The Art of Gold

'The Art of Gold,' curated by Michael Monroe, is the first major survey of contemporary American goldsmithing. The traveling exhibition was organized by the Society of North American Goldsmiths and toured by Exhibits USA. Comprising 79 works from 76 artists, the exhibition bas a preponderance of jewelry over objects and hollowware. Bruce Metcalf's excellent essay in the exhibition catalogue locates the studio jewelry in the major design movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most notably the Arts and Craft. Movement, as well as assessing the current state of American goldsmithing.

11 Minute Read

When Virgil wrote, "Auri sacra fames!" ("Cursed craving for gold!"), it's a good bet he wasn't thinking about creamy yellow metal that can be drawn to a fine wire or beaten to a flyaway sheet. From antiquity, gold has been freighted with mythology, with politics and economics, and not surprisingly with class, race, and gender.

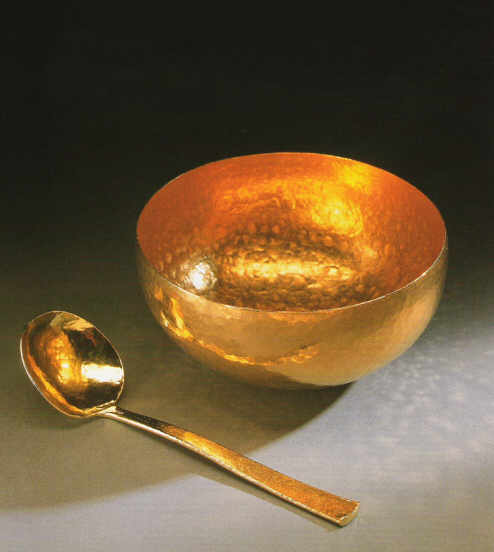

| Gary L. Noffke Bowl and Spoon, 1992-2000 24k gold, 20k gold bowl: 3 x 7 x 7″ spoon: 1 5/8 x 7 1/2 x 2 1/8″ |

Much of the writing about gold has focused on its value as currency and the lust it has engendered, from the treasures of Troy and Tutankhamun's tomb to the California gold rush. It goes without saying that this is not what attract, most goldsmiths. Gold is dense (one cubic foot weights half a ton) and soft (long ago Indian smiths so purified gold that it could be formed like putty around gemstones without damaging them); it is impervious to most solutions, and though it may be discolored and scratched during fabrication, it polishes up to a warm glow, in a range of muted tones from pink to green.

"The Art of Gold," curated by Michael Monroe, is the first major survey of contemporary American goldsmithing. The traveling exhibition was organized by the Society of North American Goldsmiths and toured by Exhibits USA. Comprising 79 works from 76 artists, the exhibition bas a preponderance of jewelry over objects and hollowware. Bruce Metcalf's excellent essay in the exhibition catalogue locates the studio jewelry in the major design movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most notably the Arts and Craft. Movement, as well as assessing the current state of American goldsmithing.

It's hard to think of a civilization that has not appreciated gold: Pharaonic Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent (site of modern day Iraq), tan Caucasus and Central Asia, Byzantium, West Africa, and, in the New World, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico. Gold and goldsmithing were well documented in Egyptian painting and in contemporaneous Biblical narratives. A, Moses direr is the building of the tabernacle, he notes that Bezalel "cast four rings of gold." He also notes that "they did beat the gold into thin plates, and cut it into threads," drawplates being unknown at the time (circa 4000 BCE). Granulation is believed to date to the fourth millennium BCE, or the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt, and was later perfected by the Etruscans in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. "[U]sing the method of colloidal fusion welding, powdered copper carbonate, probably pulverized malachite, was mixed with a bonding agent such as fish glue." Reintroduced in nineteenth-century Italy by Castellani, granules were still being applied with fish glue, although the results were said to be not quite as fine as those achieved by the Etruscans. Treasures found in the royal tombs of Ur (now Iraq) about third millennium BCE (around the time of Abraham) reveal chasing and repousse, engraving, or incising of beaten sheet, and what might be considered "protogranulation," along with chains and strung beads.

Like other art styles, goldsmithing has evolved over millennia through cultural contact via migration and trade routes, wars and conquests, even the capture of prisoners and slaves. Yet techniques and formal language have been remarkably persistent. Nature, for example, has been an ever-present theme. Egyptians represented grains of corn, pomegranates, and lotus blossoms; "bees sucking a drop of honey" adorn a Minoan amulet from the sixteenth century BCE, and 3,000 years later, insects were still being represented in Art Nouveau. Likewise, sources of inspiration in "The Art of Gold" range over much of recorded history, but there arc only a few references to modernism, postmodernism or even post-postmodernism. There are, however, some evocations of jewelry's history, from Egypt to the Victorian Age, along with a few commentaries on the field and one metalsmith's valentine to smithing.

| Kathy Buszkiewicz Omnia Vantis II, 2001 18k yellow gold, pearl, U.S. currency 1 x 1 x 1 1/4″ |

Several of the works included were inspired by earlier art movements. Linda MacNeil's Lotus necklace commemorates classical Egyptian symmetry, while a bracelet by Myron Bikakis and Mark Johns recalls Hellenistic chainwork. Mary Preston's filigree brooch carries Victorian overtones and shows off the ductility of gold as seen in Asian filigree. Richard Mawdsley has built his own frieze (Bricks and Columns) out of densely packed tubing, in an apparent homage to the Greeks, from whom we have purloined so much visual language. Though Petra Class names her wirework pin after the jeweled garlands and ribbons popular during the reign of Marie Antoinette, the pin actually resembles a necklace in a fifteenth-century Flemish portrait of Maria Maddalena Baroncelli by Hans Memling.

The few pieces that showcase ancient techniques reveal the intrinsic satisfaction of handwork and its relation to technology. In Omnipotent Optimism Christopher Hentz has chosen three different colors (karats) to shove off the kind of guilloche engraving seen under enamel in Cartier's best works. Granulation continues to fascinate as a technique and an embellishment. Douglas Harling's intimate Sea Saw brooch is one excellent example, recalling Victorian scrollwork and the neo-classicism it represented, as well as Celtic knots and their reinterpretation in gold by commercial jewelry houses early in the twentieth century. But for bravura evocation, it's hard to beat Kent Raible's Pregnant Chalice. Faberge might be turning over in his grave, but Raible has gone the master's egg one better, reinterpreting the biblical symbol of fertility and the ornate objects produced for acquisitive royalty in the last century, Although tastefully restrained, it's a jaw-dropping confection with gemstones, granulation, and complex fabrication.

Nature themes do seem impervious to the passage of time. John Iverson has long used Industrial Age electroforming to preserve leaf forms, and his giant spiky Sycamore Pin is a simple and graceful specimen in 18k gold. Sue Amendolara's standing object Planting Roots typifies her botanical and maternal themes, executed in a classical metalsmithing style with clean lines, tapering sprouts, and sleek pod. Tom Herman's virtuoso carved bracelet d Tangle of Brambles, of shakudo and 18k gold, and Jim Kelso's intimate Chrysanthemum Lady Bug Brooch effectively use color in mixed metals with representational flora. Herman's hinged bracelet with diamond clasp suggests the ornamental foliage of fin-de-siecle and early twentieth-century Europe as seen in the Arts and Crafts movement, while Kelso's work recalls the inlaid metalwork in Japanese swords. Perhaps the most inventive use of nature belongs to Jennifer Trask, whose brooch Popillia Japonica appears at first to be a serene symmetrical composition of muscular cabochons in an oval frame, arranged like carved gemstones in a Victorian brooch, themselves copies of Castellani's early nineteenth-century copies of Etruscan granulation and beading. Closer inspection reveals the cabochons to be the bodies of Japanese beetles, lending a new twist to mimicry in nature and elevating pestilence to art. The work also has a precedent in glass beetles made by Tiffany in the early twentieth century. In addition, it's one of the few examples of mixed media in the exhibition, representing the conflation of high and low that has characterized much jewelry making since the 1970s.

| Richard Mawdsley Bricks and Columns, 1992 18k gold, lapis lazuli 2 3/8 x 3 1/8 x 3/8″ Courtesy Mobilia Gallery |

By the nineteenth century the arts, and jewelry, began to comment on themselves and to look back to gothic, neoclassical, rococo, and Renaissance styles. The twentieth century added Modernism, from which "art jewelry" evolved. Following the postwar generation came those who embraced the Modernist aesthetic (Thomas Gentille) as well as those who eschewed it (J. Fred Woell A simple forged neckpiece by the late Ronald Hayes Pearson recalls those beginnings. Made only four years before Pearson's death in 1996, it reveals the consistency of his aesthetic. Modernism lives on in the constructivism of Abrasha, represented here by a ring with rolling gemstone, and in the cool geometry of Donald Friedlich's brooches, here enlivened by his experiments with dichroic glass. Friedlich's designs are connected to minimalist sculpture more than to the human body; one imagines them blown up to wall size, with light and color playing on a larger field.

| Thomas Herman, A Tangle of Brambles, 2002 18k gold, shakudo, diamond length 7 7/16 x 15/16 x 1/8″ |

By contrast, Lisa Gralnick constructs intimate architectonic forms that retain the maker's touch. Gralnick's explorations into physics and structure have morphed into origami, treating the metal as if it were paper and creating a light but stable structure with a soft handworked finish. Gralnick appears once again to have embraced beauty, leaving behind the dark narratives of the past decade, while abandoning neither the thoughtful underpinnings of her material choices nor her enviable craftsmanship. Bruce Metcalf has likewise turned to lighter (but never lite) subject matter with Two Dotes in a Private Garden, a smorgasbord of materials and techniques, and one of the few openly narrative pieces in the show.. Lacking the prickliness of some of Metcalf's figures, it shows a love of making, while thinking about Victorian jewelry, nature, and the body.

| Douglas Hailing Sea Saw, 1999 22k gold, 14k gold, pin mechanism, freshwater pearls 1 3/8 x 2 1/4 x 1/2″ |

They are, if you will, messengers of postmodernism, in that the extra-visual narrative, or implied content, is more important than the formal structure. Susan Kingsley's Priceless Charm Bracelet is a good example. Like a conventional charm bracelet, it is a short chain hung with multiple charms. But the joke is that the charms are all shaped like jewelry price tags, with no prices listed. The "backstory" is as significant as the object, since the homogeneous shapes of the charms provide little variety on their own. On the other hand, Kathy Buszkiewicz is right on target with her continued exploration of values and our throwaway culture: she uses discarded U.S. currency as a graphic found object with a past. At first glance, the pattern of green and white resembles a marine animal more than the detritus of capitalism, as overlapping shards are assembled into a giant stone atop one ring. Buszkiewicz inadvertently honors the engravers whose skill makes the money graphic in the first place. Louis Mueller's witty gold picture hooks tweak the fired question of whether craft is art. Why not just hang the whole body, on the wall, or bring the "real" art (i.e. paintings) to the body?

And finally, the valentine: Gary Noffke's bowl and spoon. A massive amount of gold has been raised to create a place setting of primitive implements, what might be unearthed at the site of a Cro-Magnon picnic. These objects completely inhabit their "vesselness" and their function, and Noffke directly honors goldsmithing by retaining the visible planishing marks and untrimmed edge. The pieces celebrate the sense of touch as well as sight in the golden glow that accompanies what is surely their substantial weight. In these simple implements, Noffke has married history and materiality, and with it craft's traditional connection to function. They are all about process and all about the beginning of beauty.

In an ideal world, what should we wish for in a survey of American gold? The United States is used to being the new kid, and its art has often functioned as a kind of cultural sponge, absorbing elements from disparate sources. That kind of greedy energy is missing, perhaps because gold seems so serious. This collection contains little that is radical, too few pieces that are thought-provoking, and a few that would be of little interest but for the gold. Make no mistake: there is some really beautiful jewelry and some first-class craftsmanship, including that of relative new comer Namu Cho, whose Damascene pin unites the graphic patterns of Japanese prints with the skilled hands of the engraver. But the exhibition could use a spark, such as the irreverence that Hermann Junger, Reinhold Roiling, and the succeeding generations of German students brought to postwar treatment of gold. Missing is the tenderness of a Mario Phnom the wantonness of a Karl Fritsch, the eroticism of a Pat Flynn, or the material voluptuousness of a Giovanni Corvaja.

| Ronald Hayes Pearson Torque 18-142,1993 14k yellow gold, amethyst 7 7/8 x 4 7/8 x 15/16" Courtesy Carolyn A. Hecker |

Five years ago, Bettina Schoenfelder stated that, for jewelry, "the period of spectacular rebellion is over." Maybe it is, and maybe we do need to look to "an abundance of contextual data fields which provide the material for the stories that constitute jewelry." For context, go back to "10 Goldsmiths," an exhibition at the Rezac Gallery in 1988. Two artists were American, and only one, Harold O'Connor, is in this current show. In the accompanying catalogue, Ian Wardropper, Associate Curator of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, observed of the artists included: "Some are interested in breaking boundaries between art forms and allowing jewelry a voice in the expanded dialogue between the arts. Some walk a fine line between making costly objects and spoofing that activity, questioning the nature of material possessions. Some are more interested in contemporary design and the relation of their work to current fashion," Such a range serves the field well. It would be an understatement to say that a survey of American goldsmithing is overdue, and even Michael Monroe would agree that "The Art of Gold" is the first word on the subject, not the last.

| Kent Raible Pregnant Chalice, 2002 18k yellow gold, 18k white gold, 18k pink gold, fine silver, sterling silver, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, chysacolla, opals 7 5/8 x 4 1/4 x 4 1/4 " |

The estimable Hermann Junger described his coming of age in Hanau, Germany, "the Town of Noble Jewellery," in which a state school of jewelry had existed for 250 years. "For me, a goldsmith was one who above all draws or sculpts; goldsmithing was only another word for "art". It did not dawn on me that this activity starts First of all with craft."' Thanks to the many teachers who set the standards, we now know this too. But go see for yourself. "The Art of Gold" will be traveling around the country for the next two years. The twenty-first century could be time for the next American gold rush.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.