Metalsmith ’95 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

29 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1995 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Joyce Scott, M.K. Dilli and Shana Kroiz, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"Wearable Work I" Joyce Scott, M.K. Dilli and Shana Kroiz

Galerie Francoise et ses frères

Brookandville, Maryland

December 1 - 31, 1994

By Julie Flanagan

If color connects the work of Baltimore artists Joyce J. Scott, M.K. Dilli and Shana Kroiz, shown together in a December 1994 show at Galerie Francoise et ses fréres, it is the intent of these three women which divides them. And color is the dominant feature of the sculptural jewelry displayed in the black-walled gallery. Scott and Dilli use beads to develop rich, textured surfaces, while Kroiz combines metal and wood with enamel, hair, rubber, and pearls. Yet, look beyond the color to the intent of the work and the similarities end.

All three artists are technically skilled but they each direct their skills to different intents in their work. Joyce Scott uses beads as the vehicle for commentary, expressing her personality heritage, and political and social views. M.K. Dilli's jewelry designs follow a more traditional, wearable format. The artist collects beads from many sources and the patterns she develops become the local point of each piece. Shana Kroiz creates sculptural forms with figurative and phallic representations derived from ancient weaponry and other influences. Though the brooches are wearable; the three dimensionality and simplicity of the forms allow them to transcend the intimacy of jewelry.

The beaded collars that Scott creates are the most intriguing pieces in the show. Her use of beads of complimentary colors develops rich surfaces alive with visual stimulation. The historical and social references in the work invite the viewer to explore the detailed beadwork to understand the story Scott tells.

Jam is one of Joyce Scott's large scale neckpieces which looked quite different on my second visit to the gallery. The central focus of the piece is a black and white skeleton stretching across the front of the collar. On more careful inspection the skeleton was peeking through open spaces in the weave of beads from the other side, I realized that Jam is a reversible neckpiece, and Scott had asked the gallery to show the other side of the piece each week. It combines large and small beads with glass inclusions made precious by their beaded prong or bezel settings. Iridescent blue and purple beads form the structure of the collar and surround the black and white skeleton. The second time I saw the show, the neckpiece was being displayed, with the skeleton less visible. Thin strands of red beads creep through the open holes of the skeletons face like veins or worms from an underground grave. The juxtaposition of bold, bright colors with stark black and white lend an eerie and intriguing quality to the piece.

In a gallery which shows jewelry only once a year, it is nice to see quality work displayed as fine art. However, the few simpler pieces by each artist - most likely included in the show to garner sales - took away from the work which truly belongs in the art jewelry category.

Julie Flanagan is a metalsmith working in Baltimore and teaching jewelry at the Maryland Institute, College of Art.

William Harper

Peter Joseph Gallery

New York, New York

December 1, 1994 - January 14, 1995

By Karen Chambers

Raw may seem an odd adjective to describe William Harper's work. He is acknowledged as a master craftsman and has the awards to prove it. In his latest work shown at Peter Joseph Gallery, the pieces were beautifully crafted to exploit Harper's chosen materials of gold, glass, enamel, and gems. The physical traces of his fashioning and his manipulation of the metal remain evident, not a lack of finish, but rather a sign of respect for his materials. His choices of eccentric jewels signal a preference for the vitality of the less than perfect, except for this artist the natural is always perfect. The colors of his cloisonné enamels are sophisticated in hue and combination. In Faberge's Seed #6 rust, copper, and alabaster play off of slivers of chrome yellow and a minted emerald. Variation #5 on a Theme by J.J. & E.M. pairs reflector orange with a Tiepolo sky. The compositions are coherent and accomplished even when they contend, as they do in Large Variation on a Theme by J.J. & E.M., with a roughly rectangular plaque of enamel, a gold criss-cross relief, and a faceted amethyst that adds both a circular formal element and a reminder that we are looking at jewelry, not small-scale painting or sculpture in the narrow sense.

For the two series shown in December and January Harper took inspiration from Jasper John's misnamed (as catalog essayist philosopher Arthur C. Danto pointed out) cross-hatch paintings and Faberge's Easter eggs created for the czars of Russia. Nothing would suggest raw as appropriate to describe the exquisitely finished brooches and necklaces of Harper's variations on themes by J.J. (Jasper Johns) and E.M. (Edvard Munch whose Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed features a crazy quilt bearing a resemblance to Johns' own marks) and the "Fabergé's Seed" series. We're dealing with a maker who is extremely aware of the history of the visual arts so he can quote as freely from one of the masters of modern painting - Jasper Johns - as he does from that master of the decorative arts - Fabergé. He also throws in asides from the African and Indian metal traditions and Tantric philosophy.

So why would the first word to come to my mind when I walked into the Harper exhibition be raw? Because these works have a power that communicates as primal and basic. For all of the refinement of Harper's technique, it is never precious; he retains the essential quality of his (may I say?) raw materials. He is not afraid to mate seemingly antagonistic traditions without making them appear at odds. In the Fabergé Seed series, which might be considered an anti-homage since Harper sees it as what Fabergé might have done if he had had soul, the contemporary artist conjures up African traditions and forms. In Fabergé's Ashanti Beads, Harper presents a stunning necklace that might be characterized as a hanging sculpture if the form and scale were not so clearly in the jewelry-making tradition. He has translated the glass beads used by Venetian traders into richly enameled globes of abstract patterning/painting. They are encircled by rich gold work worked in the Ashanti vein, but recalling the mode of embellishment of the Russian source. The wonderfully strange baroque pearls that Harper uses so often also adorn this necklace of hanging charms. Each seems to be an amulet intended to protect its wearer. Each has power. And Harper has multiplied the power that jewelry is expected to project in all cultures in this work by combining cultures and traditions. As far as Harper's contributions to the history of visual arts are concerned, he makes a statement for the '90s when the debate about the differences between art and craft will simply evaporate because the evidence makes it irrelevant.

Karen Chambers is a frequent writer on glass who resides in New York, NY.

Reliquaries and Offerings

College of the Redwoods

Eureka California

October 3 - 28, 1994

By Kris Patzlaff

Curator Jeff Georgantes, brought to the College of the Redwoods Art Gallery, four artists' works which are predominantly fabricated in metal and explore the concept of reliquaries and offering. The gallery was divided between Rebecca Davies, Karen Pierce, Theresa Lovering Brown and Emily Enders Steffian, accentuating the highly diverse approach to the subject matter.

Historically, the role of the reliquary, which took the form of a container, box, or locket type of jewelry, was to elevate objects or relics (often of Christian significance) to a point of preciousness and reverence. Offerings, on the other hand, involve a significant role in everyday life as well as in special religious ceremonies. Both of these concepts involve spiritual inquiry.

Generally the work that referenced the tradition of reliquaries did not deal with actual objects of significance but rather with thoughts, observations, and memories. These receptacles seemed to hide, foster, or revere a personal relationship or memory. The personal nature of these reliquaries had the potential to insulate the viewer from the relevance of the artists' experiences. But while some of the works took the path of obscurity, others beckoned the viewer to become part of the romance. Artists used their private memories as a vehicle for viewers to explore their own thoughts and memories.

Rebecca Davies's large showing of work, included both jewelry and objects. The reliquary Memories was an extremely delicate looking rectangular box that was suspended within an open framework of silver wire. The strength of this visual image elevated the importance of recollections, relating their sometimes fragile yet undeniable ability to suspend time. Here, jewelry brooches and necklaces were commentaries on the collecting of objects as mementos of other times and places and the ability to conjure up remembrances. The series of brooches entitled Suspended Time Series were eloquent statements on the fragility of memories. A structure of silver rods, methodically wrapped with fine silver wire, held protected in its center a suspended, delicate gold organic form. The technique Davies chose to employ in the making of this series reinforces her ideas on how we all deal with memories. The brooches gave the wearer a different perspective from that of the person viewing it being worn: a metaphor for the way that shared memories may be differently recalled.

Theresa Lovering Brown was represented by small sculptural pieces and brooches. This body of work conveyed her in-depth investigation of architectural forms reminiscent of portals, as a formal image to house her more personal inquiries. Through these architectural shapes Brown invited viewers to look at these works as places of meditation or reflection in which to contemplate personal spiritual issues. Haven of Entrapment, Haven of Cogitation, and, Haven of Resolution were three similarly formed pieces but resolved with different surface treatments and variations on incised window-like openings. The formal and technical qualities of the pieces were strong and warranted closer investigation. However, Brown's personal issues were just too personal and in turn, ambiguous to the viewer. In a statement Brown says "… I have only skimmed the surface of what is possible with these special environments". Further investigation into these environments may result in work that more thoroughly communicates these issues.

Emily Steffian's constructed reliquaries of found and recycled objects are ". . . homage's to those people who have shown me how to really see my surroundings". The importance of these individuals was related by Steffian's ability to arrange ordinary, discarded articles of contemporary society into extraordinary objects of visual contemplation. It is the essence of her relationships with these people that came through in her elegant handling of rusted pieces of metal, circular objects of chipped paint, and an old buffer broom. It is not important to know much more about these people; it is enough to see how they have affected this artist.

For instance, Feeder, a construction of concentric circular found objects, centered on a blue circle with an image of a fly, exemplified her minimalist approach to the materials. A small offering cup extended as a separate, but integral part of the piece, was placed at the bottom of the larger circular birds eye form. The functional quality of this bird feeder emphasized the nurturing aspect of her relationships.

Also included were offerings that are presented to various deities by artist Karen Pierce as "… thanks for the magical times I have experienced in our natural environment". The strong visual impact of Pierce's work made me want to return to it and experience it over and over again. This beckoning was commanded not only by the objects themselves but also by the atmosphere they created. Many of the pieces were vessels employing overlapping leaf forms, in which spaces between the shapes allowed light to filter through, creating a pattern similar to that found on the forest floor. This added environmental dimension set a stage for a spiritual interaction with the objects and the understanding of the activity of the offerings. This was further accentuated by removable objects within the works, representing pods or seeds that could be manipulated to strengthen the ritual experience. Throughout her works, pierce uses a simplicity of form that provides a surface which is enhanced with patina and pigmented waxes, resulting in rich colors reminiscent of the earth.

Kris Patzlaff is a jewelry artist and teacher who lives in Trinidad, California.

Silver in America 1840 - 1940 A Century of Splendor

Dallas Museum of Art

November 6, 1994 - January 29, 1995

Milwaukee Art Museum

June 13 - August 13, 1996

Winterthur Museum, Delaware

September 9, 1995 - January 7, 1996

By Matthew Kangas

While most American museums were concentrating on collecting and exhibiting colonial-period silver, seven years ago, the Dallas Museum of Art began buying post-1840 American silver which, according to chief curator Charles Venable, organizer of "Silver in America 1840-1940", nobody else really wanted: too ornate, too garish, in short, too Victorian - judging from the 150 objects on view in the 15,000 square - foot installation at Dallas. Venable and his acquisitions committee were right. Showy, ostentatious, elaborate, and beautiful, Gilded Age silver is a perfect match for Texas where flaunting wealth has never been politically incorrect. In fact, the whole thrust of the show and its 357-page color catalog is to dissect and analyze such extravagant consumption. Venable is Winterthur American material culture program graduate so, for those students of American history, context is all; art status and aesthetic issues are relegated to a history of styles. Rather than retrofitting mid-to-late-19th-century American metals into a revised hierarchy of art status including American craft, the approach has been to uncover systems of production, labor relations, patronage, industrial developments' advertising, working conditions, and, eventually after 1929, decline and decay.

I'm not saying Venable's method isn't the right tack to take; it's just that the requirements for according art status to American metals like silver do not merely involve a history of styles of ornament and decoration. They involve admitting possibilities for the interpretation of meaning on a variety of levels: personal, social, religious, social, and in the case of late-19th-century American silver, patriotic and corporate. No disrespect intended, dear readers, but "silver in America 1840-1940" puts most contemporary metals to shame. True, these achievements were the result of large corporations like Tiffany & Co. and Gorham (as well as smaller firms like J.E. Caldwell, Tifft & Whiting, and George W. Shiebler). They had little to do with the concept of studio crafts as we know it, although the turn of the century saw the rise of Arts and Crafts silver made in numerous smaller workshops. All the same, the degree of exquisite workmanship, amusing or lite imagery, and gorgeously seductive materials do not seem to have been equaled to this day.

The eye-popping caliber of much of this work was directly related to the economic climate of growth and unrestricted consumption which Venable chronicles at length. There were, to be sure, recessions before 1929 (i.e., 1906-7) but, apart from the diversion of World War I, production continued on for years. By the way, many of the major American factories like International Silver Co. and Gorham eagerly turned to munitions at that time and, as Venable points out:

Over the course of the war, Gorham produced munitions for Serbia, France, Russia, Switzerland… [and eleven other countries]. However, in the end, Gorham's expansion into munitions proved disastrous… 'topped off by noncollectible debt of the Russian government'.

Long before that, the sky was the limit. America's robber barons were falling all over one another trying to commission or buy ever more sumptuous examples symbolizing American power, geographical expansion, marital love, and thanks to enormous national advertising and promotional budgets, the concept of heirloom-giving.

Right in the center of the Dallas installation is a magnificent recreation of the dining room seen in the film The Age of Innocence. Part of the insanity of American silver is revealed in the numerous special implements: fish slicers, ice cream knives, ice-water containers, salad tongs, sardine forks, etceteras. The table setting, complete down to the place cards which covered the long table set for 30, is punctuated with gargantuan centerpieces of ornate grandeur, all below a ruby crystal chandelier.

Just off this room, viewers enter an area of stark contrast: the servants' quarters where the silver was polished. As long as one in four U.S. households had at least one servant, (as was the case by 1890) silver consumption rose steadily. By the end of World War I, however, such entertaining was considered unseemly or passé and, as Venable reminds us, regardless of their modernity Art Deco styles and other Modernist variants never captured the public imagination in the same way as colonial-revival. Debutantes were reduce to posing for magazine ads with their bridal silver. According to market research, most American women (the chief purchasers always) preferred colonial-revival, a trend that continues today.

Silver, then, is about recapturing a glorious (if unjust) past, a focus for extravagant nostalgia and outdated paradigms of pre-IRS shopping sprees. Even so, the technical achievements of artisans executing the designs of George Sharp, Edward Holbrook, William Codman, and Edward C. Moore definitely deserve our admiration and respect. At first, mid-19th-contury American silver strove to emulate English and French designs but, by 1880, the tables were turned. America was "the foremost contemporary creator of silverware in the world". Not only were the French and English sputtering about their loss of market share, they were, along with the Russians, copying Tiffany versions of japonisme or other innovative adaptations. All American culture is synthetic of other cultures and, again, even though native American motifs were at one time developed, the fusions and adaptations of European and Asian traditions were always executed with verve, energy, and skill that was uniquely American.

Finally, can the case be made that large commissioned pieces like The Bryant Vase (1875), The Comanche Cup (1873), The Helicon Vase (1871), The Goelet Schooner Prize (1882) and The Nautilus Centerpiece (1893) are the antecedents of American metal sculpture in this century? If the avant-garde had never happened, supplanting as it did silver with steel, bronze, or recycled assemblage junk, then yes. The problem with elevating American commemorative silver to art or sculptural status, either as apogee or forerunner, is that no followers or movements followed it.

Instead, American studio craft succeed the "century of splendor". After World War II, studio metalsmiths turned to jewelry, small-scale sculpture, hollowware, and other, more diminutive pursuits. For one thing, without the manpower resources available to Gorham and Tiffany (which included child labor and seven-day work weeks), no independent artisan could spend the average of two or three years on one piece.

Thus, the achievements in silver (and gold) of the Gilded Age and the (Teddy) Roosevelt years shall probably never be equaled. More to the point, they were collective accomplishments, which were the products of a largely unregulated runaway capitalist economy, unlikely to occur again. On second thought, the way things are going in this country right now, such circumstances could happen again. The question is, would American metalsmiths rise to the occasion?

Matthew Kangas, a Seattle art critic and curator, is Corresponding Editor for Art in America, National Correspondent for Sculpture, and the author of Breaking Barriers: Recent American Craft.

Intimations of Immortality: The Silverwork of Michael Filmus, Judith Filmus Resheff, and Ori Resheff

B'nai B'rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum

Washington, DC.

August - October, 1994

By Bernard Bernstein

This exhibition displays, for the first and only time in my experience, a collection of Jewish ceremonial objects made by a family of silversmiths spanning three generations. The artists are: Michael Filmus (1890-1963), his daughter, Judith Filmus Reshelf (1915-1966), and her children, Ruthie Resheff Lieber (b. 1951), and Ori Resheff (b. 1955). Now that Ori's two youngsters are enjoying bench-time in his workshop we may yet be treated to an even rarer four-generation show in a few decades. In the catalogue, the museum's director, Ori Soltes, eloquently explores the levels of meaning suggested by the exhibition's title and relates them to traditional Jewish concepts of immortality. For instance, parents assure themselves of a measure of immortality through the transmission of physical, spiritual, intellectual, and material legacies to their children. Artists continue to live through their works, which survive them and influence the works of artists who follow. Artists who are also parents enhance their immortality even further when their children and their grandchildren practice the same art or craft. This phenomenon contributes significantly to the unique character of the exhibition.

I couldn't help but notice some parallels in the way I was looking at the creations of this multigenerational family of Israeli silversmiths and the way archeologists study the fragments of ancient artifacts unearthed from the successive strata of past civilizations that underlie the State of Israel. In both cases it is possible to discover evolutions in the use of materials, working methods' aesthetic style, and surface ornamentation. I found it fascinating to trace the changes through the more than eighty years of art work that Ori Soltes refers to as the Filmus-Resheff continuum.

Michael Filmus, already accomplished in several crafts, came to Palestine from Poland in 1911. His skills qualified him well to join the faculty at the recently-established Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem. The primary goals of Boris Schatz, the school's founder, were to develop an indigenous craft industry producing work in many media, to raise the status of craft to that of art (!!!), and to create a national Jewish art style having its own identifiable aesthetic personality. Filmus's work in textile design and silversmithing contributed heavily to what soon became a Bezalel style. That style was a blend of European art nouveau, art deco, and traditional middle-eastern decorative motifs. Subject matter included important Jewish iconography, such as the menorah, Hebrew calligraphy, sunrises, (to symbolize the dawn of Jewish national aspirations), historical sites, which often included local for a and fauna, and biblical and modern heroes.

Filmus's metalsmithing repertoire included conventional forming techniques such as raising and seaming, and decorative devices like beading, dapping, overlay of wire and sawn shapes, filigree elements, and damascene work (inlay). His personal design innovation was the building up of open-work structures by joining intricately-curved fat silver bands. These had the visual effect of oversize filigree and cloisonné, (minus the enamel) with an art deco flavor. He used these units in the design and construction of Hanukah lamps.

Filmus soon left the Bezalel school and, after the end of World War I, opened his own silver factory where he and twenty workers produced a variety of objects, including plates and holloware in brass with silver and copper inlay decoration. This damascene technique, a Bezalel specialty, was brought back to the school by some of its silversmithing teachers who had been sent to Damascus by Boris Schatz to learn the craft.

The business failed and Filmus later opened a workshop in Tel Aviv, where his young daughter Judith, helped produce a line of art and craft objects, and simultaneously received on-the-job training as a silversmith. Some years later, after travel in Europe and work on a kibbutz, Judith returned to Tel Aviv, studied silversmithing, and finally opened her own workshop and taught crafts at elementary schools and teacher seminars. She followed her own path and focused on the making of Jewish ritual objects. The style of her work gradually evolved from one similar to her father's to a more contemporary idiom. Along the way she made use of semi-precious stones, accents consisting of small areas of granulation, and constructions that combined silver with pieces of ancient Roman glass.

Judith's children, born in the '50s, took up the family craft. Stylistically, Ruthie and Ori traveled in opposite directions. Ruthie became involved with richly engraved surface decoration and Ori, after spending his childhood in both his grandfather's and his mother's workshops, became an apprentice in his mother's shop and in the late '70s formally enrolled as a silversmithing student at the stare-run Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. By this time, the modernist esthetic brought by European teachers and designers, such as Ludwig Wolpert and transmitted, in turn by their students-turned-teachers, had replaced the characteristic ornamental style of the first Bezalel school of the early twentieth century.

The look became minimal, functional, unadorned, and in some cases, mechanical, as if produced in a machine shop. Ori Resheff's work has some of the best of these qualities, but he moderates it and imparts his personal stamp by retaining aspects of the elegance and grace of the Scandinavian classics. He creates forms and textures with traditional hammer-and-stake techniques. One texture that may be his personal innovation consists of elongated peen marks that spiral up the surfaces of his hollow forms. He also makes extensive use of the rich red colors of patinated copper elements in combination with silver. I don't know whether these touches are intentional or not, but they do speak to me of the pervasive sense of the antiquity of the Land of Israel that resides in the collective unconscious of its people. Resheff continues to experiment and evolve. Two recent pieces in particular, a Purim grogger (noisemaker) and a Megillah case (container for a scroll of the Book of Esther), made of brass and anodized aluminum in a distinctly Postmodern style, exemplify his drive toward continued growth.

Seeing this exhibition is a rare, rewarding and educational experience. It is going to travel but at this writing a final itinerary has not yet been arranged. It would pay to check with the museum to get up-to-date information on the show's location. At the very least, send for the catalogue.

Bernard Bernstein is a metalsmith who writes about Jewish ceremonial art. He lives in the Bronx, New York.

The Art of Goldsmithing

De Novo

Palo Alto, California

November 19 - December 31, 1994

By Alan Revere

For those who revere fine craftsmanship, this exhibit is a meditation. For those who appreciate originality it is an inspiration. And for those who seek fine design, here is a place to rest and revel. The work of Abrasha, Bernd Munsteiner and Wilhelm Buchert, featured at de Novo gallery cannot but impress those who recognize quality integrity, and vision in contemporary crafts.

Curated by Maria Cristini, the exhibit presented the work of three modern masters whose jewelry shares both kinship and diversity. All three were trained at the famous jewelry school in Pforzheim, Germany. Each has devoted years to study, practice, and perfection. Each has reached a point of limitless self-expression using precious materials as the vocabulary and an artist's mind for the content.

Born in Holland, trained in Pforzheim and living in San Francisco, Abrasha creates jewelry as bold and sleek as a rocket. Combining flawless hard edges with softly brushed surfaces Of gold, silver, and steel, Abrasha employs his enviable skill to create his own brand of stark, dramatic jewelry. Both striking and highly wearable, his brooches, rings, and pendants transport the viewer to a timeless era, where engineering and art find perfection in precious jewels. Particularly innovative are Abrasha's Capsule Pendants in which he uses gold as mechanism and ornament to adorn polished steel cylinders.

Munsteiner! Within jewelry circles and beyond, the name is synonymous with revolutionary gem cutting. Probably the most respected lapidarist in the world, Bernd Munsteiner has put his family's tradition to good use as the source for his artistic statements. A gem cutter since the age of fourteen, Munsteiner was the first to break away from tradition and use gems as miniature optical sculptures. His geometric mirror cuts and sleek fantasies are in a class by themselves. Beginning with gem-quality aquamarine, topaz, tourmaline, ametrine, (a naturally occurring combination of amethyst and citrine) and other materials, he adds his skill as a designer and goldsmith to create jewelry which is collectible the day it leaves his workshop. This warm-hearted bear of a man is as happy as a kid in a candy store - and why not? Having created his own playground, he not only climbs higher than anyone else, but he is constantly raising the bar. Equally devoted to his work is Wilhelm Buchert. Unlike the others, Buchert prefers soft, sensuous, organic forms with a twist of geometry. Like the others, he works primarily in 18k, to which he adds diamonds and other gems, plus his signature accent of platinum wire screening. These little details, combined with contrasting smooth and rough textures are what makes Buchert's work work. Reminiscent of archeological treasures, Buchert's jewels ask to be fondled, worn, and carried away.

If there were ever a testimonial for the argument that technical mastery opens the door to artistic expression, this fine collection of the goldsmith's art is it.

Alan Revere was trained in Pforzheim, Germany after receiving degrees in psychology and fine arts. He is the director of San Francisco's Revere Academy of Jewelry Arts, author of Professional Goldsmith and a member of the American Jewelry Design Council.

Modern Metals: Objects of Contemplation

Main Gallery, University of Texas at El Paso

El Paso, Texas

January 26 - March 1, 1995

By Rebecca Scheer

Taking my cue from the exhibition's title, I walked into UTEP's main gallery to view art I naively presumed was gathered around the idea of its contemplative value. But as the collection and the press release soon revealed, the meaning of the theme of the show was not objects of contemplation in the sense of things to think about, rather it was an attempt to validate the upward mobility of metal work within the hierarchy of the art world. In other words, objects of contemplation means objects worthy of contemplation, i.e., fine art.

The point of confessing my personal confusion is to illustrate an issue often overlooked by exhibiting metalsmiths and curators, the issue of a context (in exhibition) for our individual works, the extension of which affects the context of our collective work in the artistic community. An artist may have various reasons for creating work but the deliberate act of exhibition is the request for a dialog between the piece of work and others. Potential conversants in the dialog should be given a clue, from the title but most importantly from the kind of work represented, as to what the topic of conversation is.

Arranging a show around either the theme of things to think about or the general theme of these things are art is essentially non-thematic and thereby does a disservice both to the individual pieces involved and to the individuals viewing the works. Works shown out of context and actually not given context lose meaning. All the pieces in this show were lumped together under the heading "objects of contemplation" which ignored the various ways the works communicated their content. Certain works which operated on more subtle levels of meaning were overshadowed by works which displayed immediate meaning.

For example, the juxtaposition of works like Harriete Estel Berman's Hourglass Figure: The Scale of Torture with Chunghi Choo's vase diminishes the apparent importance of Choo's work because her work is subtle and formal and the meaning of The Scale of Torture is immediately and socio-politically apparent. The work of Christine Clark, Billie Jean Theide, and Chris Ramsey was also adversely affected by this grouping. Kate Wagle's Vanitas fared better because the meaning is both significant and readily apparent. Art is the embodiment of ideas and in the garden of ideas (exhibition), explicit meaning is picked first. Creating this kind of competition between pieces in this exhibit was not productive. Fortunately, the work of Beverly Penn and Harlan W. Butt shone through the muddle.

Standing eight feet high, Beverly Penn's series Reflections of Venus confront the viewer with images that loom large in women's lives. The patinaed surfaces of these four, fat, iron cut-outs of various depictions of womanhood from Willendorf to Boticelli reflect the age-old objectification of women. The irony reflected in these four mirrors is that this image foisted upon women is two-dimensional, reductive, corrosive, and its reality is ugly. The gilded frames enclosing the women are also an indictment of an art world that has made women into objects (of art) rather than creators (of art). To this reviewer, Penn's Reflections cry out, " We've been framed, girlfriend; now let's make our own images!".

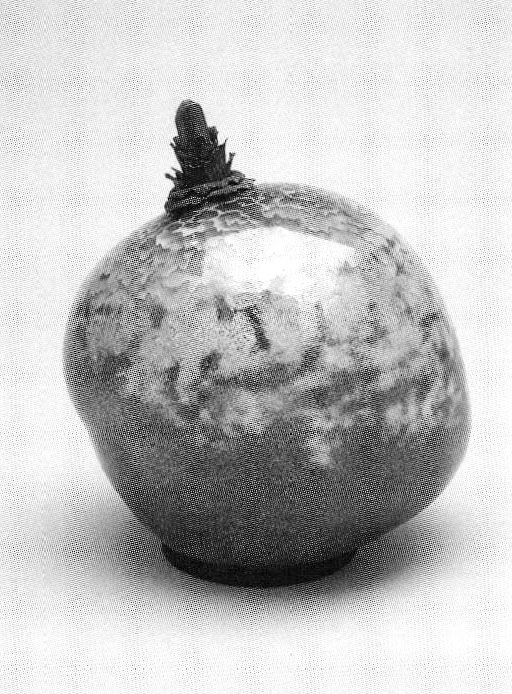

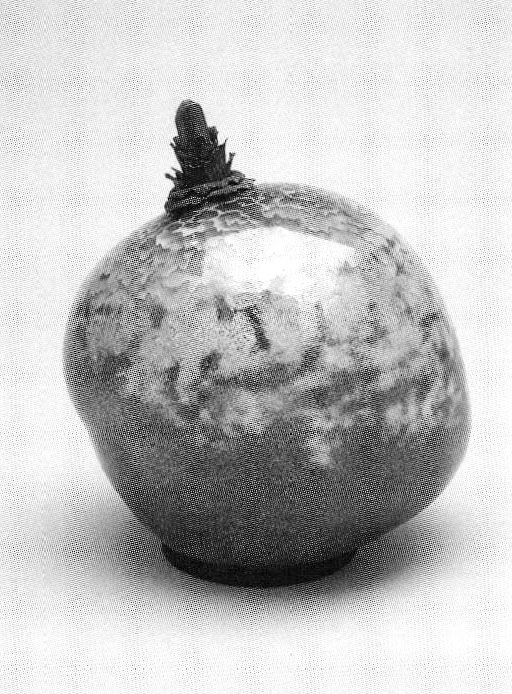

The most intriguing objects in the show were Harlan W. Butt's Garden Anagogies. Webster defines an anagogie as "an interpretation Of a word, passage or text that finds beyond the literal, allegorical and moral senses a fourth and ultimate spiritual or mystical sense". It is indeed hard to find words to describe the quiet aesthetic of the two objects displayed beyond the sheer beauty of their globular forms and enameled surfaces. These works are interpretations, with all the sensuous qualities of fruit, suggestive of all the joyous possibilities of fruition. These are not fruits of the earth but of the imagination, the revealed fruits of patient and exquisite craft.

For all the exhibition's stated intent to include sculptural rather than traditional utilitarian or decorative works, every piece in the show had connections to either or both utility and decoration. This background should not be construed as a weakness but as fertile ground to those who are pushing for the acceptance of metal work as fine art. A better way to give merit to the field of metal art would be to arrange exhibitions that carefully choose and present fine (metal) art with regard to the complexities of the essential meanings embodied in those artworks.

Rebecca Scheer is a metalsmith who lives in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Notable Exhibitions

1982 Sculptural Jewelry Exhibition

Doneghy Collection of Southwest Indian Silver

1984 Jewelry International Exhibition

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.