A Profile of The Niessing Company

12 Minute Read

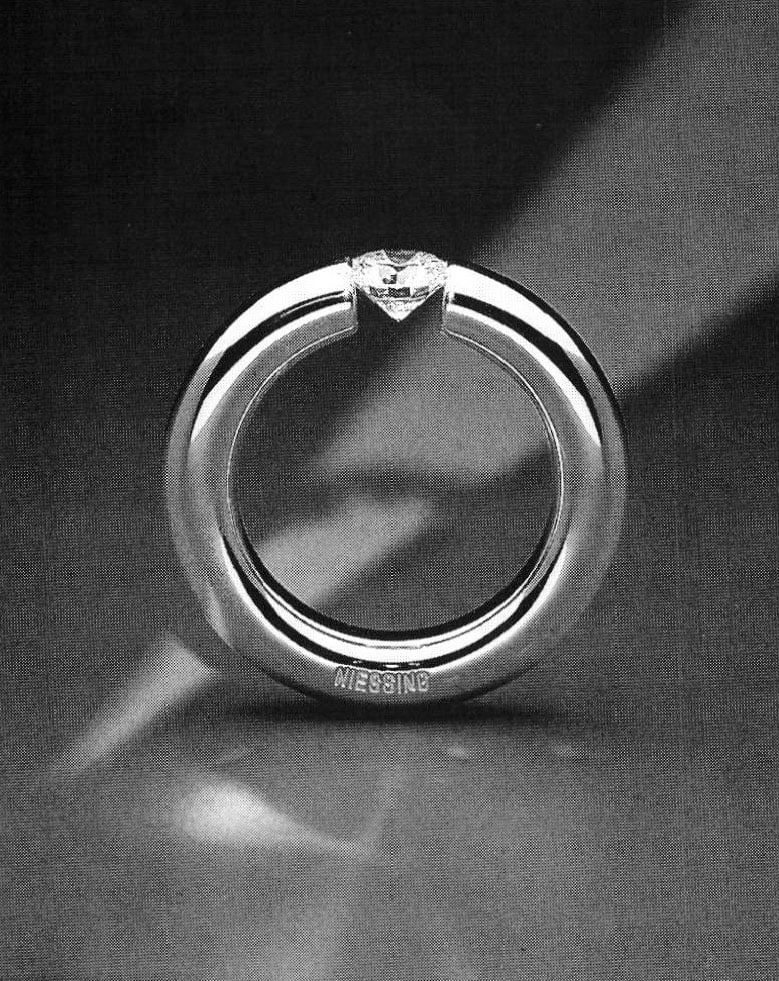

When we became engaged two years ago, we bought a Niessing tension ring, a simple band in which a diamond is held in place by nothing more than the pressure of the gold ring around it. The reactions to it have been interesting.

One friend, long married, regards the diamond trapped in its place by tension as the perfect metaphor for matrimony. Others, including many skilled and schooled jewelers, see the ring as an accident waiting to happen - they cannot believe the metal can hold a diamond fast.

For us, the ring provides one of life's delicious pleasures - the chance to have it both ways. We get to own a traditional symbol of betrothment and we get to confound those who insist that diamond rings require polished gold, huge rocks and little blue boxes marked Tiffany. We get to be conventional and we get to be different. We get to say something about who we are as a couple through our jewelry.

This, according to Niessing's manager, Jochen Exner, makes us typical Niessing customers. "We make jewelry for people who want to communicate with it, who want to express themselves through it," he says.

Despite the company's frequent use of technical wizardry Niessing's product is not about technique, nor is it about craft, despite the unusual emphasis on handwork. And, although Niessing works closely with artists and has had work in many of Europe's leading avant-garde exhibitions and galleries, the company will not be drawn into the "is it art" issue. "We have artists working for us, but we do not make art," says Exner firmly. The work is simply about good design. It would be at home in the Museum of Modern Art's late-20th-century design section, displayed between a Michael Graves teapot and a Movado watch.

Situated in northwest Germany, the company has a staff of 200, including 85 goldsmiths proficient in traditional handwork, 65 technicians specializing in computerized and high-tech machinery a sales force that works closely with retailers, and one full-time employee who deals with copyright infringements. The company also employs 3 artistically trained designers and hires other artist-designers on a freelance basis.

Hermann Niessing, a classically trained jeweler who apprenticed in Italy, established the company in Pforzheim in 1873. He left the German jewelry center several years later, moving the company to the picturesque town of Vreden, renowned for its pastoral beauty. "It was not a businessman's decision," says Exner, his great-grandson and a business school graduate. Nonetheless, the move turned out to have a profound impact on the company. Physically removed from the influence of the jewelry industry Niessing has found it easy to ignore trends and traditions.

In 1914, Exner's parents, Ursula Niessing Exner and Fritz Exner, assumed leadership of the company. A student of modern jewelry Ursula Exner remained a powerful influence until her death in 1986. She introduced innovative designs to the company and hired designers with art school backgrounds and a full understanding of process and material. As a result, the company, then known as a leading producer of traditional wedding bands, began developing the quintessential Niessing look - geometric and graphic forms, carefully finished and detailed, made with state-of-the-art technology whenever possible and age-old handwork whenever necessary.

One of the lines Ursula Exner designed during that early period of innovation and experimentation was Setario, a system in which rings of different shapes and shades of gold nest against one another. Brides and grooms who sought out the Niessing name, expecting the same gold bands worn by their parents and grandparents, found themselves fashioning their own configurations, creating their own spectrum of colors and design. Setario required the consumer to actively participate in the design process, to engage in a dialogue with the jewelry. The Exners were, in effect, training their own market.

The family's affinity for contemporary design was not the only factor propelling them in their new direction. Market studies indicating that the demand for wedding rings would soon fall off as a result of the declining German birthrate also played a critical role.

"When the studies appeared, we realized that our primary market would be significantly reduced in twenty years," Exner says. "It was then that we formulated our new product philosophy. We decided to do contemporary jewelry as our main line. We didn't want to be linked to one certain style of one certain period. We wanted to change as times changed."

Ursula Exner continued developing new lines, remaining fascinated by the work and ideas of the European art jewelry community including its repudiation of precious materials, a concept that intrigued the company but which they eventually rejected. "We finally concluded that, for us, material wasn't political - design was political," Exner says. "We felt there had to be a way to come up with a design philosophy that included precious metals and diamonds."

In the 1970s, Niessing made a concerted effort to incorporate platinum into its work. The decision was based on both aesthetic and business considerations. As the result of an aggressive promotional campaign by South African platinum mines, the metal was readily available and on the public's mind. Because the German jewelry industry had long neglected platinum, largely because of restrictions placed on its use during the war years, the look was fresh. "It gave us the chance to create a new look without forsaking precious metal," says Exner.

Niessing became known for its use of platinum, and in the early 1980s the company's facility with the material contributed to the development of the tension ring, arguably the company's most successful design innovation and technical achievement.

The invention of the tension ring is directly attributable to Ursula Exner's interest in contemporary studio jewelry. "We always had advisers and friends around the company whose ideas about reduction and minimalism influenced my mother very much," Exner remembers. "We decided to apply these ideas to our rings. We wanted there to be only one clean, pure style element in each ring - but we wanted that element to be very distinctive.

"We began trying to reduce the setting for diamonds. We kept reducing it further and further until someone jokingly suggested that we take the entire setting away and set the stone in the ring shank. Everyone found this very funny."

When the laughter subsided, the designers found themselves unable to let go of the concept. Almost to prove it couldn't be done, the team, which then consisted of Ursula Exner, Norbert Muerrle and Walter Wittek, began experimenting with prototype rings. They faced enormous technical problems.

It was silversmith Wittek who solved these problems and produced the first tension ring. Wittek fashioned a ring from platinum, at that time the only precious metal sufficiently static to hold a diamond rigid. He hand hammered and work hardened the closed ring, then cut the stressed shank. Next, he forced the exposed ends apart, creating an opening in which he inserted a diamond. When the expanded shank was allowed to contract, it trapped the diamond in place. After more than a year of careful scientific experimentation, Wittek was able to generate enough tension to hold the diamond securely. The physical qualities unique to platinum, with which the company was now so conversant, maximized the visual qualities unique to diamonds.

Never before had so much of a stone been unobstructed by its setting. The tension ring is the most significant aesthetic and technical innovation in diamond setting in recent memory. Like so much of Niessing's work, the ring also embodies the two most prominent design credos of the 20th century. In this ring, form definitely follows function and less is certainly more.

"We don't know why the tension ring has been so successful," Exner muses. "We do know that when you see it, you don't forget it. Perhaps this is because you can't believe what you're seeing. You see a diamond floating in air held only by the ring shank. You are astonished. You ask yourself, 'Is this possible?' 'Is this dangerous?'"

Several years later, through another exhaustive effort, Niessing perfected similar pre-stressing technology for a special 18k gold alloy. Today Niessing's design team continues to experiment with the tension ring, finding exciting new variations, improving on the technology.

The current team consists of Sabine Boning, a graduate of Elisabeth Holder's program at Dusseldorf, Pforzheim-trained Petra Weingartner, and Peter Eiber, who studied with Hermann Junger in Munich. A former member, Christine Kube, will soon be rejoining the team.

The team works in a separate building away from production staff and management. Observers describe the team as pampered, receiving from the company whatever it takes to meet their needs and foster their creativity.

The month of May, when Niessing's design year commences, is devoted to experimentation with little interference from management. "We might tell the designers we could use a certain product, like pendants or bracelets, or we may specify price points," says Exner. Otherwise, the team does whatever it wants, however it wants. "They can work on paper or in gold or whatever," says Exner. "They can work as a group or in their private studios. There are no requirements other than to be imaginative." Also during May, the company solicits ideas from the jewelry community at large.

As the year progresses, designs are evaluated, new production techniques mastered and samples distributed to retailers. Once introduced to the marketplace, new designs are given several years to catch on. "It generally takes three to five years for any innovation to be accepted by our market," says Exner. "That's something we learned over time and now plan for."

The designs produced in-house are attributed to the team as a whole. "We are interested in making the Niessing design, not in making individual reputations," says Exner. On the other hand, the freelancers, who have included such respected artists as Friedrich Becker in the 1970s and Annelies Planteydt more recently, do receive credit for their work as well as royalties when it sells.

Former design team member Matthias Monnich originally came to Niessing as a freelancer in the early eighties when his teacher, Hermann Junger, introduced him to Ursula Exner. "Junger walked up to my mother at the Intergenta Fair and said, 'Frau Exner, this guy has developed something I think you'll find interesting,'" says Exner. "She did."

The development Junger found so interesting is now marketed by Niessing under the trade name Iris. Iris, a gradation from 24k gold to 14k white, is produced by fusing more than 20 different but matched gold alloys. The visual result is a color change so subtle and seamless it almost appears airbrushed. Presented on neutral circular forms, the color quality of the gold becomes the design focus. The cool geometry of each piece is softened by the gentle color change and brushed finish. In its most effective application, a single interruption in the form provides a point of reference where the contrast in colors is at its most dramatic.

The Iris line and the tension rings are now part of Niessing's "Collection One," a group of work with relatively established appeal. New and more challenging work belongs to "Collection Two." Only a small fraction of the German stores to which Niessing sells is permitted to carry the complete Collection Two line. The company considers most of the second collection too avant-garde for current American taste.

In the United States, Niessing distributes its work through 10 independent galleries and its elegant retail store located on Madison Avenue in New York. The New York store, which also carries work by other jewelers such as Michael Good and the C.E. Dau Company, is intended as a model for other American retailers, an example of how the Niessing product should be presented.

"In deciding what to sell, we look to the demands of the public," says Exner. "My mother was very influenced by the Bauhaus tradition of making work for which there is demand. Were we to make jewelry for which there is no demand, we would no longer be a business. We would be an art workshop where individuals create for reasons other than business purposes."

As a businessman, Exner experiences the same frustrations as many individual art jewelers. "The voice of modern jewelry is not loud enough," says Exner. "It takes many years to establish a line, particularly for a small company. People appreciate design innovation in automobiles but resist it in jewelry. They accept annual changes in fashion, furniture and architecture, but it takes them years to accept any changes in jewelry. Even then, they always insist that jewelry maintain some classical feature."

For Niessing, that classical feature has been precious metal and stones. This sometimes concerns Exner. "There is the risk of attracting customers who are interested in prestige rather than communication," he admits. "Valuing only the preciousness of jewelry is detrimental to jewelry's success in the long term."

But Niessing rarely experiments with alternative materials. The company continues to specialize in small to mid-size series that can be mass produced in precious metals. Many of these series, once viewed as extraordinary innovations both technically and visually, have achieved the timeless quality of classic design. "We try to make products that are identifiable as ours," says Exner. "It would be flattering if, many years from now people saw our work and said, 'Oh, that's a late-20th-century Niessing.'"

Exner knows better than to expect such acknowledgment today. "Only one or two percent of the whole population cares about the kind of jewelry we make." Still, he is hopeful. "I see the market opening up. To live in Germany now and offer this jewelry is very exciting."

To see a company where artists and industry share common goals, where innovation and profits are not strangers, is also exciting. The door to public acceptance, closed so tightly to most contemporary jewelers, has been opened a crack by the small business in Vreden.

Donald Friedlich is a jeweler and Judith Mitchell is a writer. They live in Providence, Rhode Island.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.