Recent Sightings: Heart Pins

5 Minute Read

This article series from Metalsmith Magazine is named "Recent Sightings" where Bruce Metcalf talks about art, craftsmanship, design, the artists, and techniques. For this 1996 Spring issue, he talks about Pat Flynn's heart pins.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

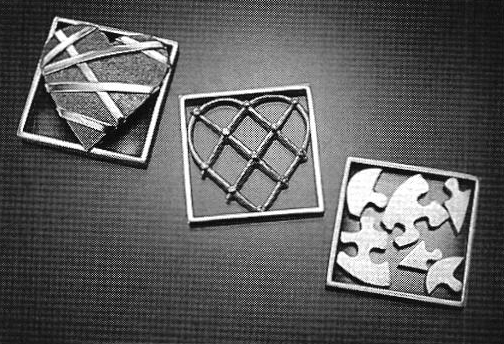

At the 1994 SOFA crafts exposition in Chicago, I decided to buy a piece of jewelry as a present for my lover. I wanted something within my rather limited means, and something that would clearly express my affection. Since the jewelry would be a gift - as jewelry often is - almost any design would make the point. But I wanted something specific to the emotion being expressed. In the end, I chose one of Pat Flynn's heart pins, in silver and steel. My lover was pleased with this unexpected token. When she wears it, we are both reminded of our mutual love and our mutual commitment.

This scenario describes one of the central functions of jewelry in our culture: to symbolize the bond between two people. Flynn's heart pins are a contemporary version of sentimental jewelry, in which the object is designed to become a tangible expression of feeling. While such feelings might be projected onto any imaginable object - even a vacuum cleaner, I suppose - some objects do the job better then others. Since the heart is the standard symbol for affection in this culture, and since jewelry remains one of the most permanent and intimate of objects, it's no wonder that Flynn's heart pins have proven so popular over the years.

However, a party-pooper could ask: "Is it art?"

To start with, the art world justifiably regards the heart as a cliché. No special talent or intelligence is required to use the image of a heart: it's as common a received symbol as there is in this culture. Regardless of what the heart may mean to me or my lover on a personal level, artistically, something unusual is required to remove it from the level of the crashingly ordinary. Of course, Flynn tries to do just that, by varying the surfaces and colors and textures of his many heart designs. But the image of the heart remains indelible, regardless of all the dressing-up it might receive.

Even worse, the heart pin trades in sentiment. Among hard-nosed skeptics, art and sentimentality don't mix. James Joyce called sentiment "unearned emotion", implying that the feeling is prepackaged and reflexive. One could think of any number of examples, from sending Christmas cards to people you haven't thought about all year, to the automatic greetings we extend to others every day. (Do we really care how these people are doing?) In this century, sentiment has earned a bad name because feelings are so often exploited for commercial ends, and we can't always determine the difference between genuine feelings and their imitations. Small wonder that sentimentality is often regarded with intense suspicion. And as a result, the heart pin looks like bad art.

The art world conveniently ignores an important fact though. Much sentiment is earned, and earned at great cost. Making love endure is difficult. Becoming an adult is a tough project. Life is hard. Should we be blamed for wanting to celebrate our occasional victories? Jewelry has long been used as souvenier and aide-memoir for important personal events. But the art world is uncomfortable with these kinds of vivid personal meanings unless they are regarded at arm's length, preferably ironically. It's as if all this personal life is too hot, too wild, or too messy for art to contain.

There's a snide phrase that art teachers sometimes use: the "merely personal". The phrase suggests that a personal meaning is so specific that it has no implication beyond its owner's life. The fact that I'm in love with a certain person means nothing to you, and nobody would suggest that when I lie in my lover's arms, it's art. Furthermore, intensely personal meanings like love are fugitive. The meaning does not live in the object, but in an individual's mind. ( A friend of mine once bought one of Flynn's heart pins for $15 at a flea market: evidently, a relationship that the pin once commemorated had collapsed, and the pin had been tossed out like an old pair of shoes. Losing its meaning, the heart pin lost its value. ) In contrast, art commonly refers to a level beyond the individual, whether we call that level universality, validity, or ambiguity. Art is ambitious for big things. To do something like serving as a symbol for two people's private sentiments might seem mere in comparison.

Western art's mandate points toward the universal. But craft - at least the kind of craft that Pat Flynn practices, which is intended to fit into our daily lives - points toward the personal. Art rejects the "merely personal" as trivial; craft embraces sentiments as essential to a life well-lived. Typically, we assume that art's role is more important, and that interest in the personal is of a lower order. However, I find no persuasive proof that our personal lives are so trivial, and I reject any hierarchy that places art over craft. Instead, the question is about difference.

By way of analogy, consider motor vehicles. A sports car is intended for one kind of use; a dump truck for another. But simply because the sports car can top 140 mph, we don't decide that it's superior to the dump truck. We realize that two different functions have evolved two radically different forms, and a qualitative hierarchy does not apply. My conclusion about art and craft is similar: they are vehicles of substantially different kinds. In the end, I do not think Flynn's heart pin is art, but it is very good jewelry. As a vehicle for the expression of affection, it works just fine. What painting or installation could do the job so well?

It's as if craft functions halfway between the particularity of our bodies and the exaltedness of art. Flynn's heart pin symbolizes and condenses powerful emotions, but close to the site of those feelings. The pin lives on my lover's body. Art lives somewhere else, farther away.

Bruce Metcalf is an jeweler, artist, and writer from Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.