Metalsmith ’96 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

16 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1996 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Helen Shirk, Arline M. Fisch, Thelma Coles, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Textile Techniques in Metal

Mobilia Gallery

Cambridge, MA

February 6 - February 28, 1996

By Patricia Harris and David Lyon

Arline M. Fisch is the first to admit that she did not invent the use of fiber techniques in fine art metalwork. But she did write the 1975 touchstone book on the techniques from which this exhibition draws its title and, less directly, many of its pieces. Although Fisch's original publisher let the book go out of print in 1985, interest remained strong, prompting the artist to redo the volume for Lark Books in an expanded and updated edition in 1996. The exhibition at Mobilia, which represents many of the artists Fisch highlights in the new version of Textile Techniques in Metal, celebrated the publication with a show of technical tours de Force by Fisch, some of her former students at San Diego State University, and other artists employing textile techniques covered in Fisch's book.

Exhibitions arranged around technique often suffer from a sameness of the art - thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird still produces lots of blackbirds. But the Mobilia gathering illustrates the diversity of form, style, and vision possible with textile techniques in metal. Fisch admits that in her own jewelry, she is not drawn to "the hard-edged surface. I've always liked things that take a more expressionistic attitude toward the metal." Intrigued by textile techniques in metal that she found in other cultures, Fisch reinterprets them in a contemporary context to expand the possibilities of expression - an attitude she seems to pass on to her students.

The exhibition, like the book, was dominated by Fisch's own work, in part because she has experimented more than most artists. "Basically, I explored everything I already knew or could learn to do in yarn", she explains.

"Some were successful, some too labor-intensive, some wonderful. I've never enjoyed doing things that are punishingly long." Among the techniques represented are weaving, plaiting, crochet, hairpin lace, basket techniques, bobbin lace, knitting, and spool knitting (using rings from Barbie knitting doll kits).

For the moment, Fisch has largely settled on handknitting to create voluminous, almost gossamer forms that nod to traditional decorative fiber in formal ruffled collars, for example. Knitted from colored copper wire, these pieces share characteristics of metal (the ability to hold a form) and textile (a soft hand and drape).

Basketry techniques also figured strongly in Fisch's work in the exhibition, especially silver strips twill-braided into sash-like cloth or constructed into square forms. By using bright and oxidized strips in the braiding (and in woven silver as well), she elicits the patterning effects typical of colored textiles. (Fisch generally produces her strips by flattening wire in a hand rolling mill, preferring strips to wire for a larger reflective surface.)

Fisch's own work has such a distinctive inevitability that it is surprising how different work by her students can be - perhaps a result of Fisch's emphasis on experimentation rather than imitation. Danish metalsmith Guldsmed Hanne Behrens works principally in heavy-gauge wires (often 18k gold and oxidized sterling silver) in very tightly woven forms that create dense, nearly solid pieces with the seeming durability of medieval chain mail. Of all the artists selected for this exhibition, Behrens most delights in playing the airiness of metal textile against the weight of solid Frames and attachments.

In a related approach with strikingly different results, Stuart Golder creates extremely detailed loom-woven elements of 14k and 18k gold which he then assembles into a grid structure fabricated from sheet metal. The completed pieces of jewelry harken back to African and South American decorative gold that was lost-wax cast from models of fiber probably impregnated with wax. But because Golder's pieces are originals rather than replicas one generation removed, he is able to maintain even finer detail.

By their nature, textile techniques lend themselves to abstraction, but one sculpture in the exhibition also demonstrated the potential for whimsical representation. Paula Wolfe's strawberry basket replicates the traditional splint basket in strips of sterling silver - an object she fills with lifesize (and lifelike) ripe strawberries crocheted in coated copper wire.

Nova Scotia weaver Dawn MacNutt capitalizes on the self-supporting qualities of wire structures with hieratic sculptures suggestive of wrapped human forms. The Mobilia exhibition featured one of her small pieces, about eight inches tall, woven of fine silver and copper wires. MacNutt is perhaps better known for similar life-size structures woven of copper wire warp and natural seagrass weft - a combination that entirely blurs the line between material and technique.

Speaking of textile techniques in metal, Fisch says, "I didn't invent it. I don't own it". The multiplicity of expression in the Mobilia exhibition speaks to Fisch's success in providing a written resource as a point of departure for other artists.

Patricia Harris and David Lyon write criticism and art features from Cambridge, Massachusetts. They are co-authors of Michael James: Studio Quilts.

Issues & Intent Contemporary American Metalwork

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, CA

January 2 - February 3, 1996

By Tran Turner

Women of America, "if you're raped, you might as well relax and enjoy it, because no one will believe you".

When one reads a loose-cannon pronouncement like the above and there isn't additional information, perhaps a quick visceral reaction sets in. What exactly is the issue here and what is the intent? If one finds themselves drawn into this ridiculous statement, it is likely that their preconceived gender-specific notions have already kicked in at high speed. Is this diatribe a statement of male dominance exerting the rhetoric of testosterone or is it feminist critique putting it in your lace as an attempt to overthrow a synthetic intellectual inferiority complex? In either case, the emotionally charged internal drama one may feel as the result of this careless expression about rape can be a highly consuming one. Such an inflammatory statement could not possibly result in a consensus which situates everyone on an even playing field. Though this is not to say that you might just as well have no care about it whatsoever.

Issues & Intent Contemporary American Metalwork, another aggressively conceived albeit sophisticatedly presented show by Susan Cummins Gallery, established a similarly defined divide and conquer set of conditions (minus the criminal derision but filled with action-related aspirations). There is no mainstream or equal footing in this exhibition. But then again, the show stressed the idea of promoting critical themes. While the show included 46 objects by the same number of artists and carried a broad thematic guideline to champion "a belief in the humanistic versus the machine made" and to honor "the craft tradition even while questioning it", it proved to be more like a complex foreign film examining a diverse class structure with numerous idiosyncratic stories, coupled with difficult to read subtitles. There were so many vantage points from which to view this exhibition that one wondered: What the hell was going on: confusion or absolute intrigue? Fortunately, the curators in charge made it the latter. Its too bad this exhibition did not travel to a minimum of ten other venues around the country.

Unquestionably, the unstated intention to establish a political platform for the show was paramount, so much so that the relevance of the individual works of the artists featured immediately took a back seat. Everything became attached to the overwhelming power of this metals gathering as an avenue to introduce a material-based counterculture, making the exhibition as a whole a collective bargaining force; but to what end? Granted, the literal side of metal as metal was broad based, whether represented by outstanding works in jewelry by Susan Kingsley, Kiff Slemmons, Arline Fisch, and Mary Lee Hu; vessels by June Schwarcz and Helen Shirk, sculpture by Gary Griffin, Harriete Estel Berman, and Chris Ramsey; or the general interest in utilitarian objects exhibited by Jonathan Vahl, Marilyn da Silva, John lverson, and David Clifford (furniture and architectural components were noticeably absent).

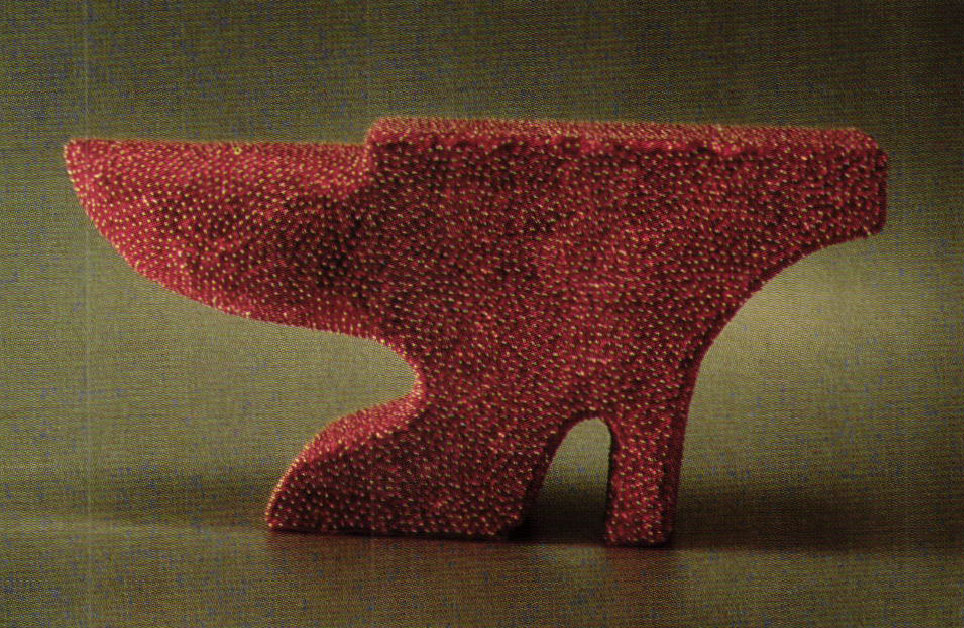

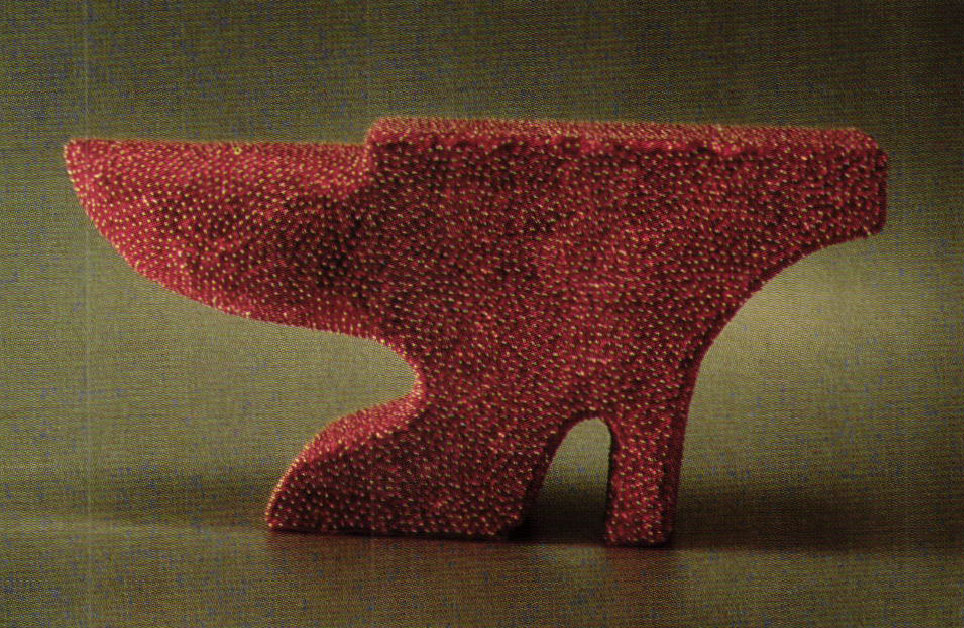

On the flip side, or more appropriately the side spelling out the subtext, the show entered upon a conceptual little-if-no-metal fault zone by unhesitatingly including work like Erika Ayala Stefanutti's You Call That Work: Craft Tool. Created from decoupaged Styrofoam, plastic beads and sequins, the piece represented a glittering red anvil. What' up with this? In her artist's statement, Stefanutti stated that her work "can be understood as belonging to professional metalsmithing because of the references to metalsmithing tools". Okay, but take it out of the framework of this exhibition and conduct a poll. Keith Lo Bue's Unknown Female Head, predominantly made from painted wood, glass, and various non-metal components, stood as a framed construction or what he called in his artist's statement a "fabricated environment". Displaying a photographic image of a late nineteenth-century woman whose mouth is confined by some experimental scientific apparatus, Lo Bue's intent was to preserve the past in such a way to evoke ineffable stories. This one's a bit more difficult to grasp because there was no visible interest on the artist's part to even conceptually reference the metals field, unless you count the silver content in the photograph and the found-object brass rod among the additional beads, crab claw, bone, mirror, and crushed glass.

Joyce Scott, conversely, at least used metal wire to hold her glass piece together. Called Date Rape, this lamp worked and blown glass sculpture certainly fit right in with the other openly expressed agenda for the show - to stand as a reaction to Sculptural Concerns: Contemporary American Metalworking (shown concurrently as a traveling exhibition at the California College of Arts and Crafts). Actually, all of these materially defiant works provide a hard hitting reaction to Sculptural Concerns. This also included Kathy Buszkiewicz's bracelet produced from 265 $20 bills, which, she pointed out, maintains the power of money even after the paper currency has been altered (a bargain at $1,700 after you add it up). Bruce Metcalf and Leslie Leupp both turned in mixed media wood sculptures, although admittedly they used metal components to enhance their chances. And of course, Metcalf is Metcalf.

But where does all this take us? Although the examples in the exhibition comprised of alternative slug-fest materials were small in number, their forceful presence in conceptual forms comprised of wood, paper, plaster, glass, plastic, photography, and mixed non-metal materials generated a strong politically challenging elbow to the gut. The bold move to disregard the core dictate of only showing work that is dominated by the material and technical relationships of metal itself certainly produces a serious division in the expectation we should have about what exactly is current American metalwork. This is definitely a formative aesthetic breakthrough for how artists can work within the arena of contemporary metals, not to mention the entire crafts field. For a moment let us forget how a material, in this instance some type of metal, can lend itself to self-prescribed medium specific outcomes as framed within the general classifications of jewelry, vessel, sculpture, furniture, utilitarian object, or architectural component. Instead think about the capability of an artist to reverse the need for a work to be dependent upon a particular material to be medium specific. This is a provocatively fresh conceptual criteria for coming up out of the traditional trenches. Susan Cummins Gallery, unwittingly or intentionally, has somewhat clarified this new approach while still putting on a really good metals show.

Tran Turner is the Curator of Crafts at the Oakland Museum in Oakland, CA.

- Issues & Intent Contemporary American Metalwork. (exhibition announcement), Mill Valley, California: Susan Cummins Gallery, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Helen Shirk: Contemporary Jewelry 1970-95

Helen Drutt Gallery

Philadelphia PA

November 8 - December 2, 1995

By Bruce Metcalf

This exhibition of Helen Shirk's jewelry was unusual in that it included Shirk's work from as far back as 1970, along with a group of brooches from the past five years. However, it wasn't a true retrospective: none of her silver and titanium jewelry from the early 1980s was included, nor were any of her vessels. Nonetheless, the two disparate groupings of jewelry made for some interesting comparisons.

The first group consisted of necklaces and bracelets made between 1970 and 1980. They started out in the once-familiar Indiana University constructivist style of juxtaposed line, surface, and mass. These works were interesting both as historical material, and for the skill with which Shirk adapted pure abstract forms to jewelry. The group also traced Shirk's gradual evolution towards a more personal style. The last work from this period, a pair of bracelets from 1980, showed how she distilled the busy compositions of the I.U. style into a few textured surfaces with varied edges, and a few subtle connections. They made the earlier work seem overstated.

The new brooches, made in 1991, 1994, and 1995, were as abstract as the early work, but decidedly more organic. The pins consisted of assembled strips of silver and gold, somewhat like a loose bundle of feathers. Each strip was textured with hammer or file marks. Color variation was minimized; in comparison to Shirk's titanium and silver jewelry from the 1980's, these pins were almost monochromatic. A few of the later brooches had several strips pierced with small, irregular holes, giving each pin a subtle see-through effect that heightened both texture and contrast. When worn, Shirk's new pins looked like irregular metal corsages, and were surprisingly dramatic.

Bruce Metcalf is a metalsmith and a Contributing Editor of Metalsmith magazine. He lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.

Enamel Guild/Northeast

Community Arts Center

Wallingford, PA

By Dr. Geraldine Velasquez

The Enamel Guild/North East exhibition at the Community Arts Center in Wallingford, Pennsylvania. happens to coincide with an exhibition of Faberge in America at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is easy to see from both exhibitions why the enamelist's art is so popular and enduring. Lustrous, luminous, translucent layers of colors are built upon and between, metal wires or on a metal support. Light shines through the glass enamel or off the highly reflective surface. We are accustomed to seeing color this way, every time we view our TV and computer monitors. And because of this, enamel art has a contemporary appeal in a way that flat, non-refractive pigment based works do not. The colors seem charged with electricity as they vibrate off the surface. Yet they also have a sense of depth, as in old master paintings which were constructed of translucent layers of oil paint.

A review of the works in the Enamel Guild/North East exhibition reveals qualities in common with the famous Master Enameler Faberge. Labor-intensive metalwork structures support the enamel surface and creates repetitive patterns and details which are the hallmarks of enamel. Intricate armatures and engraved metal supports are visible and share the glory along with the surface. Such techniques, such time-consuming processes, are reminders that man toils in the service of beauty. And we are struck with awe. This very craftsmanship transcends craft and imbues the work with grace, a quality all too lacking in contemporary art.

Notable from the work of the thirty-eight artists in this exhibition is the continuity with enamel traditions using processes such as cloisonné, plique-à-jour, and grisaille. Ritual vessels, jewelry, and hanging objects by Valeri Timofeev, Marilyn Druin, Kay Whitcomb, Isabella Corwin, and Carin Preston are particularly noteworthy in their outstanding designs achieved through complex processes.

Timofeev, Druin, and Whitcomb integrate surface design with the shape of the vessel to present harmonious cups and bowls with ritualistic connotations. Timofeev, a recent immigrant to this country from Russia, is the most classically trained. The virtuosity of the metalwork and countless patterns of applied color keep the viewer entranced with his work. To this observer, however, he is undergoing an Americanization in color and design since his earlier exhibition at the International Enamelist Society Conference in Virginia. His surfaces of amazing complexity are becoming more stylized and his colors, which were softer then, are tending towards more primary hues. His vessels remain dazzling nonetheless.

Marilyn Druin's jewelry and goblets are more medieval in presentation. Deep reds, cobalt blues, and the heavy use of gold within ovoid shapes seem to convey almost magical properties. One wants to wear her objects as talismans to ward off evil. Kay Whitcomb's more modern sense of design reminds us of the pleasures of the decorative surface. Refinement comes from clean, pleasing patterns devoid of the clichés that so many crafts artists use.

Best among the wall-hung works are Isabella Corwin's fragments. Her Celestial Shrimp and, Piscara exploit the additive and subtractive possibilities of the metal and enamel. We see growth and decay in the image of shrimp. Translucent shells can be a metaphor for the process of enamel itself. In the irregular edges around the shrimp, uneven layers of enamel are exposed to reveal the carpus being shed. And in Piscara the metal wire supporting the enamel breaks through the surface. This image subtly reinforces the above-and-below nature of the art. We are aware of the fusion of the enamels through the aggregation of rich colors even while the creature appears to decompose. A highly intelligent mind and hand are at work here.

The exhibition reflects a current trend of contemporary craft: that content and means of expression have an unresolved relationship within the object. The fact that the many of the images are not necessarily best expressed through enamels, though pleasing to those artists who believe they transcend the craft of their art, only enriches by comparison the works of those noted above. The decisions and problem solving, the paring away the unnecessary while mastering the essential, the techniques inherent in metalsmithing and enameling, in evidence are the qualities that make these works outstanding.

Selected works from this show are to travel to the New Jersey Designer Craftsmen Gallery in New Brunswick, New Jersey in March.

Dr. Geraldine Velasquez is Director of The Forum for Research and criticism in the Crafts at Georgian Court College, where she is Professor of Art. Dr. Velasquez has published articles on her research on the attitudes and belief of contemporary craftspeople in The New York Times, The Crafts Report and the Boston Globe. She has been an Evaluator for Crafts Fellowships for The New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Helen Williams Drutt Collection of Modern Jewelry

1989 SNAG Conference Review

35 Years of Electrum Gallery

The San Francisco Metal Arts Guild

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.