Projects of Exploration: Visual Intricacy

8 Minute Read

This is the fourth in a series of projects for students, created to provide a forum in Metalsmith for provocative and innovative work. The projects will be assigned by a different professor each time. In this way, we hope to spotlight issues in all areas of metalwork, from sculpture to body adornment, from scale to preciousness.

This fourth project was assigned by William Harper, Professor of Art, Florida State University of Tallahassee. The problem was to create a pair of earrings that does not match but that each complements the other when they are worn together.

Information on the assignment for the next project appears of the end of the article.

PROJECT 4: VISUAL INTRICACY

I have always been fascinated by the great monumental earrings of certain archaic cultures-the superhuman assemblage ear ornaments of gold and stones in the pharonic falcons from Tut's tomb; the Estruscans' almost mystical configurations of shimmery gold granulation and chain; or the miraculous earspools of bone, shell and inlaid stones from ancient Peru.

The Fulani people of Mali still make the huge 14k gold, triple-bladed ornaments that have an almost Grand Guignol sense of danger as the weight distends the ear, held by the red silk wrapped piercer. The size and elegance of the silk's menacing gold blades combined with the blood-red silk cannot but stimulate a sense of erotic pain to Western eyes. None of these pieces was easy to wear.

They required commitment on the part of the wearer, a commitment of discomfort and even pain in the preparation of the earlobe and then even more commitment in the actual act of wearing them. It is true that some of these jewels were meant for burial purposes, but more often they were meant to be worn by the elite of the culture as a sign of power, as an act of ceremony. These were complex adornments, symbolizing wealth, power, taste and/or style, commitment, perhaps even psycho-sexual overtones. They were grandly theatrical, spectacular both on and off the body.

With these thoughts, I assigned this visual intricacy problem. There were more than 50 entries, but surprisingly few seemed to focus on the concept of intricacy. The majority of pieces were simply conceptually weak, seeming to organize themselves into two groups either the school of late 80s cliché-style zig-zags, triangles and wire spiral—swarmed-over Memphis, with the obligatory strip of anodized aluminum; or the school of jewelry that begins and ends with technique, in this case, lamination of one boring shape onto another. There was also a third sub-group of hang a lot of stuff together to dangle." The pieces I have chosen as finalists avoided these pitfalls and began instead with some type of visual idea—creativity, rather than the mere act of making something.

Linda Marie Oliver-Matt's (University of Illinois, Champign-Urbana) huge sculptual ornaments perhaps most reflect those attitudes of the archaic cultures—size, theatricality, commitment to the act of wearing—but this style is thoroughly 20th-century constructivism. She describes her intent as "to encompass not only the ear of the human body but the whole head and face with curvilinear lines. I feel that the simplistic line of the earrings forces the viewer to look not only at the wearer, but also the space around the wearer."

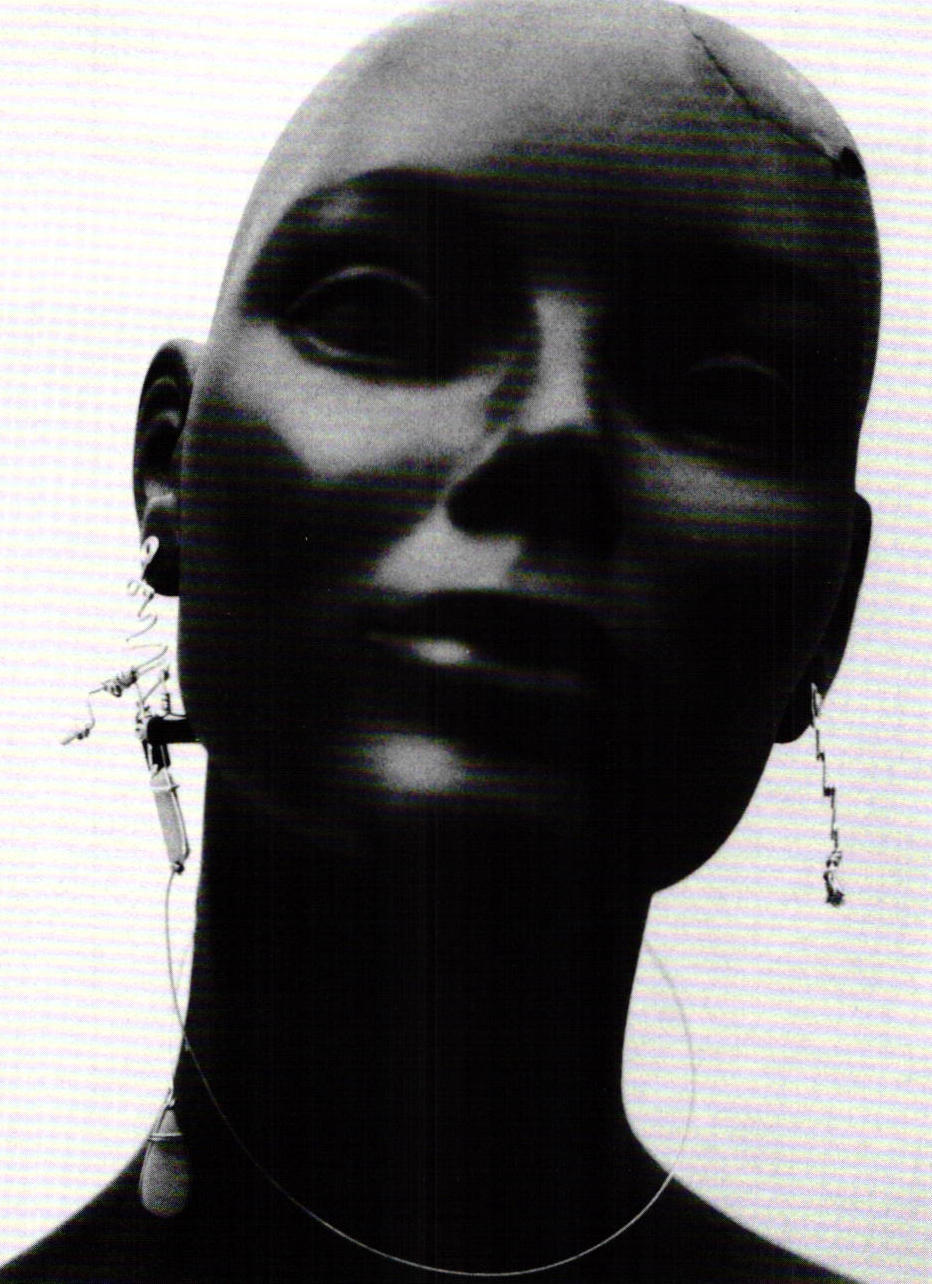

The silver and shaped-plastic pieces by Kelley Reese (Maryland, Institute College of Art) also interact sculpturally with the body, but by wrapping around the neck, they define it, setting the head apart. They are not only earrings, but also a kind of torque, a simple neckline with a flourish of elegant surprise at the ear.

In terms of pure elegance and dramatic wearability, four entries distinguished themselves as a group. Liz Kreutzberger (Center for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI) wished "to express the process of confusion and noise entering through one reluctant ear and filtering out in a screened, orderly fashion through the other." The "reluctant" part is kinetic, while the filter is really a mirrored sunglass lense set with silver elements. These meet every aspect of the problem brilliantly—an idea with wit!

Margaret Boor's (San Diego State University) pieces of silver and 14k gold are the most volume-oriented. Again, extremely elegant, flowing forms define the line of the jaw, enclosing the face. These are full, robustly formal pieces that stress monumentality without appearing to be weighty.

Kain Bochenhauer's (San Diego State University) silver, gold and tourmaline pair are primarily concerned with heavily textured cascading discs, which again define the jawline and the face. They are fragile in feeling without sacrificing significant size.

Erika Ayala's (University of Michigan) surprisingly simple pieces of stainless steel, gold leaf and paper surprise in choice of materials and delicacy of form yet retain a sense of drama through the implied danger of the act of wearing them—the tensile stainless wire tauntly balanced through the lobe.

The entries by Jeffrey Saiden (University of Michigan), and Leslie Ott (Center for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI) share similar intent. Visually, they are the simplest pieces of those being discussed. Certainly they could not really be classified as visually intricate. However, I have chosen to include them because of the manner in which they can be worn in the same ear, or in separate ears. This versatility would seem to preclude too much extravagant detail, but rather, necessitates a more open form of design organization.

It is rare that a real sense of wit ever enters the realm of jewelry. Many pieces attempt to be funny or humorous, often engaging in poor punning, but light, witty statements are rare, especially if they have slightly darker undertones. The final three entries to be discussed possess this characteristic.

Elizabeth S. Westerman's (Center for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI) Cephalopod with "Dead Man's Finger" is really two pieces (or three!) in one. It is a ring, which, when disassembled, assumes various configurations, either together or separately. Although small when worn on the ear, the entire object has an uniformity that is unique among the entries.

Lanie Todd (Maryland Institute College of Art) entitles her entry Cities in Flight. Composed of a "starship" and a "dust mask," the piece concerns itself with the Earth's future and how some of us will have a means of escape, and others will have to cope with being left behind. This is undoubtedly the most difficult of all the works discussed, both in its conception and its wearability. Conceptually, it deals with sociological psychological fears, big ideas not easily tackled by "the precious realm of body adornment."

To further complicate matters, one seems to become lopsided when wearing them. In addition, they invite the viewer to get close to the wearer, to perhaps reach out, to touch, to invade privacy by touch. This can be disconcerting to many people, when relative strangers pass a certain boundary of "look but don't touch." These earrings are so novel, so loaded with intent, that one must expect such actions on behalf of the viewer. But then when one would wear such unique work, she must expect attention from the curious. The psychology involved in wearing the unusual is more complex than that of wearing the usual status-symbol adornment.

As a final burst of the outrageous neo-dada or late 20th-century surrealism—we have Rebecca Coldren's (University of Michigan) Fish Earrings, although Earplugs, would be a better description! They are in a class by Themselves—a zany creation that goes beyond taste—good or bad—but certainly not indifferent. They exemplify jewelry for the brave, for the uninhibited, with no sense of the pretentious "jewelry-as-performance" school. They make us laugh, force us to question body adornment. They brighten our day.

PROJECT 5: HONOR SOMETHING ORDINARY

Project 5 is presented by Lynda Watson-Abbott, Professor of Metals and Jewelry, Cabrillo College, Aptos, CA.

Project: To honor something ordinary with a wearable piece of jewelry or a functional object. Jewelry/metal has been used historically to honor famous people or commemorate notable events or accomplishments. Here is your opportunity to immortalize someone or something you think is wonderful or important.

Think about food, places, events, activities, objects or friends that are special to you—and maybe you alone. How could you best represent or symbolize your chosen subject? Think about traditional ways of showing importance or drawing attention. What else could you do? The materials and format you use should be appropriate to, and enhance, the message.

Deadline for submission is December 1, 1988. Students must be currently enrolled in a metals program at the undergraduate or graduate level. Black-and-white photographs and/or 35mm slides documenting the work should be forwarded to: Lynda Watson-Abbott, 418 Darwin Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95062.

Photographs/slides must be accompanied by: 1. maker's name 2. college or university (indicate undergraduate or graduate) 3. address and telephone number 4. tide of work 5. pertinent descriptive information 6. materials/technique 7. dimensions 8. date completed 9. photo credit 10. statement of intent.

IMPORTANT: Photographs are critical to the success of your work in print. Please pay attention to lighting, composition, focus and background color.

Related Articles:

- Projects of Exploration: The Art and Science of Line

- Projects of Exploration: Performance and Beyond

- Projects of Exploration: Honor Something Ordinary

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.