Metalsmith ’95 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

54 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1995 Winter issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Rachelle Thiewes, Eleanor Thomas-Allen, Zack Peabody, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jewelry Symposium

The Oakland California Crafts Museum

Oakland, California

July 16, 1994

by Susan Kingsley

The Oakland Museum, California Crafts Museum (recently re-named the Contemporary Craft Museum) and Susan Cummings Gallery presented a one day Jewelry Symposium on July 16. Held at the Oakland Museum, there was a standing room only crowd of 100 of which only a few, surprisingly, were artists. Following an introduction by Curator of Decorative Arts Kenneth Trapp were the featured speakers: San Diego artist and professor Arline Fisch, San Francisco Bay area art historian and independent writer Charlotte Moser, and independent curator Lloyd Herman. The symposium concluded with a panel moderated by Susan Cummings and Kenneth Trapp with artists: Colette, Marilyn da Silva, Sandra Enterline, and Christina Smith, who each gave a brief slide presentation of their recent work.

The impetus for the event was the concurrence of three significant exhibitions, "Jewels and Gems, Collecting California Jewelry" at the Oakland Museum, "Brilliant Stories: American Narrative Jewelry" at the California Crafts Museum, and "California Jewelers" at the Susan Cummings Gallery. The joint effort of the three entities in organizing this symposium was commendable. As one who has attended many conferences and symposia and listened to numerous lectures and panels about our field, I found of this one full of little surprises and realizations - new ideas, connections, and perspectives. For those in attendance who were less familiar with the field, I suspect the majority of the audience in this case, the symposium and its related exhibitions were an opportunity to be exposed to a wide selection of previously overlooked, undervalued, and largely undocumented artworks.

In his opening remarks, Kenneth Trapp observed that the role of the curator is to be future oriented even when delving into the past. He described the exhibition "Jewels and Gems" as a miracle, because he "was able to convince some of the administration to make a firm commitment to develop a jewelry collection - with money." He pointed out that we should remember that the pieces we see today will not always remain contemporary. "We must collect and protect our history and not leave it to someone else to tell our story." He related that this was brought home poignantly when he curated the "Arts and Crafts Movement in California" exhibition because not one single piece ever appeared that he could identify as having been made by a person in an arts and crafts guild.

Although she found her assignment to speak about the history of jewelry in southern California a "difficult one," Arline Fisch made a lively and visually interesting presentation. She began by stating that her own interests and lifework have been "global" - and that although she had lived in southern California for more than 30 years, her knowledge of the history of the region was scant. Research turned up very little documentation of jewelers and metalsmiths in southern California. The slide library at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles provided the primary support. In one case they had the only existing documentation of an artist's work, and it was only because the artist, now deceased, had donated her slides. Sadly, some images that have "survived" are badly discolored because of the use of RGV film, a motion picture film which was apparently used by many cost conscious southern California artists in the 60's and 70's.

Fisch discussed the work of sculptors who made jewelry, the California Design Exhibitions at the Museum of Pasadena which provided a showcase for the most imaginative work being done, the universities with jewelry programs, the teachers who came from elsewhere, and the graduates who went elsewhere or stayed in California. While the history of the craft before 1950 would have been interesting to hear, her fact filled account of southern California jewelry and metalsmithing from the last decades answered Trapp's entreatment that it is important that we collect and protect the history of our own time.

It was startling to see work that now looked "dated" while remembering how innovative it was fifteen years ago. It raised, anew, questions about the prevalence in California of large scale work and the uninhibited use of materials such as anodized aluminum, titanium, and plastic. Was there some regionally felt impulse to make work that had dramatic presence and used unconventional materials - work that was distinctly different and outside a modernist European aesthetic? Was the East Coast bent on carrying on the traditions of European metalsmithing and jewelry, while the West Coast was reflecting the influence of South American and Asian cultures? Fisch's own work bears a strong connection to ancient jewelry from various cultures around the world. Although there was a great deal of diversity in the Southern California work Fisch presented, one couldn't imagine it having come out of Pennsylvania. She concluded with the observation that in the 1990s she saw a higher level of skill, more technical advancement, and a greater number of metalsmiths earning a living from their craft than when she came to California thirty years ago.

Charlotte Moser brought a very different perspective to her overview of the history of metalsmithing and jewelry in Northern California. An art historian, she is particularly interested in the impact of cultural conditions on regional artistic production. After living in the San Francisco Bay area for more than five years, she was shocked by the realization that there has not been more study of California crafts and their influence on contemporary American art. She wondered how the sense of California as being on the cutting edge in materials and ideas had developed into a 'mystique' about the region, and how the bay area crafts movement, so potent and visible nationally in the 1960s, had come about.

She began by looking at the Arts and Crafts movement in California, and pointed out that like England and the rest of the United States, there was very little jewelry produced. She attributed this to the idea that jewelry and personal adornment had aristocratic associations which contradicted the basic democratic principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Manifestations of the movement in California included architecture such as the mission and shingle styles, designs for homes that merged living space with the landscape and functional objects for the home in clay, fiber, wood, and metal. She pointed out that awareness and appreciation for native and preindustrial cultures, a tenet of the International Arts and Crafts Movement was already in place in California, probably because of its existing native population.

Moser stressed the role of education in the evolution of craft in the Bay Area. The University of California at Berkeley, long considered a world class institution, began teaching craft in 1911, the year women in California got the vote. Textile and metal arts were part of the Home Economics Department and many women studied to be art teachers, still one of the few acceptable career opportunities open to women. In the early 1930s there was an attempt to close it and she related how a strong department head, a woman with a PhD in Anthropology, saved it by renaming it the Department of Decorative Arts. It remained until 1962 when it became the Department of Design. Three faculty members hired to teach in 'design' were among those instrumental in changing the face of craft in California and the country by integrating contemporary art issues into craft media - Ed Rossbach, Marvin Lipofsky, and Peter Volkous.

Moser also discussed the influence of the Bauhaus and a number of individual artists before concluding with slides of a few contemporary Northern California jewelers. It was interesting to think of our geographical region as comprising a "cultural community" that includes craft and metalsmithing. Most of us feel that our practice of craft, jewelry, and metalsmithing has set us apart from artistic dialog in the community and we tend to think of our national, craft and media specific organizations and publications as our 'community' or even extended family. Fisch's career beyond her region could be considered evidence of this propensity.

Lloyd Herman addressed the history of jewelry, from ancient fibulas designed to hold clothing together to amulets that were believed to have the power to protect a wearer, to badges of office and badges of power. He talked about gemstones and how the symbolism of each one was the "story of its power distilled and embodied in abstraction" and related how other cultures hold beliefs that wearing certain jewelry can prevent disease, enhance fertility or prevent the influence of evil forces.

Herman also talked about several jewelry exhibitions that he has curated. "Good as Gold", in 1980, was intended to illustrate the resurgence, among jewelry makers, of interest in materials besides gold, and concepts other than preciousness and status. Also mentioned was "Brilliant Stories", which includes several of the same artists and focuses on narrative work in contemporary American jewelry and provides a selection of works, rich in visual interest and meaning, which Herman categorized as commemorative, myths, folktales, and portraiture. He concluded by saying that "storytelling in jewelry is as diverse as the stories we read in books", and that we need to raise the consciousness of the public in order to make them bestsellers.

The afternoon session concluded with the panel of artists, each of whom showed slides and spoke briefly about their work. Sandra Enterline showed work from her Opposition Series, each piece consisting of two related but opposing pendants coupled by a thin chain, allowing them to be worn on both sides of the body simultaneously. The egg-like forms are quietly organic and loaded with suggested meanings. Although made of precious materials, gold and silver, the subtle richness of the colors, the finely finished surfaces and the minimal forms result in jewelry that transcends any categorization. Christina Smith titles her narrative broaches with captions which summarize an event or situation from her life. She tells her stories, whether sad, profound, or frightening, with great humor and wit, adding another dimension to her beautifully conceived broaches. Marilyn da Silva's most recent work didn't happen to be jewelry. After a devastating house fire, the artist began a series of candlesnuffers: Put Out the Fire. Although one could smile at the symbolism of a snake for the insurance company, a beehive for home and security, a cage for the songbird she lost, the desire to heal and to look forward was present in these functional, unpretentious, and yet profound pieces. Collette, who is among other things, a painter and enamelist, spoke of her jewelry as being from a different perspective. Although she works in precious materials, it is the imagery, her intricate and delicate, rich, mysterious, and sensitive narratives that seduce. One is glad that she decided to be the difficult and rebellious outsider, outlaw, and outcast that she described in her autobiographical introduction.

A discussion followed some provocative questions from the moderators. Susan Cummings, noting that confrontation is a major feature in the work of a number of contemporary jewelers, posed the question "Does jewelry always have to be nice?" Trapp asked the artists: "What qualifies a piece of jewelry as exceptional?" The answers, while not easily summarized, involved stories and anecdotes: lessons learned in years of experience in making, wearing, and observing jewelry being used. The discussion grew to include the audience, and underscored the richness and complexity possible in an artform that interacts with life in such an intimate way. This provided a satisfying conclusion which was not one of closure, but one which encouraged the appreciation of the historical aspects of jewelry in California coupled with an optimistic anticipation of what will come next.

Susan Kingsley is a metalsmith, critic, and writer who resides in Carmel, California. She recently published Hydraulic Die Forming for Jewelers and Metalsmiths.

Brilliant Stories: American Narrative Jewelry

Contemporary Crafts Museum

San Francisco, California

June 4 - July 24, 1994

by Mija Riedel

The eighty pieces of jewelry in "Brilliant Stories: American Narrative Jewelry" are rooted in autobiographical, cultural, and mythical narratives. The twenty-five artists represented draw upon diverse histories and backgrounds, yet there is a personal, intimate inclination which unifies the collection. Curated by Lloyd Herman, Director Emeritus of the Renwick Gallery, "Brilliant Stories" has its roots in earlier exhibitions, including "Good as Gold: Alternative Materials in American Jewelry" and more recently, "Tales and Traditions: Storytelling in Twentieth Century American Art."

The roots of narrative jewelry-making may be traced back through 19th century English mourning jewelry, with its hair lockets and funerary images, to European portrait miniatures and cameo portraits carved in ancient Rome, likenesses which captured the various virtues and vices associated with the person rendered. However, jewelry as social commentary appears to be a relatively new development, with few antecedents besides political buttons. The artists included in "Brilliant Stories" reflect on myths, cultural rites, and life in the last half of the 20th century, and render their ideas accessible on a daily basis by making them wearable.

This is an unusually thoughtful, thought-provoking assembly of work which interacts on multiple levels, invoking numerous, varied analogies among the pieces. The connections and distinctions allow each artist's work to be considered from several perspectives. For example, on a material level, Judy Onofrio's elaborately beaded, collaged brooches correspond to Joyce Scott's beaded neckpieces. Scott's large, beaded faces reference the collar of oxidized sterling faces in Laurie Hall's Protesters, alongside Thomas Mann's deathly silent Endangered Species - Who's Next focusing on animals, extinction, and the changing landscape; connecting again with Onofrio's Mr. Earl, ho noring the arguably extinct American cowboy; which then points to myriad culturally and mythologically inspired works by Carolyn Morris Bach, Jaclyn Davidson, Hollie Ambrose and Wil M. Stubenberg, Eun Mee Chung, Ron Ho, Betsy King and Christina Smith. Each piece provokes interest in another and builds the momentum of the show; the resultant 'whole' is continually evolving, amplifying the sum of its parts.

The pieces interact by means of recurring themes, images, and a wide spectrum of materials. Oxidized sterling predominates, but it is combined with an array of dissimilar materials ranging from Plexiglas, found objects, newsprint, and cow bone to 18k gold, opals, and rubies. The majority of pieces are brooches, a number of which lodge in small shrines or stage settings when not being worn. There is no preponderance of archetypal symbols, but letters, boats, keys, and watch faces surface repeatedly.

Contemporary, culturally-inspired themes predominate. Mythological narratives are rivaled by the search for personal and cultural identity, journeys and rites of passage, the environment, existential and urban angst, coffee, childhood, Mom, and the passing of time. Judy Onofrio and Laurie Hall focus on Americana - Abe Lincoln, wide open spaces, and demonstrators respectively. Hall and Thomas Mann report on the pros and cons of caffeine culture. Mann laments vanishing elephants; Barbara Walter puts one in the circus in her Three Ring Circus with Ringmaster Ring, commenting, "For me, the acts with people were just to fill time; the animals were the stars." Jaclyn Davidson's pieces, incorporating animal protagonists as frequently as humans, are inspired by legends from around the world. Bruce Metcalf's A Flower in the Wasteland is a hilarious indictment of the insular academic world. Robin Kranitzky's and Kim Overstreet's beautifully constructed, haunting brooches relay poetic fragments of unconventional stories, as alluring in what they reveal as in what they suggest.

Ron Ho's eloquent, minimal, oxidized sterling necklaces unite the diversity of his life experiences - traditional Chinese ancestry, a multi-cultural childhood in Hawaii and art school in Seattle - through variations on the chair. Long noodles - representing long life - hang from a pair of chopsticks to a full plate resting on the chair seat below, commemorating the celebratory meal served for a Chinese child's First Birthday. A tea pot and two cups in Yum Cha refer to the highest form of hospitality a Chinese host may offer his guests. In Vanished Wishes, a jacket fixed with a small pink enamel triangle hangs casually from the back rest of the only chair in this group with a vacant seat. The piece is a memorial to all the "wonderful, creative individuals who have lost their lives in the AIDS epidemic."

Eun Mee Chung's work is the least representational and among the most poetic work exhibited. All of her pieces focus on Woman, frequently represented by traditional Korean symbols such as a rose or bird, facing an unfamiliar but necessary journey. David Williamson's Mother's Day brooch was made the year his mother died - "the first Mother's Day in memory that I had not made a present for my mother." Clean Up Week, incorporating a bright yellow and blue antique button with a bonneted woman in long skirts chasing off dirt with a stick, is topped with the child-like sterling silhouette of a house and anchored with a tiny sterling sheet of loose leaf paper listing chores to be done. Roberta Williamson writes about her love for her daughter on silver leaf brooches while Alan Burton Thompson celebrates "…the strengths of women in the varied roles as mothers, lovers, leaders, and individuals" in Genevieve's Decision, made with a cameo, a compass, wood, silver, gold leaf, and a nail.

Harold O'Connor's 'timeless timepieces' are funny, provocative glimpses at our conceptions of time - how we have organized it and how it, in turn, organizes us. Figures of speech help to illustrate his ideas. O'Connor's Serving Time refers verbally to jailed convicts, but visually we are served a tiny sushi tray and miniature chopsticks on a table - all fabricated from precious materials. Timeless Watch: Conference Time is an 18 karat 'wristwatch' in which the numbers have been replaced with mini businesspersons seated at a round table, folios and drinks at hand; with no hour or second hands present to advance the meeting, it seems not only timeless but endless. Timeless Watch: Neighborhood Watch opens up to reveal two houses side by side, their occupants keeping a watchful eye on their property and each other. Kiff Slemmons's four hand brooches reflect Time's passing through the changing of the seasons. In Winter: Cracked Ice made from an enameled watch face and acrylic frosted to resemble ice, she captures the stalled, frozen character Time takes on when the days are short and the outdoors forbidding.

On a minor but significant note, the exhibit is beautifully designed. Originally intended for a foreign audience, there are brief, informal biographies about each artist as well as notes on each piece of jewelry, allowing the audience to compare not only materials, techniques, and visual content but reasons for making art jewelry, senses of humor, and purposes.

"Brilliant Stories" included the work of: Stephen J. Albair, Hollie Ambrose, Wil Stubenberg, Carolyn Morris Bach, Eun Mee Chung, Jaclyn Davidson, Susan Ford, Laurie Hall, Ron Ho, Betsy King, Robin Kranitzky and Kim Overstreet, Thomas Mann, Bruce Metcalf Harold O'Connor, Judy Onofrio, Joyce J. Scott, Rhonda Shikanai, Kiff Slemmons, Christina Y. Smith, Alan Burton Thompson, Barbara Walter, David Williamson, Roberta Williamson, and J. Fred Woell

Sponsored by the United States Information Agency to correspond to the Year of American Craft, "Brilliant Stories" was designed specifically for the Mideast, the collection presenting an alternative to the long tradition of jewelry - particularly elaborate gold work - which flourishes in that region. The exhibit toured for one and a half years in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Pakistan, Egypt and Morocco - where one member of the audience felt compelled to comment in the guest book, "this is not real jewelry, it's only art".

"Brilliant Stories" is now touring the US. under the auspices of the International Sculpture Center. The 1995 itinerary includes the Headley/Whitney Museum in Lexington, KY, February 5 - March 19, with additional venues to be scheduled. For further information contact Tom Yarker at the I.S.C., Washington DC., (202) 785-1144.

Mija Riedel is a writer and metalsmith who lives in San Francisco.

Brooch - The Subject

Tempe Arts Center'

Tempe, Arizona

May 20 - July 31, 1994

by Kristin Beeler

Every exhibition establishes its own community. Based on a common theme, a collection of works presents a cross-section of a specific time in the development of form or media. The community of 82 pieces from 55 artists which comprise "Brooch: The Subject" have in common the basic pin form. These are the modern heirs to the ancient fibula. In their selection, jurors David Pimentel and John Hayes sought originality variety and a level of commitment to craftsmanship. With an emphasis on variety sufficient room was made to include new and unexpected pieces among the comfort of well-established and familiar names. Content and subject matter were not an issue since primary importance was placed on the diversity of approaches to the form and function of a brooch. Furthermore, because there were no limitations on media, the overall palette of the exhibition was significantly broadened by the introduction of fiber, ceramics, paper, plastic, and paint. Indeed, with so few restrictions on entries, it is surprising that "Brooch - The Subject" did not reveal a more varied community.

The exhibition sports many pieces which fit neatly into common genres of jewelry styles, though others excel in terms of technique, content, imaginative use of materials, or simply cleverness. Keith Belles's Optical Illusion face pin, for example, is made of recycled materials and has baby doll eyes that close when the piece is placed horizontal. Like Renee Harris's colorful embroidered pins, Design and Coffee, the work is basically just good, clean fun.

At least one quarter of the show is given over to unpretentious, well-designed pieces whose first goal is to be interesting or beautiful, yet serviceable objects. Carol Webb's Banana Pins are terrific fold-formed pins with patterns etched into laminated copper and silver. The marquis-shaped pod form isn't particularly new but Webb has managed to put several of the classic metals workshop techniques to excellent use. Several objects reached out beyond good design into the realm of some obscure narratives. Theresa Levering-Brown's Haven of Entrapment hints at something other than its sweeping texture across a simple, triangular silver shield form. One piece that is impossible to forget is Robin Kraft's enigmatic Flaw in which a tiny bird's nest becomes the lens of a fabricated jeweler's loupe. Although these pieces are a little too obtuse to decode entirely, their combination of mystery and meticulousness makes it difficult to let go of their images.

Among the seven recipients of juror's awards were Deborah Lozier and Sarah Perkins, enamelists with extremely different approaches. Lozier's Cocoon Series of three pod-shaped, torch-fired enamel forms are rough, raw and practically uncivilized. But the burnt patterns of rust and ocher maintain the soft logic of natural forms and keep the pieces from becoming too out of control. Alternatively, Sarah Perkins's enameled Tumer Brooch is an exercise in restraint. The creamy white egg-like form has subtle, opaque, pale, yellows and blues with a few lines of copper. For those who can enjoy a sort of Abstract Expressionism, it is eye candy. The flawless, liquid control of color across the surface is something we recognize in the same way we recognize our own emotions and thoughts. It creates tangible forms for tacit realities. A second Perkins piece was far less successful. A combination of blocks of solid opaque color with roller-printed gold and silver, Light Patch Brooch, lacks most of the grace and intelligence of the artist's usual work. Whether a new direction or a temporary tangent, the piece has an anonymity that is uncharacteristic for her.

Honorable mention in the enamels category, had there been one, would surely have gone to Cecelia Anne O'Kelley for Thanksgiving Day Fireworks at Lake Guntersville. The combination of transparent blue-gray enamel over forged silver makes a strikingly beautiful piece. O'Kelley has both the gift for creating vivid dreamscapes and the technical ability to seamlessly integrate the enamels with their mounting.

Another award was given to Daniel Jocz for his Sketch Book Series -Tocoma, Italy. Jocz, typically known for his semi-cybernetic jewelry, surprises his audience with two inspired little brooches that are made of acrylic paint directly on sterling. The metal is treated like heavy paper with shapes inside the painted landscape outlined by piercing and bending. The effect is one of absolute immediacy. Although metal has certainly been painted before, this particular union has a freshness that helps it evolve beyond the vanilla imagery of a landscape. The obvious question that arises is: "why use silver?" Is the preciousness of the material supposed to relate to the images painted on it? If so, how? If not, why use sterling? Or can it be that, as in Pre-Hispanic cultures of Central and South America, it is sufficient to know that there is precious metal underneath the paint without seeing it?

Others receiving Juror's Awards were Amy Linn and Jewell Clark. Linn's quizzical little brooch Second Guess is handsomely constructed with doors, latches, and pulleys. It has the appeal of an eccentric toy needing to be played with to be fully appreciated. Clark's List Series pins are four refrigerator-magnet sized notes which, for example, remind the viewer to: "break off affair - seek fulfillment - vacuum". Another reminds us that we need, " veggies - cheese - integrity - cat food - love - deodorant". The handwritten notes etched into silver are a smirking record of the same modern priorities that tell us to save the whales, be young, have fun, drink Pepsi. Like the transitory values to which they testify, the pieces are superficial one-liners. But good one-liners.

Two more awards went to Michael Croft and R. Jackson. Both artists use steel scraps and employ gold only for design accentuation and in findings. Croft's Scraps brooches, one of Damascus steel and granite polycast, the other Damascus with a stripe of transparent red acrylic, emanate a cool aloofness. The materials are bound into a tight formal arrangement with pristine craftsmanship that doesn't leave behind human marks. On the other hand, R. Jackson's three pieces Implement, Radio Telluric, and Summer Night have a slightly tortured, weather-roughened warmth. Sapphires, garnets, and tourmalines are added to the junk steel scrap but rust is kept for its expressive qualities and the implication of some unknown history.

While most of the pieces in the show are of a traditional, wearable scale there are those that, with more or less success, address the issues of wearability. For example, Vernon Thiess's linear construction City Whirl, standing 15″ tall, pushes the envelope to its tearing point. It is a fully three-dimensional diorama with a pin finding. To those who prefer slick, tidy craftsmanship, the piece has a neo-trampled look. If Eleanor Moty's work (also included in the exhibition) is uptown, then Thiess's work is inner-city. It's kernel grows from an attempt to capture the transient experience of life rather than from conforming to the solidity of 'proper' scale and craft. Taken to extremes, it might simply turn the body into a walking sculpture stand.

Similarly, David Griffin's pieces Other Grass Rubberneckers and Which Way the Wind is Blowing are nicely constructed brooches approximately 10″ long hung on 12″ bronze plaques. Like Thiess's piece, Griffin's works are fairly large, linear narratives in silver. However, Griffin divides the action of the 'story' into sections down the length of the brooch instead of having it take place in the round. Although they refuse to be mere accessories, the pieces seem like they could be worn without losing parts of the narrative.

There are probably as many ideas about what is essential to a brooch as there are people making brooches. While some are obsessed with constructing the perfect finding, others are interested primarily in surface treatment, and others still are conducting experiments in form. The object presents a different challenge to everyone who attempts it, dependent on the individual's personal program. "Brooch - The Subject" attempts to represent as many of these agendas as possible and while some connections to the central theme may sometimes seem looser than others, they all remain a part of the same community raising its own distinctive set of questions.

Kristin Beeler is a metalsmith living in Tucson, Arizona.

Rachelle Thiewes's New Work

Jewelers' Werk Galerie

Washington, DC.

October 9 - October 29, 1994

by Elizabeth Jones

Any exhibition of Rachelle Thiewes's jewelry fails to present one quarter of the work at all because besides the dominant silver and the accents of slate and gold, for this artist the most critical physical element in her work is the human body. Thiewes's pieces do not arbitrarily decorate the body like traditional jewelry which hangs, encircles, or perches upon the wearer as sculpture on a pedestal or pictures on a wall. Sometimes her work creates a geometric counterpoint to the organic curves of the body, restricting movement and demanding attentive manipulation. At other times, as in this show, the pieces correspond to the body's shapes and rhythms. The wearer achieves both an awareness of the artwork and a consciousness of their own body. "Society is moving so fast, we don't pay much attention to ourselves", Thiewes says. Her work demands that you slow down and pay attention. Above all, she doesn't want her jewelry to be passively worn, to be forgotten, nor does she want the wearer to forget herself. Thiewes's objects reflect the same enlightening objectives of performance art. According to Allan Kaprow: "The purpose of lifelike art [is] therapeutic: to reintegrate the piecemeal reality we take for granted. Not just intellectually, but directly, as experience… Of all the integrating roles lifelike art can play… there is none so crucial to our survival as the one which serves self-knowledge. You can't 'talk back' to and thus change an art-like artwork but 'conversation' is the very means of lifelike art, which is always changing" (Artforum, December 1983, pp.37-43). Thiewes's artworks are in constant conversation with the wearer and with the world.

The most successful pieces in the exhibition were seven necklaces entitled Reflections of St. Mary's. Hanging on long thin chains and pointedly positioned at pubic level, a heavy, silver circle supports a variety of shapes in a seemingly random order. The circle, disk, quill, and an occasional doubled cone shape form the basic vocabulary which the artist manipulates by changing scale, texture, relative position, and reflective surface. The intimate size of the Jewelers' Werk space magnified these pieces, something a larger space is often unable to do. A life size photograph of a model provided a dramatic field for displaying a single brooch.

The necklaces, when worn, rhythmically pendulate between the pelvic bones, when the wearer walks. The freely moving elements recall the gentle sound of a breeze playing a wind chime. The repetitive intersection of the body and the artwork serves as a constant reminder of the body's motion. The sound may even encourage the wearer to silence the piece, leading to a new discovery of the tactile pleasure inherent in the forms. The inspiration for these pieces derives from Thiewes's childhood memories of nuns who wore their rosaries from their belts. These rosaries swayed and punctuated the sisters movements as the crucifixes fell against their ankles. The peripubic placement of these necklaces, however, points to a sexual allusion more beholding to the bejeweled tummies of belly dancers.

Four necklaces signal a new direction for Thiewes, away from sound and visual confrontation and toward silence and near invisibility. These almost ephemeral objects explore line and space through a long, thin chain, sparsely accented by the familiar, but now smaller, elements. By freeing the chain of heavier elements, Thiewes allows the line to take the shape of the wearer as it falls along the curving contours of the body. Although the intention here is good, the work still seems unresolved because the line overwhelmingly dominates the elements, leading to a kind of visual boredom. Also, because of its lightness the chain fails to adhere significantly to the curves of the body. Yet despite these difficulties, the serenity of these pieces may prove attractive for many wearers.

Three bracelets complete the exhibit. Each is constructed from a pleasingly weighed silver circle, which moves freely up and down the forearm. Subtle spikes alternate with fringe-like quills marrying the unlikely images of elegant charm bracelets and aggressive pit bull collars. In a world too much concerned with the visibility of the body, the artwork of Rachelle Thiewes brings us back to the body's most funda-mental, indeed, most primeval sense - the sense of touch. It also puts us in touch with ourselves and with our world.

Elizabeth Jones is an art historian and critic who teaches at the University of Texas, El Paso.

Eleanor Thomas-Allen: Contemporary Artifacts

Andrea Kennington: Family Portraits

Community Council for the Arts,

Kinston, North Carolina

April 18 - May 15, 1994

by Biruta Erdmann

Placed together in the same exhibition space, the works of Eleanor Thomas-Allen and Andrea Kennington offer a wealth of cultural and personal information. Thomas-Allen's and Kennington's design of the installation - housing, placement, and spacing of the objects - made an effective use of the architectural space that created a compelling visual whole of ceremonial dimensions.

Thomas-Allen is an established jeweler, but her latest works (ten pieces) show a different agenda concerning the wearable object. While some of the pieces in the exhibition, such as the purse and the bracelets reveal the functional intent and artistic precedents readily, the "Contemporary Artifacts" display a marvelous sense of formal, functional and intellectual ambiguity. Contemplation of Fun is a beautifully crafted object of uncertain mythic/historic origins. Here the artist refashioned the concept of a mass-produced clacker toy into an elegant pendant/toy, which may fulfill more than one functional requirement. Thomas-Allen's penchant for the curvilinear forms associated with Art Nouveau characterizes this piece and several others in the exhibition. She successfully distills and recombines lines of the plastic toy into a shape that is as much Art Nouveau as it is postmodern, or revisionist Pop.

Wayne's Shaving Brush might be understood as another update of a mass-produced, though now obsolete object. By using fiber optic cables for the brush and L.E.D. lights as gems within the handle of the brush, Thomas-Allen creates a futuristic looking object. The handle of the brush is decorated with etched and copper plated mathematical signs. The brush symbolically represents her husband, and the Contemplation of Fun functions as a metaphor for her son.

Unearthed Neckpiece, of clay and copper, is the largest and the most sculptural work in the exhibition. This shield-like, wall-mounted clay form, with its crusty surface and weathered edges, recalls archeological finds of ancient, magical charm. The title of the work suggests an object from the past, the form however, remains ambiguous. This imaginatively invented artifact explains the artist's thinking about artistic precedents, a sense of time, and historical identity. Perhaps, the artist does not wish to permit the viewer to discern the epoch or culture in which the maker or a wearer of the neckpiece lived.

For Kennington, whose artistic training is in the fiber arts, this was the first major exhibition of her achievement in metals. "I generally use collage type method in my metal work", said Kennington. The artist used the form of the medal in the creation of these nine brooch/portraits. Although, not visible from the front, the brooches have a mechanistic construction. Each brooch consists of three moveable and wearable sections. The end section of the brooch can be worn as a pendant. The wall mounted, wooden boxes in which each brooch is placed, are perfectly suited to hold the family treasures. Though rather austere in design, the boxes contribute to the heraldic effect of the whole. These portraits reconnect Kennington with her roots and memories of relationships deepened over a lifetime.

For Ma Mere, Kennington used the bee and a beehive motif to symbolically represent her grandmother as the head of "the family tree". This three-part brooch is a superb example of Kennington's handling of fabrication, casting, etching, and layering. An inlay of a reduced color Xerox of an old photograph completes this emblematic design. The hand-colored Xerox photos of the female images invoke an illusory sense of time - the Xerox photos of the men resemble tin-type likenesses. These portraits have roots reaching back to the nineteenth-century designs of birth and baptismal certificates and family records in the folk art of America.

Kennington's versatility and her background in fiber arts is demonstrated in her use of embroidery, beadwork, and fabric transfer. An embroidered centerpiece, featuring a bird in a landscape, forms a part in the design of her sister's portrait. An arrow-shaped beadwork ribbon connects the top and bottom section of her brother's portrait, establishing a symbolic tie of the richly ornamented surfaces with American Indian motifs. The Traveler is for Kennington's mother. Fabric transfer is used to create the map-shaped ribbon and references to travel, such as an automobile, an airplane and maps, play an important part in the characterization of the person and the relationships which the artist honors.

Self-Portrait concludes the series. Fish surround and frame the girl who seems to be looking back to her grandparents, parents, and siblings with a loving gaze. The use of the fish motif poetically expresses the artist's philosophical musings about her roots and aspirations. Kennington invites the viewer to share her personal experiences.

Biruta Erdmann is an Associate Professor Emeritus at the School of Art, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina.

The Contemporary Silversmith

American Silver Museum,

Meriden, Connecticut

July 10 - Sept 9, 1994

by Bernard Bernstein

This exhibition, consisting of 32 works by members of the Society of American Silversmiths (S.A.S.) inaugurated the opening of the American Silver Museum.

The museum, housed in a tastefully-restored historic building, is in the center of Meriden. When fully operational the museum will have three floors, totaling about 15,000 square feet. It currently has a gift and book shop, a theater, educational activity center, video-viewing room, and space for temporary and permanent exhibits. Still in development are areas for craft demonstrations and workshops, a library/research center, and a growing collection of tools, silver objects, and archival materials relating to every aspect of silver.

Why Meriden? For over a century beginning in the 1800s and extending into the 1900s it was known as the "silver city". Meriden, Wallingford, and other local towns were at the heart of a region involved with the production of pewter, sterling, and silver-plated ware.

As for the museum's decision to showcase the work of the S.A.S., I can not think of a more appropriate choice. This organization, founded by Jeffrey Herman and based in Providence, has about 70 artisan members. The focus of their metalsmithing activities is directed at hollowware, flatware, sculpture, and what I will call "metaphorically functional" objects. Work submitted for all S.A.S. sponsored exhibitions must be at least 50% silver. So, the link between the museum's historical base and its mission and the activities and philosophy of S.A.S. is a strong and symbiotic one.

The educational background of the members of S.A.S. appears to be quite diverse. Most of the contributors are from the academic world, either teachers or past and present students. Some may have received training in non-university settings such as craft centers or workshops, and some may be self-taught.

In general the orientation is in a different direction compared to the "art" objects often pictured in the articles and gallery ads in magazines like Metalsmith and American Craft. The objects in this show are mostly functional, with careful attention paid to traditional design concepts. Technical mastery is given a high priority. Many of the objects would be appealing to the sophisticated collector including pieces that fall into the category of sculpture. I'm thinking of Ronald Wyanko's sinuous spiculum-styled Ramous, Cynthia Eid's Animal Anomaly and Susan Ewing's meticulously-executed vessels, Inner Circle Teapot 2 and Penetrated Sphere.

The exhibition is a cross-section of stylistic influences stretching from today to the distant past; elegant Scandinavian or modernist forms predominate. Some that stand out are Ronald Pearson's forged candleholders, Chunghi Choo's minimalist one-piece folded cakeserver, Jack da Silva's ladle, John Cogswell's and Fred Fenster's Kiddush cups, Jeffrey Herman's Petit Fours server with two strategically placed sapphire accents, Fred Miller's silver and ebony bowl, Harold Schremmer's standing cup, and Robert Oppecker's large tureen, whose execution follows his personal approach of assembling raised and cut-up units in different configurations to produce surprising intersections of edges and surfaces.

The post-modern, possibly Memphis-related look was represented by Thomas Muir's wire and sheet liquor cups, Boris Bally's Cero Top bottle-cork made up of silver, brass, ceramic and cork, his Paved Spoon 4, made of sterling and concrete; and Pauline Warg's finely-crafted tea strainer and drip cup. I am, however, having trouble understanding why Bally would make a serving spoon with a massive concrete and silver handle terminated by a disproportionately small bowl.

Pre-modernist influences were reflected in Harold Rogovin's immense oval punch bowl and ladle, and Henry Petzal's Bowl # 94, featuring a line of shallow bosses with incised borders running around the circumference.

I'm not sure whether this is a phenomenon that is more pronounced in jewelry than in hollowware, or that the pendulum has begun to swing away from content-loaded objects that tell stories or make statements, but I noticed very few examples of the narrative approach. Four objects of this type attracted my attention and represent what I will call an attempt to integrate form, function, and content. Olle Johanson, who seems inclined toward small, simple bowl-forms exhibited one which had a V-shaped section cut out of its side, starting at the rim, which made the piece look as if it was splitting apart. Inside, resting on the bottom, was a copper representation of a broken hammer and sickle. The tide, New Era, helped to end any doubts about the symbolism, though its use exacted the price of undermining function.

More functional and more complex was a candle-snuffer by Marilyn da Silva, entitled Put Out The Fire. It is a wheeled cart with a long tree-branch-shaped and textured handle. A crouching rabbit in the cart looks longingly at a carrot at the far end of the handle. Is the content arbitrary or is there some conceptual connection between the "carrot on a stick" theme and the act of candle-snuffing?

I am also including Sue Amendolara's Cascading Foliage scent bottle in this category. This is a sensuous and complex construction of concave and convex surfaces suggesting a female figure faced with applied, leaf-shaped units.

Ronald Wyancko's pill box, in particular commanded much of my interest and admiration. It is a utilitarian, straightforward, fat, rectangular box with a hinged lid covering 28 hemispherical compartments which hold, I would guess, a weeks worth of pills to be taken four times a day. Much of the artistry, artisanry, content, and spiritual significance are contained in the design of the lid. Most of the space is occupied by a rectangular frame with an intricately sawn border, surrounding eight differently-proportioned rectangular plaques. Each plaque is an image in relief of some object or situation that probably has personal meaning for the person taking the pills. For instance, there is a ping-pong table, two figures on opposite sides of a bed under a blanket, an antique car parked in front of a house, and other images as well.

Compare this to the plastic medication-organizers available in drug-stores. What Wyancko has made is similar to Cogswell's and Fenster's Kiddush cups. The religious ritual of reciting a blessing and drinking wine at the beginning of the Sabbath can just as easily be done with a plastic cup, but the Psalmist wrote: "Worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness", which encourages us to enhance the performance of a ritual with special meaning through the use of a beautiful, precious ritual object. Having to take medication several times a day every day is an important quality-of-life ritual and Wyancko has elevated that ritual from what might be an annoying inconvenience to a semi-sacred level by creating a beautiful ritual object in precious metal, that contains personally meaningful iconography. This object successfully integrates form, content, function, materials, and skill.

The American Silver Museum and S.A.S. have collaborated to celebrate the museum's birth with a fine exhibition. I look forward to the many that are sure to follow.

Bernard Bernstein is a writer living in Bronx, New York

Zack Peabody: The Structures of Denial

Jewelers' Werk Galerie

Washington, DC.

June 16 - July 7, 1994

by Claire Dinsmore

Since the advent of the machine age in the eighteenth century, the idea that either philosophy or technology hold sway in realms of human endeavor is one which has been posited countless times. Yet is not the impetus for both the same? In Martin Heidegger's essay The Question Concerning Technology the realms of philosophy and technology are brought together in the form of the one in deep contemplation of the other. The link forging itself between the two is the way in which they are both explored: that way being questioning, thinking, ruminating. This way is the 'essence' inspiring technology, and its manifestations is a flexing of the muscles of human prowess.

In Zack Peabody's first solo exhibition of jewelry and small sculpture on view at Jewelers' Werk Galerie in Washington, DC., these extremities are explored with almost intimidating intensity. The works themselves utilize the elements of a visual language that appear well versed in the constructs of engineering and mechanics. The pieces are constructed of, literally, hundreds of small parts that either boggle the mind via their complexity, or tire it with their seemingly infinite repetition. The application of the will to mastery is evinced here with rather astounding concentration on what appear to be tiny machines, and therein lies the contradiction: what is the function?

Mechanics imply kinetic workings, motion, doing. In Peabody's works the state is that of extreme stasis, iterated by their definite solidity. This negates the factor of use that is generally a given in machines. One could suppose that these works are simply manifestations of Peabody's aesthetic, or argue that wearability is a use. However, it is clear such simplicity of mind did not create these small technical wonders; these works are out to prove something.

The wearability factor is obviously unimportant to Peabody. He makes this fact quite clear by not mentioning it, or the concept of the body as portable gallery, even once in his 'Artist's Statement" (an integral part of the show I believe). Peabody himself denies that these works are the visual manifestations of a philosophy (or at least the concept of philosophy swathed in the notion of the abstract which is, of course, the antithesis of the exactitude and order which informs this work). Nevertheless, these pieces are not about jewelry, or about the body, nor are they the purveyors of an aesthetic. They are about their inner meaning. Heidegger would say that they are ways of 'revealing', sensuous forms carrying a message about human ability: our ability to create, to understand, and to order to think, and to rationalize. These are forms with which to evince the glory, as it were, of human cognition and the triumph of human control in the midst of nature's chaos, structures in direct opposition to the power of the elements. They are the embodiments of a form of weaponry, that weapon being denial.

"Like radio towers rising against the countryside, they defy the natural, the random." Peabody's statement sets the tone. His use of corrosion resistant materials to deft the erosive natures of time's passage is "…an attempt at immortality…", as if fixing the impress of his existence, his small slice of time, with a voice strong and resonant enough to withstand time's heedless ravages.

Yet machines fall into disuse as they are superseded by humankind's ever increasing knowledge and ability. Although the drive in technology is one of the will to power ultimate control over the elusive Forces of nature and the sustenance of the species, it has no concern with the individual.

All English words formed around the base of tech (such as "technology") stem from the Greek root teks meaning "art". It seems the spirit of etymology played the divine role of muse here. By bringing the language of technology into the realm of art Peabody shifts the focus from one that, although bearing humankind's unmistakable imprint, avoids the individual via the anonymity engendered by sheer mass. He then humanizes that language even further by bringing the work into the small and intimate realm of jewelry.

Upon an initial viewing it would appear, perforce, that this work is not expressive. The impulse which inspired it is the same as that which drives many machinists, architects, metalsmiths, mechanics, engineers, etceteras (they are often referred to as "tech-heads"). The drive is not that which is found to be the chief inspiration (as Kant would say) of many an artist: the longing towards the sublime, but instead the needs of the human ego. Peabody's work expresses such needs sincerely, and what better way to voice them than through the (seemingly) invincible material of metal?

Claire Dinsmore is a writer who lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

Kris Patzlaff: New Work

Mobilia Gallery

Cambridge, Massachusetts

June 4 - July 30, 1994

by Jan Baum

Meticulously crafted and poised, the work of Kris Patzlaff beckons and entices its viewers. This jewelry, composed of thin intaglio panels of oxidized sterling silver with details of semi-precious stones and high karat gold, is earnest in approach.

The various patterns on the framed intaglio panels allude to hieroglyphic writing, they seem to want to tell us something. Each panel is dense with patterns reminiscent of maps, aerial views of cities, city plans, circuit boards, and conglomerations of directional symbols and doodles. A few of these patterns also recall contemporary graffiti artists such as Keith Haring, though Haring's marks are representational while Patzlaff's are non-representational, linear, and more ambiguous.

The jewelry balances on delicate lines. It is sober in its limited color scheme, the arrow-like protrusions which seem to protect the wearer, and the solidity of its appearance. At the same time, the work is playful and inviting with its dangling adornments and the doodle-like quality of some of the patterns, even the edges of the arrow forms are rounded and non threatening. Each element and panel is connected with a hinge which allows for movement, which is always smooth and elegant and in concert with the body. The weight and size of all the work is just right, neither too light nor too heavy to be worn, physically present though never encumbering. The work falls within the historical traditions of jewelry.

The most prevalent feature of Patzlaff's pieces is earnestness, arrived at through the artist's sensibilities and aesthetic. A great deal of information is communicated formally. The seriousness and sobriety of the work comes through the limited color scheme, oxidized silver and gold detail, the solidity of the consecutive panels, and the meticulous craftsmanship. The work has life beyond this sobriety with fecks of color and the enticing, dangling ornaments. A sense of purpose comes through its functional wearability, its patterns which seem to bear information, and the attention to details such as the intaglio printed rivet heads. This attention to detail says this work is important enough to take care of all of the finest points of ideas, intent, and construction.

The shapes of the individual panels do not seem to point to any specific significance, though the combination of these slightly curved, tightly joined panels create a solidity that seems shield-like and protective (especially considering the arrow-like elements). Central panels, dangling elements, and rivet details, are all framed and the pattern is raised suggesting plaque-like associations and acting as a further signal that there is information or something of significance here, however, what that information is remains provocatively unclear.

The work is intentionally ambiguous. It is made in response to the artist's questions and personal inquiries. In a statement, Patzlaff says she wants her work to address the "mysteries of humankind" and that she "strives for the same ability 'primitive cultures' have…to touch a part of us we are all trying to understand." Some unanswered questions remain, however. Which mysteries of humankind is the artist addressing? Are there more specific ways of addressing individual "mysteries" that may produce more meaningful work? Which part is the "part of us that we are all trying to understand." Is turning to 'primitive culture' as a means of addressing these issues appropriate?

This work is not confrontational or statement-oriented. Rather it is rather quiet and waits to be discovered and upon discovery, it is intriguing, impressive, and seductive. And even considering my questions and challenges, I still wanted to wear this jewelry. And isn't that the sign of no small success?

Jan Baum is a metalsmith who has recently moved to Portland, Oregon.

Contemporary Metalsmithing: Behind & Beyond the Bench

The Gallery at Craft Alliance

St. Louis, Missouri

June 10 - July 23, 1994

by Noel Leicht

This rich sampling of work from the current American metalsmithing community demonstrated a dynamic breadth of creativity, diversity, and craftsmanship. The 25 artists invited by Curator Joe Muench to participate in "Contemporary Metalsmithing: Behind & Beyond the Bench" expressed themselves in myriad ways: holloware, jewelry, swords and knives, functional utensils, sculpture, narrative wall hangings, even toys. Their willingness to explore new techniques and to experiment with changing styles was a poignant statement of the artistry that has enriched metalsmithing in the last three decades.

Muench planned this exhibition from the perspective of a metalsmith and an educator. He wanted his students at Craft Alliance as well as the community-at-large to understand what happens technically and intellectually during the creative process. He shunned vague artist statements and critiques and asked the participants to directly address their goals, inspirations, influences, styles of expression, technique, artistic development, and aspirations. He requested works about which the artists were most passionate and/or pieces that they considered 'landmarks' in their technical or artistic development.

Viewers were privileged to see many older works still in the artists' possession that are usually only seen in metalsmithing publications, among these 'landmark works' were: Betty Helen Longhi's 1960 Ladle for a Left Handed Lady; Brent Kington's 1965 fantasy toy, Air Machine; Mary Lee Hut intricately woven 1973 bird-like, Neckpiece #9; Jon Havener's 1973 Stretched Asymmetrical Bowl; Bill Fiorini's 1974 Figurative Hair Comb; Chunghi Choo's 1982 electroplated Peace Lily; Richard Mawdsley's masterpiece of fabricated tubes, Medusa; and Joe Wood's 1986 Black Halex Neckpiece; of ping pong balls; among others.

Muench's premise and execution were thoughtful and well planned. The landmark pieces from the sixties and seventies were juxtaposed with current work by the artists. Mounted on neutral linen backgrounds in simple museum vitrines and wall cases, the works were displayed with a variety of collaborative materials: original working sketches, work-in-progress photographs, artists' remarks, personal memorabilia, and several (tasteful) promotional pieces.

Interspersed throughout the exhibit were also photos of the artists, a glossary of metalworking terms and, for viewers unfamiliar with metalwork, poster-sized photographs depicting common metalsmithing techniques; not too much detail - just enough collateral texture and color to enlighten and satisfy a viewer's curiosity.

Individual booklets which contained commentary, pertinent background information, and review information from the artists about their careers and the exhibited work offered visitors provocative and virtually direct personal dialogue with the artists. The cover of each booklet featured a photo-copied hand of the artist, which for Muench defined the artist since "…the hand is a major tool of the metalsmith."

When the works of the 25 artists were studied as a whole, it was evident that an enormously influential and fruitful network exists within this artistic community. Subtle influences and interactions on many levels have created a visual glossary of styles and techniques - interacting, converging, synthesizing, and diverging - that result in a fascinating progression of process and expression.

The sleek, pristine lines of Scandinavian design of the fifties and sixties seen in works by Heikki Seppä and John Marshall are echoedin Betty Helen Longhi's vessels and Chungi Choo's electroformed shapes, but with different nuances and aesthetic goals.

Mokame gane is seen in Chuck Evans's early jewelry and also in John Marshall's current abstract hollowware form; Philip Baldwin and Bill Fiorini use a similar process in their blade making. Brent Kington pushed traditional black-smithing techniques to create sculptural forms; his influence is seen in the sculptural forgings of Rick Smith and Jon Havener.

Experimentations with colored and patinaed finishes were prevalent in the exhibition. Helen Shirk introduced subtle surface color to her spun and hammered copper bowl with prisma color pencils. Chungi Choo featured a riot of brilliant hues in her anodized aluminum brooches. Betty Helen Longhi incorporated reflective color in her seductive niobium and silver vessel form. Responding to the colors and textures of western landscapes, Timothy Lloyd incorporated soft luminous color in his small sensuous brooches, while Billie Jean Thiede experimented with surface treatment and patina on her formed copper teapot.

Boris Bally's recycled 'decayed' found objects push the limits of his jewelry and sculpture. David LaPlantz's work found inspiration in decoration, politics, and current events. Besides investigating surface treatments, color, and patination, Joe Wood indicated his interest in metal pieces as significant cultural objects. Lucinda Brogden narrated incidents of her life in traditional repousséd bronze wall plaques.

Several metalsmiths reflected on history for inspiration. Thomas Muir worked figurative shapes into a tazza, a historical metal form. Jim Malenda exhibited his first experiment with free standing Stations of the Cross. Bill Fiorini referenced Japanese, Native American, and European designs for his patterned mosaic damascus knives.

Concern for form continued to be a main focus: Susan Hamlet's jewelry illustrated her ongoing evolution from industrial to figurative forms. In a two-dimensional photographic display, Rachelle Thiewes demonstrated how her sculptural jewelry designs relate to body form and motion. Several Daniel Jocz rings explored traditional adornment as sculptural forms. Brigid O'Hanrahan's vessels highlighted fabricated forms of mysterious double wall construction. Chuck Evans's tipped sake server played with his present interest in the off balance illusion of functional pieces. Jon Havener attempted to connect the past and present with dimensional compositions that control space, form, surface, and visual movement. Mary Lee Hut stunning twined and fabricated gold choker incorporated more forms of negative space than her past work.

"Contemporary Metalsmithing: Behind and Beyond the Bench" was an exceptional opportunity to explore the past, present, and the future of contemporary metalsmithing and to contemplate the dynamic artistic and technical development of individual metalsmiths. As an informative, introspective exhibit, it paid tribute to the creative talent, discipline, and the generous exchange of ideas within the metalsmithing community today.

Noel Leicht is a metals artist and writer from St. Louis

The Telling of Stories: Narrative Jewelry and Fiber

The Society of Arts and Crafts

Boston, Massachusetts

August 6 - September 11, 1994

by Julia Jiannacopoulos

To narrate is to recount, report or relate something like a story or a tale. This highly diverse exhibition of narratives functioned on many levels and successfully presented socio-political commentary, elicited personal introspection, and considered aspects of human spirituality. Curator Gail Brown, a Philadelphia writer and private crafts dealer, invited: Candace Beardslee, Keith Lo Bue, Enid Kaplan, Keith Lewis, Elizabeth Chenoweth Palmer, Beverly Penn, and Rhonda Shikanai to participate. The imagery ranged from the Disneyesque, as in Shikanai's work, to the historical in Penn's, to the revelatory and confrontational in Palmer's and Lewis's brooches. In addition to traditional precious materials, materials such as insects, animal and human hair, century-old newspapers, and maps found their way into the work in a credible and refreshing manner.

There is a certain naiveté and looseness in the work of Elizabeth Chenoweth Palmer, Keith Lo Bue, and Enid Kaplan. These qualities allowed the poetics, history, and associations of the materials to facilitate the narrative. This was prominent in Palmer's rather large pins (3¾" - 5½") which included both precious and non-precious metals juxtaposed with feathers, stones, glass, and maps. In Getting On Down The Road and Man With A Bird On His Head her unique iconography combined child-like renderings of menacing adult figures with images of small children. These images manifest a child's experiences of physical, mental, and emotional abuse and the viewer can imagine these works as highly charged drawings done in therapy to facilitate a child's healing. The thought of wearing these 'badges' forces the viewer to re-consider the images, messages, and implications and then to determine if one possesses the courage to confront the world wearing such statements.

Keith Lo Bue's constructions appeared greatly indebted to the work of Joseph Cornell, complete with marbles, until one viewed his jewelry. Collectively and appropriately entitled Oddments, the works lure viewers into a diminutive diorama through the maneuvering and motion of the 'trappings' inside the jewelry. The interiors captivate and disturb and the objects must be fondled to be experienced. The brooch format allows one to possess and wear a tiny environment full of fragments and metaphors for time, place, and memory.

Due to her knowledge of the meaning of gemstones and her interest in a 'primitive' aesthetic, Enid Kaplan was an easy choice for this show. Her extensive knowledge of materials and their symbolism is impressive but does it successfully convey her intentions in the work? Does the work need the support of the text to validate the use, placement, and relevance of materials? This viewer also questions her offer to sell parts of a work separately from one another, as in Water Weaver. Is it credible to offer to sell an amulet separately if it is displayed in a meaningful, sculptural environment?

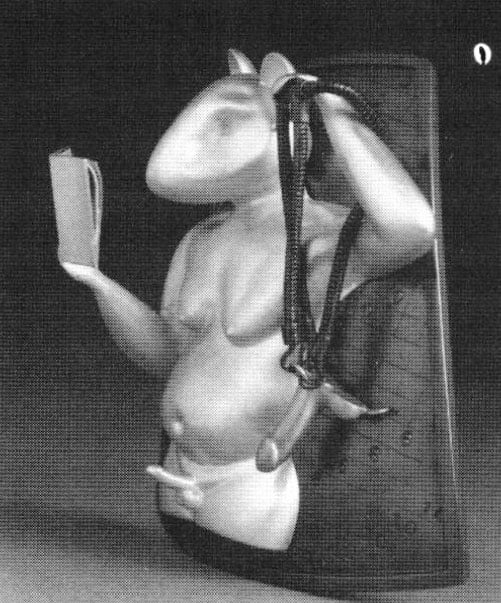

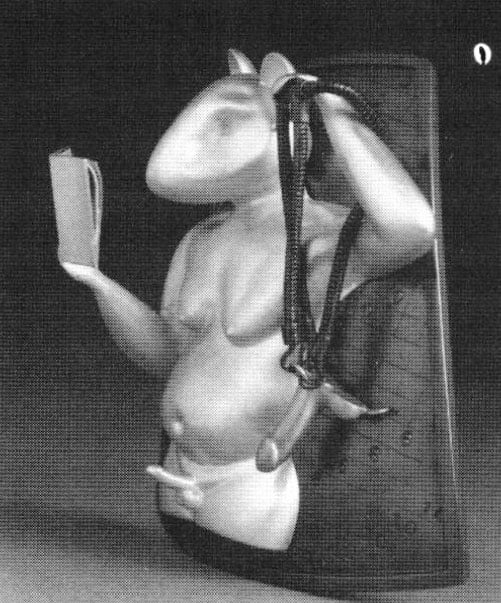

As in many exhibitions, there were artists who stood apart from the group. The integrity involved in the concepts behind both Keith Lewis's and Beverly Penn's work is indicative of the thought process of the makers. In Lewis's new work, Building Self and Well Doug…Its 36 now, he reveals human inadequacies and liabilities using the symbolism of a man depicted as a mouse and a dog respectively. In Building Self, four beautifully detailed 'strap-ons' framed on the back of the brooch added an element of sardonic humor that could be either self-referential or serve as a social metaphor. The idea of 'two-sidedness' in both brooches augments the dual meaning and invites viewer's introspection. This duality of image and idea also relates to Beverly Penn's Venus and Veneration series. Her iconoclastic approach to the depiction of women throughout art history, engages the viewer conceptually, holds them formally, and follows them home metaphorically. The Veneration series references the spiritual and private intimacy of altars and niches. This combination of architectural spaces, natural forms, and milagros (miracles) represent the desire to return absent body parts to familiar, female icons. These brooches also pose questions for viewers regarding nature versus culture. While the two series shared similar historical content the Veneration series appeared more intrinsically cohesive.

With its broad range of narrative styles "The Telling of Stories: Narrative Jewelry and Fiber" succeeded in being a well-attended and worthwhile exhibition. If the level of content in the work of the selected artists had been consistent throughout, this show would have been ranked in the realm of the exceptional.

Julia Jiannacopoulos is a metalsmith who lives and works in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Metalsmith ’89 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

1984 Jewelry International Exhibition: Observations & Review

GZ Art+Design 2003 Spots

Metalsmith ’89 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.