Objects of Contemplation

14 Minute Read

The sculpture of Helen Mason raises many important issues in twentieth-century art: the relationship between craft and fine art, the role of materials and scale, the artist's view of her work and her place in modern society, and the function of the public in response to the artist's work. Mason's art is created in two distinct and very different sizes, that of indoor, human scale sculpture and that of small, wearable pieces of art. Since the artist creates work that crosses the traditional boundaries of fine art and craft, of nonfunctional and functional, the parameters of art are pushed and tested in her work. Distinguishing between fine art and craft is complex, and Helen Mason's small work, her jewelry, is constructed with the same physical and metaphorical properties that she gives to her large scale sculpture; thus making the distinction not one of craft/fine art, but one of scale/presence.

Mason was trained in the fine arts, first as a painter, and later as a sculptor/metalsmith. Because of this strong background she has always seen herself as a sculptor working on small scale objects, even in work that is meant to serve a function, such as jewelry. From the beginning her paintings reflected her interest in abstraction, and they were a clear indication that abstraction would be the direction her work would always follow. Raising three children and teaching necessitated a long maturation process in her artistic development and during this time Mason moved from painting to sculpture, earning a B.F.A. from Rhode Island School of Design and an M.F.A. from the University of Delaware. Her earliest three-dimensional works were direct carvings in stone but the processes of additive construction intrigued her and she began to work in clay. She quickly began to add other materials to the clay and ultimately started using mixed materials in all of her pieces, incorporating various metals as well as rubber and Teflon.

Following a 1989 exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, which included tabletop pieces and free-standing floor sculptures, the artist decided to work in a scale that allowed her to be solely and completely in control, without the help of studio assistants. This desire for independence and absolute command is not difficult to understand when viewing Mason's sculpture. Each work is self-contained, uncompromising, and singular. The most recent body of small, intimate, and wearable objects reiterates the artist's desire to be in complete charge of the creation and fabrication of her work. Now, instead of making life-size pieces, Mason uses the human body as part of the sculpture. Human scale, once obtained through free standing sculpture, is achieved when the jewelry is worn and becomes functional. Mason believes the human body acts not only as a pedestal but also as a mobile armature, and that there is a spiritual relationship between the work and the person wearing it. Furthermore, as a sculptor, she is searching for new ways to make three-dimensional forms for the body that will be an extension of the physical presence of the person adorned.

Not surprisingly, there are many of the same images and themes running through both the small and the large works. The color black continues to play an important role and many of the forms remain layered, bundled, gathered, and folded. These constructs, among others, are an extension of a theme that runs through all of the artist's oeuvre. Mason also uses materials in the smaller pieces that are the same as the media in her larger works: rubber, Teflon, anodized aluminum, and found industrial goods. Thus, not only has the artist continued her explorations of theme and content with the small works, she also continues her use of many of the same forms and media.

In regards to the traditional distinctions between the fine arts and the crafts it is virtually impossible to separate the recent body of small work from that produced earlier. In fact, the artist categorically states that she does not think in these terms and the new work is obviously connected to past bodies of work. For Helen Mason, as for many others, the distinction between functional and non-functional art no longer defines the differences between craft and fine art. Moreover, craftsmanship, the idea that technique is important, is a part of both artist's small and large pieces. The intellectual process and the physical construction of Mason's jewelry remain linked to that of her sculpture, and she thinks of her works in terms of big and small, not fine are and craft.

This lack of definition and the blurring of the lines of demarcation between fine art and craft is not unique to the work of Mason and is a distinct part of the post-modern world. But the roots of this philosophy can be traced in Mason's oeuvre to her strong foundation in Minimalism. The coolness and detachment of minimalist art, in both its forms and use of industrial materials, has been noted by many critics and scholars. The use of standard, fabricated materials unites sculpture, a "high" art form, with industrial manufacturing. This particular idea can even be traced as far back as Dada in the early twentieth century. However, the Minimalist artists combined the aesthetics of the early twentieth century. However, the Minimalist artists combined the aesthetics of a modern world: reduction, simplification, and lack of adornment, with the materials of a modern world. Within this method there is careful attention to given to balance and symmetry, and because of the reduction of forms every element in a design is of absolute importance. Similar to much Minimalist work, Mason's art is three-dimensional. Of equal importance is the fact that Mason is concerned with simplification and the reduction of forms. With the creation of every work the artist asks: "How can I take something more away?" of the artist and situated the resulting object within the territory of the impersonal and the anonymous. This characteristic also denies any quality of preciousness in the completed work.

This is not to suggest that Mason has simply appropriated Minimalist forms and ideology. She has not remained an artist trapped in the sixties, but has continually sought to experiment with new materials and new ideas. Her long-standing interest in, and association with, the arts of Japan has added a unique dimension to her work. The artist considers her desire for simplification to be connected with both Minimalism and the art and culture of Japan. She wrote: "My contact and relationship with Japanese culture has influenced me - I am constantly searching for solutions that simplify." Specifically, while Mason may borrow elements of design from Minimalist art, she also incorporates the mystery and drama of the East. The artist sees her use of the color black as both symbolic and dramatic and her interest in bundles, knots, and tubes as derived as much from the art of Japan as from the forms of the modern industrial world. With her unusual vision she understands the intertwining of art and life that is ever present in Japan and looks to promote the same kind of vision in America, through her fascination with and use of found objects and industrial forms and materials.

A confluence of East and West appears in Mason's work. She is not only intrigued by the forms of Japanese art and the very Western ideas of Minimalism, but she sees a point in space where the forms and ideologies of these two distinctly different cultural forces intersect. She wants to take Japanese forms and make them more hard edged. The simplicity and elegance found in functional objects from Japan attracts the artist at the same time that she finds inspiration in the materials of the modern industrial age. The reduction of form that is a part of the Japanese art reinforces her Western foundation in Minimalist sculpture.

There are other key aspects of Japanese art that inform Mason's work. For instance, in addition to the tubular shapes of the Samurai swords and the belts around the waists of the Sumo wrestlers, she is also fascinated by the complex textile patterns and designs that are a part of the rich, Japanese heritage. This imagery appears in her silk-screened, roller-printed, and etched metals and is more representative of the post-modern aesthetic of borrowing and homage than of Minimalism.

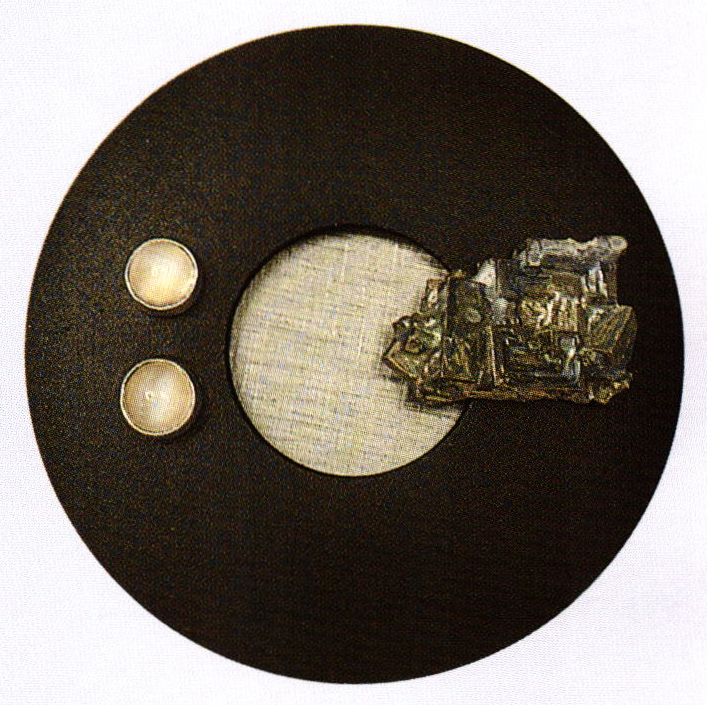

Texture and pattern are a consistent interest to the artist. In her small works Mason mixes the precious (gold, silver, and stones) with industrial materials, always searching for the means to imbue industrial materials with the same aesthetic values and rich qualities of gold and silver. Using Teflon, aluminum, rubber, and steel, in addition to precious metals, Mason layers, bundles, weaves, wraps, and knots carefully defined shapes and forms into controlled and minimal designs. Yet experimentation with new and unusual materials never interferes with her careful technical presentation. Although the quality of design is the most significant aspect of the small sculptures/jewelry, the technical virtuosity of their production, as in all of Mason's works, is impressive. Making Teflon appear rich requires many layers of color. The surface of one of the Teflon brooches, for example, is sleek and elegant, with no unnecessary details; the Teflon disc is seamlessly joined to gold, which is textured to look like an industrial material. Placed on top of the Teflon disk is a baroque stick pearl, while a natural pink pearl lays on top of the gold area. This combination of precious and non-precious materials is executed with careful attention, not only to the media, but also to the simplicity and elegance of the overall design. A typical characteristic of all of the artist's work is the reduction of form and an understanding of proportion and scale. Every detail is significant and none is superfluous. This careful and complete control of both design and materials is characteristic of the way in which the artist works to eliminate anything that would distract from the impact or power of the finished object.

Some pieces are constructed of only one material, as in the neckpiece comprised of flat and tubular rubber. Recalling the large neck ornaments of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mycenae, the pieces allude to the exquisite gold jewelry of these civilizations even though they are made of a modern industrial material. Thus not only has Mason imbued the rubber material with associations of precious materials, she also ties the work to history, while never allowing the work to loose its contemporary associations. This delicate balance of form and content is achieved through careful and specific aesthetic considerations and once again marks her connection to contemporary currents in art.

Although much of Mason's jewelry demands serious consideration, the bundled brooches of cinnamon sticks have a whimsical quality, due to both their material and the intriguing patterns silk-screened onto the anodized aluminum that encircles the bundles. Here the artist mixes industrial materials which are inorganic and hard with the sweet pungency and softness of the organic cinnamon. The patterns on the aluminum, like those in the earlier, larger works, are informed by the art of Japan. Mason's interest in bundles and groupings of organic materials can, in part, be seen as reflective of the artist's love of Japanese gardens as well as the visual arts. Japanese gardens demonstrate a concern for the interwoven spirit of art and life. It is this aspect that Mason joins to her American experience of modern materials and forms: bundles of steel tubes, cables, wires, tires, rubber, and Teflon.

Mason also attributes her interest in allegorical themes to the East. She finds, for instance, that the color black has important associations for her. She believes it to be a color of mystery and one symbolic of the night, the time when she does much of her best work. It is also a color of elegance and quiet, a color that the artist feels is calming. In its quietness it sets the stage for the drama of the design. Multiple layers of black are a recurring design element and have become closely associated with the artist, who dresses primarily in clothes of black and white.

The metaphorical elements of Mason's work clearly distinguishes it from Minimalism and connects it closely to more contemporary trends. Mason is quick to point out that her art depends not only upon formal elements but also upon content. Her attention to the relationship between wearer and object brings an element of controlled chance to the design; and this spiritual interconnectedness of object and wearer is completely unrelated to the cool detachment of pure Minimalism. Mason says, regarding the relationship between object and wearer: "It is the wearer who determines how the object should function, that when worn (the object) should be an extension of one's physical self and create an identity of its own. The nearness of the piece to the body, not its size, is the means by which jewelry can create a connection between the creator and the wearer."

There is a bond between audience and object in both the large and small works. In the large sculptures, the audience is apart from the work and must interact with the object from a distance. The nature of jewelry, however, requires a close and intimate relationship between wearer and object. Mason takes advantage of this symbiotic relationship by creating objects which are completed when they are placed upon the living armature. Yet although this last step must be taken to conclude a work, each object also function independently from the armature, and like the large scale works, is carefully designed and produced with a high level of technical achievement. Believing that design is the most significant factor, with technical process following, the artist searches for new ways to make three-dimensional forms for the body that are an extension of one's physical self.

Over the last fifteen years of her career, Helen Mason has pursued several important paths in her work, always keeping a strong focus on design while searching for innovative ways to express ideas, and always with the desire to break boundaries. Ultimately, Mason's hope is to have works of jewelry accepted and honored as independent objects of art.

J. Susan Isaacs is an art historian and critic residing in Wilmington Delaware.

NOTES

Helen Mason's large scale sculpture has been discussed in this journal before. See Betty Helen Longhi "Helen Mason: Form and Spirit," Metalsmith, Summer, 1989, page 47.

Many of Mason's ideas about her creative concepts and her materials were shared in a discussion with the author on Friday, August 21, 1992. It was during this discussion that the artist was asked not only about her aesthetic agenda, but also about her role as an artist and woman in today's society. Mason does not feel that her work is connected in its imagery to women's issues and she believes that her art is unrelated to the fact that she is female. However, she has stated that it is more difficult for women to find time to create art.

This 1989 exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum followed a twelve week sabbatical and an individual artist's grant to Japan in 1986. After extensive study and several years of work, the artist exhibited her large-scale pieces.

Mason's new work will be exhibited in 1993 at Jewelerswerk, in Washington D.C. and at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and the American Craft Museum in New York City.

This statement was included in a body of handwritten notes entitled Random Thoughts, written by the artist in August of 1992.

The relationship between craft and fine art was discussed at great length with the author in the August 21 interview.

According to Dore Ashton, the earliest cohesive expression of the Minimalist aesthetic was the exhibition Primary Structures, at the Jewish Museum in 1966. The accompanying catalog essay by Kynaston McShine recognized the detachment and anonymity achieved by the artists through their use of reduced forms and industrial materials. Kynaston McShine, Primary Structures (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1966). Dore Ashton, American Art Since 1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982):108-09.

Interview, August 21, 1992.

These ideas are contained in some handwritten notes by the artist from August, 1992 that the artist gave to the author.

Interview, August 21, 1992.

In my conversation with the artist she discussed the source and inspiration for these patterns as inspired by the patterns on Japanese textiles and metalwork seen on her several trips to Japan, including her 1992 extended visit.

Interview, August 21, 1992.

This comment is included in Mason's formal 1992 "Artist's Statement." n.p.

Mason, "Random Thoughts." n.p.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.