Architectural Portraits of Vicki Ambery-Smith

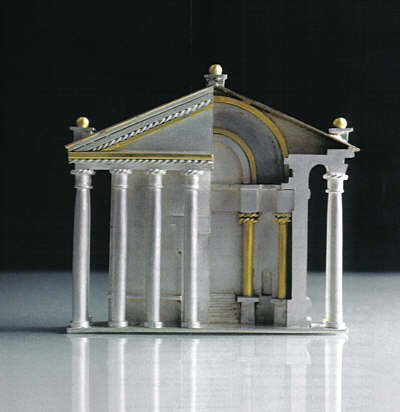

For nearly 30 years, Ambery-Smith has been using architecture as an inspiration for her work. Her name has become synonymous with finely wrought precious metal jewelry, boxes, and condiment sets whose inspiration lies in Renaissance, Palladian, and classical architectural precedents: a pendant based on the fifteenth-century Florentine architect Brunelleschis lantern, for example, or the Temple of Jupiter brooch, an exercise in pure classicism. Her work is represented in galleries, museums, and private collections in Europe, the United States, and around the world.

14 Minute Read

In London in the late 1670s, with the enthusiastic support of King Charles II, a large stone gateway embellished with sculptures of British monarchs was built on Fleet Street as a ceremonial entrance to the City of London. Known as Temple Bar, it was attributed to the architect Sir Christopher Wren.

In 1878, it was sold for £1 and removed from its City location and installed as the entrance to a country park. In November 2004, it is to be re-located stone by stone nearby its original location. To commemorate this historic occasion the British jeweler and silversmith Vicki Ambery-Smith has designed and fabricated a brooch in silver based on the monument.

For nearly 30 years, Ambery-Smith has been using architecture as an inspiration for her work. Her name has become synonymous with finely wrought precious metal jewelry, boxes, and condiment sets whose inspiration lies in Renaissance, Palladian, and classical architectural precedents: a pendant based on the fifteenth-century Florentine architect Brunelleschi's lantern, for example, or the Temple of Jupiter brooch, an exercise in pure classicism. Her work is represented in galleries, museums, and private collections in Europe, the United States, and around the world.

Although architecture has proved to be a matrix for her creative life, she has never considered it seriously as a profession for herself. On the contrary, as a child she was more interested in theater design. Never having studied architecture, Ambery-Smith feels her understanding of the subject has always been an "observational" one, and that it has changed significantly since she first started making architectural jewelry. She knows more now "just from dwelling in it."

From childhood, Ambery-Smith was always a maker rather than a painter and her inate three-dimensional conception of things extended to her drawings. She made Elizabethan costumes for her Barbie dolls and at 16 carved a chess set from a broom handle. Her actual introduction to jewelry-making was rather unconventional. Her first tutor was her dentist father, who, with his dental tools and the gold he had for his work, enjoyed making jewelry for his wife. He passed that pleasure on to his daughter, whom he instructed in the rudiments of the art.

At the age of 20, while in Germany on a college exchange at the Schwäbisch Gmünd Fachnochscule, Ambery-Smith visited Salzburg, and her interest in architecture was aroused by the buildings there, especially eighteenth-century ones. She explored the city, studying and drawing the buildings and extracting designs. The Baroque Holy Trinity church, with its onion-shaped dome that dominates the city's skyline, had a particular impact on her. She had grown up in Oxford, "the city of dreaming spires," and feels that this may have had a subliminal rather than a conscious effect on her. Salzburg brought this to completion. Her time there in 1975, and her exposure to the Andrea Palladio exhibition in London that same year, proved to be a turning point, and marked the beginning of her creative relationship with architecture.

By 1975, Ambery-Smith had already completed a foundation course at the Oxford Polytechnic and was in the penultimate year of her jewelry design course at the Hornsey College of Art in Middlesex. Its graduates were some of the most innovative jewelers of her generation and the college became known for nurturing its students' individuality.

On her return from Germany, her tutors were at first unimpressed and suspicious about her ideas and assumed that she was simply recreating a German jeweler's work. After graduating, she spent four days a week in a factory making charms, bracelets, and sovereign rings, and gaining some practical experience of commercial restraints and production techniques.

In her free time, she produced her own work on a workbench she set up in her bedroom, somehow managing to scrape enough money together to buy the precious metals she needed. Within a year, she had built up a sufficient collection of pieces to present to her prospective audience. Once seen there was an immediate and positive reaction to her work, with commissions and invitations to exhibit. Then a great step forward came in 1977 when the British Crafts Council sponsored a tiny studio for her and she was able to devote herself full-time to making her own jewelry. Her first show in that year was largely inspired by the Oxford buildings of her childhood and from that point on she never really looked back, as her crowded curriculum vitae attests.

The influence of architecture on Ambery-Smith's designs is profound, but it imposes its own constraints. Jewelry functions, after all, as an adornment of the human form. As such it is a miniature art, conceived primarily in two dimensions, and any piece of jewelry must be designed to lie comfortably across or depend from the body and work with it as it moves.

Three-dimensional, architectural structures must therefore be transmuted to fit these criteria, and pared down to a near lilliputian scale. As AmberySmith melds the disciplines of architectural design and practical jewelry construction, she must deal with the salient problems arising from the drastic reduction in scale of the given building, while maintaining its balance, proportion, and aesthetic. But she strongly disagrees with those who see her work as miniaturization per se.

To her it is portraiture, an interpretation based on a subjective view, and in some cases an evocation of a building, rather than a literal model. "For my architectural designs I rely upon pure observation to play with deception in perspective and proportion. Reducing a building on an exact scale would be mere miniaturization; I want to go beyond straightforward representation to a more personal interpretation of the character of the building." [1]

It is a disappointment to her that she finds that the work of some of her favorite architects, among them Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Anton Gaudi, does not readily transfer to jewelry. Various conceptual problems and complications are associated with reducing their buildings down to her scale and removing them from their natural context, and she fears that this process would inevitably deprive the buildings of their "essence."

The scaling down of buildings is of course a crucial problem that Ambery-Smith must constantly address. Perhaps, in the words of Professor David Watkins of the Royal College of Art London, her work is simply "architectural forms modeled into jewelry" [2] and for this there are distinguished precedents in jewelry history. Ambery-Smith constructs silver earrings in the form of Gothic windows, for example, where a medieval jeweler would use a similar means to frame the Virgin or a Crucifixion on a pendant, and his Renaissance counterpart would create a contemporary architectural framework in which to enclose classical figures. [3] She feels able, as these earlier jewelers did, to borrow freely from an architectural whole for her own use, be it a section of a house facade, a rooftop, or a gazebo, to form pendants, stick pins, and cufflinks.

Similarly, substantial silver rings are surmounted by gold Russian onion domes and moorish towers pierced with windows. One, topped with a tightly composed village comprising bridge, tower, rooftops and a flight of steps, echoes sixteenth-century Jewish marriage rings with a temple or synagogue placed four-square on their bezels. [4] Architect John Rae was reminded of Ambery-Smith's work when studying the silver reredos in the Opera del Duomo in Florence, where the silver had been modeled into representations of architecture.

He also noted the formal problems of adapting architectural structures to jewelry, given that architecture exists as an enclosure as well as an outward form. [5] Ambery-Smith approaches this challenge by implying the inner space through windows and door openings; by using the architectural methods of plan, section, and elevation; and by partly cutting away the frontal wall, thus creating an actual inner space within a structure of walls, floors, columns, and staircases with space flowing through them.

This technique has been particularly successful in the larger pieces of complex construction, such as the Globe Theatre brooch which has attracted so much attention. It had been the dream of the late American actor Sam Wanamaker to reconstruct the Elizabethan Globe Theatre, Shakespeare's London playhouse, on its original site on the south bank of the Thames. By the 1980s, plans were well under way, and Wanamaker, impressed by AmberySmith's work, approached her with the proposal that she make a silver and gold model of the original Globe.

This developed into a lengthy process as they worked together on successive versions as the plans for the building changed; these prototype "mistakes" are now highly prized and much sought after. The final version showed three-quarters of the "wooden 0" cut away to reveal the interior, with a partial view of both stage and seating. Eight brooches based on the model were produced for especially generous donors to the projected theatre, each one individually made and with slight variations. Prince Philip, Patron of the Shakespeare Globe Trust, was presented with a model of the theatre at the 1985 ground-breaking ceremony when the first oak beam was put in place by the American magnate Armand Hammer, who had pledged considerable sums of money to the project and had encouraged others to follow suit.

Most of Ambery-Smith's work, like the Globe, is commissioned, and she is pleased to count architects amongst the collectors and admirers of her work. They often have their buildings recreated as a piece of her jewelry for their wives.

Working on commission sometimes leads her into areas she has not previously considered. A recent request for cufflinks to be based on a house inspired by ancient Egyptian tomb decoration opened up for her a previously unexplored world of Egyptian art. In all commissioned work it is critical that the original brief is clear and workable and that any practical purpose is defined.There must also be freedom for the artist to interpret as appropriate.

On one occasion for example, in order to standardize the height of salt and pepper pots based on two different Venetian houses, it was necessary to adjust the proportions of one of them. For this commission Ambery-Smith worked, as she frequently does, from photographs supplied by her client. For another, who had lost a much-loved north London. The artist's movements as she works are swift and sure, and her working life is impeccably well-organized — she works during the hours that her two children are at school and confesses to a fastidiousness about her work, which is both essential and exclusive to it.

Seldom without a sketchbook and camera, she searches for ideas wherever she is, from travels abroad to walks in her own neighborhood — from French and Tuscan medieval villages and American and Russian cities to Edwardian houses in London. Her drawings, which are finely finished with color washes, are precise and carefully made and are becoming collectable.

Like many makers, Ambery-Smith learns new manufacturing processes as the occasion demands. Her production techniques are laborious and time-consuming. When making a free-standing object such as a box or a pepper pot, she starts with a drawing, followed by a card model, to ensure that the shape is accurate and feasible. To achieve this, she sometimes has to adapt the design of the original, not to say cheat a little, to make an object that will be stable. In the making, her jewelry and objects tend to share the same general techniques.

The basic forms and outline are traced over the image — drawing or photograph — and are then transposed onto a clear acetate film and from that photo-etched onto a sheet of silver, which is then scored, cut, and folded. Pieces are then assembled by silver soldering using a traditional mouth torch, although components of the larger pieces are sometimes riveted. The employment of a laser would expedite the photo-etching process because in theory one could carve the silver surface by laser at three or four different depths simultaneously.

Ambery-Smith, however, continues to employ the lengthier process of classic photo-etching since the laser process is more successful with brass, copper or bronze than with silver. Once she has done the artwork for the photo- etching she can then adapt and reduce a brooch, for instance, on a photocopier to a smaller version for cuff links, pins, and earrings. Thus, from the same drawing a number of pieces of jewelry can be made from one sheet of silver. She is not interested in computer-aided design — its machine — perfect precision would look wrong with her work. She prefers to work like traditional craftsmen and believes that the resulting imperfections and variations make each piece unique. And, like traditional craftsmen, she generally has an assistant and she enjoys the one-to-one teaching that involves.

The majority of her work is one-off, but she does produce some very limited editions. Most of the processes, including casting and repoussé, are undertaken in her own well-equipped workshop, although she has to send out specialist work such as engraving, enameling, gilding, and gem-setting. Her basic material is silver with red or yellow gold for highlighting architectural details and roofs, domes, banners, and pennants. For the latter she sometimes uses the less traditional metals titanium and niobium, activating their color-rich properties by means of electronic anodizing.

Ambery-Smith's most frequent silversmithing commissions are for boxes of various sizes and condiment sets. The boxes are usually imaginative creations based on towers and domes but with no particular building in mind. To celebrate the births of her children, Ambery-Smith made smaller, pillbox sized boxes, which were later used as receptacles for their baby teeth.

Ambery-Smith received her first liturgical commission in 1988: a Sacrament box to contain the sacred bread for the 500-year-old St. George's Chapel, Windsor. Based on the castle's Octagonal Tower, it was a parting gift from the Surveyor of the Fabric of the Building and resides in a side chapel serving the 700-member community of the castle, one of the royal residences.

Energetic, dedicated, and always alert to new ideas and challenges, Ambery-Smith admits she is now more interested in contemporary and future architecture. She has been looking at twentieth-and twenty-first-century architecture since the early 1980s, when she produced her first modern pieces based on the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Liverpool and the Houston towers. She particularly admires Daniel Libeskind's work, responding to what she feels is a human and emotional connection in his buildings.

Her silver brooch based on Libeskind's controversial plan for "Them Spiral," the proposed extension to the Victoria and Albert Museum, was shown at an international exhibition at the museum this year. She is now working on another, based on his dazzling new building for London Metropolitan University in North London. It is worth noting that the bold forms of these buildings — organic, full of movement, and in a sense dissonant — are in direct opposition to the balance, harmony, and classicism that many have come to associate with Ambery-Smith's output.

Ambery-Smith is also very attracted to the Art Deco factories and buildings found around the outskirts of London, and has been asked by one of her collectors to make a brooch based on the Hoover building, the star of this group. Her open-minded approach to new departures is further confirmed by her recent adoption of the sleek abstractions and minimal shapes of modern bridges for brooch forms. The bridges have excited the interest of a quite different audience from her architectural one, and have brought a startlingly different, cooler, and more strictly linear profile to her work. They came about as a result of a client, an engineer and bridge enthusiast, suggesting she should be "thinking about bridges" — she was unable to resist the challenge.

She is eagerly anticipating forthcoming architectural projects in London such as the proposed "Shard of Light," a triangular building whose long tapering point reaches skyward. Meanwhile, she has been focusing on plans and sketches of a radical new building, known affectionately to Londoners as "The Gherkin," which rises amongst the towers above London's financial district. Commissioned to make a silver brooch based on this, British architect Norman Foster's newest building, it will be interesting to see by what means, in a piece of only 2 x 5/8 inches, she will approximate the glass surface honeycombed with diamond-shaped windows.

But this, she feels, is her way ahead.

Deirdre O'Day, a former curator of jewelry at the Victoria & Albert museum, is a writer on jewelry arid fine and decorative arts and a BBC researcher.

- John Rae, "Forging Links," Building Design 24 (April 1987): 24-25.

- David Watkins, Design Source Book: Jewellery (London: New Holland Publishers, 1999), 125.

- "Princely Magnificence," (exhibition catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1980), 126; see also figures 628A & 628B in

- Yvonne Hackenbroch, Renaissance Jewelry (Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club Ltd, 1979), 235.

- Ring: Enamelled gold with Hebrew inscription (Jewelry Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, London), museum no: 4100-1855.

- Rae, "Forging Links": 24-25.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.