Modernist Jewelers in Los Angeles

In the mid-twentieth century, studio jewelry activity centered around two cities in southern California: Los Angeles and San Diego. There existed distinct differences, in both educational opportunities for metalsmiths and overall style between the two areas. This article will concentrate on Los Angeles and its environs.

17 Minute Read

In many fields Californians have pioneered in advance of the national culture, have set trends, have been copied. As [journalist] Carey McWilliams has said: "What America is, California is, in accents, in italics, for this land is not merely a testing ground, it is a forcing ground."

What we have come to term "modernist jewelry," i.e., studio jewelry conceived and fabricated by a single maker, which was influenced by the tenets of modern art, bean in earnest in the United States during World War II. The movement continued until the late 1960s, when concerns with jewelry's sculptural relationship to the body took precedence and reliance on the fine art canon alone declined. Although pockets of modernist jewelry activity can be traced to most regions throughout the country, New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area have until now been considered the most significant. Paul J. Smith, director emeritus of the American Craft Museum , who incidentally made jewelry himself and traveled extensively and sought out craftspeople in southern California during the mid-twentieth century, stated: "In the 1940s and '50s jewelry activity in California increased as one traveled north."

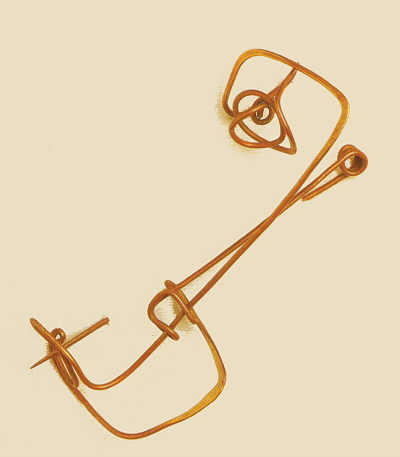

| Claire Falkenstein Brooch, ca 1955 brass Collection Sheryl Gorman Phot: David Allison |

There is little question of the legendary impact in northern California of Margaret de Parts, the most famous California modernist jeweler. [3] Her influence filtered down, furthermore, to makers in the southern reaches of the state, in addition to the rest of the country. Angela Petesch of Los Angeles is just one artisan who credits de Patta with inspiring her to begin making jewelry. De Patta's contribution, however, might not have been as seminal as formerly thought. It has recently become evident that as early as the 1930s there were many other pioneering and influential jewelers working in southern California as well.

Ceramist Glen Lukens, best known for his landmark innovations in glazes, taught courses in ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry making at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles during the 1930s. Famed New York jeweler Sam Kramer, in fact, studied jewelry making with Lukens at USC in 1936, when the jewelry course was first introduced, and it is entirely possible that the silver blobs achieved with staccato droplets of molten metal poured from a crucible and a hallmark of his unique style were inspired be Lukens's dripped and pooled glazes. [4] Noted ceramist and sometime jeweler F. Carlton Ball studied potter with Lukens at USC, receiving his M.A. in 1934. Ball considered Lukens his mentor, remaining an extra year at USC to take the jewelry course. He went on to teach jewelry and metals along with ceramics at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland , anther West Coast institution that trained several of the most significant modernist jewelers, including Irena Brynner. Ball taught at many other schools as well during the course of his lengthy career. Lois Franke Warren studied jewelry with him at a Mills College (Oakland) summer session in 1950.

The catalogue course description for Jewelry Design and Making, taught by Lukens, read as follows: "Fashioning jewelry using semi-precious stones, [enamels] and other new methods of enrichment. A studs of gem materials. Simple processes enabling the student to develop from his imagination the most sensitive and beautiful modern jewelry. Materials provided at cost." [5] The sole prerequisite for the jewelry course was a class in basic design. An article in the May 1933 Southern California Alumni Review touts the jewelry course's effectiveness: "Every teacher who studied the craft … has been successfully placed in a [school] position…. Many students … are now employed in important jobs with … studios." [6] The article additionally emphasized the lucrative aspect of jewelry making: "Materials costing but seventy-five cents may be transformed by a dextrous [sic] worker into an object which would readily sell for eight dollars." [7] According to Susan Peterson, who replaced Lukens at USC, he emphasized gemstones in the course a logical circumstance, since Lukens utilized them in the thick glazes on his square plates. [8] What is undeniable, nonetheless, is that while de Patin, much of whose own oeuvre involved opticut [9] semiprecious stones, was devising a lexicon of modern jewelry in the 1930s in San Francisco, Glen Lukens was training modernist jewelers in Los Angeles.

Sculptor Claire Falkenstein, who lived in Venice , California , from 1963 until her death in 1997 and made a great deal of Calderesque jewelry, also exerted a major influence upon aspiring jewelers from the 1940s through 1970s. Irena Brynner states that a necklace by Falkenstein, which she saw around 1948, when Falkenstein was living in San Francisco , "enchanted" her. "Gradually I became more and more interested in crafts, especially in those crafts which were related in technique and form to sculpture." [10] Falkenstein was one of eight artists-in-residence at an international sculpture symposium, held at California State University at Long Beach , one summer around 1966, during Alvin Pine's tenure there. Choosing to work on a patio abutting the metalsmithing/jewelry studio, she was in clear view of the students. Falkenstein was working on a fountain sculpture, and her methods, in addition to her aesthetic, influenced the jewelry students as well as professor Pine, who was at first daunted and then impressed with her unusual approach to pounding three-inch-diameter copper pipe, on the bare pavement, instead of an anvil, with a tiny eight-ounce ball peen hammer. "For two exhilarating days, [Pine] investigated all the possibilities that squeezing and hammering copper tubing could provide, relearning his own lesson about material prejudice and the value of having an open mind." [11]

| Alvin Pine Neckpiece, ca. 1968 sterling silver |

Where metals education was spotty at best in most parts of the country, and when available usually limited to general crafts courses, immediately following World War II Los Angeles seems to have offered many opportunities for specialized study, through the state system of higher education. Silversmith Hudson Roysher headed a metals program at Los Angeles State College of Applied Arts and Sciences, where Nina Vivian Shelley, Sylvia Ruth Falcove, and Lois Franke Warren (as a graduate student) studied in the 1950s; John Olson, who originally taught at L.A. State as well, founded California State University at Long Beach (CSULB) in 1949, which developed a significant metals department that trained several of southern California 's leading makers.

From 1956-58, CSULB offered courses under the leadership of Ernest Ziegfeld. Ziegfeld, who held an Ed.D. from Columbia University 's Teachers' College in New York City , created, among other designs, eccentric hair ornaments with silver fringes and similar necklaces, examples of which were pictured in "American Jewelry," a special double issue of Design Quarterly, published by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1959, which functioned as an exhibition in print. Ray Hein, who received his B.A. and M.A. from CSULB, studied under Ziegfeld. He taught there himself part-time in 1954, joining the full-time faculty after Zeigfeld left. Hein showed in many national and regional arts exhibitions, including "American Jewelry and Related Objects," originated by the Huntington Galleries in Huntington , West Virginia (1955), where he won the Hickok Award for "excellence of design in a man's piece of jewelry, suitable for machine production." He also participated in the second national exhibition of "American Jewelry and Related Objects" (1956) at The Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester," and the " California State Fair and Exposition" (1963), in which he was ass awarded second place for a silver pin. He taught at Long Beach City College before ultimately taking a position as professor of art at California State University, Fullerton. In 1962 Hein designed the prototype for the "Mercury Pin," created to commemorate the eponymous mission of the first American manned space orbit by astronaut John Glenn.

Expatriate New Yorker Alvin Pine, who received his M.F.A. in metals from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills , Michigan , taught at CSULB from 1962-96, replacing Hein when he went to Fullerton . Although Pine stopped making jewelry in 1972, his influence was profound. Working in an expansive e, flexible, and often kinetic format, informed by his extensive travels, Pine epitomized the individualistic California "frontier spirit" at once sophisticated, "ethnic," and free. [13] Pine's use of lengthy, contiguous dangling wires in his sizable necklaces is reminiscent or brooches by Hein as well as of pieces by Ziegfeld, which is not surprising given their mutual acquaintanceship at CSULB. As a teacher, Pine had a great impact on those fortunate enough to come under his aegis. He counts among his roster of students master jewelers Marcia Lewis Gars Griffin (currently chairman of the metals department at Cranbrook Academy of Art), Carolyn Utter Rodakovich, and Linda Watson-Abbott.

| Philip Paval, Milk Jug, ca. 1948 sterling silver Collection The Newwark Museum |

Henry "Hank" Evjenth graduated from CSULB around 1962. He won first place for a silver ciborium at the "California State Fair and Exposition" in 1963. Although he purportedly specialized in holloware and sculpture, he had a silver necklace and two pendants entered in the fair as well. Robert Trout received his B.A. and M.A. from CSULB. He worked in wood and clay, as well as metal, making boxes, screens, and even furniture. Trout vv as awarded third place for a bronze vessel at the 1963 "California State Fair and Exposition."A necklace and brooch, featured in "Jewelry of the Southwest" (1963-64), display a sillier fringe similar to that seen in jewelry by Ziegfeld Heim and Pine, the de facto "CSULB style." Even UCLA had a jewelry program. Around 1944-46, Lois Franke Warren studied there as an undergraduate with Margaret Riswold, while Marcia Chamberlain was under the tutelage of Warren Carter from 1948-49. There were also opportunities to study jewelry privately in Los Angeles in the 1940s. Sylvia Ruth Falcove and Nina Vivian Shelley took classes with master craftsman Clemente Urrutia.

Between around 1920 and 1965, most independent jewelry studios in the Los Angeles area were located in Los Angeles proper, extending to Long Beach , Seal Beach , Newport Beach , and Laguna Beach . Not all makers were modernist jewelers per se, but all silversmiths working in a modern mode must be addressed and evaluated within this context. Surely, the most colorful metalsmith in Los Angeles was Philip Paval. Born in Denmark in 1899, he underwent a traditional European silversmith's training in his native Nykobing, Falster Island , as an apprentice in the shop of Simon Schultz and simultaneously as a technical school student. After graduation he secured a position at Grand and Lackley, silverware manufacturers, on Crownprincesse Street in Copenhagen . His sense of adventure, however, led him to become a merchant seaman, and in 1919 Paval traveled to the United States, ultimately settling in Los Angeles, where in the early 1920s he opened his own studio/shop, first on Hollywood Boulevard and then on Wilshire. A passionate advocate of the southern California lifestyle, he wrote a poem as homage to the region and its ways, which, though corny, offers a charming glimpse of his romantic disposition:

"Time goes on, one never grows old/Among God's great nature, grand and bold/So let me praise the place I love best/It is California, 'way out west.'" [14] He was lovable, gregarious, hard living, and hard drinking. Through personal charisma as well as metalsmithing skill, he became a self-proclaimed "Hollywood Artist," catering to celebrities such as Rudolph Valentino, for whom he designed a slave bracelet, and Elizabeth Taylor, whose father, gallery owner Francis Taylor, was his close friend. A frequent guest at San Simeon, the retreat of William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies, Paval created candlesticks for the couple as a house gift. Name-dropping aside, Pavel did have several solo and two-person exhibitions in prominent museums and art galleries in Pasadena and Los Angeles . He was represented in many group shows, both locally and nationally, such as the "17th Annual Painters and Sculptors of Los Angeles" (1936) and "Artists of Los Angeles and Vicinity" (1940), both at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; "American Jewelry and Related Objects" (1955), in which he showed a gold and tiger-eye ring; and the second national "American Jewelry and Related Objects" exhibition (1956), in which he exhibited a gold and pearl ring. His work is in several important permanent collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts , Boston and the Newark Museum , which owns a silver mills pitcher donated by Paval after his inclusion in that institution's "The Decorative Arts Today" in 1948. Paval loaned seventeen pieces to the last exhibition. stipulating that all but the din milk pitcher should be sent to America House in New York City to be included in its "American Silversmiths" exhibition after the show closed. Although Paval was mot a part of the crafts community in Los Angeles, through ties vault the state university system, nor (lid he function specifically as a modernist jeweler, and furthermore catered to the stars instead of the beat generation (the most likely audience for modernist jewelry), he nonetheless participated in the venues available to those creating more avant-garde studio metalwork. He was clearly e most prolific and unabashed self-promoter, and although his style was consistent with a kind of generic modernism that alternately incorporated Cubism, streamlining, naturalism and/or abstract neoclassicism, his jewelry could be quite eccentric Necklaces were often huge in scale, decidedly asymmetrical, and surfaced with deep and varied textures and unusual stones. One cannot help but speculate w whether Paval might have created a larger body of cutting-edge jewelry if his clientele was more bohemian and less connected red to the wealthy, fashion-motivated motion picture industry.

| Lois Franke Warren Pendant, ca. 1955 sterling silver, enamel |

Allan Adler was a silversmith who worked in the Arts and Crafts style. His early studies revolved around artisans as diverse Benvenuto Cellini and Paul Revere. As Janice Penney Lovoos has written, "[Adler] expressed his own concept of modern design, influenced by the best of the traditional." [15] In fact, of the fifteen to twenty smiths he employed, several were Scandinavian. Ironically, unlike the Danish-born Paval, who sometimes tool: chances with atypical styling, Adler was firmly rooted in safe modern design. Eudora Moore, them curator of design at the Pasadena Art Museum, in her introduction motes accompanying the "California Design R" filmstrip, refers to hits as a "designer producer" rather than "craftsman producer," [16] even though his pieces were handmade. Although is approach was decidedly commercial, Adler nonetheless turned out a superior product. In the 1950s and 1960s, his shop was located on Sunset Boulevard and was more reminiscent of Chicago concerns such as the Kalo and Cellini Shops than modernist jewelry studios." In fact, he assumed father-in-law Porter Blanchard's early arts and crafts establishment when the latter relocated to the suburbs." Although he made some jewelry Adler produced mostly holloware and flatware, and his emphasis seems to have been on tabletop objects, which constituted two-thirds of his total output.

Of the modernist jewelers working in and around Los Angeles , Esther Lewittes emerges as one of the most engaging. According to Bernard Kesler, chief installation designer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, who worked on the "California Design" exhibitions at the Pasadena Art Museum in the 1960, and 1970s, [19] "Esther was loads of fun … a real `nut.' [20] Like Al Pine, Lewittes came from New York City , where she received a degree from Columbia University 's Teachers' College. While in New York , she also studied industrial design at the Art Students League and jewelry making with a staff jeweler at Cartier. She began making jewelry in the early 1950s and sold her work through stores such as Georg Jensen and America House in New York and Nanny's in San Francisco . Around 1961 she opened a gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles, moving to Melrose Avenue after about a year. She showed her own jewelry as well as other artists' work, in many media. Her stele was mostly three-dimensional and restrained, utilizing both forging and casting, and sometimes incorporating semiprecious stones and wood or ivory. Lewittes sometimes experimented with cutting- edge modes, as is illustrated by a sculptural ring from 1965, which cantilevers over the adjacent finger. Other jewelers who ran their own galleries included Everett Macdonald, whose Laguna Beach shop opened in 1947. Macdonald created open sculptural silver and gold jewelry, often utilizing nylon monofilament within the negative spaces of his pendants and earrings, reminiscent of sculpture by Henry Moors and Naum Gabo.

| Sylvia Ruth Falcove Ring, ca. 1960 gold, pearl |

There were many other accomplished jewelers working in Los Angeles in the mid-twentieth century. Nina Vivian Shelley earned awards each year at California State Fairs from 1955 58 and in 1960. She won two awards, one being a purchase prize, at the second national "American Jewelry and Related Objects" exhibition in 1956 for a silver and ebony pendant on a silver chain. Shelley's work was also featured in "American Jewelry" in 1959. Mary Shigetomi, also a ceramist, lived in L.A. in the early 1960s before going home to Japan . [21] She won first place for a silver and gold pendant at the "California State Fair and Exposition" (1963). Mars Creamer was a student in metals at UCLA in the 1950s, then taught metals at USC in the early 1960s. 22 She showed two hairpins in "California Craftsmen," sponsored by the newly created California Arts Commission in 1963. Jay Louthian specialized in stones. He had a shop on Melrose Avenue in L.A. , where he sold them unmounted along with pearls and ancient and custom-made jewelry. Louthian showed a pair of bronze bracelets and a silver and pearl ring in 1956, in the second national "American jewelry and Related Objects" exhibition.

Several jewelers made their primary living as public school teachers, a common carrel for craftspeople in the mid-twentieth century. Sylvia Ruth Falcove taught arts and crafts in L.A. high schools. Lois Franke Warren, w her taught jewelry making in high school, also wrote Handwrought Jewelry, a "contemporary text for beginning jewelers," in 1962." Franks Warren (along with Falcove), whose book grew out of her M.A. thesis at L.A. State College a photographic essay on forging used enamel as well as stones in her jewelry; she currently holds a graduate gemologist degree from the Gemological Institute of America.

All in all, the contribution that Los Angeles has evidently made to the development of studio jewelry comes as somewhat of a revelation. For the past twenty years, since modernist jewelry has been defined and studied, the San Francisco story has eclipsed that of its neighbors to tile south. The reasons for this are not readily apparent, since Los Angeles had an extremely active and organized metalsmithing community. Perhaps this circumstance can simply be attributed to southern California's "laid-back" temperament. The makers almost seem as if they were just quietly waiting to be discovered. Those I interviewed embraced the prospect of this article with enthusiasm and generosity, grateful for the belated recognition. Let us hope that its publication will unearth still more compelling jewelers from southern California .

| Esther Lewittes Ring silver, lost wax, ebony, ivory Photo: Richard cross |

Toni Greenbaum is a New York Cry-based art historian, specializing in twentieth-century jewelry and metalwork.

- Eudora Moore , California Craftsmen (Los Angeles: California Arcs Commission, 1963), unpaginated.

- Paul J. Smith, interview by author. May 17, 2001 .

- See The Jewelry of Margaret de Patta: A Retrospective Exhibition (exh. Cat.) (Oakland, Calif. Oakland Museum. 1976), Toni Greenbaum, Messengers of Modernnism: American seen Studio Jewelry, 1940-1960 (exh. Cat.) (Paris: Flammarion, 1996). pp. 74-76. published in association with the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts.

- —

- E-mail to author from Claude Zachary from University Archives & Manuscripts, USC, July 10, 2001 .

- John Harrington, "University Features Practical Training in Jewelry Arts,"Southern California Alumni Review,May 1938, p.10

- kid, p. 8.

- Letter to Toni Greenbaum from Marcia Chambehain, June 29,2001 . Chamberlain, a former jeweler, is currently assembling a crafts archive for the Oakland Museum.

- De Patta designed eccentric, prismlike stones to enhance her architecturally conceived mountings and create optical illusions. San Francisco lapidary Francis Sperisen cut them to her specifications.

- Irena Brynner, Jewelry as an Art Form ( New York . Van Nostrand Relnhold, 1979), p. 6.

- Sarah Bodlne, "Benchmark". AI Pine's Conceptual Exploration," Metagmith 9 (Fall 1989), p.37

- Bath exhibitions were sponsored by the Hlckok Company, Rochester , New York and then traveled under the auspices of SITES (Smithsonian I ,tirution Traveling Exhibition Serves)

- Bodine, p.35.

- Philip Paval, Paval. Auto biography of a Hollywood Artist (Hollywood-Gunther Press, 1968), p. 42.

- Janice Penney Lovoos, "Allan Adler," Craft Horizons 14 (November-December 1954), p. 20.

- California Design X, notes to filmstrips of work in metal. (Pasadena, Ca. Pasadena Art Museum, 1968), p. 2.

- See Sharon Darling, Chicago Metatsmiths (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1977).

- Porter Blanchard learned silversmlthing from his father in Boston . He moved to southern California in 1923 and opened his own shop, in addition to teaching at Batchelder's School of Design and Handicrafts in Pasadena .

- "California Design" was a series of exhibitions that showed both manufactured and handcrafted products. It was sponsored by the County of Los Angeles and directed by Eudora Moore in the 1960s and 1970s, The shows were mounted annually at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1954-1962 and then triennially until 1974, when the exposition became an independent corporation. Jewelry was introduced around 1962.

- Bernard Sector. interview by author, June 29, 2001 .

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Luis Franke, Handwrought, waslry (Bloomington, III.: McKnight & McKnight, 1962), p. 8.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.