Off the Centerline

15 Minute Read

Off the Centerline

In every profession there are highly visible and energetic ambassadors. And then, there are those who act on a more modest level, becoming a valuable part of the profession's infrastructure. Michael Jerry is one of the latter, from the generation known as the midcentury American renaissance, who has given his life to the dissemination of a conceptual and material knowledge in the furtherance of modern metalsmithing.

Michael Jerry has been involved in metalsmithing for over 30 years. With both parents involved in the arts, in 1956 Jerry decided to seek a degree in metalsmithing. Few educational programs offered such training but, after reading an article in the Saturday Evening Post magazine, he selected the School for American Craftsmen (SAC) in Rochester, New York. Many of the teachers in the then, new crafts programs came from Europe and were interested in passing along the age-old techniques they had learned in an apprenticeship system. Hans Christensen was typical of these new instructors at SAC, barely speaking English to his students. Rather, he attempted to pass along the trade of the journeyman to this new generation of American craftsmen through rigorous technical training. Unfortunately, this meant students like Jerry had to experiment "in secret" with techniques not approved of by such traditionalist teachers.

Jerry decided to move on the Cranbrook Academy of Art to complete his Bachelor's degree. Studying under Richard Thomas and among a fine set of students, such as Brent Kington and Fred Fenster, he experienced a much wider range of techniques, design approaches and an open, positive approach to jewelry, which had been missing at SAC.

The rigorous technical training was what first drew Jerry to SAC. Its limited scope diverted him to Cranbrook. Yet to Jerry, Cranbrook's hands-off educational style was too lax, and he returned after a year-and-a-half to complete both his B.F.A. and M.F.A. degrees at SAC. His "Christensen" training was further enriched by working briefly as a production jeweler in the Rochester shops of Ronald Pearson and Ruth and Toza Radakovich.

Jerry's generation has been the historic role model for most of those who came after. Jerry and his peers experimented with little-known techniques. Some adapted old or industrial working methods and set them into small contemporary studios. Jerry was at ease with traditional techniques and fully confident of his ability to design and make holloware in the mold of Jack Prip, Christensen and Arthur Pulos. Yet, youthful exuberance and instinct provided him with a thread of unease and a restlessness with tradition that would continue throughout his career. This complex and contradictory nature is perhaps inherent to his generation, who embraced new materials, techniques and concepts. The history and design they were taught were perhaps stifling. The variety of techniques and materials becoming available through research and experimentation was without precedent. This new wave of students, now on their own, found these events stimulating, if a bit daunting.

In 1963, with an M.F.A. in hand, work experience in two respected shops and a year of teaching, Jerry set out in pursuit of his dream - a job as a designer/modelmaker for the silver industry. This line of work was considered the most respectable and had been highly touted in school. Jack Prip's position with Reed & Barton was his primary model. On a three-week trip with a promising portfolio in hand, Jerry approached every major silver company in the Northeast. He was offered a job with Reed & Barton - the oldest and largest of the group from which Jack Prip had just decided to move on.

The job description had changed, however. The job Jerry was offered was to work with a partner designing items within a strict traditional style of detailed Germanic ornament. In retrospect, Jerry believes he was steered in this direction because he was fairly young, and Reed & Barton probably did not think they could replace Prip. Jerry could not see spending many years designing within that style, and so, with regret, he turned the job down.

The flip side of this decision, however, was that Jerry became a teacher. Upon his return to Rochester, a call came From a school in Wisconsin that needed a design teacher immediately. With personal responsibilities to consider, Jerry jumped at the opportunity. He taught three-dimensional design at Wisconsin State University, Stout (in Menomonie), for the next three years. He worked with the school to develop a metals area in the growing art department and headed this new metals department for the next four years. Feeling restless in the relatively small Midwest town, he was eager to move on. When he left, he was a tenured associate professor, had built a department and had served as a temporary head of the art department, important accomplishments in seven years.

The confidence he had in his ability to design and create both holloware and jewelry had been confirmed by his already respectable exhibition record. While at Cranbrook he was accepted into one of the early modern jewelry exhibitions, the important 1959 exhibition of American jewelry at the Walker Art Center. This third show in that series was published in a double issue of Design Quarterly. This exhibition was regarded as the tip-off on what 1960s jewelry was going to be like. And, although he was only two years out of school, his work was being toured in eight European countries in a USIA sponsored exhibition called "Fiber, Clay, Metal." He was selected for several of the early exhibitions mounted at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, including "Objects USA." Internationally, Jerry was in several German exhibitions titled "Form and Quality," a part of the International Trade Fair in Munich.

Jerry has always worked in both jewelry and holloware. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, his jewelry was cast. The earliest work was carved, highly textural, organic form. It was positioned somewhere between the styles of Toza and Ruth Radakovich and that of Olaf Skoogfors. The work was progressively pared down to a smooth, refined, stylized surface, angular but for the necessary curves of function. Stones remained a common factor throughout, moving from cabochon and pearls to faceted gemstones. Jerry remembers doing a lot of liturgical holloware commissions in the 1960s, recalling how difficult it was designing for group consensus.

Michael Jerry was a founding member of The Society of North American Goldsmiths. At the first conference in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, he met John Marshall, among others, and the two began corresponding. As Marshall was planning a sabbatical leave from Syracuse University's metals department, he invited Jerry to replace him, and upon his return, to share the department. This offer was very welcome. "I wanted a larger school and more sophisticated students. . ." After accepting the offer, Jerry learned that Marshall was resigning, apparently due to school politics, which left him as head of the department that John Marshall had built. He has now taught there for 21 years.

On the way to teach at Syracuse, Jerry attended a special workshop on blacksmithing put on in "the middle of the woods." In the spring of 1970, Brent Kington organized a workshop at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale with AIex Bealer, historian and author of The Art of Blacksmithing. It was attended by Bob Ebendorf, Fred Fenster, Fred Woell, Stanley Lechtzin, Ron Pearson and others who had never worked in iron before. There was great excitement at being able to generate metalwork so quickly. Work, following the nature of the material, was linear and rambling, split and curled. It was fast and strong, physical and demanding. This "spontaneity" was powerful stuff.

The excitement generated at the workshop changed Jerry's work. He proceeded to set up a blacksmith shop as soon as he arrived at Syracuse, and blacksmithing was offered during the summers for a number of years. For nearly a decade, his own work concentrated on iron in combination with other metals. One piece, typical of his ironwork, is a cooking pot, now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jewelry during this period became as detailed as the ironwork was free-flowing, This continued a pattern of balance in Jerry's approach, whereby iron allowed some relaxation of rigor while jewelry required complex technique. Neckpieces, for example, were hollow-formed and multi-jointed to follow the body's form. The design style related to the forms produced in iron, yet the technique was confined, highly controlled and precise, requiring much preplanning.

Several years later, Jerry invited friend and colleague Fred Fenster to do a workshop on pewter. As he sat there with the students, he found himself mesmerized as Fenster "magically produced his forms." Jerry began exploring pewter's possibilities. He set up a work space for the new material at his own studio as well as the school's shop. His own work changed dramatically, once again.

Pewter reminded him of his early materials, especially in holloware. The realm of the functional form returned. This new direction brought back the uneasy memories of the fully rational, coherent design requirements of the Scandinavian Modern style of his student days. Pewter did not have the reputation of silver, where seriousness, competence and status compelled a smith to create more formally. Full drawings and workups could give way to sketches and vagueness. A vessel could begin going in one direction and a mid-course evaluation could alter it entirely. This was freedom; this was spontaneity, and it carried a responsibility of its own. It was, however, consistent with Jerry's nagging rebellion against strict training.

Some of Jerry's best works of this time were asymmetrical, flowing goblets. Thick lipped and sensuous, they seemed to speak for their time, the early 1970s, a time when everything, from fashion to literature, seemed funky, fat and awkward. The linear meanderings of ironwork gave way to a more refined, understated surface line that accentuated the form. On some, the line was highlighted with a stone. He was amazed that these "new" forms could be completed in just three or four days, where in silver they might take weeks, if undertaken at all. The material allowed for the unforgivable: running out of material. A piece could be spliced in, pounded down and the form completed without much of a visible seam, if any. On the other hand, its stability, welding temperatures and so forth, provided for perils of a new variety. Yet, these were perils Jerry has enjoyed working with for over 10 years now.

Jerry's penchant for change in style and materials has been partially due to personal restlessness, exacerbated by what he calls "interruptions," a term he uses for work that is distinctly "out of sync" or "off the centerline" of his current thought. It stems from an overwhelming desire to make items he knows he shouldn't. These sudden, impulsive objects are uncomfortable to him, as if he somehow ended up with them but isn't sure where they came from or where they belong.

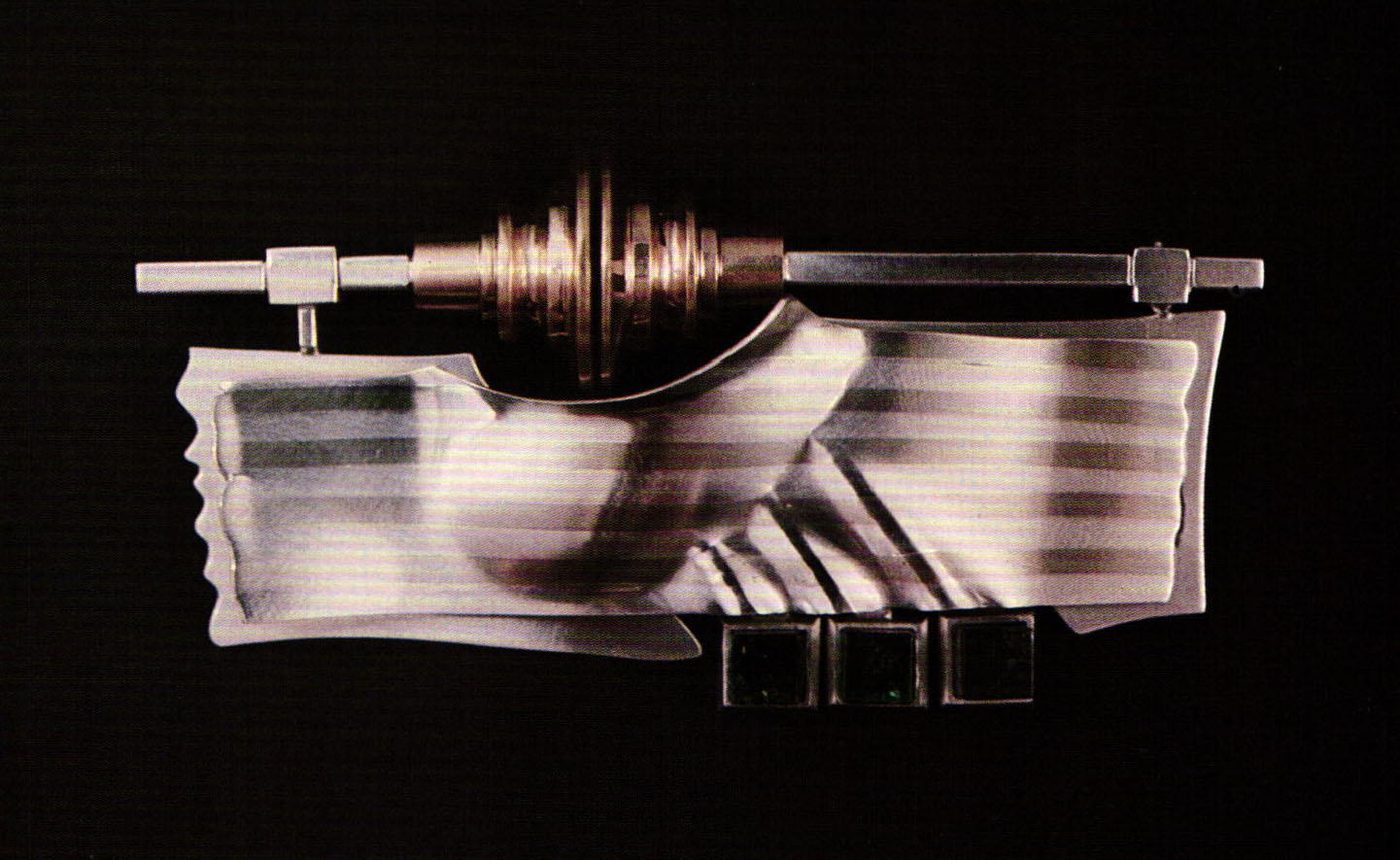

As a student, Jerry found himself given to these impulses. He once had a desire to make spouts he knew would not work and place them on containers he knew would not be proper, from a functional point of view. Jerry still has many of these spouts and makes good use of them as classroom examples. Recently, Jerry's "interruptions" have helped lead him to personal design styles that reinvigorate and change his main work. As in the earliest years, they have by and large spoken for his times. The instinctive playfulness that challenges his current esthetic has become his trademark working style. Pieces and parts that do not meet his criteria are set aside. These "planned" parts will be called upon later for jewelry, in an unplanned arrangement of the moment. He views his jewelry these days as "byproducts or recycled items." He tends to make them when time does not allow him to embark upon the more intensive holloware pieces.

These "interruptions" also relate to his role as teacher. Jerry's living has been made through teaching. That tends to relegate artmaking to "spare" time and intensive summer work periods. Furthermore, if you are successful and have been teaching 20 or 30 years, as Jerry has, responsibilities such as heading the art department are added from time to time. Michael Jerry has experienced many such interruptions over his career. However, one type of interruption that Jerry feels has been beneficial to his art has been working with art programs held abroad. The largest such post was as the director of Syracuse University's London Art Program for a year-and-a-half in the 1970s. Another time he taught in an art program in Florence, Italy. Jerry counts these international experiences among his most influential. He visited many museums and galleries. The European style of life has been recorded in his journals. Sketches of architectural derails were especially important, as architectural elements began appearing in his work. More than detail, they evoke a sense of place, of street and building environment in the European style. These influences have played out in some of his pewter teapots of the past few years.

Facility with the bandsaw and sander have helped give shape to these ideas. Working in a modest metalsmith's studio for so many years, Jerry recently decided to purchase these tools to be able to explore new forms more rapidly. One of the elements that emerged from these tools was a variation on wood crown moldings (which make the transition from a wall to a ceiling). Jerry plays with sculptural shapes and surface patterns, both subtractive and additive, as well as inlay. These works began under the guise of one of his "interruptions."

Eventually, these spontaneous works began to suggest vessels again. A handle developed, a spout, even intricate lid mechanisms. He has enjoyed inventing and problem-solving, which combine the need for structural support and visual detail. An example is splicing copper between pewter walls and exposing the edge. Yet, as soon as these forms became vessels, they had a responsibility to be functional, although the extent to which they lean and tilt uncomfortably might not lead to such a perception. But Jerry finds this slight helter-skelter quality quite challenging and even comfortable. Perhaps they reflect today. At this point Jerry's teapots could not be further away from strict vessels and liturgical pieces of his early days in metal.

The artwork Jerry has been involved with over the past decade has been more for self-nourishment than public exhibition and exposure. He has enjoyed his teaching career, but has deliberately kept his work out of the metals department. As a reaction to the way he was taught, he feels, "l don't want to burden them with [my work]." As he sees it, "My vision is mine. They are mature individuals fully capable of expressing themselves." Jerry is pleased that his department is set in a university where the students' education is broadened beyond technique. As Jerry and his work have matured over three decades, it is clear that where he was once influenced by the excitement and challenge of material, technique and momentum, he has increasingly responded to his own personal rhythm. His work is singular, even isolated. The jerrybuilt paper, cardboard, styrofoam and wood of his design blocks are the event, a private performance for an audience of one. This is a humble approach from a humble man. His work continues to emanate from high artistic principles and sophistication of style and technique. Jerry's working and teaching careers hold value for, and are an example to, contemporary metalsmithing.

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer living near Rochester, NY.

Notes

(All personal information and quotes not cited are from taped interviews between Michael Jerry and William Baran-Mickle on 3/26/91 and 4/8/91.)

See Robert Cardinale and Lita S. Bratt, Copper II, Second Copper, Brass and Bronze Exhibition, University of Arizona Museum of Art, 1980, pp. 6-7. The authors present the concept of pseudogenerations within the American renaissance of metalsmithing at midcentury. Among those selected as the first group, already established and influential: Christensen, Thomas, Skoogfors, Eikerman, Prip and Fike. The second group: Kington, Fenster, Seppä, Lechtzin, Scherr, Fisch, Pearson. The third group: Paley, Ebendorf, Pijanowskis, Woell, Moty, Hu, Mawdsley and Harper. Jerry would belong in the second group.

Jerry said of SAC, "commitment to the medium was immediate, which is what I wanted."

Cranbrook accepted undergraduates as well as graduates at the time. Jerry was responsible for making the ladle in Thomas's 1960 book, Metalsmithing.

Prip began working for Reed & Barton in 1957. In 1960 he resigned that full-time post but remained a design consultant until 1970. In 1963 he began teaching at Rhode Island School of Design. See: John Prip Master Metalsmith, exhibition catalog, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design and American Craft Museum, 1987.

Design Quarterly #45-46, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1959. Page 24 is devoted to Jerry and contains five photographs of five works.

See: Philip Morton, Contemporary Jewelry, 1 st edition, 1970. Three exhibits were held at the Walker, in 1948, 1955 and 1959. These were outgrowths of the 1946 Museum of Modern Art (New York) exhibition on modern jewelry. Morton discusses the importance of these shows in terms of stimulating the growth of contemporary jewelry in America. Discussion, pp. 36-39; listing of selected artists and photos, pp. 271-282, including Jerry.

The two early shows at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts were "Emergence" and "Craftsmen '66" in 1963 and 1966, respectively. The Museum opened in 1956. The "Objects USA" exhibition was The Johnson Collection of Contemporary Crafts and was exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution's National Collection of Fine Arts in 1969. It later became, and remains, the major portion of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts permanent collection.

Taped interview between Michael Jerry and Sarah Bodine and Michael Dunas, 4/8/87.

See "Blacksmithing Wins Place in University Courses," Christian Science Monitor, 10/74. See also Goldsmith's Journal, v. 5, n. 6, p. 14, for mention and photograph of the work accepted into the collection of the Metropolitan. Two such prominent exhibitions of ironwork in which Jerry participated were: "the Hand Wrought Object 1776-1976" at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, and "Iron solid Wrought USA" at University Museum, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and Museum of Contemporary Crafts, NYC (1976).

Bodine/Dunas interview, 1987.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.