Recent Sightings: Designer-Craftsman

5 Minute Read

This article series from Metalsmith Magazine is named "Recent Sightings" and here Bruce Metcalf talks about art, craftmanship, design, the artists, and techniques. For this 1987 Spring issue, he talks about the label Designer-Craftsman.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you peruse an issue of Crafts Horizons from the mid-60s, you are likely to encounter a label frequently applied in the crafts world: "designer-craftsman." This term was briefly applied to every type of crafts endeavor and even used as an umbrella for the whole field. For instance, the major crafts organization in my state is still called Ohio Designer-Craftsmen. Although the term has since fallen out of favor, it expresses the ambitions of an entire decade.

By introducing the notion of craft alongside the notion of design, proponents imagined the field gaining an aura of professionalism and authenticity. No longer would laborer's hands be soiled, because he or she would graduate to the drawing board. No longer would the products of such labor be painstakingly produced by hand but mass-produced by industry in sensitive cooperation with the designer. The term projects twin goals of planning and manufacture, rather than unique hand-production. These goals were not enunciated by dropouts and hippies, of course, but by mature leaders of the field who came of age in the 50s.

The notion of a designer-craftsman was profoundly influenced by the philosophy of the Bauhaus. In the 30's, many designers called for a spirit of collaboration between man and machine. The designer was intended to be the intelligent tastemaker, the clear voice of reason, who guided industry into making functional and modern wares for the masses.

At the Bauhaus, each student was required to take metals, clay or fiber studio courses in order to know the materials and tools that give shape to a design. Such hands-on experience created a natural allegiance to craft. In fact, several Bauhaus students were later to become the first postwar generation of craft educators in America. They imported the idea of natural collaboration between artist and industry, as well as the religious zeal to transform the taste of ordinary citizens. In their vision, mass production was nor an agent of compromise and conformity but a means to improve the quality of life.

Logically, those Americans enthused by the Bauhaus vision saw great promise in mass production guided by the educated designer. But they also believed in first-hand experience with material. Thus the craftsman who aspired to industrial design; thus the term "designer-craftsman."

Two prominent silversmiths from the late 50s were teaching at Syracuse University when I was a student there in the late 60s. By then, however, one, Arthur Pulos, was Head of the Industrial Design Department, and the other, Lee DuSell, taught only design in the School of Art. They were practicing the ambition of the designer-craftsman—to become planners for industry. By then both had abandoned their craft entirely—the metalsmithing instructors at Syracuse were John Marshall and later, Michael Jerry.

My generation of students brought an entirely new value system to higher education. The rebellious spirit of the 60s found the concept of industry and mass production suspect: it smacked of selling out. This generation was not one to collaborate with the powers-that-be. We were much more interested in self-expression, in a minority sensibility and in self-reliance. It was the era of building your own kiln in the woods or of making beaded macramé for sale at Sunday crafts fairs. Our label was the "artist-craftsman," and we aspired to an. Only a small minority had ambitions to become designers of mass-produced goods.

Well, we all know what happened to that generation's naive idealism. Now that the supply of teaching positions has dried up and the romance of going out in the sticks and practicing an earthy craft has gone sour, talented young people are looking elsewhere for career opportunities. Many graduate from college-level jewelry departments that stress hands-on practice and they want daily engagement with material and process: the work of jewelry-making and metalsmithing is a labor of love. For many, the idea of craft presents a major compromise. On the other hand, they do not believe that commitment to the craft necessitates a vow of poverty. They desire a mainstream lifestyle, not based on deferred gratification and sacrifice but on comfort and relative ease. By and large, they look for jobs that pay them well for working with their hands. Like the 60s generation, however, many are not interested in compromise.

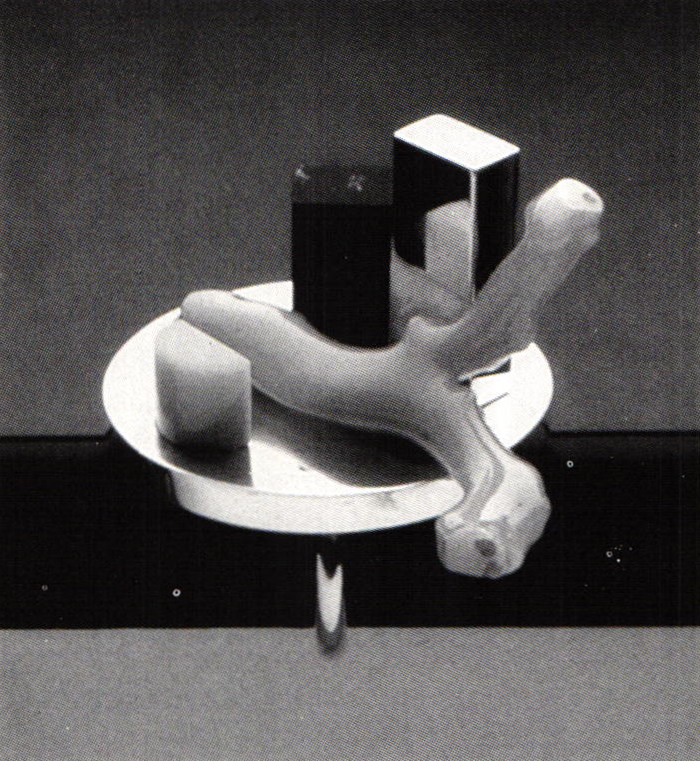

A new avenue appeared in the early 80s when the Memphis style of post-modern design burst on the American scene, full of vigor and irreverent humor, a fresh wind in the stuffy chambers of international design. I believe Americans responded intuitively to the energy, playfulness and apparent irrationality of the Memphis style. (Those three terms apply equally well to Funk Art, one of the most profound influences on students in the late 60s.) The immediate popular acclaim given to Memphis furniture and housewares encouraged many designers to seriously entertain the style as a valid expression of the times. In fact, Memphis has opened the door to a renaissance in crafts. In furnituremaking, the tired forms of Scandinavian Modern were suddenly superceded by colorful geometry, architectural detailing and a wryly humorous sense of form. Metalworkers are following suit, and an expanding market for housewares, furniture and interior decor encourages their aspirations. Recent success stories abound: David Tisdale is now designing for several international companies; Peter Handler is busy producing anodized aluminum and glass furniture in Philadelphia; Ivy Ross has opened an interior-design gallery in the East Village. Others, in a typically American entrepreneurial spirit, are seeking backers to start their own production lines.

Without fanfare or theorizing, we are witnessing the revival of the designer-craftsman, whose new role implies an evolution of the value system of crafts. The 50s appreciated the corporate man, the 60s celebrated the outsider, but the 80s proposes an impassioned insider. The new role model is an artist who, without relinquishing his or her values, uses the possibilities of design and manufacturing to exercise the heart's desire. The arena for artistic endeavor is now enlarged: the unique object is replaced by factory-made multiples. The potential of the machine is seen anew. A single design can thus have a significant influence; it can enter thousands of households in a few months, touching the lives of a vast audience previously inaccessible to the craftsman who produced unique or limited-production objects. Although the tools of design remain the same—color, form, content and material—the vision has changed. This generation does not see compromise but possibilities.

Bruce Metcalf teaches at Kent State and is a contributing editor to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.