Pierre Degen Plays: His Own Rules

12 Minute Read

"There are no rules there. At one point there will be an idea…and I will find a material that is suitable to express that idea. In some other cases, I will pick a piece of material and think 'Oh, that's nice piece of material, that's a nice piece of rubber, or a nice piece of card and I will play with it and eventually make it into a piece….But there are no rules….The same in the way of making. If I'm going to bash something together with two nails and a piece of wood and a bit of cellotape if necessary or if I have to spend three weeks putting something together very accurately going to work on machinery and with a milling machine very precisely, I will do it if I feel it will be necessary for the piece. There's absolutely no hard line."

It is that free-wheeling approach to materials and process that has led the now London-based Degen to create some of the most innovative jewelry of the time. He has challenged the concept of jewelry as precious by using materials as diverse as perspex, computer chips, tin cans, wine corks, and even incorporating the shadows of his pieces as a part of the visual experience. He has transcended his own traditional training as he freely admits he quite likes "if it can be done easily, even if someone else can do it quite easily". If a tin can of one of his bracelets rusts, it can be easily replaced by the owner, he notes. He has questioned scale saying, "We are used to seeing people wearing jewelry, why not jewelry wearing people?" as he has made giant propellers to be worn on the back or ladders to be carried. Quite simply for Degen, there are no rules.

A similar, almost serendipitously natural progression has marked the life of Degen, who was born in La Neuveville, Switzerland, in 1947. He did not start out to be a jeweler; he intended to become an architectural model maker. But as there were no schools, a model maker encouraged him to study something that required him to be adept with his hands, to work finely and accurately - jewelry. Degen enrolled at the Ecole d'Arts Appliqués in La Chaud-de-Fond, Switzerland, and fell in love with the craft. The program was divided into learning all the traditional jewelry techniques and drawing classes. There was no integration of the courses as he learned to set stones, studied art history, (but not the history of jewelry) and drew in composition or technical drawing classes, or from plaster casts and the landscape. There was no awareness of what was happening with contemporary jewelry as the school was geared to meet the demands of the trade.

When Degen graduated in 1968, he took a job as a designer at Bucherer in Lucerne, which he describes as a "high street jewelry shop" that required "very mundane and very run-of-the mill jewelry". At the same time he was taking drawing classes at the Kunstgewerbe Schule. After three years, Degen decided that he "wanted to travel around the world and I thought that knowing a bit of English would help". He went to London with the idea of staying six months or a year before setting off on his world travels, but a series of lucky circumstances led him to settle there permanently. At a jewelry shop in Bond Street, London's equivalent of Fifth Avenue, he met Peter Lyon who was teaching jewelry at the Central School of Art and Design in London. Lyon invited the young Swiss designer to visit the school and when he did, he met the head of the department who promptly offered him a job as the studio technician. Putting off his travels for a paying job, Degen eagerly accepted. He met Catherine Mannheim at a student-and-faculty exhibition and casually asked her if she knew of any available teaching positions. She let him know when she decided to leave her post at the Middlesex Polytechnic and in 1973 he became a part-time lecturer there, an association that continues to the present.

The one quality that could be said to characterize all of Degen's work is curiosity. Around the time he graduated from the Ecole d'Arts Appliqués, he saw a book of German jewelers that included the work of Claus Bury. Degen was very impressed with Bury's seminal work combining acrylic and gold and he immediately bought some "perspex and started to make some pieces with it. From there on, it didn't stop". Degen became interested in non-precious materials and excited by the possibility of working with them with as much refinement as he had with gold and silver. Christopher Reid in Crafts magazine, described the resulting pieces from the early '70s as being "in a recognizably Continental idiom: fat pieces of perspex, plain or colored, were shaped, perforated, engraved, superimposed, and generally arranged with care for meticulous finish". Degen added an element of visual complication with the use of mirrored surfaces and cylindrical acrylic rods through which parallel lines were viewed creating a kinetic effect. Reid saw "this penchant for optical trickery" as "a sign of dissatisfaction with the flat, cool look". These works were followed in 1972 with a playful series suggested by Ralph Turner, partner and director of the influential London gallery Electrum. He persuaded Degen to do a series of throw-away jewelry in acrylic foil, which freed Degen to embark on works made of collaged parts, all decidedly non-precious: aerosol can nozzles, curtain-runners, plastic clothes pins, plastic clothes' tags, right-angle plastic tubes used for washing machine plumbing, and electronic components. This recycling of materials has reappeared in Degen's work of the last few years as he has made bracelets from tin cans, brooches from champagne corks and rubber bands, and kinetic toys from salvaged metal.

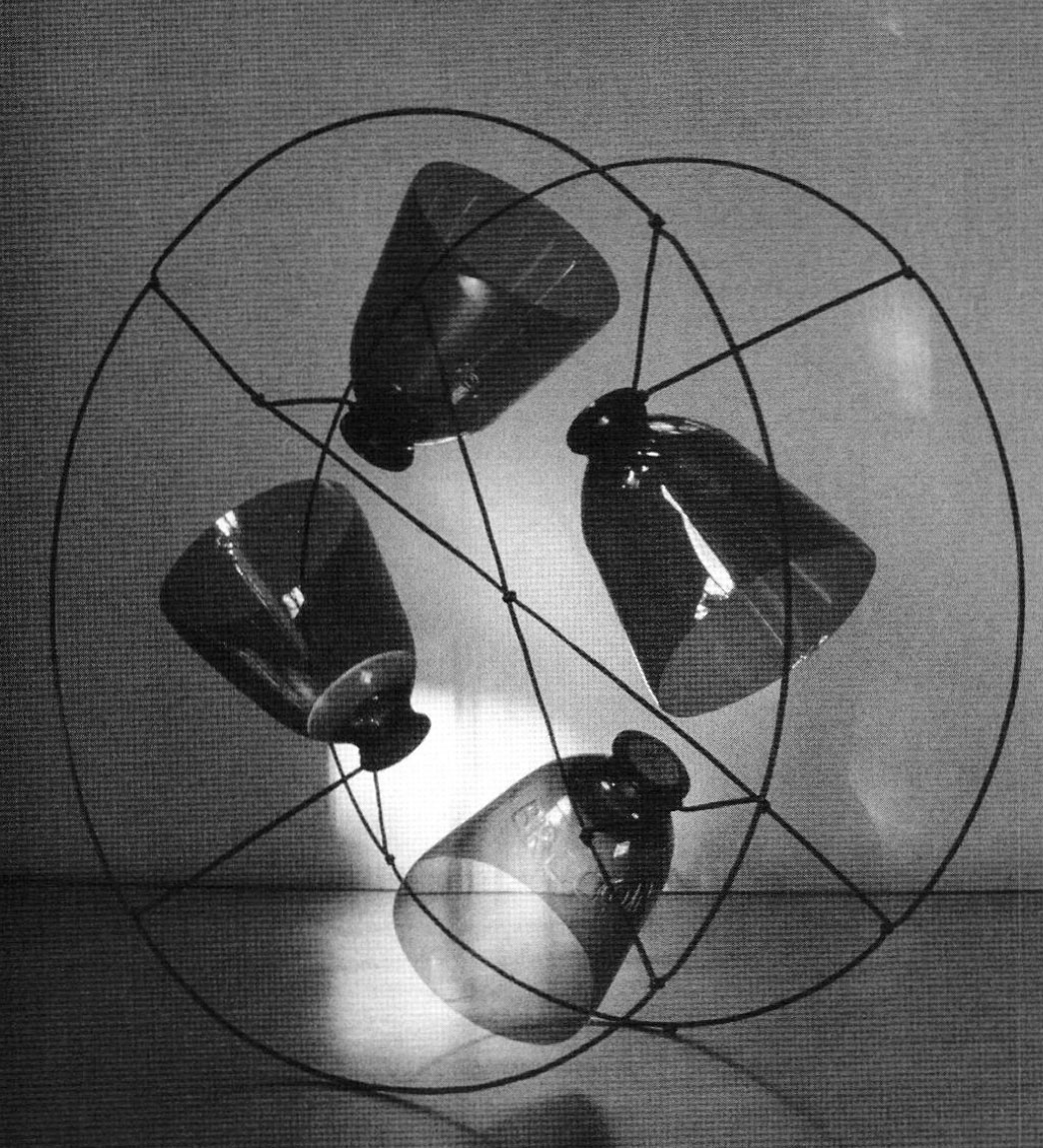

By the late 1970s, Degen had become interested in the three-dimensional quality of the assemblaged pieces and the shadows which they cast. The shadows became an integral part of the pieces and he began a series of shadow pieces or Extensions as he has called them. Made of steel rod and thin cord, in strong light they were nearly indistinguishable from their cast shadows. Reid has noted that their most radical quality was "self-effacement: for the first time we are presented with jewelry that, so far from drawing attention to itself, seeks to hide amongst ambiguities and shadow play".

The collaged works came from physically working with the components until they were "right". The shadow works began with a tight sketch that Degen would then replicate in thin wire but he found them " . . . a bit forced. Instead of doing a sketch and trying to imitate the sketch in the material, why not sketch directly with the material?…In a way it was the beginning of working far more spontaneously, which I haven't really stopped."

As the vitality of the shadow pieces was dependent upon the wearer moving to change the angle of the shadow, Degen also became interested in the relationship of object to wearer. He made a series of brace lets that are simple wraps of black cotton coated with bee! Wax and graphite that must be wrapped on the wearer's wrist and secured by an assortment of pins, selected by the wearer. The result is a collaboration between maker and wearer. Paul Filmer found that this work was an "extension of the craft of making jewelry into the act of wearing it: a valuable contemporary re-assertion of the consummation of craft in use".

Also in the early 1980s Degen continued to explore the relationship between object and wearer by greatly enlarging the scale of his pieces. For a 1982 exhibition at the Crafts Council's gallery in London, he created objects that inverted the notion of wearer and worn. Rory Spence writing in the exhibition catalog noted that: "although Degen's work is becoming less and less conventionally 'wearable,' its relationship to the human body is paradoxically of increasing importance." Degen showed a giant pinwheel in a Claes Oldenburgian vein that was worn on the back. A rucksack filled with gardening tools and a bundle of brushwood had a touch of the Italian Arte Povera where the whole idea of the preciousity of art materials was challenged. A gaily painted ladder was to be carried over the wearer's shoulder, calling attention to the concepts of utility, adornment, and the use of jewelry as symbol. These works could be seen as "outsize jewelry, portable sculpture, or even tools with no definable use" as Spence suggests but for Degen as a jeweler it is the relationship of object to body that is key. The fact that these objects were made to be worn, even if for only short periods of time, changes them. They are not purely sculpture. They are more interesting to Degen because of that. "The fact that you can handle it and you can do things with your body to it, it creates possibilities that are not there when it's just an object. I'm not saying they are better possibilities or they're more exciting to the viewers, but certainly to me they are exciting," he explains.

These objects were not necessarily comfortable to wear, but discomfort simply as a way of emphasizing the relationship of object to wearer was not what Degen was aiming for. He conceived them as being worn for a short period of time, incorporating the temporal aspect of performance art or theater in his work. "If there is someone to wear it at the time when people see it, they can see it for a while , see what it does, see how it works, and then some photographs can be taken or video or whatever. I think that's it."

Some of Degen's strongest work is concerned with the relationship of object to body, materials, and theater, vis-à-vis content if not narrative. In 1986 during a residency as a visiting artist in Australia at the South College of Advanced Education, Adelaide, and at Curtin University, Perth, Degen began a series of gloves. The artist has continued the series since then, making a glove or two when an idea presents itself. The idea can be either content or materials driven. In Behind the Wall, there is a door in a wall and behind the wall a hand is trapped. The piece was inspired by a photograph with: "a text of a woman who had been tortured and she heard one of the chaps who was there making a phone call to his wife saying he was a bit delayed and he would be a little bit late at home. That's why in a way that glove came because you don't know what's happening behind the wall."

It is rare for Degen's content to be so directly influenced or inspired. More often it is formal issues that intrigue him although this does not preclude a message: "I had one that is just a heavy cotton tube and you put it over your arm and then you grab in your hand, a heavy steel bar. It's a hefty, heavy steel bar, black and then you put back the sleeve of it over your hand and you just see the knuckle and the steel bar and when you hold it and you see it, there's something really nasty about it. But when I did it, I didn't do it to be like that, but it just ended up like that. It looks like somebody is going to do someone in with that steel bar and the fact that it's masked as well, the hand, it is something very reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan with hooded people. But it didn't start with that in mind. It's just because I played with the material and suddenly I got that sleeve on and then I grabbed the bar with it."

The gloves are certainly not meant to be worn for long periods and they could be seen as small sculpture when not worn, but the fact Degen conceived them for the body endows them with greater potency. "The body is a very good vehicle for it, it's very good for the idea, it's a starting point because the fact that I decide that it's going to be wearable or you can put it, fit it on your body, it gives it its whole reason to be made," he says. "It's a catalyst to produce the work really."

The narrative aspect of the gloves and the prop-like characteristics of his larger body works could be considered a prelude to a new development in Degen's career. In 1992 he worked with the choreographer Emilyn Claid to create objects to be used in a dance as a part of a series at the South Bank Centre in London called "Craft-Dance Intermix" Although he admits that the collaboration was less successful than he would have hoped, he is eager to do more things for the stage and is currently talking with Angela Woodhouse about such a project.

Degen's career has been a series of explorations of what can be seen as the basic concerns of jewelry: materials, technique, symbolic power, symbiotic relationship of object to wearer, and preciousness. Jewelry is an intimate art for both the maker and the wearer. What Degen aims for in all of his work is to make it special, an intimate quality, absolutely personal, to transcend "all the factors, which are often so important to people: how long it took to make, is it beautifully crafted, is it expensive….lf, regardless of those factors, someone likes a piece or finds something special in it, then I think it's really great. It means the piece has got something, hasn't it?" Degen's work has got something special.

Karen Chambers is a frequent writer on the crafts. She lives in New York, NY.

Notes

All quotes, unless otherwise noted, are taken from an interview with the artist in London, 21 July 1995.

Neil Hansen, "Pierre Degen", Craft Quarterly, Issue 4, Summer 1982, p. 3.

Christopher Reid, "Shadowplay", Crafts, May/June 1979, pp. 17-18.

, p. 18.

Ibid.

Paul Filmer, "Pierre Degen: Jewelry", Crafts, November/December 1981, p. 51.

Rory Spence, untitled essay, Pierre Degen: New Work, London: Crafts Council, 1982, np.

Ibid.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.