Susan Hamlet: Culture Of Materials

9 Minute Read

"Culture of materials," an expression originating from the early 20th-century teaching of Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, defines the artist's deliberate examination and selection of materials for use in the art-making process. This examination and application defines the form and concept being rendered. Today, Susan Hamlet could be seen to echo Tatlin with her own "culture of materials." Her ability to work both traditional and contemporary materials is important, as form, function and material become interdependent for the success of her pieces. Utilizing precious and base metals, as well as rubber, plastic, industrial hardware and readymades, she produces a substantial quantity of work in a variety of forms and functions: jewelry, wall reliefs, vessels and vessel forms.

The jewelry, executed in thin-gauge wire and sheet of high tensile strength, is light weight and durable. Great effort is put into developing mechanisms for attachment and systems of construction that make use of the metal's flexible properties and at the same time define the piece's shape or form. Hamlet's early jewelry, called Flexible Columns, are neckpieces and bracelets constructed of springy, stainless steel wires that pass through a progression of ribs or spacers. Seen off the body, or in the uncoiled state, the piece is a long, resilient taper. The taper and cross-section are defined by the placement and diameter of the ribs. In as much as the wires pass through, but are not physically attached to each rib, the column can be curved and twisted and wrapped around neck or wrist. By inserting the small end into the large end the piece springs against itself, creating a secure closure. When released, the piece has a life of its own and returns to a taut, linear posture. The development of the flexible column system is a result of extensive calculation and experimentation. This system requires a predetermined diameter for each rib and predetermined distance from one rib to the next. A specific metal in a specific condition and configuration is necessary for such flawless functioning.

Hamlet's Shim Pins operate on mechanical principles similar to those of the Flexible Columns: construction and material properties simultaneously define form and mechanism. Sheet metal is the main component in these pieces, allowing the work to become planar. The pins are made of thin sheet metal called shim stock. In this case, stainless steel approximately. 005 to .010 inches thick (a very springy material) may be deflected or torqued in and out of shape many times without losing its flexible quality. The shim is a simple and durable mechanism, cut to shape and arched, becoming both the body of the pin and the motor or activator of the mechanism. This arched shape is flanked by sterling and stainless bars that are compositional elements as well as levers which transmit the movement of the shim to the mechanism. When the arched shim is pressed flat, the levers separate the pin stem from its sheath, allowing the user to affix the piece to a garment. When the compressed shim is released, the pin stem enters its sheath and the pin is secure on the garment. The forms are essentially crescent or semicircular and bent to create the necessary arch. Edges of the arched crescent shapes are reinforced by the mechanism's levers. These billowy, smooth shapes, with their rigid perimeter, appear much like sails or fans capturing wind, defining movement. Their thin, light quality aids not only their use but also emphasizes the sail-like notion. Conceiving and developing systems of construction and attachment are of primary concern in the Flexibe Columns and Shim Pins; esthetics surrender to and are a result of these demands. Hamlet's investigative nature and understanding of metals and their utilization are rewarded by evidenced her successful manipulation of these systems and their perception as esthetically pleasing.

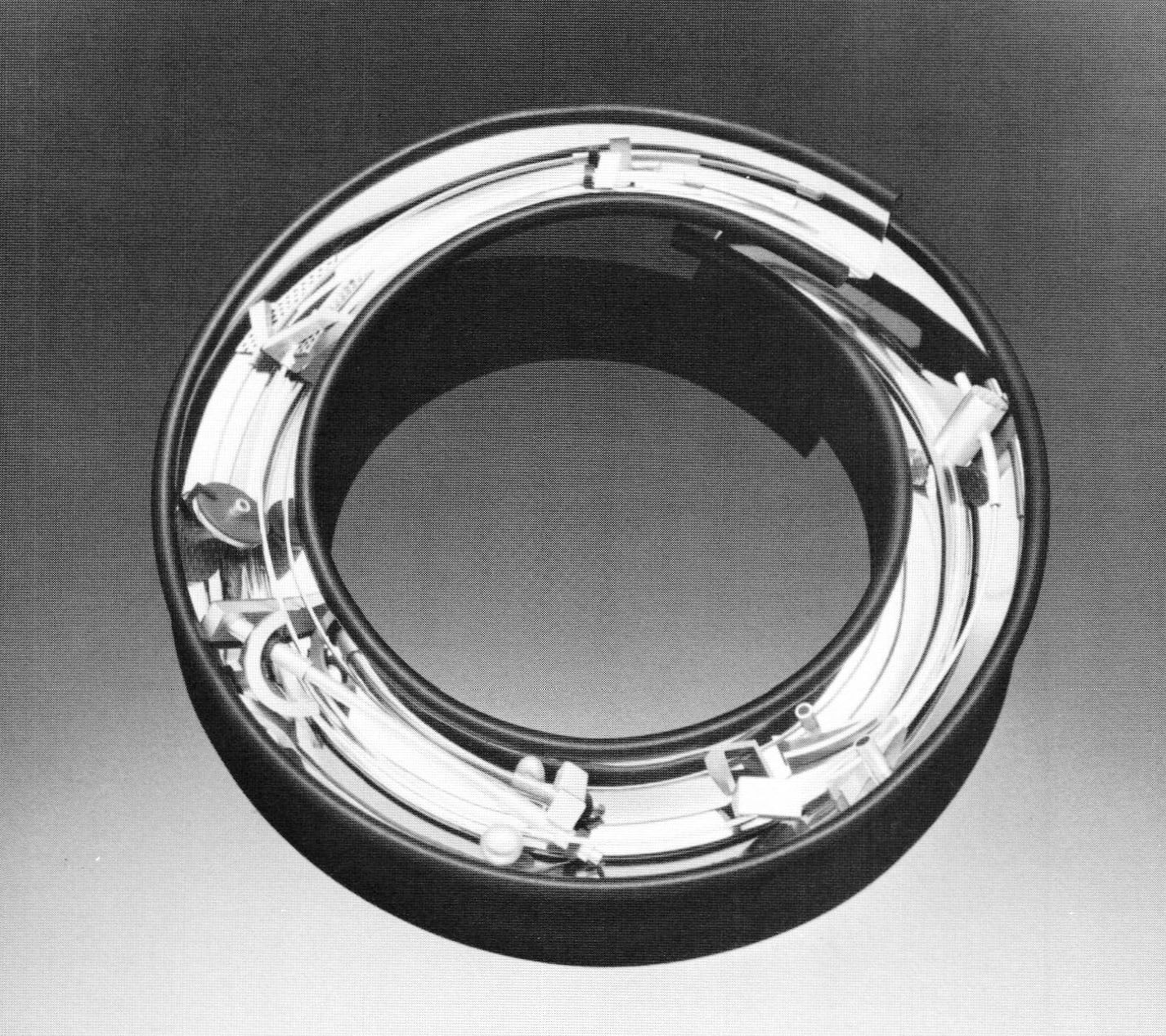

Reflectiveness in the metal surface is an effect exploited in Hamlet's series of Shim Bracelets. The bracelets are highly polished stainless steel channels or troughs curved around the wrist to form an open-ended circle. Within the trough are randomly placed elements: wires, tubes, colored plastic, mesh, all appearing to float and multiply in what the artist characterizes as a ". . . riot of movement." The random, whirling effect of this reflective interior has an illusionary and chaotic quality, eliciting a tense and anxious feeling. This chaotic sense becomes a metaphor of the often intense and frenetic schedule and activity of the artist. The edge of the metal trough is clad with black rubber piping. Compositionally, the rubber serves to define the edge of the reflective surfaces, and visually, it contains the active surface decorations. Practically, the rubber protects the wrist from the thin, sharp edge of the stainless steel shim when worn. The illusionary and chaotic effects serve another end. The bracelets become what one might perceive as a sensory device, a means to carry the piece beyond the static state. Much like a powerful painting or musical performance, more than canvas and pigment or notes and ledger, they elicit response, mood and emotion. This effect also relates to Hamlet's frequent reference to the "scientist, whose experiments (the static object) are only physical steps to yield greater finds in terms of enlightenment and theory (the sensory or emotional response)."

Another area of investigation is Panel Studies, small, triptych wall reliefs comprised of narrow rectangles of plastic or metal arranged on a larger field. Their surfaces are decorated with elements that might be described as mechanical hieroglyphics. The elements are made of wire, sheet, industrial mesh and shards of plastic and rubber. The characters are defined by the artist as both compositional and self-referential. The placement of the elements on the panels make compositions that read as conflict and resolve. The panels have areas that appear to be openings or small windows, an illusion to passageway or threshold. In some instances there is a cluster or congestion of elements trapped over an opening; others have elements floating freely within and through the passageway, further defining the idea of conflict and resolve. Compositionally, they are strong, but they seem to serve another end as well, as a therapeutic or cathartic act for their maker.

Hamlet has used the vessel or vessel reference in past and present work. Holloware Constructions #2 and #3 have many of the visual and material characteristic of the Shim Bracelets applied to what appears to be a vessel form, an inverted cone, its peak removed, perched atop a stilted base. Bottomless containers or flaring openings—are they surfaces to be decorated? Although they amply impart the sense of illusion and chaos, the viewer is left curious as to why they resemble vessels.

Where the viewer is left questioning the vessel reference in the Holloware Constructions, the new Bowl Series 1-7 is bold and decisive. Unquestionably vessels (having bottoms), they can be used. The artist's intent is to use the vessel as art form and symbol, as well as to rekindle the public's interest in holloware. Visually, the forms have an austerity or minimal quality; some are accented with bits of decoration or details of manufacture. They are shallow bowls or dish shapes resting on bases, some vertical and uplifting, others low and horizontal. They are comparatively free of intense surface ornamentation. Their directness and clarity allow the viewer to focus (literally) on the pieces and read the broad, uninterrupted surfaces and structured bases. Bowls 1 and 2 have a mechanical or structural quality. Tubes, rod and elements that seem to be extracted from industry or the laboratory rise up, holding and passing through the bowl.

On the surface of both is a small pin of transparent, glowing red plastic. With their glowing red beacons and mechanical bases, they seem to be machines or apparatus in operation. These bowls might be a response to the petroleum industry concentrated in Hamlet's home state. Bowls 6 and 7 have a tall, uplifting, spartan quality; their classical stance is reminiscent of oil lanterns from some ancient rite or olympiad. However, simultaneously, their sleek surfaces and contemporary materials indicate that they are products of our time. Both pieces have a squiggly, wavelike element running vertically from base to bowl. One piece has a pendant attached to the bottom of its wave element, much like the pendulum of a clock. The other's squiggly element rises up, intersecting and reflecting across the underside of the bowl and reads as a wave or frequency of sound or light. These simple signs of time and energy, the classical stance and contemporary material all build conceptually, making the pieces symbols of the eternal or universal, ancient and current, the vessel's presence in all cultures.

Hamlet's choice of materials serves to illustrate the previously described concerns. The bowl or dish-shaped elements are found objects, originally safety-valve membranes used in industrial plumbing and pressure systems. Made of the alloy Hastelloy (copper, nickel and chrome), they were retrieved from the scrapyard, refurbished and applied. They are ideal materials for her pieces, not only in the terms of form, surface and ease of use, but also conceptually—as industrial elements they add credence to her scientific and industrial interest. Their highly polished, hard surfaces concentrate and reflect light. If one holds hand or face directly over the bowl the reflected light warms the skin by radiant heat. Physically, this supports the visual reference to energy. The bases are constructed of off-the-shelf rod and tubing. The bowls are not attached but simply rest on the base. This juncture is made by using a rubber doughnut shape between the base and bowl, a cushioned and fractioned fit. The use of standard stick and readymades and the ease of construction cleverly fulfill another end: the work can be sold at a reasonable price, enticing the audience to not only enjoy, but also to start to collect holloware.

Hamlet's palette and esthetic blend art, science and industry, promulgating the idea that these disciplines can benefit one another and that the activity of the scientist or inventor is much like that of the artist. While the scientist's experiments are only physical steps to a greater find, so Hamlet's calculated, almost scientific use of material, technique and design give us pieces which are not only esthetically pleasing, but also speak of the maker's relation to art and industry and, possibly, her art's place in time.

Susan Hamlet's work was exhibited at the Helen Drutt Gallery during May, 1985.

Karl Bungerz is an instructor in the metals program at Moore College of Art in Philadelphia, PA. He also maintains his own studio, making jewelry, furniture and containers, as well as consulting on product development for industry.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.