Recent Sightings: Jewelerly Jewelers

5 Minute Read

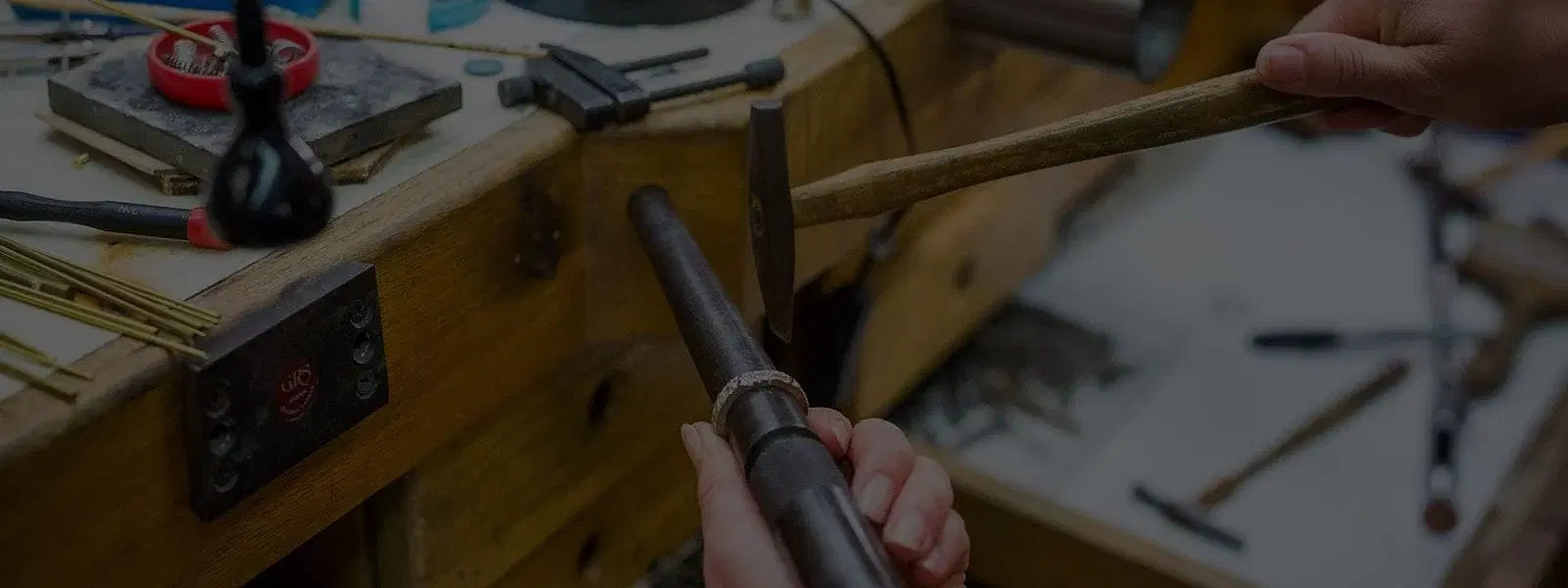

This article series from Metalsmith Magazine is named "Recent Sightings" where Bruce Metcalf talks about art, craftsmanship, design, the artists, and techniques. For this 1994 Summer issue, he talks about jewelerly jewelers.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There's a buzzword in the painting community: 'painterly'. I used to think it was pretentious; now I'm not so sure. A painterly painter is one whose application of paint is both skillful and gestural. John Singer Sargent or Willem deKooning are 'painterly": their paintings are full of lush brushstrokes and layers of color. The artists' 'touch', which is often compared to handwriting, is clearly visible. (On the other hand, Frank Stella of the 1960s, when his paintings were hard-edged, unmodulated stripes, would never be considered painterly.) It is an insider's term of appreciation for the sensual craft of painting, and those who pass the test are thought of as painter's painters.

If such a term exists for painting, why shouldn't there be 'jewelerly' jewelers? It couldn't be exactly the same thing as being painterly, because the craft is so different. A 'jewelerly' jeweler would have mastered the necessary skills, and would apply them in a virtuoso manner. But that virtuosity must be attuned to the scale and sensibility of jewelry: it couldn't be splashy or highly gestural. It would reflect an insider's love of the craft.

The granddaddy among living 'jewelerly' jewelers is Hermann Jünger, and his work shows several qualities that I think are useful to define what the word could mean. First, he has never expanded his scale even when all the 'New Jewelers' were making experimental body-sized ornaments. Jünger stayed close to the familiar Western restrictions for precious jewelry: his pins rarely exceeded about 2⅜" in any dimension. When he wanted to expand the scale of his jewelry, he arranged a number of coordinated small elements on a surface. Second, he has always exploited the traditional materials of fine jewelry - precious metals and stones - but in a way that is entirely contemporary, influenced by both abstract expressionist painting and African jewelry. Most of all, Jünger's work shows his amazingly deft touch: a subtle contrast of material, color, form, and surface; a confident mastery of his craft; and an unparalleled ability to instill a signature style of working into metal.

In the U.S. today, there aren't many jewelers who are very 'jewelerly', but among the best are Pat Flynn and Cheryl Rydmark. [See: "Simplicity That Speaks" in this issue of Metalsmith - ED.] I just saw Rydmark's new work at the massive Baltimore ACC show, and her work was like fresh breeze in an overheated room. Where other jewelers strain for effect, and where imitation is business-as-usual, the sensitivity and refinement of her jewelry was a true delight. Like Jünger and Flynn, she never works very large, she uses precious and semiprecious material, and she has a wonderful and subtle touch.

There are other qualities that might define the 'jewelerly' jeweler. Such work is always finely detailed, and fully resolved. Everything is considered: thickness of edges and bezels; the texture and color of the metal; the exact size and position of every element. Stones and metal and chains all fit together in a very satisfying way. And especially this: There is never a shortcut. Where lesser jewelers might use a simple or direct solution, Flynn and Rydmark use the best solution. They never use metal like cardboard. For instance, a standard tactic to produce a solid form is to bend a narrow strip of metal into a profile, and solder a top and bottom on. The resulting cube, circle, or donut is cheap and easy to make, but devoid of infection. Rydmark files down thick sheet metal into shapes with softly rounded surfaces and sharp edges. The result is probably more costly to make than a constructed slab, but far more interesting. In the end, Rydmark's shapes are resonant and lyrical in a way that a flat construction could never be. It's also no coincidence that she has done extensive historical research on the shapes she uses, and is fully aware of their possible meanings. Her care in choosing her shapes is extended into her care in making them.

The best 'jewelerly' jewelry never appears rigid or mechanical. It is a simple matter to achieve a perfect surface on a lathe, or to construct a crisp geometric shape, but these techniques produce cold and un-inflected forms. Rigid geometry allows little room for personal touch. If there is such a thing as a jeweler's unique handwriting in metal, it has to appear in subtle modulations of form and surface. When Pat Flynn makes his brooches from nails, he carefully forges and files each one. He makes no effort to achieve uniformity, but moves instead toward variation. Each nail is slightly different in the curve along its length, in size, and in the way it is filed. The purposeful irregularities of handwork act as a signature of the craftsman, and a symbol of the human presence infusing the object.

Flynn's and Rydmark's works are beautifully finished. Both artists employ a number of different finishes in each object, contrasting polished edges with filed surfaces, and dark metal with bright metal. But for all the variety, each finish is totally consistent in itself. Wherever metal is polished, it is perfectly polished; where it is filed, the filing is uniform. Again, the 'jewelerly' finish is characterized by complete resolution and fine craftsmanship.

There is also an intangible quality that permeates Flynn's and Rydmark's work. Metalworking is a difficult craft, and ultimately the jeweler's motivation makes all the difference in the world. In a world that rewards the superficial, familiar, and cheap, a special resolve must keep the jeweler at her bench, making only the best that she is capable of making. I can find only one possible explanation: passion. We are accustomed to thinking that passion in the visual arts is manifested in grand, theatrical gestures, but here is another type of passion, a passion that is manifested in patience, painstaking labor, and a refusal to compromise. Both Flynn and Rydmark set a high standard for themselves, and they always live up to it. To the trained and sympathetic observer, it's evident that their standard is based on love: a love of the labor of jewelry-making and a love of jewelry. It's visible in Pat Flynn's perfectly polished bezels set in iron, and in Cheryl Rydmark's impeccably shaped pendants. They're just so good at loving what they do. That is why they are true jeweler's jewelers.

Bruce Metcalf is a metalsmith and a writer on the crafts. He lives in Philadelphia, PA.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.