William Underhill: Organic Geometry

10 Minute Read

William Underhill came to bronze pots just as his teacher at the University of California at Berkeley Peter Voulkos was leaving clay ones. After a decade of stacking, slashing and cantilevering pots—attempting to stretch their skins into more evocative sculptural forms — Voulkos had tired of the confined esthetic. So, in 1961, he helped establish a small foundry at Berkeley where he began casting sculptural forms in bronze.

William Underhill was one of the few artists who used the foundry to make pots. The process was plain. He would throw a thick-walled clay vessel on the potter's wheel, model its interior surface, then coat it with wax and cast that wax shell in bronze. This method, in effect, turned the clay pot inside out. Indentations and incisions in clay appeared in relief on the surface of bronze. The results were highly embellished, almost ritualistic, textures on organic forms. In the 1962 "Young Americans" exhibition of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts,

William Underhill was awarded the Bronze Medal for a form that looked like an exploding mailbox—all tattered planes and segments of spheres. This was one of the last to follow the Voulkos lead of taking vessels apart at the seams. For in 1963, he came up with two configurations that have occupied him right up to the present.

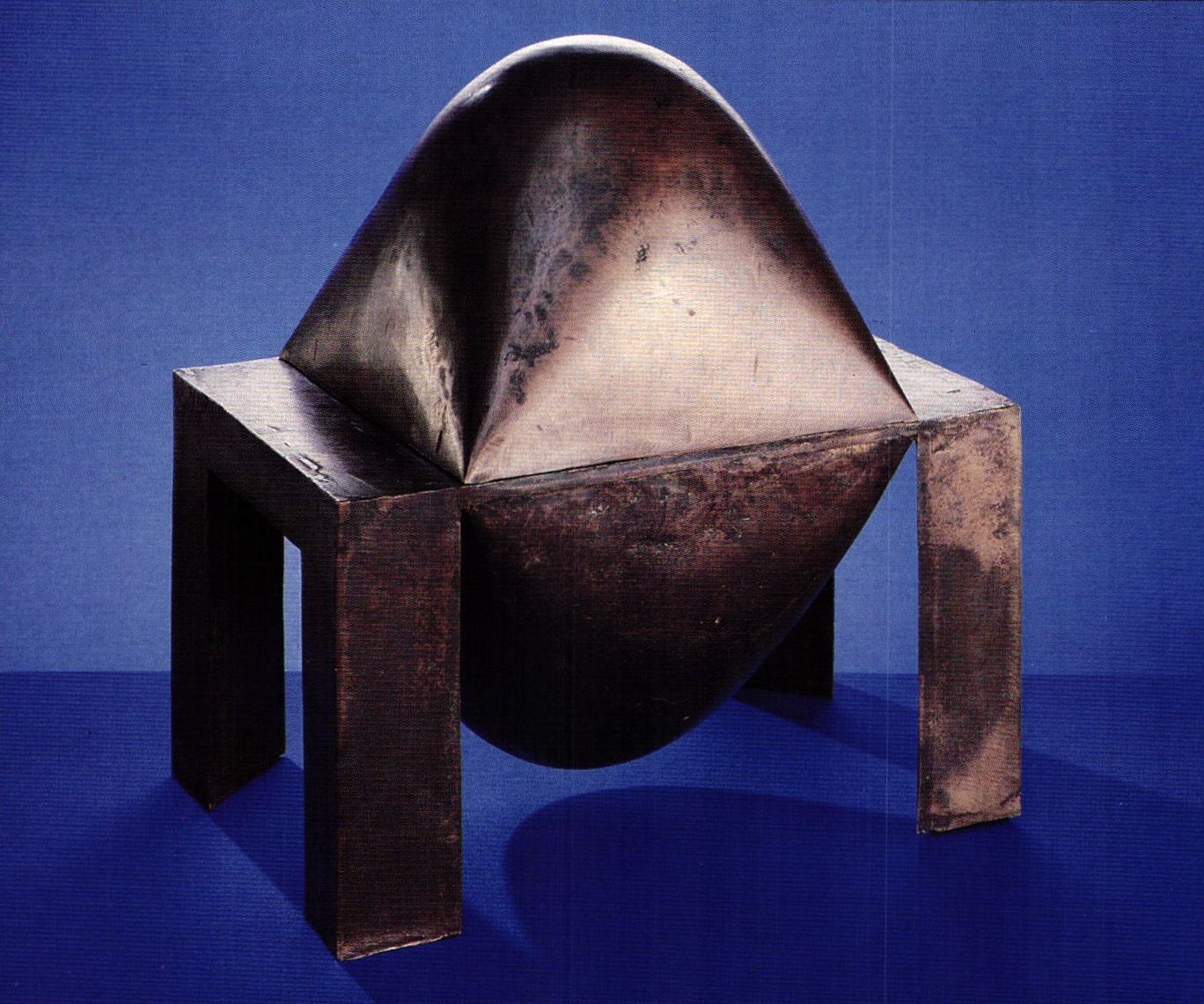

One, Flared Vessel, perches like a tornado on a gumdrop-shaped base. The other, Lidded Vessel, looks like an egg suspended between four posts. The primary attraction of both is their curious transition of shapes. That transition is dramatic where the stem of the flared vessel connects to its domed base, but clumsier where the planar legs of the lidded pot abut their volumetric core. The legs clearly support the lidded form, but their broader visual purpose is less apparent. As a whole, the elements of these forms lack a unifying visual logic.

Throughout his early works, William Underhill experimented with different configurations of legs and bases, but they invariably assumed the role of physical conveniences—small platforms or plinths raising the bellies or stems of vessels a few inches in the air. William Underhill easily could have solved the problem by making flat-bottomed pots, but he gravitated toward images that raised this question of form and structure. He seemed to be searching for ways to merge the two, and thus heighten the sensual impact of the organic shapes that attracted him.

Despite these apparent weaknesses, however, these early forms contain the seeds of the compelling organic geometry that emerged later. For they manifest few pure shapes. Spheres are always slightly Parabolic—as though stretched by some hidden pressure. And the walls of the flared vessels don't graduate evenly. Their bulges and spirals convey the impression of viable growth. One senses that their surfaces contain the potential of living forms.

That sense developed even further when William Underhill turned from clay to wax originals. Transferring clay to wax had forced him to make the forms in negative and envision their eventual positive. Working directly in wax, Underhill was able to see the form as it would appear in bronze. The translation became one-to-one. It enabled him to work the interior and exterior surfaces simultaneously. That hadn't been the case with the clay originals - he had simply applied textures to the inner wall of the clay hollow. The forms often appeared to be little more than vehicles for decoration. With the wax originals, the method William Underhill used to fabricate the image rose to the surface.

The areas he composed of sheets were smooth, as were the segments derived from molds. By contrast, hand-modeled portions conveyed a meticulous tactility. In the early flared vessels, William Underhill applied all of these techniques, gradually coming to terms with their visual impact on form. Yet their conglomeration in a single image suggested a coopered appearance. Alternately placid and rumpled, these patchy surfaces encouraged the eye to stop and go, to sporadically skim the high spots for nuance or to stall completely where shapes converged. Polished areas crumbled into pocks and pittings, so one's eye tended to wander aimlessly.

Flared Vessel, 1971, changed all that. It was no longer a patchwork of techniques, but a form modeled piece by piece out of soft dollops of wax. More than simply giving the surface an "all-over" texture, this method infused the form with the simple identity of its means. The pot was pinched into shape. Its accretion of dabs acts as the external skeleton of its form—embodying both structure and shape. In that sense, its technique is its expression and that expression the sensual force of organic growth. No longer the self-contained twister of eight years before, it flares almost to the point where its rim begins to curl back upon itself. The dabs pace the eye across the delicate surface, sweeping inside and out. This steady, almost hypnotic, movement adheres the eye to the form, conveying the full experience of its volume.

As I mentioned before, this wasn't the case with previous forms. Their patchy surfaces tended to confine the eye to the transitions of shapes. Here the shapes don't merely converge, they interact, resisting yet appearing to generate one another. But this form didn't mark the end of the disparity between elements within Underhill's pots. Problems continued to crop up whenever he combined planar with organic forms. Occasionally, he would mount a flared vessel atop a tablelike base. Or, as in East Valley Pot, the 1973 version of the lidded vessel, he would join the egg with prismatic legs. But the transition was considerably less conspicuous than it had been previously.

For one thing, the entire surface was smooth. The egg no longer had to appear handmade. William Underhill's eye had turned to measuring proportions and developing the form through its taut surface. The shape is more pyramidal than bulbous—fertile rather than fat. And this subtle triangularity is echoed by the prismatic legs.

This geometry wasn't the cool study of the math books, it came from warm models in the flesh and fields. Sensual rather than analytie, anthropomorphic images such as Sliced Forms, 1981, nevertheless fell into an increasingly formal net. They came with few anecdotes and virtually no surface decoration. They were simply form, without all the intellectual sweat. William Underhill had resolved the disparity between base and form by infusing each with some of the visual character of the other.

The legs of Sliced Forms, for example, are mere planes. And more planes grin across the pared face of the central sphere. Together they speak the language and proportions of cross-sections while the belly of the crablike form conveys volume. Its roundness is parabolic, its fullness elastic. Yet this elasticity is contained by the exactitude of the arched planes that segment the form. We see its warm-bloodedness sealed or embodied by geometry. Instead of arousing the eye with complex, highly mobile surfaces, as the flared—"pinched"—vessels do, it offers complex configurations whose surfaces are no more than smooth geometric facets and membranes—a fusion of anthropomorphic and architectural form.

Those looking for connections with 20th-century art and architecture may want to refer to Brancusi, Arp, Giacometti or Louis Kahn, but William Underhill's esthetic is that of the vessel. His geometric meditations depend on the inner and outer surfaces of open forms. And the simpler the better.

The 1981 Moker Series of bowls were the first to successfully combine planar with pinched components. They comprised a basin pinched out of small medallions of wax perched on a cube. Like the flared vessel from 1971, the technique is the expression. In this instance, however, the expression is less allegorical. It isn't growing. The classical shape of the bowl turns faintly inward at the rim. The pressed medallions of wax persuasively detail the form. The form itself evinces a tactility that one's eye practically feels. This quality of the hand comes across so strongly because William Underhill treated the surface after the cast in a way that would reveal a sense of plasticity. The mossy bronze, sealed beneath a sheen of wax, appears moist, pliant, as though it could still be altered by the slightest touch.

This sense of malleability also appears at the junction of the cubic base and hemispheric bowl. The corners of the cube are peaked. Between them the top edges of the walls are slung parabolically, as though the bowl had simply shaped, even melted, its own nest out of the underlying block. These small details of accommodation not only permit the cube to serve quietly as a base, but they describe the efficient union of the two forms.

William Underhill has managed to carry that beautiful efficiency even further in his most recent pots. The result—as often occurs when art conveys maxi. mum effect by minimum means—is a degree of abstraction that overcomes the relative confines of the medium. In the pots Underhill made before the mid-70s, the forms invariably served the idea of the vessel.

In recent works, however, that balance has shifted. The vessels are at the convenience of William Underhill's ideas about form. The pots have become vehicles of geometric sensuality. They make virtually no distinction between the visual roles of their physical parts. Tops and bottoms act intrinsically as form. And in such works as Hips, 1983, and Kabuto, 1984, there is little doubt what kind. These pots are girls. The once spindly legs of the 1963 Lidded Vessel have evolved into fulsome thighs, the bulbous central egg into the sensual volume of a pelvic traingle. Hips is the more voluptuous of the two, yet its eroticism is tranquil, almost meditative. Its curves are gentler, softer, than the hardheaded distensions embodied by Kabuta, Japanese for helmet. At the same time, it is denser, more compact. The wider arch of its cannister lid doesn't force the eye into quick turns. Its seams, surfaces and edges constantly convey attention in easy sloping arcs downward toward the sensual junction of its belly and legs.

That concentrated geometric sensuality appears again in Willendorf, 1983. The bronze precedent for this pot may be the lobed ritual vessels from Chou Dynasty, China, but its inspiration is sea bubbles clustered as foam, or cells as zygotes. William Underhill owes its metabolic configuration to "the closest stacking of spheres"— nature's way of stabilizing round volumes in stacks. Here the balls overlap and merge into a tetrahedral arrangement whose structural efficiency appears to be the very essence of grace. Its rhythmic union of globes pulses the eye in short arcing beats over and around its surface. All those soft and easy undulations stop abruptly at the short planar neck that rises intractably from the inturned center of the cluster.

William Underhill didn't confine this compact geometric expression only to lidded forms. He also used it in such open vessels as Knife-Edge Pendentive, and Triangle Yantra, both 1984. Unlike the earlier "pinched" bowl on a cube, these exist as hollowed chunks, rather than stretched membranes. Expansiveness is replaced by weighted mass. Instead of reaching out and enveloping empty space, their austere proportions compress it into surfaces and intervals of dense form.

As with Hips or Kabuto, they compel the eye by their matter-of-fact anatomy, whose configurations are self-defining. For they express simply the physical requirements of their merged shapes. Pendentive reveals the transformation of a cube into a dome and then the accommodation of that inverted dome atop another cube. Yantra shows the extraction of a prismatic core from a hemisphere. The prism is both surface and hollow—a riddle that keeps the eye moving inside and out, constantly weighing, measuring and trying to figure the small difference.

The beauty of William Underhill's vessels is that their interlocking shapes flow together as though the very seams and transitions were arranged by some underlying structural order, one that nevertheless works from the surface inward. Its poetry is sensual, meditative, metered by the plain requirements of fitting form around hollows.

William Underhill teaches sculpture in the Division of Art and Design at New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University.

Ed Lebow writes occasionally about art.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.