The Once and Future Sapphire

7 Minute Read

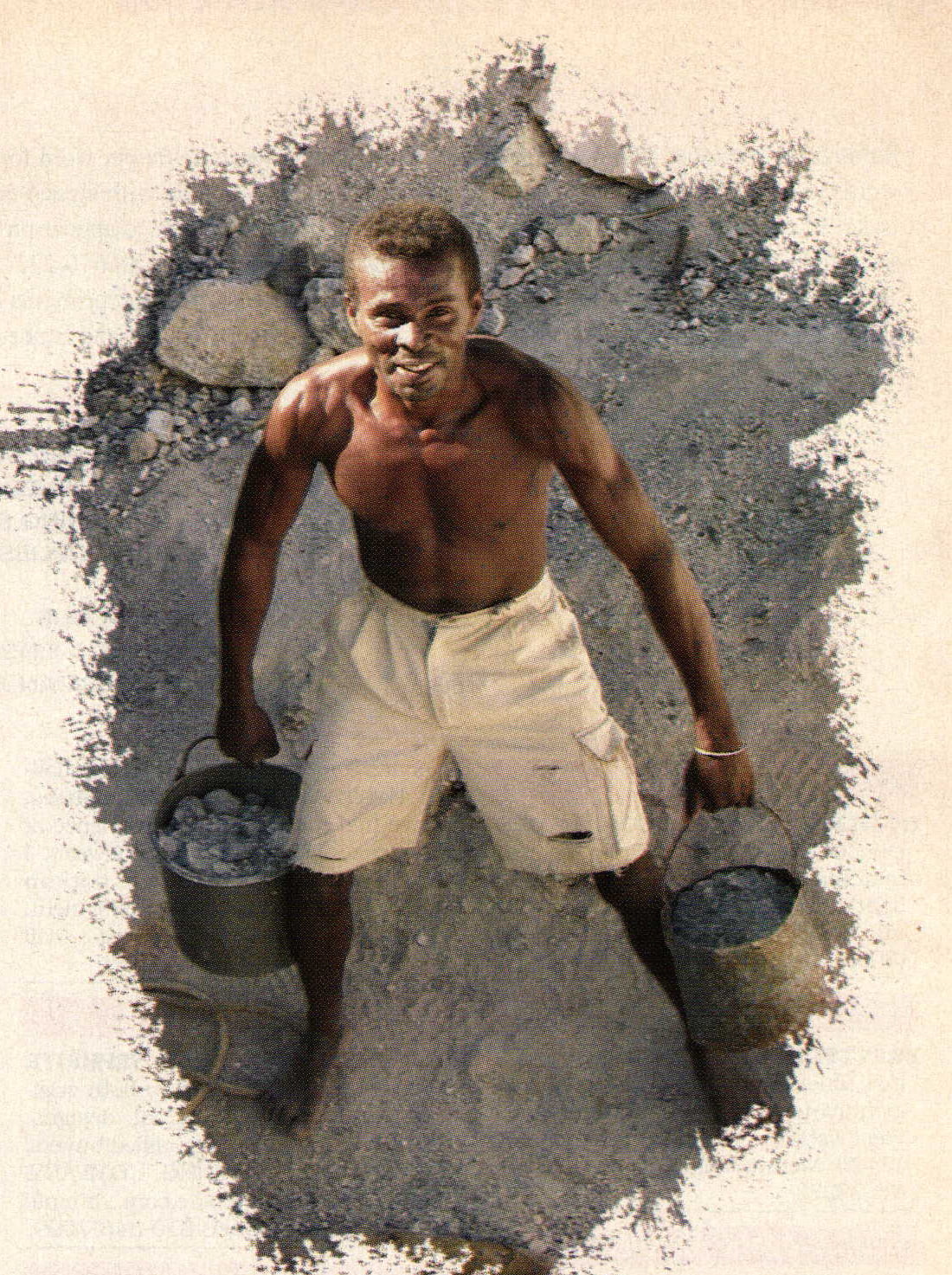

Andranondambo countryside, southern Madagascar, 1994

Imagine a gently hilled plain, covered with a beautiful baobab forest, surrounded by an arc of mountains under a pure blue sky. There, a young zebu cattle keeper is watching his animals. Time passes slowly in southern Madagascar. The French colonials that once mined mica and uranium are gone. Gaston, the young zebu keeper, remembers them as shadows from childhood tales. His mind is focused on his zebus, and the blue sky that surrounds him. Then, on the ground, a blue flash attracts his attention. He picks it up and studies it. He scans the ground and finds several more. A few days later, he calls on one of the French expatriates still living in the area. He is told that the blue stones are sapphire.

Gaston, the former zebu keeper, told us the story of his discovery in June 2005. With my two assistants. I was scouting Madagascar ruby and sapphire mining areas for a joint venture of the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences (AIGS) and the Gübelin Gem Lab. We were lucky to spend two days talking with Gaston about the discovery, gems, and his life.

The place where Gaston discovered his sapphires has changed after 10 years of mining: The dark, shady baobab forest is now mostly gone, and pits and tunnels are scattered about the hard, white rock. The area is still very beautiful, and now an Australian company called the Societe d'Investissement Australien a Madagascar (SIAM) is starting an important mechanized mining project.

If Gaston did not become as rich as the big Ilakaka dealers, he is no longer a poor zebu keeper. Gaston told us that since its discovery in 1994, his mine has produced more than 20 kilograms of the precious blue gems. Of course, not all have been top quality, but Andranondambo is known to have produced sapphires equal in beauty to the best of Myanmar (formerly Burma). Kashmir, or Sri Lanka. Now, with his 120 zebus, two wives, and 12 children, he is one of the wealthiest people in Andranondambo, and he was a wonderful guide during our two-day visit to his village.

But Gaston's discovery might have come to nothing if it weren't for Antsirabe, a city in central Madagascar, which before the Ilakaka sapphire discovery was the country's main gem business center. Thanks to its tourmalines and wide variety of other gem mines, people from Antsirabe are the most gem-savvy people in Madagascar. The city boasts a permanent gem market, and most of the experienced gem miners working in Ilakaka are former Antsirabe miners. This explains also why Madagascar tourrnaline is getting rarer: The sapphire business in Ilakaka is just more financially interesting than tourmaline mining around Antsirabe.

We were told that many of the local dealers belong to the important Malagasy-Chinese community. These people have many business interests, from import-export to restaurants and hotels. One day, one of these dealers got some stones from a relative living in Fort Dauphin near the now-famous Manjanary emerald mines. This dealer showed the stones to a visiting Thai-Chinese dealer on a tourmaline buying trip. The Thai dealer immediately recognized the stone as a gem-quality sapphire. Soon, several Thai sapphire dealers came to Madagascar and traveled south to Andranondambo. That was the starting point of the modern Thai interest in Madagascar.

In fact, sapphires have been known to exist in Andranondambo for decades. During the colonial period, geologists like Lacroix (1920s) and Besairie (1960s) explored Madagascar and reported most of the ruby and sapphire occurrences that are known — other than the Ilakaka deposit, which was only discovered recently. However, there were no buyers, and thus no motivation for people to start digging for gems.

In the 1990s, sapphire dealers in Chanthaburi, Thailand, faced a crisis: The mines in Chanthaburi, as well as nearby Kanchanaburi, Thailand, and Pailin, Cambodia, were nearing the end of their useful life. Thai dealers began traveling to East Africa to buy the ruby mined near Tsavo National Park in Kenya: Morogoro, in the central part of Tanzania; and then sapphires in Tunduru, in southern Tanzania, after the discovery of sapphire and chrysoberyl there in 1992.

Reports of viable sapphire deposits in Andranondambo in 1994 brought the Thai dealers running to the island. A second sapphire deposit was discovered at the extreme opposite end of the island, a few miles away from the beautiful and scenic Diego Suarez bay in the north. Then, two years later, sapphire was found in the north again in an area called Ambondromifehy. This latter deposit was alluvial, which makes mining the gems easy, but the stones were formed in basaltic rock, so they tended to be dark and/or greenish in color, limiting the interest. Even so, there are still a few hundred local people currently at work mining in the Ambondromifehy area.

The discovery of Vatomandry and Andilamena deposits in 2000 (see "Ruby Boomtown" in the January/February 2006 issue) was also important. Several thousand miners who started at mines in Andranondambo or Ilakaka moved to the new area. Werner Spaltenstein, a well-known Swiss gem dealer, says that Vatomandry ruby material did not react well to heat treatment compared to Andilamena stones. That might be the reason why most of the miners moved to Andilamena, as the stones there were easier to market.

The discovery of these deposits — coupled with the major alluvial deposit of metamorphic blue, yellow, and pink sapphires in Ilakaka in 1998 — suddenly boosted Madagascar as the worldwide main sapphire producer. Dealers rushed to Madagascar, leaving their former suppliers in Australia, Sri Lanka, and the newly-promoted Tanzania with no market for their gems.

It was the right time for Thailand. The international center of the ruby and sapphire trade had just been hit by the 1997 Asian crisis and the concomitant drop in value of the baht. Suddenly, the traditional supply of Australian sapphires became too expensive for Thai dealers, who were fighting for survival against strong Sri Lankan competitors who were slowly mastering the secrets of heat treatment.

Sri Lankan buyers are now commonplace in Madagascar, and also in Tanzania. I even had the impression, traveling from Ilakaka to Sakaraha and passing by Manombe, that there were more Sri Lankans than Thais. Sri Lankan burners have surpassed their Thai competitors in heat treating blue sapphire. Ilakaka and Tunduru stones are geologically very similar to the sapphires of Sri Lanka, so the Sri Lankan dealers have found in Tanzania and then in Madagascar a good solution to their own local supply difficulties. Buyers in Colombo or Ratnapura in Sri Lanka, or Bangkok or Chanthaburi in Thailand, are likely to buy "Ceylon sapphire" which was in fact mined in either Madagascar or Tanzania.

Even with these new discoveries, Madagascar still has incredible untapped potential: Geologically speaking, more than 80 percent of the island could hold ruby and sapphire deposits. In less than 10 years, six ruby and sapphire deposits of different types have been discovered, but there is more to come. Madagascar has twice the gem-producing area of Myanmar and Sri Lanka added together: If the famous Mogok area in Myanmar or the Ratnapura area in Sri Lanka are a total of 50 km by 50 km (31 miles by 31 miles), Ilakaka is more than 300 km by 300 km (186 miles by 186 miles). And after only six years of production, Ilakaka is far from fully exploited. The potential in the jungle-covered areas of Vatomandry and Andilamena looks similarly enormous. There are new reports of alluvial rubies and sapphires being found in the deep, rain forest-covered mountains east of Andilamena up to Fenoarivo. Other potential mining areas exist east of the Fianarantsoa corundum deposits, and are also known in the south near Bekily, Ejeda, Betroka, and Ikongo; in the north near Andapa, Ambilobe, and even in the tourist paradise island of Nosy Be, where attractive purple sapphires have been found.

During my 60 days exploring Madagascar in the summer of 2005, I began to fully appreciate the island's potential. The best stones from Madagascar — its rubies and pink, blue, yellow, and padparadscha sapphires — can compete in beauty with the best stones from Myanmar, Kashmir, Thailand, Cambodia, or Sri Lanka. For gemologists, this creates a challenge. Gems from new areas are arriving in the market much faster than the gemological studies needed to reliably identify them can be finished. As of today, the science is incomplete.

The author would like to thank Jean Baptise Senoble, Henry Ho, Richard Hughes, and the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences and the Gübelin Gem Lab for sponsoring his trips to Madagascar. His gratitude goes to all the wonderful people he met in Madagascar, including very special thank-yous to Gaston in Andranondambo, the man who picked his pocket in Ilaknka, and the rats in Andilamena. Last but not least, a very special thanks to Richard Wise for his painstaking editing and translation.

by Vincent Pardieu with Richard W. Wise

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.