Samuel Yellin – Sketching in Iron

By the mid-nineteenth century, European ironwork was in decline due to innovations brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Cast iron was replacing the more time-consuming and skillfully made hammered iron, driving the decorative smith toward extinction. A French historian wrote that the last piece of decorative ironwork to be produced in the 'glorious tradition' of wrought iron was made in 1809 and surrounded the choir in the Cathedral of Notre Dame. One hundred years later - in 1909 Samuel Yellin established a blacksmith shop and attempted to recreate the quality craftsmanship found in historic ironwork.

10 Minute Read

By the mid-nineteenth century, European ironwork was in decline due to innovations brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Cast iron was replacing the more time-consuming and skillfully made hammered iron, driving the decorative smith toward extinction. A French historian wrote that the last piece of decorative ironwork to be produced in the "glorious tradition" of wrought iron was made in 1809 and surrounded the choir in the Cathedral of Notre Dame. [1] One hundred years later-in 1909-a young émigré named Samuel Yellin established a blacksmith shop half a world away and attempted to recreate the quality craftsmanship found in historic ironwork.

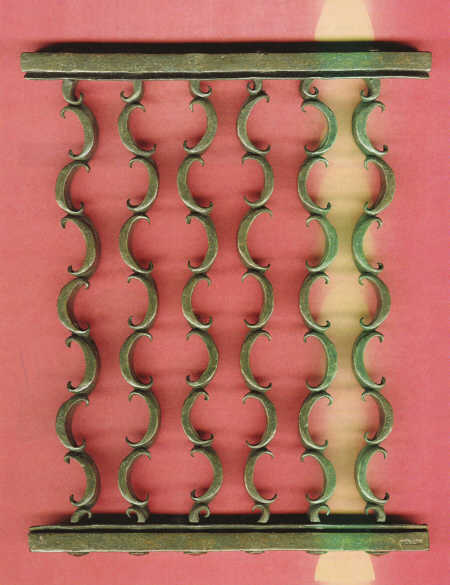

| Iron Sketch, 1930s forged wrought iron 10 1/2 x 13 x 1 " |

Born in 1885 in a village near the Austrian boarder, Samuel Yellin apprenticed with a well-known Polish smith when he was only 12 sears old. For the next five years, in the traditional manner, young Yellin learned blacksmithing as a trade, a craft, and an art. In the journeymen phase of a typical European education, a novice smith was taught to recognize how lessons practiced during an apprenticeship fit into the broader context of a chosen field. In 1902, when Yellin left Poland to see ironwork throughout Europe , he reportedly had already achieved his master certificate. Within a few years, he left Europe to join his family in America . In Philadelphia he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art (today's University of the Arts) and was soon incited to teach a metalworking class.

Yellin established his first studio in 1909 with $150 of out-of-pocket capital. Inconveniently located on the top floor of a corner building in South Philadelphia , the site forced him to haul material up-arid finished pieces down through an open window. In 1915 he moved his operation to 5520 Arch Street , where he would work for the rest of his life. Yellin called his business "Samuel Yellin Metalworker," a name that mould become synonymous with craftsmanship as his career progressed. "Samuel Yellin Metalworkers" is still in operation under the direction of the founder's granddaughter, Clare Yellin. In identifying himself in relationship to his material-as a "metalworker" rather than as an artist or sculptor Yellin consciously promoted himself as a craftsman.

| Samuel Yellin at the forge with a striker on his right, circa 1925 |

In 1911, Yellin was commissioned to make an entrance gate for J. P. Morgan's Long Island estate. From then on, his documented output was so prolific that by the next year he was described in The Craftsman magazine as an ironworker "without peer" a nice compliment for someone still in his twenties. Founded in 1901 by furniture maker Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman was a nationwide forum for discussions of craft, the arts, and related values of quality and simplicity. The author credited Yellin as having (almost single-handedly) revived the craft of wrought iron, noting, "The very spirit of the fire that forged it seems imprisoned in the graceful forms of the iron, and the ring of the hammer on the anvil seems almost to echo in the eat." [2]

An early Yellin piece, made in 1915, illustrates the grace of the artist's hand. An iron bar was delicately drawn out to a fine taper to create a web of interwoven leaves and vines. Each subsequently smaller branch intertwines to form a harmonious whole with an Art Nouveau lyrical fluidity. Such "graceful forms" would characterize Yellin's work regardless of scale.

Yellin believed that appropriate design must be evident even in the smallest architectural detail, a belief made manifest in an iron door plate he fashioned, circa 1920. The outlines of the push plate converge and flow into a foliate terminus. In turn, the design rolls into itself as if to point the way for the hand to find its place and open the door. Surely a push plate would be considered a minor architectural element, but Yellin, through his subtle handling of the metal, imparts a sense of strength and grace to its modest form. Whether large or small, for public or private space, Yellin's work was meticulous in its attention to detail.

| Iron Sketch, 1930s forged wrought iron 10 x 15 x 1 " |

John Ruskin, champion of fine craftsmanship and the authoritative cultural voice during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, could have been describing Yellin's work when he wrote, "True ornament [must] be beautiful in its place, and no where else… [It should] aid the effect of ever portion of the building." [3] Yellin himself stated, "It is most important that a piece of work shall be harmonious from ever point of view… for a piece of craftsmanship to be good not the smallest part should receive adverse criticism." [4] Yellin was likely familiar with Ruskin and contemporaneous aesthetic theory through lively discussions with clients and architects, collectors and curators.

Indeed, Yellin's work put him in touch with the rich and the powerful, patrons who read like a Who's Who of American industrialists. He produced work for sumptuous estates: Vanderbilt on Long Island, Mellon in Pittsburgh, DuPont in Wilmington, Eastman in Rochester, Ford in Detroit , Heinz in Pittsburgh. His commissions for important public spaces were many, including the Cloisters; universities including Princeton, Yale, Harvard, Columbia; the Grace Cathedral in San Francisco; and the Washington Cathedral in Washington D.C. Much of Philadelphia 's historic ironwork came out of Yellin's shop.

| Vine Fragment, 1915 forged wrought iron 14 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 1 1/2″ |

Aided by his own staff of draftsmen, Yellin insisted that working drawings be mounted to the wall so that he - along with clients, architects, and staff could view them. This process allowed for developmental discussions of design elements, construction techniques, or changes to a commission. A period memo illuminates this process: "All drawings … when they are completed, must be hung up on the wall, so that Mr. Yellin can see everything without having to ask for drawings, in order that nothing may be overlooked." [5]

Yellin shop drawings were important communication tools, carrying the details of each piece from design through installation. But drawing alone was not sufficient for the self-proclaimed "metalworker." From both an aesthetic and practical standpoint, Yellin insisted that designs be worked out in metal. He acknowledged meteriality intuitively and, as he matured professionally, had more opportunities to share his ideas with an appreciative audience. An entry he wrote for the Encyclopedia Britannica expresses a romantic materialism as well as a dedication to process:

[A] real study of details can only be accomplished on the until…. This actual study in the metal … can only come from a deep knowledge and love of the material. The making of beautiful ironwork cannot be fully described and illustrated on paper; it is often necessary for the craftsman to make sketches in iron. [6]

Such "sketches in iron" form a collection of sample design fragments that serve as a window into the artist's creative process. Harvey Yellin recalled his father explaining how working in three dimensions encouraged his creativity:

We made… many detailed drawings, but when I began to work them on the anvil, they shaped themselves quite differently from the way they appeared in the original sketches. The creative spirit… like a winged thing … must have freedom in which to sing and soar. [7]

| Iron Sketch, 1930s forged wrought iron 2 x 16 x 1″ | Untitled Sketch. 1930s pencil on vellum 8 1/2 x 11″ |

| Iron Sketch, 1930s forged wrought iron 19 x 21 x 1 1/2″This study was for a gate at the Washington National Cathedral, Washington D.C., 1935. |

Yellin's studio benefited from the building boom that swept the country in the first rears of the twentieth century, when studio craftsmen received unprecedented support and shared a common belief in basic aesthetic principles. Ruskin had warned against, "The suggestion of a mode of structure or support, other than the true one…. The painting of surfaces to represent some other material than that of which they actually consist…. The use of east or machine made ornament of any, kind." 8 In American studios these forbidden practices were translated and discussed in positive terms of exposed or "honest" construction, truth to materials, and the inherent value of handwork.

Subscribing to the idea that. craft work should foster "truth" about its material, Yellin chastised architectural practices that did not adhere to such principles. In 1925, in an article he wrote for the Western Architect that initiated an important dialog between craftsmen and architects, Yellin attempted to define a working relationship that would allow for a fruitful collaboration between them:

Is it right that metal should be modeled as clay-or as carved wood? Does it indicate that the material has been worked as that material should be worked? Does it indicate the craftsman's unashamed love for his material and for his method of is working it? The answer is 'No.' [9]

In the same article, Yellin explored the question of craftsmanship, calling for exposed or "honest" construction and concluding:

But what is real craftsmanship? Is it the designing and production of work by methods tricky and inventive that will make the public marvel … Or is it the working out of good design in proper materials, in an honest tray?

Part and parcel of the "honest way" of working out a design involved Yellin's method of solving problems in three dimensions. Overall concepts could be presented initially on paper, but Yellin insisted that refinements be worked out as a "sketch" in metal. "What is put on paper only indicates in general what is wanted…. The real, artistic value of this work must be expressed with the hammer [original author's emphasis]." Placing such value on the expressive quality of handwork supported the idea that manual labor contributed to the authenticity of form (its "artistic value") and to the dignity of labor. [10]

Yellin resisted the twentieth-century move toward separate, specialized tasks that would replace the nineteenth-century craftsman's skill. During a period when the Ford Motor Company introduced the chain-driven assembly line, simplifying each worker's task and regulating the speed at which each performed, Yellin's shop retained the essence of individualized labor that characterized American studio craft, at least in theory.

A discussion of Samuel Yellin's oeuvre is not complete without mention of the ironwork he made for the Federal Resume Bank. Throughout his career he completed several bank interiors, including Equitable Trust in 1926 and a beautiful tellers' screen for the Central Sittings Bank, 1929. Yellin's work in the 1920 for the Federal Reserve was, perhaps, the largest commission of wrought iron ever created in the United States . To complete such a massive installation, he fashioned 200 tons of wrought iron, a feat that rivaled the output of many large factories of the day. Yellin's operation grew; he added a second building to the Arch Street complex and eventually employed more than 250 men.

The 1930s brought with it the Great Depression and a change in aesthetic preference that favored machined simplicity. As demand for Yellin's work declined, he kept as many smiths on the payroll as possible, diminishing his personal resources. At his death in 1940, Yellin left behind thousands of drawings and photographs and hundreds of "sketches in iron."

Samuel Yellin's emphasis on the materiality of his designs places him alongside Gustav Stickley and Annie Albers as an early master of the Studio Craft movement. the first generation of American craftsmen to make their mark on the new century would attempt to formulate a theory in which their work would be appreciated on a par with fine art, drawing from the theories of Ruskin and his disciple William Morris. These efforts coalesced into a movement that would sweep the nation into a new millennium. Theirs was a search for a true American style.

While Samuel Yellin will ill be remembered for his masterful work in iron, he was adamant in his intellectual adherence to what I call the Craftsman Ideal. In lectures and writing, Yellin translated this ideal into a language consistent with his own experience. At the height of his mature career, Yellin taught at the University of Pennsylvania , lectured at the Architectural Club of Chicago and Architectural League of New York, traveled to Europe , and consulted for the Philadelphia and Metropolitan museums. Yet he continually refined his persona as craftsman and underscored his identity by self reference as a "blacksmith." In his insistence on design suited to function, his use of appropriate materials, and application of proper techniques, Yell in epitomized the search for a craftsman ideal.

| Samuel Yellin admiring his lights and grille work at the reactor Reserve Bank of New York, New York City, 1925 |

Footnotes:

- [1] Henry Havard, Dictionnaire de l'ameublement et de la decoration (Paris, 1888-92) as quoted in Richard Wattenmaker Samuel Yellin in Context ( Flint , 1985).

- [2] C. Matlack Price, "A Modern Craftsman in Wrought Iron: Work that Rivals the Industrial Achievements of the Middle Ages," The Craftsman XXII, no. 6 (1912): 627-634.

- [3] Ruskin, "Treatment of Ornament," Stones of Venice numbered Artists Edition (NY Merrill & Baker, 1851) 236.

- [4] Samuel Yellin, "Design and Craftsmanship," Architect Club of Chicago (lecture) 1926.

- [5] Samuel Yellin Metalworker, Memo, June 20, 1930 .

- [6] Samuel Yellin, "Iron in Art," In Encyclopedia Britannica, 1925; 14th ed. (1940) 679.

- [7] Harvey Yellin, 13

- [8] John Ruskin, Seven Lamps of Architecture, numbered Artists Edition (NY Merrill & Baker, n.d.) 39.

- [9] Sam net Yell in, "The Architect and the Craftsman," Western Architect (Sept. 1929), 93.

- [10] Yellin, 93.

Anna Fariello, an independent curator with Curatorial InSight, is co-editor or Objects and Meaning, forthcoming from Scarecrow Press. All photographs courtesy Clare Yellin, Samuel Yellin Metalworkers.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.