bends and curves around all the figures either hemming them in or acting as a formal organizer. The other pins and necklaces are less showy but perhaps more bearable. Twig Goddess uses bent copper as leaves and branches around faces for earrings and a matching brooch. As elsewhere, the laces are frontal, simple, stylized. Since this is a major decorative device for her and, after all, it's only craft, it's hard to be too critical of their repetitive familiarity. Still, one pines for a little more diversity of facial expression among them. We're not talking Modigliani here.

The point is, aesthetic standards for content and technique in craft should be no less stringent than for art. To separate out, dissuade, or demur from joining one category in favor of the other is disingenuous and pretentious. The exquisiteness of Carolyn Morris Bach's technique is laudable; it masks a thinness of ideas and a tendency toward the saccharine that could be avoided had she not insisted upon using the figure. Once that enters into the work, it will be judged like any other figurative work of art or craft: as a commentary on the human condition.

Matthew Kangas, a former Renwick Fellow in American Crafts, is a Seattle art critic and curator who writes for Art in America and other magazines.

Artisans in Silver, 1993

Traveling Exhibition of the Society of American Silversmiths

National Ornamental Metal Museum

Memphis, Tennessee

June 6 - August 1, 1993

by Linda Raiteri

Showcased opposite the entry of Artisans in Silver, stood Chunghi Choo's Peace Lily Vase. It's clean, pure lines were echoed by a freshly cut calla lily placed two feet to its left. Thus, the tone of the exhibition was set.

It is this aesthetic sense, this combination of intuition and logic, which characterizes the installations at the National Ornamental Metal Museum in Memphis. Each piece is given its own space with an awareness of how it relates to and flows toward the next. There are no jarring juxtapositions. Each exhibition forms an organic whole, a completeness.

In an exhibit such as the 1993 Artisans in Silver, which presents the work of 40 members of the Society of American Silversmiths, ranging in tone from the whimsical to the quite serious, this sense of unity is essential. These diverse objects offer images from the ancient to the contemporary, from the sacred ceremonial ware of Kurt Matzdorf to the light-hearted geometric S lice of Life cake knife created by Randy Stromsoe. There is the hardness of the sterling and gemstones Art Deco bowl and servers from Maryland artist Wendy Yothers and the softness of Marilyn da Silva's domed and arched handled Put Out the Fire I, II and III candle snuffers.

Leonard Urso's sculpture of a woman, Sister, and Chunghi Choo's Peace Lily exhibit silver as liquid, as fluid and flowing. A.E. Green combines materials in a set of contemporary wine cups using rosewood and ivory bands to warm the polished sheen of the silver.

At the top of the stairs leading to the second floor gallery is a water kettle with a stand and burner, a traditional piece by Harold Rogovin. In this work, more than any of the others, a narrative is felt. It is elicited by the small heart shape, which is the visual center of the piece, and emanating from that center is a feeling of comfort, of calm, of blessing.

Roger Horner's serving fork, and John Marshall's Markell Vase, are fashioned from sheets of mokume gane with excellent effect. Less polished silver has been used architecturally by Curtis Lafollette in his teapot which looks as industrial as a cappuccino machine and by Jack da Silva in his Memphis style pitcher. This range of works and methods offers a valuable overview of one of metalsmithing's most familiar materials.

Artisans in Silver 1993, a fine collection of works by contemporary masters, travels to the Noyes Museum in Oceanville, NJ, October 17 through December 26, 1993.

Linda Raiteri is a writer who resides in Memphis Tennessee.

Betty Helen Longhi: Liquid Metal

Creative Metalsmiths

Chapel Hill, N.C.

April 25 - May 25, 1993

by Ben Dyer

The metal artwork by Betty Helen Longhi pulsates with a heartbeat of its own. She breathes life into her pieces from her inner world. In expressions that directly portray metamorphosis, rebirth, and the elusive mystery of beauty in nature, Betty Helen Longhi moves nimbly between images that suggest landscapes, sea waves, wind currents, and cocoon forms. Her work implies multi-layers of depth and dimension as a metaphor for Betty Helen's personal and universal statements.

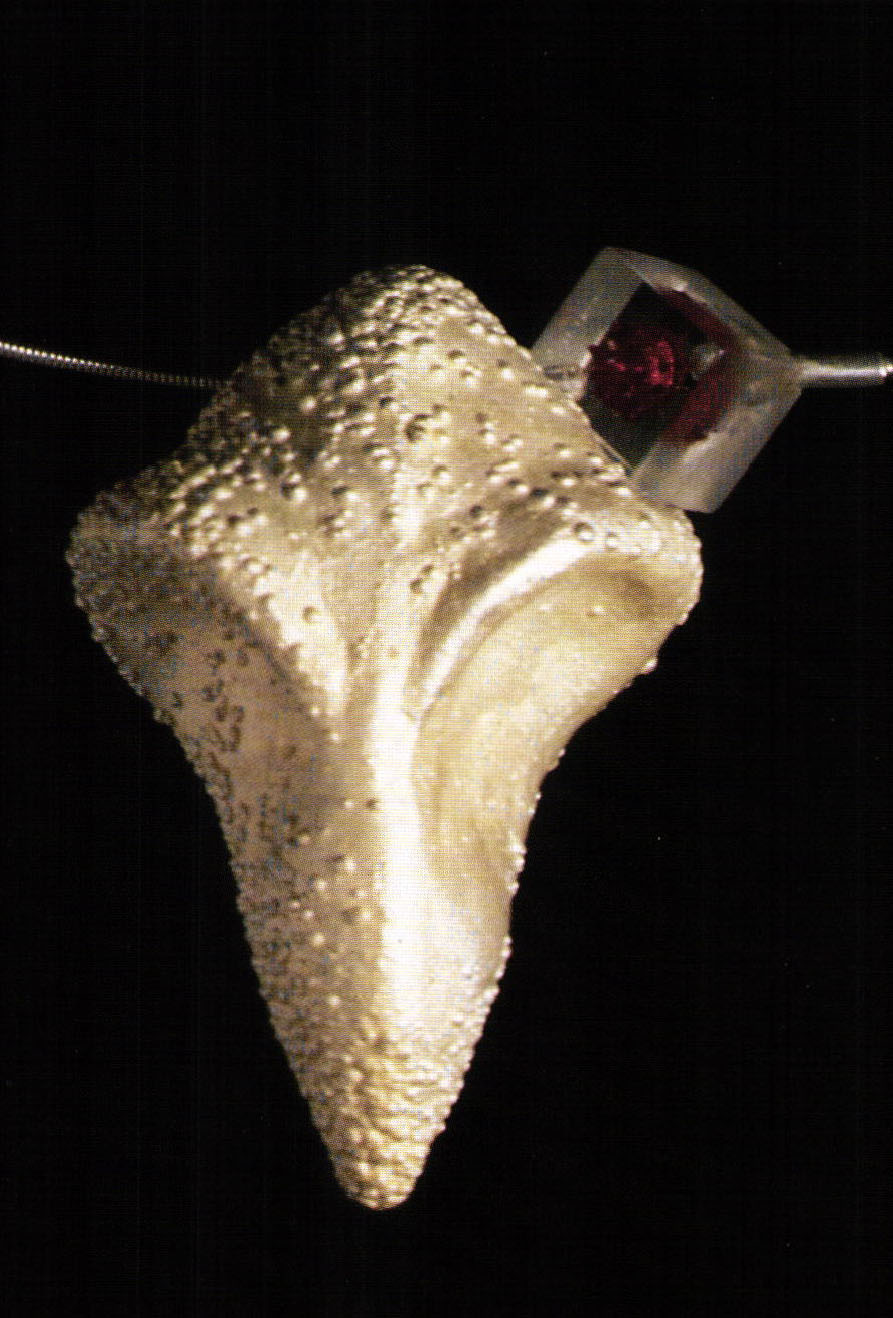

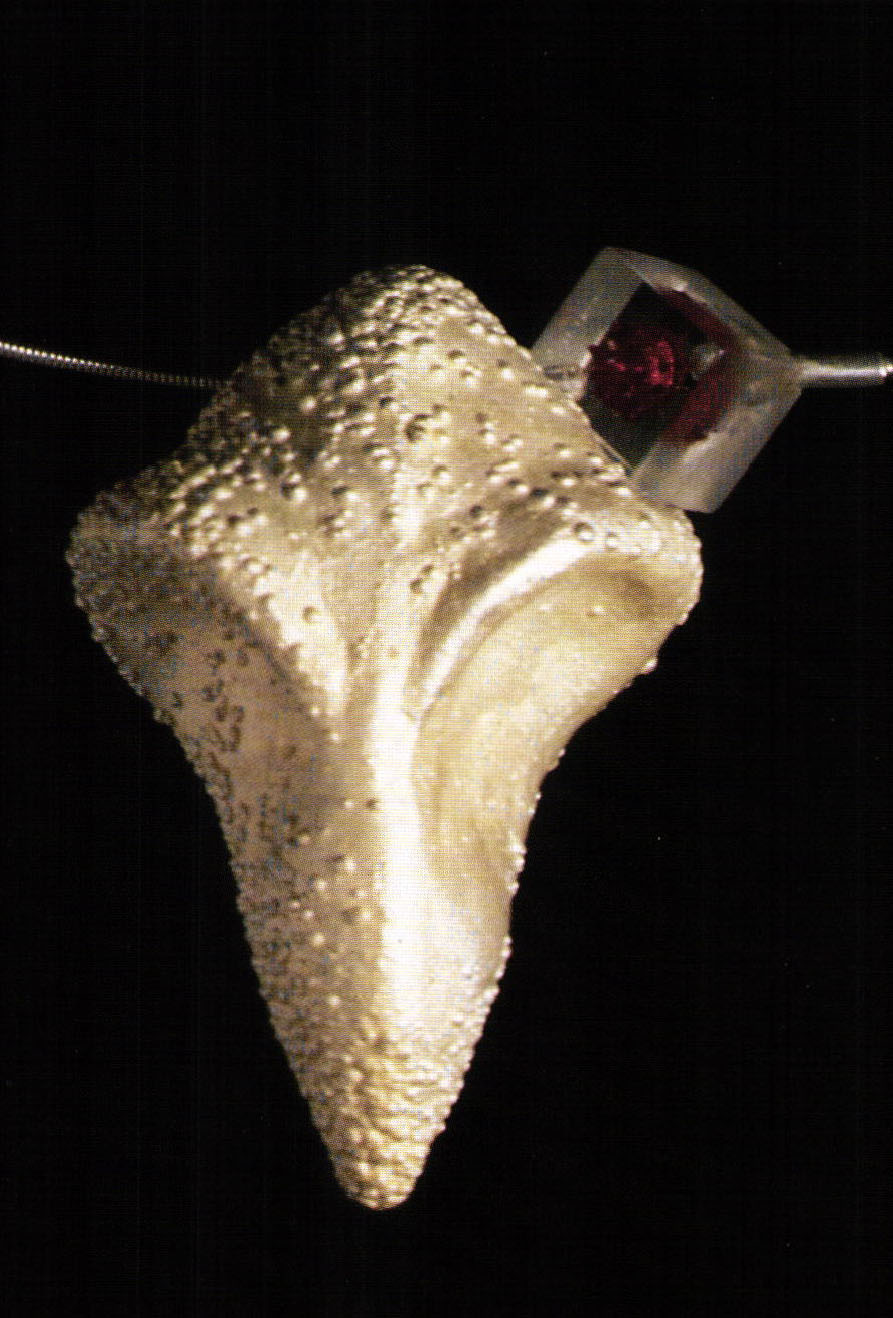

The pendant-brooch, Early Spring suggests an embryo or larva form, waiting, alive with a hidden source of light, a glow that comes from within, having survived the winter. The long Biwa pearl, within the cocoon shape, catches the reflected light and colors of the niobium and appears as a primal yet ambiguous life form: a subtle beauty. "Reflected color is about light not pigment", says Betty Helen. Betty Helen's recent works, Reflections Study #1 and Reflections Study #2, mirror a cool electric color that shines out from their edges and appears to be larger than the pieces themselves. Her Long Pins conjure up images of a double-exposure of waves on the ocean over a landscape of rolling hills and woods.

By a synthesis of her skills and her vision, Betty Helen achieves a mature integration of image, line and texture. She inventively comes to terms with a wide repertoire of techniques, combining various metals, electro-coloration, and finishes into long, fluid three dimensional forms, worked by anti-clastic forming, fold-forming, and forging. She uses thoughtful and playfully engineered connections and mechanisms for her fabrication and jewelry findings. Pearls and diamonds are sparingly used and effortlessly integrated into the artwork, as in her piece titled, Windswept, in which the pearls match the coloration of the niobium. Pieces are often designed for multi-use; pendants convert to brooches; earrings are made in removable layers to be mixed and matched. The fluidity of the images carries through to the changeability of the design and functions of the jewelry pieces. Changeability is about "a line moving through space" and on another level - "A change in time".

Betty Helen's versatility as a designer is evident in her body of work that ranges from small sculptural forms, to elaborate one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces, to her stylish production line of modular earrings, A la Carte, and the convertible series, As You Like It.

Historically, beauty has been associated with the best life has to offer, nature at its highest order, and the intellectual quality that is part of the mystical wonderment and awe of life on the earth. But in our present culture, a study of beauty and grace is not often recognized in the arena of serious art and artisanship as a valid vehicle for new statements. This is probably due to the modern reactions to the sentimentality and romanticism of the Art Nouveau movement and the trivialization of beauty by television ads and commercialism. We live in a cynical time of spikes, razor blades and thorns. Even so, beauty is a timeless quality and grace has a dignity still open to artistic interpretation. We need artists like Betty Helen Longhi, who look to the regenerative energy of the uplifting and positive power of beauty to guide her hammer against the metal, furnish the electric currents that give color, and polish the surface that gives deep reflections.

Ben Dyer makes his livelihood as a goldsmith-artist and lives in the little town of Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Jewelry Invitational

Mobilia

Cambridge, MA

May 25 - July 31, 1993

by Jan Baum

Mobilia gallery hosted its second annual Jewelry Invitational exhibition May 25 through July 31, 1993. The show was organized by owner Libby Cooper and included the work of thirty-six artists the majority of whom are American jewelers. The works included those from prominent artists: J. Fred Woell, Arline Fisch, Earl Pardon, Joyce Scott, Thomas Mann, Colette, Kiff Slemmons, Dan Jocz, Sandra Enterline, and Christina Smith. Certainly any one with an interest in who is making craft today would recognize this familiar roll.

However, the highlights of this show were its combination of newer faces and examples of the use of non-traditional materials. The richness and depth of Kris Patzlaff's jewelry is striking. The work does not demand the viewer's attention but simply beckons and then waits to be discovered. A predominant characteristic of the two dimensional work is their intricately decorative surfaces. They reference pseudo-hieroglyphics, Islamic decoration and computer chips, all of which are visually dense. The shapes upon which these mysterious surfaces are placed are reminiscent of banners, badges, and shields-traditional, information bearing forms. The combination of these surfaces, shapes, and other jewelry-like elements along with the use of oxidized silver, high karat gold overlay, and the monochromatic use of semi-precious stones, inverts one's specific frame of reference into an expansive one. These pieces are immaculately crafted and seem to emanate an overall spirituality.

An unusual highlight in this show was the work of Pier Voulkos. Most of her jewelry exemplified her ability to form polymer clay. Each was made of a necklace, bracelet and earrings and each had a distinct theme. Though I usually turn a blind eye to works of Fimo, one of this series caught my eye. It was based on bulbous plant-like forms. Each piece was made of clusters of bud-like forms striated with color. When worn the beads roll on the body, dancing with kinetic energy. Another series was made of fattened bead-like forms which contained colorful abstractions. Voulkos's manipulation of the polymer clay into volumetric forms adroitly exploits her coloristic abilities.

Many critics have advocated that craftspeople and crafts critics look to crafts history for what is useful, meaningful, and distinct about crafts (instead of looking only to art'). Historically, there are a number of roles that craft has filled. According to Bruce Metcalf in "Replacing the Myth of Modernism" (American Craft, Feb./March 93, p. 44): "Craft objects can stand back and offer commentary, propose reforms, advocate traditions or simply help people get by." Some of these characteristics can be found in crafts today. The work of Patzlaff addresses spirituality and exhibits a high level of technical virtuosity. Voulkos's work functions beyond utility toward aesthetic experiences. Janet Kopolos in "Considering Crafts Criticism" (Metalsmith, Summer 93, p. 10), cites Joyce Scott's beaded neckpieces as a prime example of celebrating "crafts own character". One of the primary functions of Scott's work is that of social commentary which she effects by threading beads into representational stories.

In K. Lee Manuel's work the viewer apprehends the gestalt of the artist's brightly colored and richly decorated collars at once. Manuel constructs, then paints intricate and repetitive patterns and images on collars of feathers. The feather collars allude to the ceremonial traditions of numerous non-western cultures.

The work of James Barker, Judith Kauffman and Luna Felix advocate the tradition of goldsmithing through the use of high karat golds and traditional techniques. Of these, Kauffman's work is the richest. She combines the gold with stunning purple opals and mobe pearls. Her characteristic layering and constructing has a sumptuous quality.

Humor is one way in which the crafts can "help people get by" (Metcalf). Yet, perhaps there should be a distinction drawn between humor and one-liners. The group of rings exhibited by Barbara Walter is a case in point. They are constructed mostly of silver and Plexiglass bands set on ball bearings with extensions of various fabricated objects. One ring titled Bull Only Ring holds a tiny bull extended between two pieces of pink Plexi-glass shaped in the form of bread. The bull rotated around the wearer's finger. This piece along with another titled Pig Out Dinner Ring made me wonder if these were simply one-liners or if the viewer was to derive more significance from these objects. For instance, maybe one would wear the Pig Out Dinner Ring in order to remind oneself not to eat too much; Bull Out Ring would be worn when going to an occasion where there might be a lot of conversational 'bull'. Other visual puns such as Motorcycle Touring and Pussy Footing Around suggest that the intentions behind these works are simply one-liners. Is this humor?

In a show of this scale it is difficult to address the many important aspects of current crafts criticism. Many of the artists' works have a pervading sensibility, that often touches on the whimsical and the fantastical. The selections also show a continued interest in those artists and jewelers who have established their reputations and choose to continue making works characteristic of their signature style.

Jan Baum is a metalsmith who lives in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Dynamic Limitations

Enamelist Society Juried Exhibition

Closson's Fine Arts Gallery

Cincinnati, Ohio

August 12 - 28, 1993

by Janice Hatch-Keaffaber

This exhibition, held in conjunction with the Enamelist Society's fourth convention, was a salute to the diversity and international scope of contemporary enameling. Jurors Harlan Butt, Fay Rooke and Mel Someroski selected 61 works representing 43 enamel artists from Australia, Canada, Cyprus, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Venezuela.

The concept and title of the exhibit were created to challenge the artists, and all of the pieces were limited to the size restrictions of either 6 x 6″ or 12 x 12″. Enamelists who concentrate on panel or three-dimensional formats met the challenge most successfully, not surprising since their work easily lends itself to such limitations. In contrast, many of the jewelers struggled with the presentation of their small pieces, at times resorting to simply mounting them on mats inside frames of the prescribed size, a solution which became a distraction. The often eloquent and jewel-like forms were lost in large expanses of flat background.

Shannon Grant (Canada) and Valeri Timofeev (Russia) flawlessly executed three-dimensional works in traditional plique-à-jour, a demanding technique which eliminates the metal backing to allow light to pass through the enamel. Timofeev's series of six inch goblets and bowls dazzled the eye with intricate wire filigree patterns, capturing the cells of enamel into poetic forms which could have graced the Czar's table. Grant's twelve inch Dagger, t study in light-reflecting transparent blues, offered a contemporary interpretation of the technique, with the knife held by clear glass supports, making it appear to balance on the point of its beveled glass blade.

Carolyn Delzoppo (Australia) turned cloisonné on fine silver into ornamentation for the wall instead of the body. Her 2¼" square pieces were centered in wide black frames, enhancing the subtle shading of black and white tones which were acid etched to a velvet finish. In Miniature III, additional design elements were thoughtfully introduced with fine silver wire, then delicately balanced with a sweep of transparent color.

There were works from the United States that were notable: Audrey Komrad's cloisonné and fine silver foil wall piece, Dreamworld, a lyrical work of precisely controlled sea forms evolving from a sleeping woman; Rita Deanin Abbey's Red and Chrysocolla, a bold gestural statement in porcelain enamel on iron; JoAnn Tanzer's masterful linear abstractions, interactive plays of multi-layered designs.

The exhibition's most exciting work was a three-dimensional table piece by James Doran (Canada). Working in a kind of conceptual realism, Doran used electroformed copper and enamel to create a fool-the-eye, is it enamel or is-it-real tableau, intriguingly titled It Takes All Sorts to Run Away from Home. An enameled red and white bandanna held the runaway's treasures: a school photo thumb tacked to an apple, a baseball card, pieces of candy, a pencil, and a black knight from a chess set. The work teased the viewer on both artistic and intellectual levels, simultaneously generating speculation about meaning as well as technique.

Doran's work was a refreshing departure from the predominately abstract and pictorial pieces in the show. There were only a few other pieces which triggered emotion or thought. Unfortunately, this seems to be a common weakness in most enamel exhibitions. The precious quality of materials and the visual seductiveness of technique and color overpower creativeness of concept or message. Although this was a strong show of consistent quality and the size limitation presented a measure of challenge to the artists, a narrative theme for future exhibitions could encourage an interesting investigation of meaning while retaining the medium's emphasis on craftsmanship.

Janice Hatch-Keaffaber is a writer, enamelist and political activist living in San Diego. She is a frequent contributor to Metalsmith.

From the Fire

Adair Margo Gallery

El Paso, Texas

August 5 - September 17, 1993

by Beverly Penn

From the Fire is a, straightforward exhibition. It features seven artists whose commonality is material and methodology: each transforms metal into art using the ancient rituals office: scorching, heating, burning, melting. Despite the unifying theme, the show is not focused on incendiary fascinations, obsessions, or technologies. These artists are atypical allies, and the thirty pieces assembled by director Adair Margo is one of the most diverse selections of jewelry, sculpture, and vessels executed in America within the past decade.

All of the jewelry in the exhibition is hung directly on the gallery wall, without pedestals, shelves, or framing devices to interfere with definition or assert value. Rachelle Thiewes's five untitled necklaces are long, rope-like, silver loops punctuated at intervals by slender beads and rings of gold, silver, or slate. In the installation "(the) wall is understood as an absolute space, like the page of book. One is public, the other private." Each piece hangs just inches from the bright white wall, suspended from two hooks. Gravity pulls the loops into plunging triangles. Light floods the space. Each necklace is a metallic line. Each shadow is a dense dark twin. The created shadows are as predominant as the necklaces themselves. Light and form are equal. This unusual installation of jewelry does two things. First, the light unifies the five pieces into a single event that is experienced much like a theatrical or musical production. The pieces and their shadows dance like drawings in the wall. Though these necklaces are created from precious materials and are constructed with immaculate technical perfection, both their 'value' and 'finesse' are mysteriously concealed by the bath of bright, white light. The work shuns the pretension and self aggrandizement often suggested by jewelry and is instead a provocative, intelligent statement of light and form.

Second (and this may be the other side of the same coin), because the individual forms are visually dissolved by light the installation supports Thiewes's philosophy that her pieces are most articulate when they are worn, rather than when displayed. The gallery encourages viewers to wear the necklaces, and is accommodating and knowledgeable on this point. On the body these pieces have an unencumbered quality - there are no interfering mechanisms or awkward transitions - and they respond rhythmically to body movement. The final surprise is the subtle but fascinating sound that the pieces make when in motion.

Other work in the exhibition pushes and pulls at the architecture for its definition. Jamie Bennett's wall installations, Red Scroll and Green Ribbon, use vitreous enamel on electroformed copper and oil/polymer on paper. Each of the featured wall pieces balances two parts: a small framed painting and an object on a shelf. They seem of the world but not in it. In Red Scroll, both the painting and the object are each colorful versions of a wilted tendril planted in a sensuous, bulb-like vase. The two-dimensional image is framed in thick, dark wood, and the three-dimensional object is poised atop a heavy ornate wooden shelf. The painting serves as a document of the object, while the object is material evidence of the painting. Everything seems heavily anchored to the wall by the dark wood accouterments. The work is narrative yet cryptic, like an ancient codex or a Japanese haiku. In this posed fiction a dying vine form pushes its way out of the vessel with the energy and solemnity of a monocarpic plant, which flowers and fruits but once in its life: a dramatic fecundity followed by death. The painting of this event is sealed away behind glass, like a preserved document of some historical fact - it seems an ill-timed, impatient, pre-mortem memoir of the dying vine and luscious fruit. Embodied in this piece is that moment between blooming and dying: the dialogue of the two elements is their equivocation of will and fate.

The exhibition features a remarkable range of artists who vary greatly in their creative concerns. Helen Shirk, Thelma Coles, Richard Mawdsley, June Schwartz, and Myra Mimlitsch-Gray each represent equally divergent perspectives in metal. Mimlitsch-Gray deconstructs both the forms and the potential meanings of autonomous found objects. She alters them, then organizes them into four curious, dark orchestrations, Plate Study #1 through Plate Study #4. Cutting daringly and dead-center into the pristine surfaces of antique metal serving trays, she hollows out a shallow niche in which to locate a precious implement, itself a peculiar reconstruction of an antique silver spoon. These silver implements embody both the metaphors implied in the original silver spoon form (sustenance, nourishment, privilege, etceteras) and those new meanings implied by the alterations: the spoons have been cut up, divided, twisted and reassembled into forms evocative of tongs, scissors, or weapons. The niches are precisely silhouetted cavities, referring to reliquaries or sarcophagi. As venerations of time and change, these pieces compress the past, present, and future into a single event. Mimlitsch-Gray's work derives its meaning not from art, but from the richness of material culture. Each found object is obviously altered from its manufactured state through very specific and meticulous fabrication by hand, but the work does not bear the notations of the 'hand of the artist'.

Rather, their technical perfection satirizes the formalist credo which designates the mark of the hand as legitimate voice of the spirit. Laced with double entendre and semiotic inquiry, this work is impervious to formalist criticism, and adds a new dimension to critical thinking in the field of metals.

This entire group of work is shown to advantage in the raw, essential space of Adair Margo's upstairs gallery. The brick archways and the other industrial characteristics of the exposed architecture reinforce the idea of altering space to accommodate an expression, and enhance the structural characteristics of metal as a medium for building, fabricating, constructing, and creating.

- Sol Lewitt, commentary on "Wall Drawings" from the exhibition catalogue Sol Lewitt (New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 139.

Beverly Penn is a metalsmith from San Marcos, Texas. Beverly is also the first recipient of Metalsmith's Annual Award of Excellence in Metals Criticism.

Robert Griffith: Recent Work

Zoller Gallery, The Pennsylvania State University

University Park, Pennsylvania

September 27 - October 31, 1993

by Albert Anderson

Robert Griffith's recent work in copper, wood, and steel seem to stalk the viewer - waiting and watchful, silent, yet aware. They stand guard over the gallery space, evoking impressions of tribal images, totems, and primitive ritual objects. Some are solid and sturdy, others ethereal, almost spidery in their delicate linearity. The scale of the work is vertical and relatively small - from twenty inches to a little over five feet in height.

Several pieces have parts that appear machined to which are attached whimsical, irregular elements in metal and wood, or sometimes simply surface color to soften the geometry. Others are almost completely deformed yet somehow they remain structurally viable. All are immediate in their visual impact. One nominally figurative work, Festiva, combines pipelike cylindrical forms to which a coiled metal rod, raised weld beads, and other elements have been added. The surfaces are adorned with gold leaf, paint and vibrantly colored marks applied with paint sticks and oil pastels.

The works are constructed, for the most part, with familiar metal fabrication processes - raising, forging, forming, welding, and brazing, among others. In Griffith's case, the mastery of these processes borders on the virtuosic. However, the pieces do not flaunt technique. The construction is always subservient to the idea. In many cases, the processes are not apparent, requiring actual handling of the work to identify them.

Griffith, trained primarily as a metalsmith, was for many years a creator of vessels, edged tools, jewelry, and other quasi-functional and decorative objects. On a physical level, those forms are often evoked in the present work, with the addition of imagery of the metalsmith tools he actually employs in making such objects. In this sense, the work is both a record of the artist's journey and the baggage of his creative existence.

The pieces seem autobiographical in other ways as well. One of them, No Moor, suggests a narrative, perhaps of a boat swept away in a storm. Its painted wood and linear elements are reminiscent of fragments, of wreckage - symbols of the fragility and vulnerability of the craft on which we depend to carry us over life's waters. The element of decay, or perhaps more accurately of age, also enters the experience of this work as well as that of other pieces such as I'm Coming Home. The sagging irregularities, the patinas, the blemishes, and the bumps are all reminders of the dents and dings of human experience, of the inevitability of being run over by life from time to time in the course of living it.

One of the most successful works is Sentinel, a forged and fabricated painted and patinated steel sculpture approximately five feet in height. Comprised of three distinct rigid sections, the piece appears to move and sway as it points into the space. There are two contrasting vertical elements. One is geometric. On top, the other more organic form stands in precarious balance. Its horizontal, weathervane-like fin section reinforces the sense of movement with its delicate twiglike wire elements which are reinterpreted in the weld beads on the machined section below.

Griffith's art mirrors and echoes the breadth of the traditions of modern sculpture while going well beyond. Here and there the viewer catches a fleeting glimpse of an image reminiscent of a David Smith, a Beverly Pepper, an Alexander Calder, a Constantin Brancusi, or perhaps even a Martin Puryear. Yet, as soon as such images register they fade. What remains is an original and compelling body of work by a promising young artist.

Albert Anderson is a educator and critic living in State College, Pennsylvania.

Broken Lines: Emmy van Leersum 1930-1984

Museum Het Kruithuis, 's-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands

April 4 - June 13, 1993

(American tour in the planning stages)

by Janet Koplos

One might say that the bilingual catalogue of Emmy van Leersum's retrospective exhibition, Broken Lines, moves her into the realm of myth. As presented in the catalogue she matches, to a degree, the popular-culture stereotypes of the heroic artist: emotionally troubled, obsessed by her work, tenaciously overcoming obstacles, and a career tragically cut short by an early death.

But at the same time, the catalogue reveals her fully, both as an artist and as a human being - more fully than anyone besides her closest associates would have known. Essayists Antje von Graevenitz and Gert Staal have an advantage in not needing to tread carefully around the feelings and opinions of a living artist. While they approach her with sympathy (catalogues are not the place for attacks) they are evenhanded and objectively analytical in discussing her rather late start as a jeweler; her overturning of conventions in form, material and presentation in the early work in collaboration with Gijs Bakker; and her development of an austere, exquisitely minimalistic aesthetic. There is none of the defensive 'special pleading' that mars so much writing about crafts.

One thing that is missing is a picture of the other jewelry of the time, so it's hard to keep in mind how extreme, how unexpected, van Leersum's work must have been. The best a reader can do is measure from her earliest work, the commissioned pieces of precious metals with precious stones. From their conservative elegance, like a slightly icy Art Nouveau, it is a jump to her increasingly Pop neckpieces - simpler, fatter, broader, larger - attached to basic dresses of her design. Those works link timeless shapes to time-based fashion. And it's an even bigger jump to the high aluminum collar that rises up behind the wearer's head like a halo, where drama comes before practicality.

In the retrospective exhibition held in the 17th century armory that is now Museum Het Kruithuis, these pieces from the '60s furnished a lively kickoff for the chronological presentation. But her subsequent jewelry (as well as the sweaters shown in the catalogue) is conceptually more rigorous and so consistently rectilinear that these first works seem to be aberrations. Their primary value may be that they marked the release from convention. It was a less-organic geometry that engaged her from the early '70s until her death, and problems of simplifying, ordering and conceptually clarifying seem to have been her essential concerns.

Gijs Bakker refers to a search for universals and a wish to avoid personal 'handwriting' during the '60s, and both would seem to have been characteristic of van Leersum's work. But it is also possible to see it as a continuation of Dutch abstraction, related to the regularity and nuance of Mondrian and De Stijl, just as it's possible to see those artistic expressions as having arisen from the flatness of the man-made Dutch landscape and the coolness of the northern light. Dutch art and design have tended to rationality more than to expressionism in the whole of the twentieth century, and van Leersum's mature work is very much in keeping with that.

Certain practices, such as working in a series, take on a larger meaning in this context: each work in a series is not simply a practical unit of production but is representative of a conceptual system. Van Leersum designed on paper (or by manipulating paper), and once she had her idea she worked through it in fine increments of variation. Such works as her thin, translucent PVC bracelets with a V-shaped notch stand alone as simple forms given a subtle fillip; but when they are seen in a row in the exhibition vitrines, or with their production drawings in the catalogue, they are revealed to be movements in a progression, each notch being of a different depth.

Some bracelets were conceived on paper as curves plotted through the center section of a square that was divided into three bands; in the finished work, where the plotted lines are absent and the center third is realized as a cylinder of stainless steel, the cuts may look rather free and unpredictable. There's some of that same apparent impulsiveness in brooches and bracelets whose elemental forms are barely disturbed by slices or pinches in the metal, and it is found as well in the overlap in bracelets that consist of a rolled-up strip of acrylic or aluminum. But none of these interventions is arbitrary. Bakker speaks of van Leersum's constant search "for controllable form in relation to the organic field of the human body." Her search was usually carried through all possible permutations of a given problem.

As executed in hard, modern materials, this obsessive thoroughness of van Leersum's makes each work a diagram, a model of intellection that nevertheless results in a surprisingly pleasing ornament. Fortunately, she was not one to be caught in her own success and did not restrict herself to these minimalistic and colorless works. She began to work with color through sandwiching tissue papers or textiles inside thin layers of PVC, and she used strips of nylon of pure blues, reds or yellows to make geometric collars and bracelets that were visually softened not only by the use of color but also by the more flexible character of the material. And in an entirely different direction, her plotted lines on paper seem to have attracted her so much in themselves that she produced a series of bracelets consisting of the intersecting lines alone; in these works she returned to precious metals. In all her work, her dogged pursuit of essences allowed nothing superfluous, nothing gratuitous. How nice it is [or a viewer of this retrospective to see that hard thinking and reduction to basics does not mean the elimination of beauty.

Janet Koplos is an associate editor for Art in America.

Keith Lewis Cutting Losses

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, CA

July 5 - 31, 1993

by Bruno Fazzolari

Jewelry, more so than most possessions, can be deeply personal stuff. By attempting to use jewelry as an expressive and even narrative medium, Keith Lewis effectively explores and exploits the possibilities for private and public experience of jewelry in his recent work at Susan Cummins Gallery.

Most of the pieces detail varieties of grief and anxiety related to AIDS. Their small, rough, iconic nature places them squarely in the tradition of the momento mori, as both expressive vehicles for the maker and wearer. The nature of AIDS and grief is two-fold: public, political anger, and private, solitary anguish. Art dealing with the subject tends to fall to one side or the other of this apparent dualilty. Informed by the fact that grief is one of the most personal and lonely of emotions Lewis's work attempts to be effective and ritually useful, offering the viewer the opportunity to experience his own grief and to 'place' it somewhere. Many of the pieces in the show have private spaces knowable only to the wearer. Just a Few Pricks depicts a bloodied figure stabbing itself with knives. When turned upside-down, the torso forms a cavity lined with soft, inviting silicon textures, hidden among this, waiting for the investigating finger, is a needle.

Lewis's particular brand of figuration escapes the pathetic by invoking the absurd. These creatures, for they are none of them quite human, have the heads of birds with long beaks (or noses) that recall the masks of the commedia del arte, or the characters in "Spy vs Spy" from Mad magazine. As such the figures seem rather hapless and even comical in their misery. But amid the clowning is some serious business. Their comic associations are supplemented by strong associations of form with the mute and proud figurines of Cycladic and Etruscan Cultures, whose legacy is that of mourning and magic. In one pin, Stealing Hair a copper figure is shown taking hair from an object on a pedestal (a museum piece? an altar?). Bursting from its hollow torso are stray strands of hair and on closer inspection the figure proves to be veritably gorged with the stuff. Materials like these are the ingredients of magic and witchcraft. They refuse the category of eternal, static, art object and move into the realms of the crucifix and other fetishes as useful emotional and psychic tools.

Lewis has explored the narrative capabilities of jewelry with fresh results. Six Months Wasted consists of six neckpieces, each holding a pair of pendants: one a sort of star (Lewis's symbol for the virus) encased in plexiglas, the other one, one of Lewis's birdheads/peopleheads. The pieces are sequential: as the virus grows larger the heads become smaller. The wasting of the tide could be a Proustian waste of time (time ill spent in the six months can take to test positive for the virus after contracting it) or it could illustrate the speed of 'wasting', a symptom of HIV disease in which someone loses weight and bulk within a mercilessley short period of time.

In choosing this medium to treat a particularly tricky subject Lewis has created some very direct and witty work which takles the emotional baggage that makes AIDS such an unwieldy subject. There is no pity here, and no whining. Lewis keeps an unsentimental distance towards the emotions and crisises which his figures are engaged in, but somehow their absurdity is not beyond our sympathy.

Bruno Fazzolari is a painter and writer who lives in San Francisco Bay area of California.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Bruce Metcalf: Between Darkness and Light

GZ Art+Design 2004 5 Spots

The Search for Modernist Style Jewelry

Exhibition in Print: Metalsmiths Win The West

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.