Nanz Aalund: A Helping Hand

5 Minute Read

Nanz Aalund's career has been far-ranging. An award-winning jewelry artist based in Poulsbo, Washington, she's taught jewelry and metals classes at the University of Washington and the Art Institute of Seattle; served as a designer and consultant for Nordstrom, Rudolf Erdel, Neiman Marcus, and Tiffany & Co.; was associate editor of the former Art Jewelry magazine; and created her own series of instructional DVDs on jewelry-making techniques.

And she owes her success in large part to an apprenticeship— and her grandmother. The apprenticeship took place a little more than 35 years ago, in a "little mom-and-pop jewelry store" outside Chicago, near where Aalund grew up. The owners, two cousins and their wives, had emigrated from Germany after World War II, and Aalund's grandparents—whose families had emigrated a couple of decades earlier—helped them out. Her grandmother shared her skills as a seamstress; her grandfather, an accountant who liked to tinker, helped with repairs around the new immigrants' home. The store owners were so appreciative that, when Aalund developed a passion for jewelry making while in high school, they took her on as an apprentice.

Over the three years of her apprenticeship, Aalund learned various tasks—mill-sizing stock, drawing wire, processing castings. But "the primary thing they taught me was how to refine gold," she says. "They would have me melt down all the bench sweeps and scraps, roll out [the resulting alloy], and put the ribbons in aqua regia so the alloy would dissolve and the gold could be decanted. It was very fi lthy and time consuming, but also exciting— and it really hooked me."

She went on to earn a BFA in metals at Northern Illinois University in 1983, and that apprenticeship not only informed her thesis on the coloration of gold, but also led to her first job: "My ability to work gold was one of the reasons I got hired as a bench jeweler [at Meyers Bros. Jewelry Manufacturer in Seattle, where she relocated after graduating]. I probably would not have gotten as far as I have without that first apprenticeship."

She was also lucky, though: by the late 1970s, the tradition of employing apprentices was already waning, thanks largely to the decline and collapse of jewelers' guilds and trade unions (which promoted the traditional apprentice/journeyman structure). Today, very few apprenticeship opportunities exist. And as Aalund discovered, without that practical, hands-on professional experience, finding a job can be difficult.

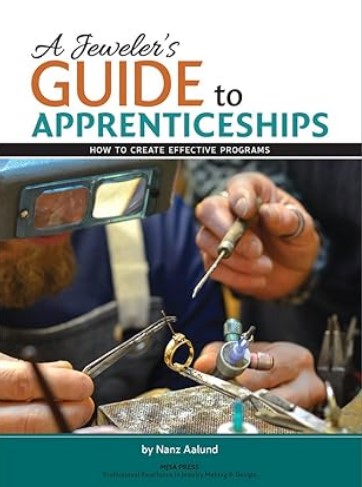

She hopes to counter that with her new book from MJSA Press, A Jeweler's Guide to Apprenticeships: How to Create EffectivePrograms. Written primarily for shop owners but suitable for students and instructors as well, the 208-page book offers insights into all aspects of establishing an apprenticeship program, from how to prepare a shop and choose candidates to, as consulting editor Charles Lewton-Brain puts it, "train that person to work both for you and with you." Its training tools include tool identification and usage tests (with an emphasis on safety), as well as full-color, step-by-step projects to hone basic skills.

Fifteen Years in the Making

The book's origins date back to 2002, when Aalund began graduate studies in jewelry metals at the University of Washington in Seattle. She studied there under Mary Lee Hu, an internationally celebrated jewelry artist whose high-karat gold work uses the weaving technique of twining.

"One of the first things Mary asked me was, 'Why won't trade shops hire graduates coming out of my program?'" Aalund remembers. "Since I was from the jewelry industry, I went back and asked around. I was told that jewelry manufacturers didn't feel the students were prepared for the industry's needs, and that the shop owners didn't know how to train them effectively. "

Both problems were rooted in long-term cultural issues, she adds, which still exist today. The lack of preparation stemmed from the increasing emphasis that universities placed on training creative thinkers and artists rather than production trade jewelers and master goldsmiths.

"After World War II, the state university systems focused on retraining war veterans," Aalund says, and the emphasis was on highly technical jewelry hand skills. However, as the veterans left the system, "the pressure grew on university metals professors to produce artists, and the gulf between the two grew." Even today, she says, the majority of college and university metals programs focus on art and design classes, with instructors often discouraging students from careers in the jewelry industry.

That was compounded by the fact that most professional jewelry shops have traditionally been family businesses, with the owners often trained by their fathers. "They [the owners] told me, 'We don't know who these students are, they're not family, and we don't know how to get them up to speed.'"

Aalund decided to do something about both issues, and the result is A Jeweler's Guide to Apprenticeships. Although she originally thought she might write a book directed toward students, showing how they could better prepare themselves for a professional jewelry career, ultimately she decided to focus on jewelry business owners. "I realized the book really needed to show these owners how to implement effective apprenticeship programs," she says.

Although Aalund applied her own pedagogical training to the book, she also drew on her experiences as an apprentice and student— both inside and outside the classroom. Throughout her career, she has always sought to expand her knowledge by working with acknowledged masters, a practice she calls "taking on an apprenticeship mentally."

"It's that mentality of humbling yourself, and being open to learning whatever it is you need to learn," she says. However, that approach also creates a need for masters who can teach, something too often in short supply. For example, Aalund recalls the time when she traveled to Berlin to study with a jeweler who specialized in military regalia.

"Many jewelers have basic skills so deeply ingrained that they may not think to tell someone not to polish a loose chain on a buffing wheel."

— Nanz Aalund

"He was a master craftsman who did phenomenal regalia, but he couldn't break it down into steps to teach me how to do it," she says. "He'd say, 'Watch what I'm doing' and very quickly make something, then he'd hand me the materials and say, 'OK, make it.' That's why I added the step-by-step projects into the guide, as well as the safety information: Many jewelers have basic skills so deeply ingrained that they may not think to tell someone not to polish a loose chain on a buffing wheel, that it could easily get caught and lacerate their hands. It's like stating the obvious."

A Jeweler's Guide to Apprenticeships is being published as part of the MJSA BEaJEWELER outreach initiative, which seeks to both help schools promote their jewelry-related programs and provide pathways toward professional careers. The program is funded in part through a grant from the JCK Industry Fund. The book can be ordered through MJSA for $29.50 ($25 for MJSA members). For more information, go to the "Career Resources" section of MJSA.org or call 1-800-444-MJSA

(6572). **

The award-winning Journal is published monthly by MJSA, the trade association for professional jewelry makers, designers, and related suppliers. It offers design ideas, fabrication and production techniques, bench tips, business and marketing insights, and trend and technology updates—the information crucial for business success. “More than other publications, MJSA Journal is oriented toward people like me: those trying to earn a living by designing and making jewelry,” says Jim Binnion of James Binnion Metal Arts.

Click here to read our latest articles

Click here to get a FREE four-month trial subscription.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.