The Perfect Paradox

15 Minute Read

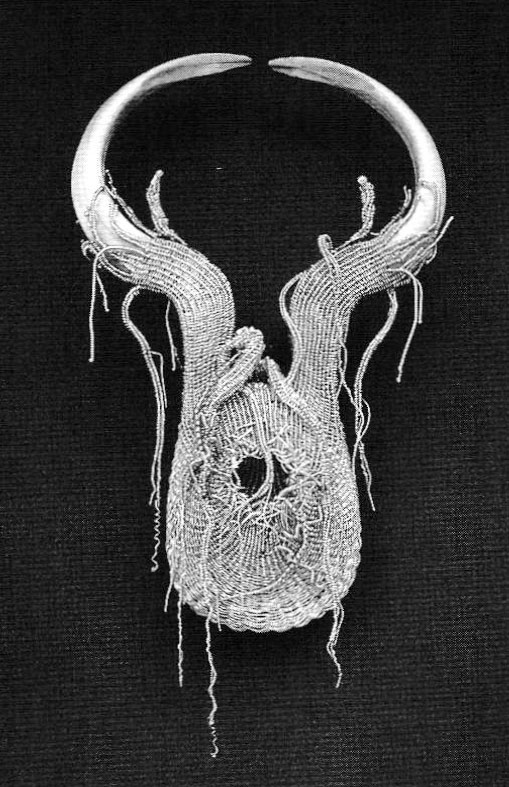

Tone Vigeland's oeuvre is contradiction objectified. Her jewelry is a visual discourse between opposites: large-small, hard-soft, rigid-fluid, tight-loose, inertia-movement, stricture-freedom, compulsion-relaxation. Each piece is a scrupulous amalgam of scale, structure, symmetry, surface, sensuality, and meticulous craftsmanship. She believes her jewelry to be complete only when it interacts with the human body, conforming to its contours and altering in harmony with its movements. And although comfort is a priority, her pieces, nonetheless, often verge on the ceremonial.

Norwegian by birth and residence, Vigeland has absorbed the spirit of a land which produced artistic wonders as diverse as the complex interlacing of ancient Viking metalwork, the moody expressionism of Edvard Munch's paintings, and the technical prowess of Gret Prytz Kittelsen's enamels. Yet, Vigeland has emerged as a maverick, not only at home, but even amongst the international jewelry avant-garde. She belongs to no movement and subscribes to no ideology.

Unit construction forms the basis from which her jewelry emanates, the foundation upon which it is built. And although several other contemporary jewelers, such as Patricia Meyerowitz, Betty Cooke, and Robert Smit often utilize identical, repetitive elements as the components of their necklaces, bracelets, brooches, and earrings, Vigeland opts for increased complexity through textural and kinetic considerations, specifically the tactile and dynamic dimensions possible through the addition of tiny surface attachments. All-in-all, these intricate mini-structural systems are the result of a painstaking evolution which has its roots in the mid-twentieth century and the then prevailing canon of Scandinavian modern design. As David Revere McFadden wrote: "During the 1950s, the style [Scandinavian Design] attracted an almost unprecedented following of critics and consumers. The primary virtue ascribed to Scandinavian objects was an overall design excellence, aesthetically and functionally."

Tone Vigeland was born on August 6, 1938, into a stellar artistic family. Her grandfather Emanuel was a prominent stained glass artist and fresco painter, great-uncle Gustav a famous sculptor, and father Per the creator of large-scale ecclesiastical decorations in stained glass and mosaic tile. Vigeland completed her required education in 1955, after which she attended Statens Håndverks-og Kunstindustriskole (National College of Arts, Crafts, and Design) to study metalsmithing. She had also briefly considered ceramics but ultimately chose metals because of the technical immediacy inherent in forging, piercing, and soldering, etceteras. While there, she took design with Oscar Sørensen and goldsmithing with Sigard Alf Ericksen. In 1957, she applied to Oslo Yrkeskole (The Oslo Vocational School). This four year technical training course in jewelry was mandatory in order to qualify for a journeyman's degree, required for teaching, buying, selling, and even working gold and silver.

While attending the Oslo Yrkeskole, Vigeland made a pair of screwless silver earrings, based upon earlier experiments in copper and pewter, and inspired by a summer visit to Denmark in 1953 when she was fifteen years of age. At that time, the gracefully undulant jewelry by Henning Koppel figured prominently in the repertory of the venerable Danish firm of Georg Jensen. And the curvaceous necklaces and bracelets by Swedish jeweler Torun Bülow-Hübe (who was to design for Georg Jensen, also, beginning in 1967) had already been exhibited in Norway in 1951. These earrings, by Vigeland, entitled Sling, resemble an open numeral 6; the long top-tail nestles behind the ear while the lower scroll curves inward to hook into the lobe, a brilliant design which eliminates the need for the clumsy appendages usually necessary for wear. Per Tannum, manager of Norway Designs, saw the earrings at a student exhibition and invited Vigeland to apprentice at Plus, an arts and crafts center in Fredrikstad which he founded in 1958, with the purpose of commissioning artists to create original designs for industrial production; needless to say, unpretentious prototypes in silver, clay, fiber, etceteras were meant to elevate commercial standards through aesthetic and technical excellence.

Vigeland worked in the Plus silver workshops, under the direction of Erling Christoffersen, from 1958-61, at which time she received her goldsmith's certificate and started an independent studio in Fredrikstad while continuing to design for Plus on a freelance basis. During these nascent years, she created jewelry stylistically consistent with the rubric of Scandinavian modern jewelry design: clean lines, simple silhouettes, unadorned surfaces, restricted ornamentation, visible technical solutions, and gentle spirals and curves forged to mimic the contours of the human body. To wit, serpentine bracelets coiled around the wrist and tortuous necklaces embraced the throat in a gestural sweep reminiscent of Torun, whom Vigeland gratefully acknowledges. However, although clearly inspired, in her embryonic years, by the Swedish jeweler's body-consciousness, Vigeland diverged significantly as regards symmetry. Whereas Torun emphasized the winding curve, often at the expense of equipoise, balance is of the utmost importance to Vigeland, and, in certain respects, her jewelry may be perceived as an artistic manifestation of the harmony found in nature.

Nordic jewelry had been enthusiastically received by the international design community when it was exhibited at the Milan Triennale in 1957. In Norway, Vigeland was highly regarded by the press as a jeweler for the modern woman and was consequently invited to participate in the Milan Triennale of 1960. Graham Hughes, the prominent British jewelry historian, included Vigeland in the First International Survey of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961, a landmark exhibition presented at Goldsmiths' Hall in London in 1962, a year which turned out to be a watershed, in several respects, for her. While continuing to create jewelry for Plus, as well as independent works, Vigeland won first prize in the Gullsmedforbund (Association of Norwegian Goldsmiths) competition. Also that year, she represented Norway at an exhibition in Tel Aviv and was sent by Plus to Carson Pirie Scott, a Chicago department store, to demonstrate enameling in conjunction with the promotional presentation Spotlight on Scandinavia. Most importantly, it was around this time that Vigeland began to shift her emphasis. She was feeling restricted by the confining aspects of industrial design, as well as by the general craft ethic, of the time, which regarded a handmade article as not much more than simply an honest object. She wished to create more meaningful works. As she recently stated: "… crafts are more limited in their ability to convey inspiration. It is as if thoughts are … frozen within the craft object, while in the fine arts, energies within the work create references, emotions, and thoughts that evolve on a much deeper level and move away from the actual object."

In 1965, Vigeland became the youngest recipient ever awarded the prestigious Jacob Prize from the Landsforengingen Norsk Brukskunst (National Association of Norwegian Applied Arts), and in 1967, another pivotal year for her, she had first solo exhibition at the Kunstnerns (Artists' House) Oslo, an arena formerly available only to painters and sculptors. In analyzing the jewelry shown there, significant theoretical shifts became apparent. Although some of the jewelry was still clearly influenced by Torun, much displayed a good deal of color, due to the presence of stones and enamel - even the technically-demanding plique-à-jour. However, the most innovative pieces were three optically-challenging openwork medallions, each created from two circles of silver sheet, pierced in repetitive linear patterns and then placed in overlapping juxtaposition to one another and, even more momentously, a set, comprised of a combination necklace/earrings and hand piece. This suite, now disassembled, was fabricated from small gold wire rings, linked together to form a kind of mesh with pearls, and amethysts. Clearly, Vigeland was referencing East Indian jewelry, a style which had always captivated her, and was thereafter to inform her entire body of work. Marking a clean break with her prior focus, Vigeland now sought flexibility. From early in the 1970s, she was to concentrate on pieces that draped on the body.

Consistent with the general defection from machine production and a concurrent desire for new expression in the applied arts, Norway began to embrace certain styles, from around the world, which were clearly on the cutting-edge. Among other trends, the 1970s heralded a revival of the grand scale and organic curves seen in Art Nouveau. In the United States, this fashion was exemplified by Albert Paley's jewelry. In another vein, Norwegian goldsmith Christian Gaudernack returned home, in 1971, after studying with the masters in Pforzheim, Germany. He brought with him progressive ideas concerning the application of acrylics, iron, tin, and steel to jewelry. Furthermore, Gaudernack admonished Vigeland to pay more attention to surface, a notion which would henceforth go hand-in-hand with her research into the nature of pliancy.

At this time, the Netherlands, as well, was undergoing a good deal of turbulence in its jewelry community. Another novel and exceedingly influential ideology was germinating there, which ran completely counter to Vigeland's emphasis on fluidity. This was epitomized by the industrially-inspired, massively rigid body sculptures, collars, and face pieces by Gijs Bakker and Emmy Van Leersum. Their jewelry was "… intimidating, refusing to become integrated with the wearer." Vigeland believed, on the contrary, that jewelry should be comfortable; function, remember, being one of the benchmarks of modern Scandinavian design.

Simultaneously, in the United States, however, a like-minded contingent of jewelers were actively engaged in methods which were sympathetic to Vigeland's mode. Arline Fisch and Mary Lee Hu, for example, were exploring the application of textile techniques to metal wire. Still, neither knitting, crocheting, plaiting, nor braiding afforded the structural mobility which Vigeland required. Therefore, in 1973, she embarked upon her first significant experiments into the nature of flexibility: pliable bracelets and necklaces constructed from silver hemispheres threaded on a chain. These endeavors led to larger pieces, assembled from chains of small tubular silver bits, varied occasionally by the addition of enamel, stones, gold, and gold and silver in combination. Vigeland also returned attentively to studying the intricate wire joinery practiced by East Indian jewelers, a technique she alluded to previously, in 1967.

Vigeland began this journey of discovery by connecting small silver rings to create various types of mesh which recalled both chain mail and lace work. The first pieces made by this technique were large collar-like necklaces of oxidized silver, in which the mesh was given varied structures and colors. Gradually, the surface became more complex, richer, and diversified in both texture and hue. This was achieved by concealing the web-like background, in part, behind anchored elements of silver, gold, enamel, and stones.

The first in a series of important one-person exhibitions at the Kunstnerforbundet (Artists' Association) in Oslo occurred in 1978. Emboldened by continued national recognition, in 1979 Vigeland showed her work to Barbara Cartlidge, whose Electrum gallery in London specialized in jewelry by an international array of prominent artists. Cartlidge gave Vigeland a solo exhibition in 1981. Desiring to create something totally new for this show, Vigeland began playing with hand-forged nails, from an Empire-style house, which a friend had given to her. She had always been enamored of found objects and proceeded to test the boundaries of these nails; she cleaned, hammered, stretched, bent, gold-inlayed, and polished them. This led her to experiment with other types of tacks, especially the blue-black steel sorts, which when forged acquire a distinctive sheen and flat feather-like shapes. The necklaces assembled with these nails, redolent of Brazilian natural feather collars, also serve to illustrate Vigeland's fascination with a kind of romantic primitivism, consistent with much jewelry done in the 1970s. One need only view jewelry from this period by Arline Fisch, Mary Lee Hu, and Robert Lee Morris, to name a few, to recognize the impact of this tribal sensibility.

More than solely a kindred spirit, Robert Lee Morris was to play a significant role in introducing Vigeland to the American public. She met him, along with Helen W. Drutt English, owner of Helen Drutt Gallery in Philadelphia, in 1981, when she visited New York to meet with David Revere McFadden, then curator of decorative art at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. He was organizing the exhibition, Scandinavian Modern Design 1880-1980, a show which was to include pieces by Vigeland. In 1983, Morris gave Vigeland her first solo exhibition in the United States, at his jewelry gallery, Artwear.

By 1986, Vigeland was moving away from steel as her metal of choice; silver became preferred because, due to its mutability, it allows for subtle color variations not possible with steel or iron. Furthermore, silver can be controlled - chemically oxidized to different shades of gray and brown, and it also benefits from the natural patina acquired through use. At this juncture, Vigeland was utilizing silver mesh, like a stocking, as a background upon which she attached tiny silver balls in deposits of varying density. Additionally, since shading is of such consequence to her, Vigeland would regulate the amount of reflected light through selective buffing. In tandem with these processes, Vigeland relinquished, as often as was possible, cumbersome fastening apparatuses, thereby creating necklaces, belts, and bracelets which simply twist snake-like around the throat, waist, or wrist, then tuck or tie in place. That same year, she had a one-person exhibition at the Kunstindustrimuseet (Museum of Applied Arts) in Oslo and won second prize in a major jewelry exhibition in Tokyo: The Sixth Tokyo Triennial. In 1987, she was awarded the Oslo City Artist's Prize and in 1988 the Swedish Prince Eugen Medal.

As was her custom, Vigeland wished to do something untried and unique for a solo exhibition, planned for 1989, at the Kunstnerforbundet. The richly appliquéed silver mesh was abandoned in favor of flat or layered constructions composed of contiguous or overlapping silver squares or rectangles, affixed to each other by tiny, invisible rings. The overall effect may suggest a tiled floor, a shingled roof, or possibly the protective shell of an armadillo. And although Vigeland was to briefly back away from this direction, she would ultimately return to it, albeit in a different format; and it furthermore becomes apparent that these geometric works suggested to her the meshless pieces from 1991 and 1992.

During those years, she fabricated necklaces, bracelets, and caps which utilized minute squares or rectangles as surface elements but did not use the mesh stocking as a core. Instead, through an intricate mathematical procedure, she invented a unified formal apparatus consisting of identical hard-edge but mobile bits on a stiff, segmented background. Nevertheless, at the time of her solo exhibition at the Kunstnerforbundet in 1993, Vigeland, at least in certain pieces, temporarily returned to surfaces covered completely with a course, even nap - a carpet, really, of tiny seeds or motile granulation.

However, Vigeland's most recent jewelry has reverted to the idiom displayed by the flat, modular pieces from around 1989, as well as the hard-edge kinetic works done in 1991 and 1992. What she learned about engineering, at that time, directed her to invent a linking system which allows for the parallel stacking of wire-strung silver plate shapes. Hollowed out for lightness, when these squares and rectangles are set on edge and packed tightly together, their borders generate yet another brand of surface - one that is based upon linear properties. This series, in fact, serves to resolve Vigeland's colloquy between structure and surface. As Donna Gustafon wrote: "… these new pieces literally invert the structure of the earlier work so that the metal plates that once served as surface are now both structure and surface."

On the occasion of Tone Vigeland's retrospective, organized jointly by the Kunstindustimuseet and The American Federation of Arts, one naturally reevaluates her contribution to modern jewelry. Certainly, she has garnered critical acclaim, as well as institutional acceptance; her work is represented in many public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and The Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution, both in New York, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Musée des Art Décoratifs in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. But where is her place in the history of jewelry? Although critics have habitually found a facile reference to Viking armor in Vigeland's work, both this writer and the artist (although admittedly flattered) find that comparison overly simplistic. True, her use of fixed pod-like spheres may suggest Viking granulation, and any allusion to chain mail will evoke associations with battle array form the Middle Ages. But art is concerned with intent, and Vigeland's purpose diverges radically from being simply a reverent interpretation of medieval costume. Her efforts have produced so much more relevant results. In forty years, she has achieved an oeuvre which is nothing less than a subtle but sublime symbiosis of form, content, materials, process, environment, and function. She is, in fact, far closer to eastern than western philosophy. Her procedure is imbued with the slow, ritual manipulation of infinitesimally replicated parts, combined to create a whole entity. Her connection with nature is manifest in the inspiration derived from "an open landscape, the sea, the mountains, the endless white of winter … the first snow and the gray rocks on the shoreline", as well as the gradual nuances in color caused by exposure to the elements.

Tone Vigeland's jewelry is peaceful, yet it is also a battle of opposites; it is gentle but simultaneously absorbs the tensions arising out of dichotomy; it is a visual metaphor for life itself; it is the perfect paradox.

Toni Greenbaum is a writer currently residing in New York, NY.

NOTES

David Revere McFadden, "Scandinavian Modern: A Century in Profile", in Scandinavian Modern Design 1880-1980 (exh. cat. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), 12.

Tone Vigeland, interview by Donna Gustafson, October 26-27, 1994, in The Jewelry of Tone Vigeland, 1958-1995 (Oslo: Oslo Museum of Applied Art, 1995), 10.

Gert Staal, Gijs Bakker, vormgever, Solo voor een solist s-Gravenhage, SDU uitgeverij, 1989, 19.

Donna Gustafson, "Tone Vigeland, A Physical Pleasure", Ornament 19 (Winter 1995): 45.

Gustafson interview, 14.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.