The Metalwork and Jewelry of Harry Bertoia

15 Minute Read

Harry Bertoia was not simply a metalsmith or a furniture designer, sculptor or printmaker, artist or craftsman. He was all of these. Apparently unconcerned with the barriers that had been assumed for years between art and craft, esthetics and function, creativity and commercial success, he balanced as subtle, evocative esthetic vision with practical design solutions.

Some of his sculpture functions as fountains. His chairs are sculptural forms designed to hold the human body. The jewelry is literally sculpture to wear. Many of his most minimal, modernist works make music. They are all abstractions, or rather extractions, from nature, suggestive of fields of grain, shooting stars or plant forms, perhaps, but always with multiple interpretations relative to scale, color, movement and sound.

Harry Bertoia was born in 1915 in the village of San Lorenzo in northeastern Italy Emigrating as a teenager with his father, first to Canada and then to Michigan, Harry was reunited with his brother Oreste, who had settled in Detroit earlier. After some difficulty learning English, Bertoia entered a special program for artistically gifted students at Cass Technical High School in Detroit. There he pursued his childhood interest in drawing and painting and received his first training in metalsmithing. A scholarship enabled him to attend the School of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts for one year to study painting and drawing. In 1937, on another scholarship based on the metalwork he had done at Cass, he entered Cranbrook Academy of An in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Cranbrook had an enormous impact on Bertoia. It was here that he met his future wife, Brigitta Valentiner, daughter of a renowned an historian, as well as colleagues Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen. The independence fostered at Cranbrook would stand Bertoia in good stead for the rest of his life, freeing him to explore all aspects of design. He did not attend formal classes in sculpture, but he did have a great deal of contact with Carl Milles, the resident sculptor, and ceramist Maija Grotell. At Cranbrook, Bertoia concentrated on monoprints, drawing and jewelry. Like the work on paper, the jewelry is abstract and organic in inspiration, with an interest in surface texture.

As part of his scholarship obligation, Bertoia was to oversee the metals shop, which had been neglected since Arthur Neville Kirk's departure in 1934. This probably entailed a general supervision of students who wanted to experiment with metals, as Bertoia's own training at this point must have been only in the basic metalsmithing techniques. His reaction to this opportunity is characteristic of his quiet confidence: ". . . This appealed to me very much because I saw some of the tools that were there and when I see tools I want to get busy with them." To a great extent, Bertoia seems to be self-taught, an extraordinary accomplishment in light of the technical skill evident in his work. Only one year after arriving at Cranbrook, he was appointed Metal Craftsman, a full-time teaching position.

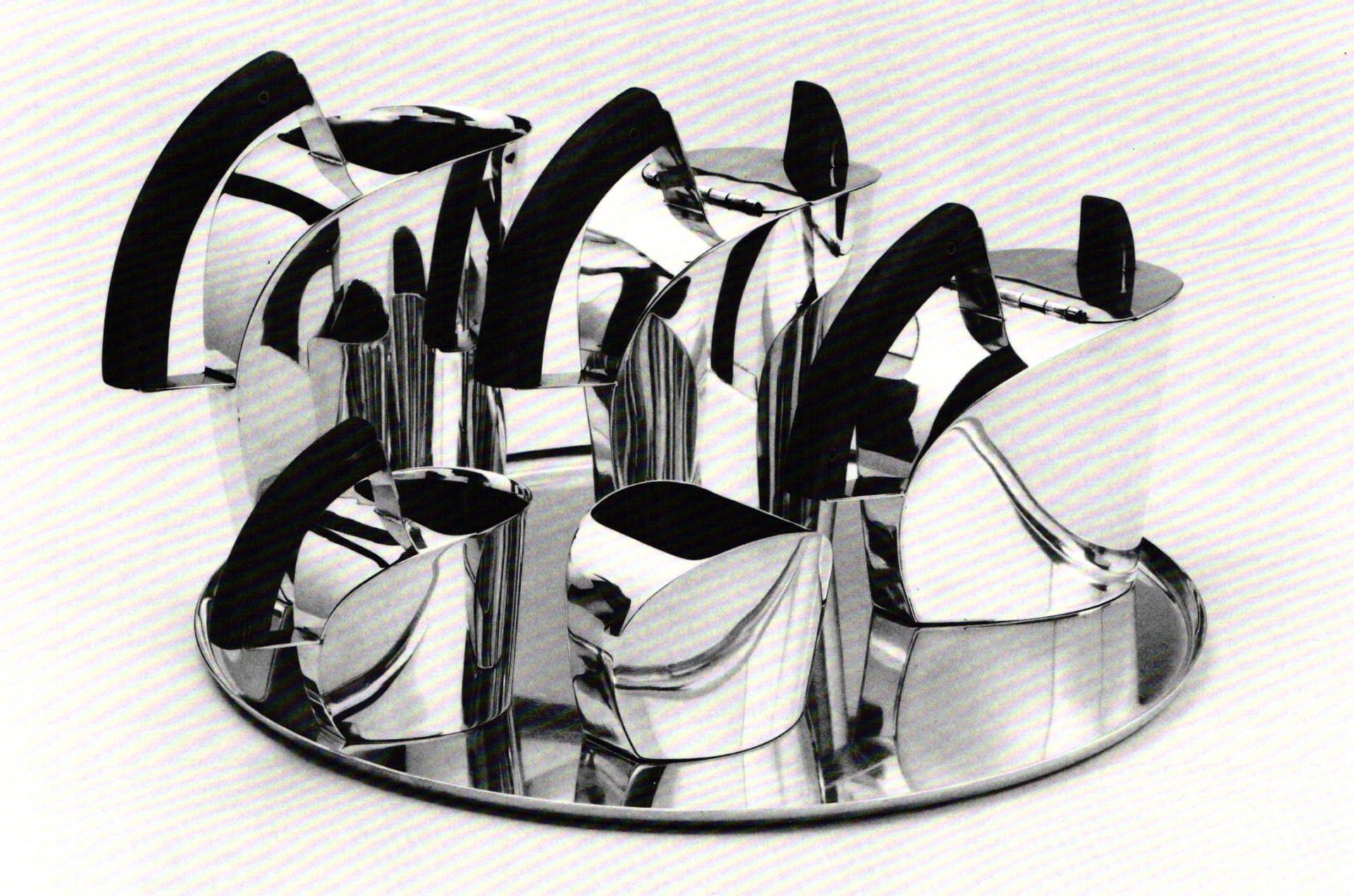

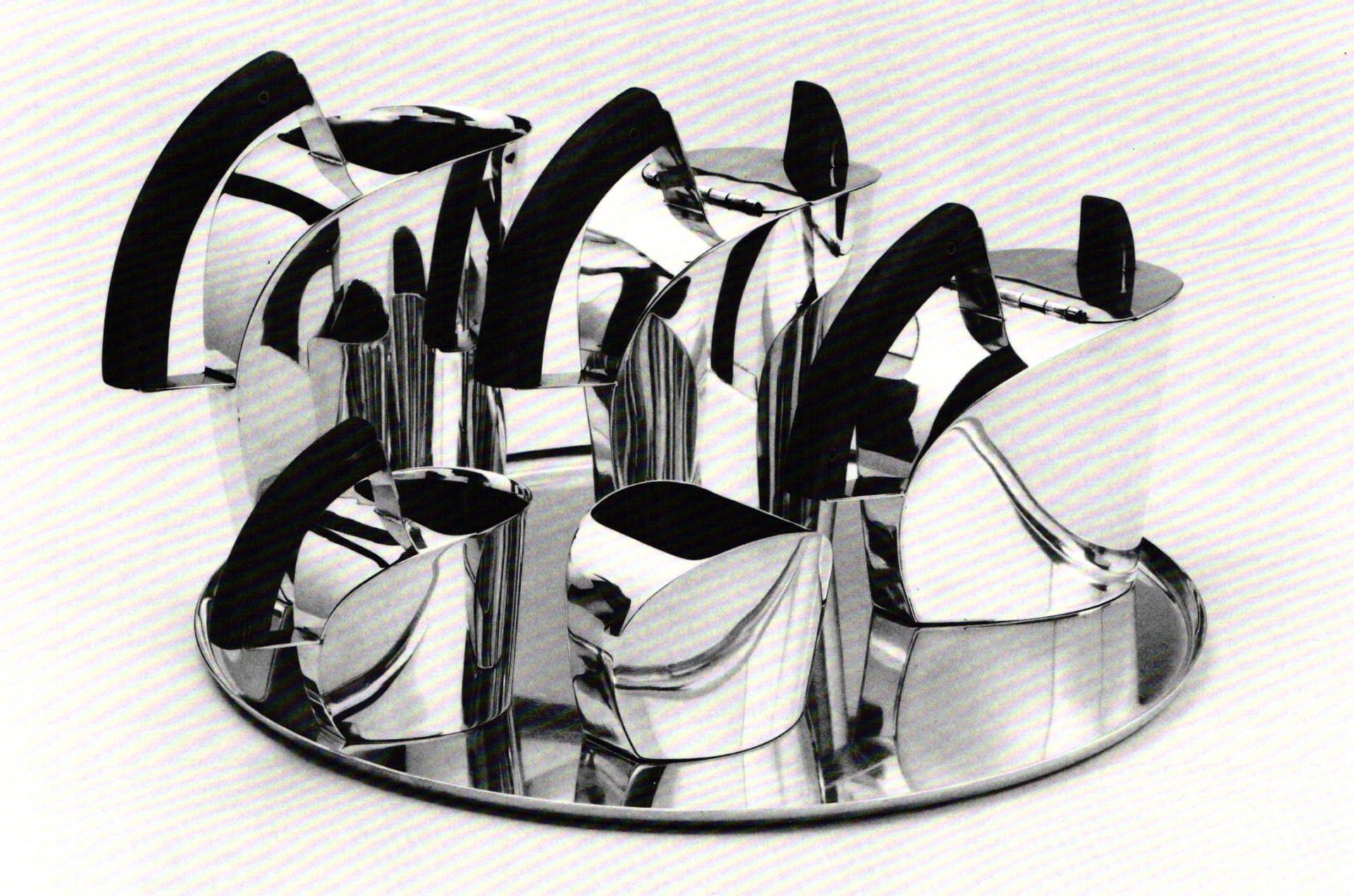

Bertoia's metalworking had been limited to jewelry at Cass, but Cranbrook's equipment enabled him to produce holloware as well. One of several coffee/tea sets he made is now in the collection of the Cranbrook Academy of Art Museum. With their clear, clean, silver surfaces, the vessels almost seem sliced from solid blocks. Their high polish fits within the 1930s and 1940s esthetic of Eliel Saarinen (Director of Cranbrook from its inception in 1925 to 1946) and other Scandinavian modernist designers. This service and the Kamperman service, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts, seem too impersonal, too resolutely unadorned to relate to Bertoia's work as a whole. Although produced with consummate skill and a sophisticated sense of design, they do not emit the evocative mystery that surrounds his other work in jewelry and large-scale sculpture.

There is no doubt that Bertoia was fascinated with surfaces. A bronze vase made about 1940 shows clearly his interest in the purely reflective nature of metal. The highly polished golden surface undulates in repetitive, soft angles, distorting the reflection and causing the whole piece to move with an organic sense of growth The coffee/tea sets and this vase indicate one extreme of surface treatment that Bertoia explored and then abandoned in favor of more subtle finishes It may have been his interest in surface texture that drew him away from holloware, for he produced it only during his Cranbrook years, 1938 to 1943. On the other hand, practical considerations probably contributed to this disinterest. In the spring of 1943 the Cranbrook metal shop closed and shortly thereafter Bertoia left for California and design jobs in defense industries. Bertoia's jewelry production, on the other hand, extended throughout his career and may have served as small-scale studies or sketches of ideas and techniques. The jewelry is improvisational by nature, freely exploring ideas of space, texture, movement and a kind of organic liveliness difficult to translate into larger pieces.

During his tenure at Cranbrook Bertoia peddled his jewelry around campus in the studios and offices. As the war effort escalated, metals became increasingly difficult to obtain. Much of the early wire jewelry, reportedly, was made from scraps found around the metal shop. A series of brooches comprised of delicately hammered sections of wire was produced in 1942-43. Flattened at each end, soft, faceted petal shapes were joined along a spine or clustered together with tiny rivets, suggestive of wavy, underwater flowers or sea creatures. The reference to natural forms is broad and can never quite be grasped or identified. These designs are, in the final assessment, abstract and nonrepresentational, but so evocative and mysterious as to trigger some half-forgotten, distant memory. They relate to the humorous and yet vaguely unsettling vision of Paul Klee or Alexander Calder.

The series culminates in the elegantly whimsical Ornamental Centipede of about 1942. Here Bertoia expands his jewelry scale, which was frequently quite large, to a nonwearable size. Ornamental Centipede was intended as a kind of table centerpiece. With its flexible joints and tactile surfaces, it was certainly meant to be handled and rearranged. Here the faceted petals are attached as vertebrae to a spinal column, forming a swimming/crawling creature of primal construction and delightful nature.

Other hammered pieces include a necklace and belt made in the 1940s of square, slightly domed links. The surface texture so carefully produced in this case contradicts the smooth, uninterrupted gloss of the earlier coffee/ tea services. Repetitive, slightly varying units held Bertoia's interest throughout his career. The early jewelry composed of similar but individualistic hammered wires, the square links of the necklace and belt, underscore a design philosophy Bertoia used to produce his well-known chair design for Knoll Associates (later Knoll International) in 1952. Like the work on paper and in metal, the chairs are based on a repeated module, which, in turn, determines the shape of the whole, ". . . like a cellular structure."

After his marriage to Brigitta Valentiner in the spring of 1943, Bertoia moved to California to collaborate with his friend Charles Eames on the design for what would become the famous Eames chair produced by Knoll. In 1950, largely as a result of his involvement with the Eames chair, Bertoia was invited by Knoll Associates to become part of a rather unique relationship between industry and art. Bertoia was to join the Knoll staff but work independently on his own designs. His arrangement with the company offered Bertoia the financial security he needed to continue with his work while supporting his growing family. The Bertoias moved to Pennsylvania in 1950 and Harry established a studio in Bally, near a Knoll factory.

Typically, Bertoia approached furniture design with consistent logic and imagination. He used his experience in sculpture—his formal interests in modular form, manipulation of light and space and clarity of structure—ordering them for the first time to a functional application.

In the sculpture, I am concerned primarily with space, form and the characteristics of metal. In the chairs many functional problems have to be satisfied first . . . but when you get right down to it the chairs are studies in space, form and metals, too.

If you look at these chairs, you will find that They are mostly made of air, just like the sculpture. Space passes right through them.

After first persuading Knoll to establish a metals shop in their previously solely wood-oriented factory, Bertoia researched human posture and movement and selected the diamond as the modular unit most suitable for his chairs. Bertoia's frank practicality: "A Chair is designed as much by one's behind as one's head" was united with a demanding esthetic.

He used materials in chair design, as he had in all his other work, to suit his purpose, not hesitating to cover the structural elements with another color or texture.

I wanted the chairs to fit as comfortably as a good coat. For flexibility in the basket construction, I used steel for strength and unified the design with nickel-chrome plating for beauty, giving the chair durability and lightness in appearance.

Bertoia perfected a system for coating steel rods with molten metal for texture and color impact. Using this technique, he transformed an idea for a suspended sculpture to produce one of his most extraordinary commissions. Sunlit Straw, 1964, a wall sculpture for the Northwestem National Life Insurance Company in Minneapolis, is a golden tangle of metal sticks, with turquoise oxidation. Each steel rod was drawn individually through molten brass alloy.

Bertoia experimented continually with various metals, alloys and techniques—spinning. Welding, fusing, gilding, lacquering, enameling, even spill casting. He often painstakingly finished the sculptures alone, after his assistants had left the shop for the day, polishing, cleaning and applying just the right patina. He used industrial stock—shot, rods and sheets of metal—whatever was most appropriate to his needs.

Good design takes advantage of all the developments in technical facilities and materials. It accepts and uses the findings and revelations of other men. Yet good design's essential response is toward nature . . . to natural forms and tendencies that the designer perceives, reacts to, even stumbles upon in his investigation of an idea . . .

Working in a series allowed Bertoia to refine certain ideas. The last in a series of three fountain designs was commissioned for the courtyard of the Manufacturers and Traders Trust in Buffalo in 1968. It was constructed of copper tubes, oxidized and bronze-welded into an indulating, robust form, organic in inspiration. Unlike Sunlit Straw, the fountain uses a solid membrane to define a surface, rather than a series of points.

In the 1970s Bertoia produced many small-scale studies that reveal his ongoing interest in welded rods with surface texturing. Very simple in shape-crosses, spirals, cubes-they were Bertoia's way of working out designs, possibly for jewelry. They are constructed of bronze and bronze alloys and are carefully patinaed and oxidized to achieve an ancient, heavily textured surface.

Meanwhile, new ideas were appearing in Bertoia's work in an entirely new dimension—sound. Noticing the musical tones of vibrating metal, Bertoia set out to control these sounds, experimenting with alloys, the shape, length and density of the forms, the combinations of other metals and movement caused by wind and touch. He developed the musical pieces with his brother Oreste, an amateur musician, assisting in controlling the tonal range of the metals. Around 1965 he began assembling musical pieces in his studio for concerts, and in February 1975 he installed the most extraordinary of the "sounding sculptures" at the Standard Oil Company Plaza in Chicago. Banks of freestanding vertical rods are spaced throughout a long reflecting pool to catch the wind as it sweeps across the plaza. As they hum and buzz with the changing wind velocity, they provide a never-ending concert for passersby. At the dedication ceremony, Bertoia himself waded into the pool to "play" the vibrating rods for the audience.

Although Bertoia cannot be considered a traditional metalsmith, his work is inextricably involved with the essence of metals and the fine craftsmanship of the material. He explored and delighted in the metal itself, what it would and would not do, its color, weight, texture , even its sound. His training at Cranbrook reinforced his natural tendency to move easily across boundaries between an and craft and between media, through borrowing and adapting the techniques of one to suit the other.

Bertoia himself summed up his life and work a year and a half before his death in 1978:

"I did not start with a written credo or manifesto. Nor was there a program to be followed. It all came about very slowly. School days exposed me to the hows more than the whys or the whats. Encounters with the work of others were stimulants to broader vistas. Childhood memories, mostly happy ones, persisted. Nature as an influence, always strong. Companionship, love and family, a measure of fulfillment. Social contact and hours of solitude, all incredients [sic] in the process of one's growth. Enthusiastic beginnings and recognition of failures marking as long quest to seek and sometimes find a form, a structure, a sound or a way. A find that would tend to make me feel what I am or one that would cause a change in me, would simply deepen the mystery. Facing a problem, yes. Solving it, more often than not, would prove [sic] evanescent. The acceptance of the reality of the dream as a stimulant and propellant toward achieving the other reality generated an atmosphere of involvement rather than passivity. Immersion into the vast recesses of the mind leading to the realization that the inner world is as immense as the cosmos outside . . . At this eternal moment, I have a gut feeling that awareness of the miracle of life is the purpose of life. I might never know . . ."

"The big pieces are a result of metal knowledge and physical forces; they can be any size, on up and up. . . . They too are part of me, of course; however, I am following certain laws of metal and its reaction to bending, falling, cutting, etc. Thus when these objects are played on by the wind and sun they will move, change shape, but always return to obey the law by which they were created. Smaller pieces are a continuum, but they are, say, working from the inside out, ad infinitum, or infinity, as if you continue on and on and on."

- Harry Bertoia, quotes from a conversation with C.B. West in 1977

"The sounding pieces are sculptural works that produce metallic sounds when acted upon by an external force, moved by the wind, struck or strummed by hand. These sound-producing pieces can be categorized in three groups, varying in form, size and sound: gongs, singing bars and the largest group, vertical clusters of interacting wires or rods attached to a base. The base rests on either a resonation box or dampening cushion, which modifies the sounds. The vertical clusters range from short groups of bristly wire to limber groups of ½ inch rod, some approaching 10 feet tall. The tonality and its duration are dependent on the length, cross section, alloy and intensity of force exerted on the piece. These clusters look and move much like their earthly inspiration—clumps of wild grass or reeds. The gongs, some rectilinear, others amorphous, are cut from plate or are hollow fabrications. These pieces are played by either striking with a mallet or stroking and scratching with felt- or rubber-tipped tools. Of limited visible motion, they emit a variety of sounds. The last group, singing bars, are short lengths of thick bar hanging from the ceiling. Positioned so they swing and clang together, dancing in space above the other pieces, they make clear, bell-like sounds, accenting the activity below."

- Karl Bungerz

| Fountain (bottom left) and details (top and bottom right) Bronze-welded copper tubing, 7x8x12′ Photo: courtesy Theresa Kazmierczak, Manufacturers and Traders Trust Company, Buffalo, NY | |

Large commissioned pieces—fountains, etc.—are more or less finished or predetermined before they are started! Small pieces are ever a creative search for me, indicating how the large pieces will be. Therefore, I have simply to carry them out or execute them—not, of course, in a static state of mind, rather as a challenge. But they are somewhat like a flower which attracts many bees—fixed in time and space—there for many to see, as opposed to my day-to-day pieces which are like a bush, which divides and subdivides, eventually carrying me to many, many individuals.

Notes

- Harry Bertoia interview with Paul Cummings, June 20, 1972. Archives of American Art transcript, p. 6.

- Cranbrook Archives, Alumni Records, Richard Raseman to Harry Bertoia, May 3, 1937. I am grateful to C. David Farmer for bringing this information and other details he uncovered in the Cranbrook Archives to my attention.

- Cummings interview, op. cit., p. 6.

- Cranbrook Archives, Trustees' executive committee minutes, February 2, 1943.

- I am grateful to Miss Marguerite Kimball for her recent insights into Bertoia's work and personality in 1942-43.

- Harry Bertoia, as quoted in "Pure Design Research," Forum, XCVII (September, 1952).

- Joanne Ditmer, "Bertoia Chair 'Made of Air,'" The Denver Post, May 29, 1965, np. Bertoia was to receive royalties on each chair sold up to an agreed-upon dollar amount.

- Daughter Lesta was six and son Val one year old in 1950; another daughter, Celia, would arrive in 1955.

- Harry Bertoia, as quoted in Chairs by Bertoia, Knoll Associates brochure, undated.

- Ibid.

- Joanne Ditmer, "Bertoia Chair 'Made of Air,'" The Denver Post, Sunday, May 29, 1965, np.

- Harry Bertoia, as quoted in "The Creation of an Unusual Metal Sculpture," Minneapolis Tribune Sunday Magazine, January 10, 1965, np.

- Harry Bertoia, as quoted in Knoll International brochure, 1966.

- Harry Bertoia, handwritten letter to Clifford West, February, 1976, Archives of American Art.

References

Harry Bertoia, Sculptor, June Kompass Nelson, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1970

Design in America: The Cranbrook Vision, 1925-1950, Robert Judson Clark, et. al., Abrams, 1983. Essays by C. David Farmer and Joan Marter were particularly helpful.

Unpublished material in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Marguerite Kimball, Brigitta Bertoia, Val and Kylene Bertoia, C. David Farmer, C.B. West, Gregory Wittcopp, Bruce Hartman, Joan Marter, Peter Blume, Robert Cardinale, Martin Eidelberg, Karl Bungerz and Jack Carnell for their assistance with this article.

Susan J. Montgomery is a PhD. candidate in American Studies at Boston University, specializing in decorative arts.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Intimate Abstractions of Rachelle Thiewes

Antonia Schwed A Life of Creativity

The Work of Lilly Fitzgerald

World Mining Report 2005 – Australia

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.